NEW YEAR'S IN JAPAN

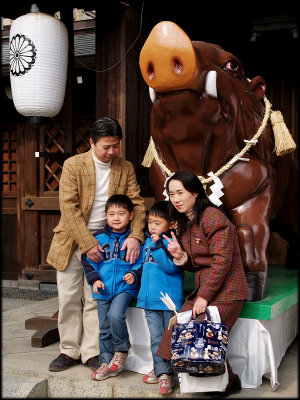

girls selling money rakes The biggest holiday of the year in Japan is New Year’s Day. Even though the Japanese celebrate the new year according to the Western solar calendar rather than the Chinese lunar calendar they still recognize Chinese astrological years such as the Year of the Pig or the Year of the Sheep. Posters and gifts with the new year's animal are everywhere. The Japanese used to mark New Year's Day at the same time as the Chinese but they changed the date to January 1st after World War II.

The New Year holidays, known as Shogatsu, have traditionally been a time for thanking the gods (“kami”) who oversee the harvests and for welcoming the ancestors’ spirits who protect families. The custom of displaying “kadomatsu” (decorations of pine branches and bamboo put up at both sides of the entrances to houses) and “shime-kazari” (straw rope decorations) was to welcome these gods and spirits. At the beginning of the year, people expressed appreciation to the gods and the ancestral spirits and prayed for a rich harvest in the new year. Because of this, the New Year’s holidays are for the Japanese people the most important of all annual celebrations. Many people at this time draw up plans and make new resolutions for the coming year. [Source: Web-Japan, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Japan]

The New Year season is a time when families get together and people return to their hometowns. People clean their houses to make them welcoming to friendly spirits. Women spend a lot of time in the kitchen preparing traditional foods or ordering them from a department store. There is a lot of television watching with some visits to shrines and temples sandwiched in.

New Years Day is essentially an agricultural festival. It reflects the desire for a good harvest and good fortune. New Year's Day ornaments include oranges, fern leaves, stacked rices cakes, a small lobster and “ kadomatsu” (pine branch decorations) put on gates, doors and the grills of cars. All of these things have special meanings and are placed on an altar as an offering to “toshigami”, the god of New Year.

“ Kagamimochi “ New Year cakes — three different-size mochi rice cakes placed on top of one another wedding cake style with decorations “are placed at the entrance of houses during the New Year season. Large ones weighing 500 kilograms are placed at some shrines.

New Year’s has traditionally been regarded as joyous yet somber time — in which one spoke quietly and respectfully greeted others’summed up by the expression “ Ichinen no kei was gantan ni ari”, meaning the way that one spent New Year was an indication of the way one would spend the rest of the year.

Good Websites and Sources: Good Photos at Japan-Photo Archive japan-photo.de ; Hub Pages (Good Site) /hubpages.com/hub ; Wikipedia article on Japanese New Year Wikipedia ; New Year’s Food hillslearning.wordpress.com ; Photos japan-photo.de

Links in this Website: JAPANESE CALENDAR AND DAYLIGHT SAVINGS TIME Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; HOLIDAYS IN JAPAN Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; NEW YEAR'S IN JAPAN Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; FESTIVALS IN JAPAN Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; FUNERALS IN JAPAN Factsanddetails.com/Japan

New Year's Parties in Japan

celebrating year of the pig “Nenmatsu” (the year’s end) and “nenshhi” (year’s beginning) is the traditional season of heavy drinking. It is not unusual for people to participate in numerous “bonenkai” (forget this year’ parties) in December, including work-related ones with coworkers and bosses, clients and business associates. University students have bonenkai organized by clubs and associations. Community, neighborhood and senior associations have their own parties. The drinking continues well into January.

In December 2008, a 51-year-old primary school teacher that drank too much at year end party was killed in Kitakyushu when she leaned over the platform to get sick at a train station in Kitakyushu and was hit by an oncoming freight train. The driver of the train tried to stop. Vomit was found on the track.

New Year usually marks the beginning of a five or six day holiday period. Kids don’t go back to school until a week after New Year. By contrast in the West, the United States anyway, New Year has become an afterthought and signal that the holiday season is over and everyone is tired and broke and has to go to work or school the next day.

During the economic crisis in 2008 and 2009 companies cut back on their year-end party expenses, hosting modest catered parties in their offices that cost about $30 a head compared to more extravagant parties at fancy restaurants that cost about $50 a head.

New Year's Eve in Japan

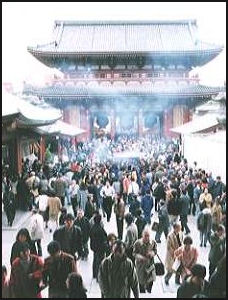

crowded temple on New Year At midnight, the Japanese don't uncork bottles of champagne and kiss each other. Instead, they visit a local Buddhist temple and form a line to take turns ringing a bell, 108 times, each peal representing a different, sin or vice such as jealousy or anger that is left behind in the old year. In addition, strips of wood with the names of the deceased are burned.

Later people move onto a Shinto shrine and form a line behind the main wooden shrine, ring a bronze bell, toss money into a grated collection box, clap to attract the attention of the local gods, bow and ask for protection in the coming year.

In some places, according to New Year custom that dates back to the 1300s, the head of the house goes through all the rooms at midnight, tossing toasted beans and shouting "Out with the demons! In with good luck!" For New Year’s Eve dinner many people have “Toshikoshi-soba” (“end of the year soba”). Afterwards the settle in front of the television to watch the “Red and White Sing Competition”, traditionally the highest rated television show if the year, of K-1 kick boxing. The featured guest at the Red and White show in 2009 was Susan Boyle, the Scottish singer who was a You Tube sensation when she appeared on the British television show “You’ve Got Talent” earlier in the year.

Before New Year, Buddhist priest thrown offerings of “ofuda” — wooden tablets containing religious messages onto holy bonfires to express thanks for divine protection for the past year. The tablets are often presented by temple supporters. The priests pray for the messages to be heard as the ofuda go up in flames. At some Shinto shrines priests rip apart large white sheets, representing the passing year’s impurities — or everyday misdeed committed by people.

New Year's Day Traditions in Japan

On New Year's Day many, most Japanese wish everyone they meet congratulations with the expression “”Omedeto gozaimasu”,” visit a Shinto Shrine and pray for good luck in the coming year, place items from the old year in a bonfire, and leave offerings of rice, vegetables and wrapped bottles of sake. Some people dress up in kimonos or nice clothes. Sometimes small gifts are exchanged but gift-giving generally isn't a big part of the holiday.

Kate Elwood wrote in the Daily Yomiuri: Like most people in Japan, I have wished many people a happy New Year over the past few weeks, and received similar good wishes in return. And as part of this routine, we've asked each other to keep on being nice to us in the current year, making use of the conventional and omnipresent entreaty, yoroshiku onegai shimasu. Even those who have had a death in their family in the previous year, and as a result traditionally refrain from the akemashite omedeto (happy New Year) part of the greetings, will nonetheless make the request for continued kindness. [Source: Kate Elwood, Daily Yomiuri, January 17, 2012]

Fortunes (“omikuji”) are determined by selecting bamboo sticks from a box and choosing a fortune according to the number on the stick or simply pulling a folded paper from a box. Luck is classified into “dai-ichi” (great luck), “kicki” (good fortune), “sho-kichi” (middle good fortune) and “kyo” (bad luck). If you like your fortune you can keep it. If you don’t like it you can tie it to a branch on a tree on the shrine grounds. The omikujo sheets include a horoscope-like predictions of the years events, with sections on business, health and love. Some larger shrines offer these in English.

When praying people toss some money into the offering box and say a prayer for a healthy and prosperous New Year. Many Japanese say that doing this makes them feel energized. The sake is usually free and offered to lift one’s spirits. Charms are available for specific tasks as well as for general purposes. They can be purchased for oneself, one’s family or friends or for a house, car, studies or pets. The previous year’s charms are sometimes tossed into a fire burning at the shrine.

As part of nationwide campaign to reduce dioxin pollution, objects such as amulets, prayers and arrows that have traditionally been burned in bonfires on New Year' Day and other holidays and festivals are now made from materials that don't produce dioxin when burned.

New Year Visits to Shrines and Temples

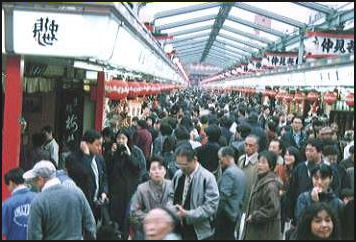

“During the New Year’s holidays, people go to shrines and temples to pray for health and prosperity in the year ahead. Families and friends go together to pay the first visits of the year, known as “hatsumode”, to Shinto shrines and Buddhist temples. In the case of Shinto shrines, these visits were traditionally made to shrines which are said to be in a “favorable direction” from the home of the visitor. The purpose of the visits was to pray for a rich harvest and the safety of the family and home during the year ahead. Meiji Jingu Shrine in Tokyo sees the largest number of “hatsumode “visitors (3.20 million in 2010), followed by Naritasan Shinshoji Temple in Chiba Prefecture (2.98 million in 2010) and Kawasaki Daishi Temple in Kanagawa Prefecture (2.96 million in 2010). [Source: Web-Japan, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Japan]

At the Shinto shrine, people are blessed in Shinto ceremonies (costing about $50 to $100 per family) and wait in line to ring a small bell and pray, drink hot sake, eat mochi (chewy rice cakes), exchange greetings and gossip with friends and relatives, and buy sheets of paper (“ omikujo”) that has ones fortune for the upcoming year and special arrows. According to Japanese tradition bows and arrows have magical powers that can repel evil spirits. Pink paper lanterns hang from the trees on the shrine grounds.

Describing the annual New Year's custom of hatsumode, Kevin Short wrote in the Daily Yomiuri, “Japanese like to start off the New Year with a visit to their favorite shrine or temple. Here they give thanks for blessings received during the past year, pray for health and success in the upcoming months, and buy an omamori charm sachet for their house or car. [Source: Kevin Short, Daily Yomiuri, January 5, 2011]

Hatsumode trips are all about counting your blessings, and acquiring luck and setting a pace for the upcoming year. Most people visit their small local temples and tutelary shrines, as well as one or more of the more famous regional institutions. Popular hatsumode spots include the Shinshoji temple in Narita, Chiba Prefecture; the Meiji Jingu shrine and the Sensoji temple in Tokyo; Kawasaki Daishi in Kanagawa Prefecture; Hikawa Shrine in Saitama Prefecture; Atsuta Jingu in Nagoya; Fushimi Inari Taisha in Kyoto; Sumiyoshi Taisha in Osaka; and Dazaifu Tenmangu in Fukuoka...

A record 99.39 million people visited Shinto shrines on the first three days of the new year in 2009. Meiji Jingu in Tokyo typically gets over a million visitors a day between January 1st and 3rd. To maintain ordered police or on hand and ropes are put in Palace to control the flow of human traffic.

In the first three days of 2009, Meiji Shrine in Tokyo received the 3.19 million visitors, the most of any shrine in Japan, followed by Shinshoji temple in Narita, Chiba Prefecture with 2.98 million. In 2008, 2.89 million visitors visited Indri Tisha shrine, dedicated to the god of harvests, in Kyoto. It took 12 employees five days to count all the money left at the 50 or so collection boxes at the shrine. In addition to cash offering people left lottery tickets and mochi rice cakes.

Japanese New Year's Games

In earlier times, almost all children took part in such special outdoor New Year entertainments as kite-flying and spinning tops (especially for boys) and a badmintonlike game for girls called “hanetsuki”. Indoor entertainments included “uta karuta “card games, which test the participants’ quickness at recognizing poems from the “Hyakunin isshu “(“Hundred Poems by One Hundred Poets”), and a board game called “sugoroku”, similar to backgammon. However, for present-day children, who are surrounded by so many different means of entertainment, these New Year's games have lost their former popularity.

Battledore and shuttlecocks (“hanetsuki”) is a New Year's game traditionally played by girls in kimonos. It is a netless badminton-like game in which players hit a shuttlecock with battledores (racket-like bats). It was first played to keep sickness and evil spirits from children. Another New Year's game played son some parts of the country involves throwing a fan to knock down a card.

Top-level “Hyakunin isshu “ matches are often televised the day after New Year Day. Players who are given a line from a poem and have to quickly slap a card with the correct poem on it. The poems come from “Ogura Hyakunin Isshu” (“One Hundred Poets, One Poem Each”), a classic collection of waka poems believed to have been compiled in the 13th century.

Edo koma tops are used to perform tricks and were traditionally spun during New year. They come in various sizes and shapes and are often painted red, black and gold and given a lacquer finish. The best ones are handmade using lathes from wood that has been aged for three years so that the top does not lose its spin after many years of use.

Kemari

“Kemari” is a traditional fom of kickball played by a circle of players that resembles kicking around a soccer ball or hackey sacked in a circle. Performed at a famous Shinto shrine in Kyoto after New Year by men in colorful, dress-like, traditional costumes, it is a simple game: the object is to kick a ball as many times as possible without letting it hit the ground. The 130-gram ball is made of deerskin patched together with horse hide “tape” and covered with a mixture of egg white, glue and white powder.

Kemari (also known “shukiku”) is usually played in a 15-square meter area with four species of forked trees in the corners. Each of the trees — a pine, cherry, willow and maple — is considered a dwelling place of gods. Players shout out the names of the gods who visited Fujiwara no Nariminchi, the Saint of Kemari, There are a number of religious rituals that accompany the sport such as placing the ball in the forks of the trees and saying prayers with it at an altar.

Kemari is believed to have been introduced to Japan from China in the 6th century. There are records of it being played at Hokoji Temple in Nara in A.D. 644. In the Heian Period (794-1192) the game was compulsory for court nobles. In the Kamakura period (1192-133) it was popularized by samurai.

The players are supposed to have an erect posture and keep their arms glued to their side like Riverdancers and the kick the ball with the instep of the foot. The color of the costumes worn by the players indicates their skill level. One player told the Daily Yomiuri, “An ideal flick of the ball contains a moderate spin, makes a clear sound like a tsuzumi spin and should not be too low or too high.” Kemari is often played as an exhibition. In 1992, U.S. President George Bush joined in a game and enjoyed it so much he kept Air Force 1 waiting as kept trying it again.

Japanese New Year's Day Foods

On January 1, families gather at breakfast to drink a special kind of sake that is supposed to ensure long life and to consume a special soup called “zoni”, containing “mochi” (very chewy blob-like rice cakes), vegetables and other ingredients that vary depending on the region.

Other foods, with symbolic meaning, are eaten. These include “kazunoko” (salted herring roe, symbolizing fertility), “gomame” (dried sardines cooked in soy sauce, symbolizing a good harvest), “kinton” (mashed sweet potatoes and chestnuts, symbolizing wealth), “datemaki” (sweet omelet squares, symbolizing civilization), “khaki namusu” (shredded persimmon, radishes and carrots, symbolizing peace), and kuwai (arrowroot bulb, symbolizing hope and prosperity), “kamaboko” (fish paste made from the flesh of several different kinds of fish placed in wood and steamed), “tazuuri” (roasted small sardines) and “kuromame” (black beans, symbolizing hard work and good health). The word for beans, “mame” also means healthy.

“Kobumaki” is made of rolled kombu kelp, usually from Hokkaido, tied with a kampyo gourd and then simmered in a pot. The link with a happy life comes from the association of “kobu” (another word for kelp) and “yokokobu” (meaning “to be delighted”).

“Nishiki tamago” (an egg brocade) is made from separated egg yokes and whites with the yokes representing gold and the whites representing silver. Nishiki refers to a piece of silk fabric folded into a design using gold and silver thread, and tamago represents a prayer for economic prosperity.

“Kohaku kamaboko” — red and white fish cakes — are one of the most popular oseshi items. The red color represents happiness and a good mood. White is a symbol of purity. The color combination suits the sacred but festive nature of the holiday and is also used in mochi given away during weddings and the completion of the framework of a new house.

“Kurikinton” — a mixture of sweet potatoes and chestnuts’symbolizes prosperity with with its golden, yellow color. Chestnuts have a long association with good luck and were eaten before heading off to war in the old days. The dish is made with a lot of sugar and was considered quite a delicacy in the old days when sugar was very expensive.

Making delicious, soft “kuromame” takes some skill. It used to be said that a woman earned her right to be a bride when was able to make tasty kuromame. The word “mame” means brisk and healthy. Black beans are rich in protein and before meat-eating became widespread was a staple dish.

“Datemaki “’steamed fish-and-egg rolled cakes — and rolled items like scrolls are associated with festivities and family treasures.

Prawns cooked in sake and soy sauce symbolize the prayer to live a long healthy life, until your back curls up. The antennae represent whiskers, a symbol of a person who has lived a long life. Large shrimp are used as New Year’s decorations. “Tazukiri”’small dried sardines cooked in sugar and soy sauce — means “to cultivate a rice paddy.” As fish were traditionally used to fertilize rice fields, this dish symbolizes the hope of an abundant harvest.

New Year delicacies, known as “oseshi” in Japanese, are often served in “jubako”--four lacquered boxes that are set on top of one another on a fifth box left empty to show the arrangement is incomplete and there is room for improvement. Many of the dishes require considerable effort to make and should be offered to the gods and dedicated to them before being served to people. They are painstakingly made before New Year’s Day “ or bought “ and eaten during the first three days of the new year. The meals are prepared with prayers for health, family, safety and family prosperity and the dishes symbolize the luscious, plentiful foods provided by the mountains and sea.

Tamako Sakamoto wrote in the Daily Yomiuri: None of my children are particularly crazy about osechi... but they would definitely be disappointed if they were served an American-style breakfast or a regular Japanese breakfast on Jan. 1. Osechi seems to be a special symbol that brings the joyous feeling of the New Year. So even if I do not have enough time to cook the most time-consuming osechi dishes, I serve my family at least a simple osechi meal and zoni (soup with vegetables and mochi). [Source: Tamako Sakamoto, Daily Yomiuri, December 30, 2011]

Yuzu

Tamako Sakamoto wrote in the Daily Yomiuri: To produce the special atmosphere of the New Year's table, there is a magic fruit that gives everything "the fragrance of the New Year." That is yuzu, my favorite citrus. A few weeks ago, when I received a paper bag full of this unique fruit from a neighbor who has a yuzu tree, I cooked clear soup for dinner and added a small piece of yuzu to each bowl. When I served it to my children, all of them said, "It smells like Oshogatsu [New Year's]!" [Source: Tamako Sakamoto, Daily Yomiuri, December 30, 2011]

Yuzu, a winter fruit, is too sharp to eat fresh because of its strong and penetrating aroma, but it has a variety of uses. For example, on the day of toji (winter solstice), yuzu-yu--taking a hot bath with yuzu floating in it--is customary. When I was a child, my mother made a small bag of soft cotton cloth, put plenty of yuzu in it, and put the bag in the bathtub so that we could enjoy aromatic yuzu water, which is said to be good for the skin.

On Jan 1, when we eat zoni, the final step in preparing it is to scrape off small bits of yuzu zest and place them on top of each serving of zoni in wooden bowls. The wonderful aroma, a mixture of the savory soup and the yuzu fragrance, makes everybody feel that the New Year has come. Even if you resort to store-bought osechi dishes, you can still scoop the yuzu pulp out of its rind to make a yuzugama (a yuzu cup or pot) and arrange some simple appetizers in it to give your dining table a special New Year's atmosphere. When I make osechi, which is presented in a multitiered lacquer box, I make it a rule to include a yuzu cup with ikura salmon roe or yuzu-flavored kohaku namasu (red and white marinated daikon and carrot).

During the winter, I make various yuzu desserts as well--cookies with yuzu icing, yuzu cheesecake, yuzu madeleines and so on. If you suddenly decide to visit your friends or relatives and can't think of what to bring, I recommend baking yuzu madeleines, which can be easily made in half an hour. This very simple homemade confection with yuzu fragrance is sure to please anyone and makes an apt gift for the New Year's period. And yuzu sweets aren't limited to madeleines. Simply replacing the lemon juice in your dessert recipes with double portions of freshly squeezed yuzu juice is all it takes to create your own original yuzu treat. Even store-bought plain cookies can become your own original ones with yuzu icing.

So, if you feel it is too late to prepare special dishes for the New Year, I recommend that you buy a small basket of yuzu, preferably small, golfball-sized yuzu with leaves, at a grocery store. They will give your kitchen a very special atmosphere and will definitely be enjoyed in various ways during the New Year's holidays!

Kevin Short wrote in the Daily Yomiuri: Yuzu is a tart, highly aromatic citrus fruit originating in China. One of the most cold-tolerant of the citruses, some botanists now believe that it may actually be a hybrid species. The fruit, usually about baseball size or a bit smaller, is more yellow than orange, though not quite as yellow as a lemon. The waxy surface is pocked with numerous bumps and indentations. The leaf is evergreen, with a distinctive petiole at the base. [Source: Kevin Short, Daily Yomiuri, December 20, 2012]

Yuzu juice is a major ingredient in ponzu sauce, a dip used for various Japanese dishes such as shabu-shabu and yudofu; while the rinds are made into marmalade, or mixed into chawan-mushi pudding and suimono clear soup consomme. Dried, crush rind is sometimes added to the shichimi-togarashi "seven-ingredient" spice mix. My farmer friend always saves me a basket of yuzu fruits that are oddly shaped or have suffered some damage or blemishes that make them unsuitable for market. I plan not to eat them, but to float them in the bathwater on the winter solstice. This tradition, called yuzu-yu, celebrates the rebirth of the sun, and is also said to help prevent colds and chilblains. Some public baths and Japanese style inns may feature yuzu-yu baths on and around the solstice. Also, coffee shops and restaurants may offer a hot, throat-soothing drink called yuzu-cha, with tart yuzu rinds mixed with sweet honey, as a seasonal menu.

Harvesting Herring Roe

“Kazunoko” (salted herring roe) is bright yellow in color and said to bring good luck. Kazunoko’s association with fertility is linked to the fact that there are tens of thousands of eggs in a herring’s ovaries. The highest quality roe taken from herring caught off Hokkaido sells for $100 a kilogram.

In a custom that has been described as deeply rooted in Japanese culture as the eating of turkey on Thanksgiving in America, millions of Japanese consume “kazunoko”, or herring row as part of their New Year's celebration. "The thick clusters of tiny golden eggs found in the female fish when they are ready to spawn," wrote Jon Krakauer in Smithsonian magazine, "are marinated in sweet sake and soy sauce and then served uncooked as sushi, artfully arranged with seaweed and a dollop of rice on a special ceremonial plate." [Source: Jon Krakauer, Smithsonian, October 1986]

Eating kazunoko, which is supposed to increase fertility, has been compared to "chewing on salty rubber BB's." Sometimes referred to as "yellow diamond," the finger-length sacs of roe sell for a $100 a pound or more. Since the fish have been fished to extinction in Japanese waters, demand is met with an estimated annual catch of one billion Pacific herring caught along the North American coast, mostly off of Alaska and British Columbia.

Much of the herring is harvested in waters off the Alaskan island of Sitka. During a fishing season that can last less than three hours, fisherman can make up to a half a million dollars for a single 400 ton catch.

Only 52 boats have licenses to catch herring and these license sell for up to $210,000 a piece. To locate and track the schools of herring the fisherman use sophisticated echo sounders and spotter planes. Once a school has been located competing fishing boats jockey for position so they encircle the school with a net and pump the fish on to the boat.

One fisherman, who netted 400 tons of fish but was only to pump a 100 tons aboard his ship, told Krakauer: "the fish started running straight for the bottom and we couldn't stop them. The net when sown and then the boat started going over. The rail went over, and there was water on the deck halfway up the hatch coming. When you see something like that happening you don't hesitate. We cut the lines, the bridles cut everything loose. Otherwise we would have gone to the bottom with the fish."

Japanese New Year's Day Customs

tying fortunes Entrances to homes and automobile grills are adorned with small shrines made of pine branches, bamboo and straw that welcome the gods, good luck and keep demons and impure things from entering; houses are scrubbed clean; old debts are settled; and people stop by the homes of friends and relatives to exchange New Year's greetings.

A set of white kagamimochi, literally "mirror-shaped rice cake," is indispensable at New Year's and is used as an offering to deities on the holiday. Explaining how to make round kagamimochi, Koyo Hayashi, president of the Hayashi Nosan mochi-making company told the Yomiuri Shimbun. "We first cut freshly pounded mochi in the proper size, then stretch the edges of the mochi before folding it. By repeating the process, a round mochi is formed.” Employees at the create beautiful round kagamimochi by repeating the procedure about 20 times. [Source: Yasushi Wada, Yomiuri Shimbun, January 1, 2011]

In the old days, children enjoyed traditional New Year's activities such as playing battledore (a badminton-like game), spinning tops, flying kites and playing “sugoroku” (a Japanese version of Parcheesi). These games are still played but, nowadays, as is the case with American children, Japanese children mainly sit around and play video and computer games. Some kids spend their holidays studying for important exam in February.

Kids receive envelopes filled with cash from the parents, grandparents, uncles, aunts and close family friends. In recent years it is not unusual for junior high and high school students to receive 5,000 yen ($60) or 10,000 yen ($120) per gift. When all the “otoshidama “are put together, they may amount to several tens of thousands of yen. Older children receive more than younger kids. Many middle school kids get $400 or more for their New Year’s gifts. They average for all children is about $230 (2005). In 1997 they received more, about $270. Some kids rush out an buy stuff, many of them video games. Others put their money in bank accounts, many because their parents force them to.

Watching the sunrise on New Year’s Day, preferably from a mountain top while the rises from the sea, is a big deal. Some people begin hikes at 2:00am to reach the summit of mountains to catch the sunrise. Cruises companies in Tokyo offer special sunrise cruises, Tokyo Tower, the skyscraper Sunshine 60 and Yokohama Landmark Tower all open at 6:00am on New Year’s Day to allowed people to see the sunrise. In much of Japan, the trains run 24 hours.

In Tokyo, may people do a mini pilgrimage to seven shrines located between Ueno Park and Tabata Station. Each one of the seven shrine is associated with one seven gods of good luck (See Superstitions). The “pilgrims visit each shrine and get a stamp on their card that says that went there. The stamp sheets cost ¥1,000, each stamp costs ¥200. The shrines can be visited between January 1st and January 15th. Similar pilgrimages can be done in Kamakura and other places,

Mochi, New Year's Rice Cakes

making mochi For hundreds of years, New Year's Day has been celebrated in Japan with the consumption of “mochi”, a soft, chewy blob-shaped rice cake which can be eaten raw, boiled, toasted or grilled or placed in a soup. Along with sake, it is one of the most popular offerings to the Gods.

Mochi has been around for at least 1000 years. In the old days, the rice for mochi was pounded by men using sledgehammer-size wooden mallets and the pounded rice was steamed for 40 minutes into a smooth paste and then shaped by women into mochi.

Today, mochi is made primarily made at rice stores and confectionery shops or in big factories with special rice-kneading machines. Families sometimes put some mochi on small stool-like alters, which are taken to the local Shinto shrine and placed on shelves with tags that identify the families who offered them.

Rice has religious significance in Japan and mochi is considered a symbol of happiness. It is also eaten at festivals, weddings, the building of a new house and other occasions. The New Year's shrine at the entrance to the house usually contains two large circular slabs of mochi that are stacked one on top of the other with an orange, some straw and other decorations on top of that.

Deaths from Eating Mochi

making mochi Mochi is extremely chewy and sticky. Each year several people die from choking to death on it when it gets struck in their throat. Most of the victims are older people. The problem is so serious that fire departments are put on alert for mochi emergencies and newspapers report the death toll from mochi-eating, much as American newspaper list holiday traffic deaths. In 1995, 11 people choked to death from eating mochi nationwide and ambulances responded to 28 mochi emergencies in Tokyo alone. [Source: Washington Post]

The Tokyo fire department advises elderly people in particular to cut the mochi into small pieces, "wet the throat, chew it fully and then swallow" and recommend that the mochi be eaten in the presence of others. Using a vacuum cleaner is the best way to get mochi un stuck in someone’s throat. In a famous scene from the Japanese movie “Tampopo”, an old man choking on mochi is first turned upside down and when that doesn’t a vacuum cleaner nozzle is jammed down his throat and the mochi is sucked pu.t

In the 2006-2007 New Years season four men ranging in age from 68 to 89 died from choking on mochi cakes. In 2008, two people — a 53-year-old man and a 89-year-old man — died from choking on mochi in Tokyo and 13 others were hospitalized for choking on mochi.

There were six mochi deaths in the Tokyo during the 2010 New year weekend. Twenty-four people were hospitalized after choking on mochi. The six that died were between 75 and 95. One of them, a 66-year-old woman, died after being given complimentary pieces of mochi at a pachinko parlor.

New Year Cards in Japan

making mochi Another fixture of New Year’s in Japan is the sending of “nengajo”, New Year's cards. More than 4 billion special New Year's postcards (more than the total number of Christmas cards delivered in the United States in all of December) are delivered on a single day — New Year's Day — by an army of a half million postal workers that fan out across Japan in trucks, vans, cars, scooters and bright red bicycles. [Source: T.R. Reid, Washington Post]

During the three days that follow New Years Day an additional 2 billion cards are delivered, mainly to businesses closed during the holidays or from people who received a card from someone they didn't mail a card to. The postal service makes sure that every household in Japan gets at least one card. Most households get over 100 cards and some get thousands. The number of “nengajo “sent for New Year's Day in 2011 was approximately 2.08 billion.

In one survey 55 percent of Japanese said that New Years cards were a chore but 82 percent said they would send them anyway.

The Japanese have exchanged New Year's greetings since ancient times. In the Heian period (794-1192), court nobles are believed to have exchanged letters containing waka poems at the start of a new year. The modern custom of mailing New Year's cards toward the end of one year and having them delivered on or around Jan. 1 of the next originated in the Meiji era (1868-1912), when the state-run mail delivery system was established. Post offices started selling New Year's cards with lottery numbers on them in 1949. [Source: Yomiuri Shimbun, November 22, 2011]

In recent years, the number of people sending New Year's cards has been gradually decreasing in part because there has been an increase in the number of people who extend New Year's greetings by e-mail instead of cards. In 2011 about 3.82 billion New Year's cards were issued, about the same as the previous year.

In 2011 post offices started accepting New Year's cards on December 15. They were delivered to recipients on Jan. 1 if they were posted by December 25.

Local New Year Celebrations

On New Years Eve the people of the Oga Peninsula in the Akita Prefecture enage in the unique Namahage Festival, in which young men dressed as demons go from door to door frightening children into behaving themselves. In Matsunoyam, Niigata Prefecture, “son-in-laws” are tossed into snow drifts.

In Kyoto, Yasakajinja shrine features a rite called “ okera mairi” in which people throw little bits of rope into a ceremonial fire and collect embers which are used to light candles at home which are cusped to ensure good health. At the shrine people play a “ karuta” , a game in which participants dressed on Heian period costume slap cards with poetic verses on them. At Shimogamojinja shrine men kick around ball in a game called “ kemari” . During the Shigyoshiki New Year ceremony geiko and maiko appear wearing hair ornaments made of rice plants and formal black kimonos with patterns at the bottom.

Ringing the massive bell at Chionin Temple in Kyoto is an important New Year’s event. It takes 17 monks to ring the bell, 16 of them to raise the giant wooden hammer, which they do by pulling on the ropes, swinging it away from the bell, while the 17th monk hangs from the striking end, ready to push off with his legs in the split second before impact. The chime produced by the bell lasts for 20 minutes. The event is often shown at New Year’s broadcasts.

Fukubukuro Lucky Bags and After New Year's Day Customs

Stores reopen after the holidays with big sales in which customers form long lines to get their hands on “Fukubukuro” (“lucky bags”) filled with miscellaneous items worth several times the price of the bags). A standard lucky bah sells for ¥10,500 and typically had famous band name good inside that are valued at around three times the bag’s value.

The lucky bags are available at all the major department stores. Often all the available bags are snatched up within seconds after the store opens. Sometimes thousands wait outside the doors of a store and make a mad dash to the counter where the bags are sold when the doors open. High-end “Dream for a New Year” “fukubukuro“ offered by the Mitsukoshi flagship department store including an Antarctic cruise for $20,000; three French artworks for $240,000; and a sashimi party for 100 people for $6,000.

After New Year there are also a number of events in which people take swims in cold rivers or sea water or douse themselves with cold water or stand under frigid waterfalls.

Surugadako kites are popular New Year’s decorations. It is said they created to celebrate the victory of the general of the famous warlord Imagawa Yoshimoto during the Warring States period (1467-1568). Military figures and kabuki actors are often depicted on the kites. In some places they are still made from bamboo the traditional way and painted by hand.

Sales of Fukubukuro Lucky Bags Up in 2013

The Yomiuri Shimbun reported: “As New Year's opening sales kicked off, major department stores in central Tokyo said sales were up from the same period last year. Fukubukuro lucky bags of brand-name women's clothing sold out shortly after the opening of Takashimaya's Nihonbashi store in Chuo Ward. The store sold 4 percent more on the day than it did last year.

Customers buy fukubukuro without knowing the lucky bags' precise contents. At Matsuya Ginza in the ward on the same day, lucky bags of popular brands of ladies' wear sold out in one minute and 51 seconds. Other lucky bags containing jewelry and furs also sold out in about an hour.

About 20,000 people stood in line for the opening of a sale at Seibu's Ikebukuro flagship store in Toshima Ward. Lucky bags of women's clothing--priced at about 10,000 yen to 20,000 yen--and food products sold especially well. The store sold on the day 20 percent more than it did on its Jan. 2 opening day in 2012.

New Fukubukuro Lucky Bag Promotions

Satoshi Takizawa wrote in the Yomiuri Shimbun: “The newest fukubukuro selections--most of which are designed to make buyers feel they are playing a more active role in their world--are extremely limited. Only a few shoppers will be lucky enough to buy one. "Dream" fukubukuro used to contain luxury items, including solid-gold objects. Over the past few years, however, "experience-based" fukubukuro have grown in popularity as a means to make buyers' dreams come true at a relatively cheap cost. [Source: Yomiuri Shimbun, December 28, 2012]

The most popular ones are bags for children and their parents. Keio department store in Shinjuku, Tokyo, will offer opportunities for primary school students to try their hand at anime production. The company that creates the TV anime series Sekai Meisaku Gekijo (World Masterpiece Theatre) is offering children and their parents a lesson from a professional voice actor and a chance to experience a voice-over of Akage no An (Anne of Green Gables). It sells for 10,000 yen and is limited to two parent-child groups.

Mitsukoshi department store in Ginza, Tokyo, launched a fukubukuro project in which a family will be featured in Keiri Otsuka's manga series Uchino Tama Shirimasenka? (Have you seen my Tama?), to be issued in a picture book magazine this spring. It sells for 30,000 yen and is limited to one family with children ages 4 to 8.

For those looking for romance next year, fukubukuro are on offer that allow buyers private access to the Tokyo Skytree's observation deck. The package is available for five couples, who can have the spectacular night view from the tower to themselves for 10 minutes starting about midnight after the observatory closes. It sells for 100,000 yen at several outlets, including Tobu department store in Ikebukuro, Tokyo. Printemps Ginza and Hankyu Men's Tokyo, both in Tokyo, will release "Ginza/Yurakucho de Depakon Fukubukuro." The bag contains clothing and accessories good for a date. In addition, a matchmaking event called "Depakon"--a term combining the abbreviations of department store and konpa (matchmaking party)--will be held at the stores' cafe in February. Bachelors who are aged 20 and older and buy the bag will get a ticket to attend the Depakon.

In addition to interactive fukubukuro, some department stores are releasing grab bags offering furnished houses for reasonable prices. Due to the prolonged business slump, many department stores are featuring practical items and food in their bags. At Iwataya department store in Fukuoka, customers can choose five items from a selection of 20 houseware goods, including things such as kettles and doormats. Fukubukuro are limited to 200 sets for 10,500 yen a piece.

Experiential fukubukuro by department stores include: 1) Be a hula girl! by Shinjuku Takashimaya (15,000 yen, 1 woman). Dance with professional hula girls at Spa Resort Hawaiians in Fukushima Pref. 2) Be an employee of Sumida Aquarium by Tobu Ikebukuro store and others (2,013 yen, 4 primary school students). Feed penguins at an aquarium. 4) Appearance in musical 'Eden no Tohoku' by Mitsukoshi Nihonbashi (20,000 yen, 20 parent-child pairs). Appear in a scene of the musical. 5) D Kids wiz Kenzo limit school by Tokyu Toyoko store and others (3,000 yen, 40 primary school students). Take a street dance lesson from popular group Da Pump member Kenzo. 6) Bags of Uonuma's Koshihikari brand rice by Yokohama Takashimaya and others (5,000 yen, 3 people). 20 kilograms of rice is delivered from Niigata every month January to August.

Image Sources: 1) photos by Ray Kinnane and Jun at Goods from Japan, 2) illustrations JNTO

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Daily Yomiuri, Times of London, Japan National Tourist Organization (JNTO), National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated January 2013