KOFUN PERIOD (A.D. 3RD CENTURY–538)

arial shot of a kofun

The Kofun period (ca. A.D. 250-ca. 600) takes its name, which means old tomb (kofun) from the culture’s rich funerary rituals and distinctive earthen mounds. The mounds contained large stone burial chambers, many of which were shaped like keyholes and some of which were surrounded by moats. By the late Kofun period, the distinctive burial chambers, originally used by the ruling elite, also were built for commoners. [Source: Library of Congress *]

Koji Takahashi, a Toyama University archaeologist, told National Geographic News: “It was during the Kofun period that the Japanese nation was established on the Japanese archipelago.” Charles T. Keally wrote: “The Kofun sees the full development of the early Japanese state, and it is a time of close contacts with the continent, especially with the Korean kingdoms. In one sense, the Kofun Period marks the end of Japanese prehistory -- it lacks any significant contemporary written records. But in another sense, the Kofun Period is the beginning of Japanese history -- for there are many records compiled just after the period closed, and these records are based on older, contemporary documents that were destroyed or on oral histories still circulating at that time. The Kofun Period is Japan’s protohistoric period.” [Source: Charles T. Keally, Professor of Archaeology and Anthropology (retired), Sophia University, Tokyo, t-net.ne.jp/~keally/kofun ++]

The Kofun Period was politically a relatively unstable period where the Royal or Imperial authority was concerned, owing to the constant disputes between clans which had conflicts of interest and power struggles. The period is seen as ending by around A.D. 600, when the use of elaborate kofun by the Yamato and other elite fell out of use because of prevailing new Buddhist beliefs, which put greater emphasis on the transience of human life. Commoners and the elite in outlying regions, however, continued to use kofun until the late seventh century, and simpler but distinctive tombs continued in use throughout the following period. *

RELATED ARTICLES IN THIS WEBSITE: ANCIENT HISTORY factsanddetails.com; ASUKA, NARA AND HEIAN PERIODS factsanddetails.com; KOFUN PERIOD, CLANS AND EARLY YAMATO RULERS factsanddetails.com; YAMATO AND QUEEN HIMIKO factsanddetails.com; MYTHICAL ORIGINS OF JAPAN, THE JAPANESE AND THE JAPANESE EMPEROR factsanddetails.com; WA AND EARLY CONTACTS BETWEEN CHINA AND JAPAN actsanddetails.com; KOFUN RELIGION factsanddetails.com; KOFUN PEOPLE AND LIFE (A.D. 3RD CENTURY–538) factsanddetails.com; KOFUN PERIOD (A.D. 3RD CENTURY–538) KOFUN AND TOMBS factsanddetails.com; KOFUN-ERA JAPAN, CHINA AND KOREA: RELATIONS, INFLUENCES AND TRADE factsanddetails.com

Websites: Yamato Period Wikipedia article on the Yamato period Wikipedia article ; Kojiki, Nihongi and Sacred Shinto Texts sacred-texts.com ; Imperial Household Agency kunaicho.go.jp/eindexList of Emperors of Japan friesian.com ; Buddhism and Prince Shotoku onmarkproductions.com ; Essay on the Japanese Missions to Tang China aboutjapan.japansociety.org . References: 1) The Chronicles of Wa, Gishiwajinden by Wes Injerd; 2) Wa (Japan), Wikipedia; 3) Excerpts from the History of the Kingdom of Wei, Columbia University’s Primary Source Document Asia for Educators. Asuka Wikipedia article on Asuka Wikipedia ; Asuka Park asuka-park.go.jp ; Asuka Historical Museum asukanet.gr.jp ; UNESCO World Heritage sites ; Early Japanese History Websites: Aileen Kawagoe, Heritage of Japan website, heritageofjapan.wordpress.com; Essay on Early Japan aboutjapan.japansociety.org ; Japanese Archeology www.t-net.ne.jp/~keally/index.htm ; Ancient Japan Links on Archeolink archaeolink.com ;Essay on Rice and History aboutjapan.japansociety.org ; Metropolitan Museum of Art Department of Asian Art metmuseum.org; Wikipedia article on the Jomon Wikipedia ; Historical Parks Sannai Maruyama Jomon Site in Northern Honshu sannaimaruyama.pref.aomori.jp ; Yoshinogari Historical Park yoshinogari.jp/en ;Good Photos of Jomon, Yayoi and Kofun Sites at Japan-Photo Archive japan-photo.de ; Wikipedia article on the Ainu Wikipedia ; Good Japanese History Websites: ; Wikipedia article on History of Japan Wikipedia ; Samurai Archives samurai-archives.com ; National Museum of Japanese History rekihaku.ac.jp ; English Translations of Important Historical Documents hi.u-tokyo.ac.jp/iriki

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: “Burial Mounds in Europe and Japan: Comparative and Contextual Perspectives (Comparative and Global Perspectives on Japanese Archaeology) by Thomas Knopf, Werner Steinhaus, Shin’ya Fukunaga Amazon.com; “State Formation in Japan: Emergence of a 4th-Century Ruling Elite” (Durham East Asia Series) by Gina Barnes (2006) Amazon.com; “Sacred Texts and Buried Treasures: Issues in the Historical Archaeology of Ancient Japan” by William Wayne Farris Amazon.com; “Paekche of Korea and the Origin of Yamato Japan” (Ancient Korean-Japanese History) by Wontack Hong Amazon.com; “Reading the Treatise on the People of the Wa in the Chronicle of the Kingdom of Wei”: The World’s Earliest Written Text on Japan by Arikyo Saeiki and Joshua A. Fogel (2018) Amazon.com; “Japan in Five Ancient Chinese Chronicles: Wo, the Land of Yamatai, and Queen Himiko” by Massimo Soumaré, Mark Hall, et al. Amazon.com; “Himiko and Japan's Elusive Chiefdom of Yamatai: Archaeology, History, and Mythology” by J. Edward Kidder Jr Amazon.com; “The Archaeology of Japan: From the Earliest Rice Farming Villages to the Rise of the State (Cambridge World Archaeology)” by Koji Mizoguchi Amazon.com; “An Illustrated Companion to Japanese Archaeology (Comparative and Global Perspectives on Japanese Archaeology)” by Werner Steinhaus, Simon Kaner, et al. (2020) Amazon.com; “Life In Ancient Japan” by Hazel Richardson Amazon.com; “Daily Life and Demographics in Ancient Japan” (Michigan Monograph Series in Japanese Studies) (2009) by William W Farris Amazon.com; “Archaeology of East Asia: The Rise of Civilisation in China, Korea and Japan” by Gina L. Barnes Amazon.com; “The Cambridge History of Japan, Vol. 1: Ancient Japan” (Volume 1) by Delmer M. Brown Amazon.com

Kofun Period Achievements

5th century iron and gilt copper helmet

During the Kofun period, a highly aristocratic society with militaristic rulers developed. Its horse-riding warriors wore armor, carried swords and other weapons, and used advanced military methods like those of Northeast Asia. Evidence of these advances is seen in funerary figures (called haniwa; literally, clay rings), found in thousands of kofun scattered throughout Japan. The most important of the haniwa were found in southern Honshu--especially the Kinai Region around Nara--and northern Kyushu. Haniwa grave offerings were made in numerous forms, such as horses, chickens, birds, fans, fish, houses, weapons, shields, sunshades, pillows, and male and female humans. Another funerary piece, the magatama, became one of the symbols of the power of the imperial house. [Source: Library of Congress *]

Aileen Kawagoe wrote in Heritage of Japan: The irrigation techniques of the day were extremely advanced; the construction techniques for building the tombs were mind-blowing; and as the tombs got more massive and monumental in size, so did the treasures within them – the technology for all these achievements is attributed to influences from the Asian continent. The period is protohistoric, which means that while Japan didn’t yet have its own written language, there were historical records and chronicles by neighboring peoples on the Chinese continent and the Korean peninsula, snatches of which, described events and happenings of the Kofun period. [Source: Aileen Kawagoe, Heritage of Japan website, heritageofjapan.wordpress.com]

The Kofun period was a critical stage in Japan’s evolution toward a more cohesive and recognized state. This society was most developed in the Kinai Region and the easternmost part of the Inland Sea (Seto Naikai), and its armies established a foothold on the southern tip of Korea. Japan’s rulers of the time even petitioned the Chinese court for confirmation of royal titles; the Chinese, in turn, recognized Japanese military control over parts of the Korean Peninsula. *

More exchange occurred between Japan and the continent of Asia late in the Kofun period. Buddhism was introduced from Korea, probably in A.D. 538, exposing Japan to a new body of religious doctrine. The Soga, a Japanese court family that rose to prominence with the accession of the Emperor Kimmei about A.D. 531, favored the adoption of Buddhism and of governmental and cultural models based on Chinese Confucianism. But some at the Yamato court--such as the Nakatomi family, which was responsible for performing Shinto rituals at court, wanted to keep the status quo in place. Battles over which religion would dominate occurred. *

Kofun

3-D mapping of a kofun

The Kofun period is named after kofun — gigantic earthen burial mounds (tumuli). First were built for important people and often surrounded by a moat, they came in different shapes — round-, square- and keyhole-shaped — and were similar to graves found in China and Korea.

The largest tombs were keyhole-shaped. Some covered four or five acres. They first appeared in the Yamato region of present-day Nara Province in the late 3rd and early 4th centuries A.D. and spread to northern Honshu and southern Kyushu by the end of the 4th century. The spread of these tombs is offered as proof of the spread of Yamato culture. Why were the many of mounds keyhole shaped? No 0ne know for sure. One theory is that the shape was meant to looks like a horse’s hoof. Others reason the Kofun-era people experimented with various shapes, and simply liked the “keyhole-shape”.

Inside excavated tombs archaeologists have found mirrors, swords, armor, earrings, bracelets, equestrian gear, crowns, shoes, terra cotta figures, and personal ornaments made from precious beads and worked gold and copper. The ancient Japanese, like their Chinese counterparts, probably believed they could take these objects with them to the next life. Earthenware cylinders, haniwa clay figures, and sculptures, some as tall as 1½ meters, surrounded the kofuns.

According to the Metropolitan Museum of Art: “ The practice of building sepulchral mounds and burying treasures with the dead was transmitted to Japan from the Asian continent about the third century A.D. In the late fourth and fifth century, mounds of monumental proportions were built in great numbers, symbolizing the increasingly unified power of the government. In the late fifth century, power fell to the Yamato clan, which won control over much of Honshu island and the northern half of Kyushu and eventually established Japan’s imperial line.” [Source: Metropolitan Museum of Art Department of Asian Art, "Kofun Period (ca. 3rd century–538)". Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History, October 2002. metmuseum.org ]

There are about 30,000 kofun mound tombs in Japan. These date from the 3rd century to the 7th century. Of these, 188 are designated as ryo, the tombs of emperors and empresses, and another 552 are designated as bo, the tombs of other members of the royal family. There are 46 more designated as ryobo sankochi, or possibly the tombs of members of the imperial family, and 110 other types of "burials" that are treated the same way as imperial mound tombs. These 896 tombs and "burials" are centered on the Kinki District. They were officially designated at the end of the Edo Period and the Meiji Period, based on the Kojiki, Nihon Shoki, Engishiki and other ancient documents. About 600 decortated tombs are known, from Kyushu in the south to the southern part of Tohoku in the north. These date to the 5th and 6th centuries. They are about 1 percent of the total known mound tombs.

Dating the Kofun Period

Haniwa tomb figures

Keally wrote: “Archaeologists place the beginning of the Kofun Period at the time the first keyhole-shaped mound tombs appeared. Mounds on burials began several centuries earlier in the Yayoi Period. Similar round and square mounds with moats continued all through the Kofun Period, although the Kofun burial was placed in the top of the mound instead of under it, as in the Yayoi Period. But the keyhole shape is thought to mark imperial mounds and hence to mark a transition in cultural evolution worthy of a new name for the subsequent period. [Source: Charles T. Keally, Professor of Archaeology and Anthropology (retired), Sophia University, Tokyo, t-net.ne.jp/~keally/kofun ++]

“The date of the first keyhole-shaped mound tomb generally has been given as about 300 A.D. Recent discoveries, however, push that date back 25-50 years, almost to the time of Queen Himeko’s death. The date for the end of the Kofun Period is placed variously at 552 (the official date for the introduction of Buddhism) or 710 (the date of the move to the Heijo-kyo capital). ++

“The "history" of the Kofun Period depends on outside sources, first Korean records, then both Chinese records and the early Japanese writings from the Nara Period in the early 8th century. There are no Chinese records on Japan from 266-413. The 4th-century Korean records, though, tell of considerable interaction between the Korean kingdoms and Wa, and of Wa’s military intervention on the peninsula. The Chinese records of the 5th century show that the developing Yamato Government was again in close contact with China. This is probably the time when writing was first introduced to Japan. The Japanese Kojiki (712), the various Fudoki (713), and the Nihon Shoki (720) pick up the story, in hindsight, from the 6th century.

Kofun Period (ca. 3rd century–538 A.D.) and Asuka Period (A.D. 538 TO 710)

Kawagoe wrote: The last two centuries of the Kofun period is known as the Asuka period when Buddhism teachings and art arrived and proliferated throughout the land, with Asuka city as the center of Buddhist enlightenment. Buddhism along with a new administrative and bureaucratic system were introduced by large numbers of incoming toraijin immigrants mainly from the Korean peninsula most of whom came to stay on and integrated with the Yamato society. However, the spread of the Buddhist religion and the ensuing temple-building activities requisitioned all he labour and efforts previously expended on building large tumuli so the Kofun culture came to an end. [Source: Aileen Kawagoe, Heritage of Japan website, heritageofjapan.wordpress.com ]

Keally wrote: Buddhism was introduced into the country in the 6th century, “the Korean-related Soga and the native Mononobe clans struggled over the primacy of Buddhism or the native religion, the Yamato forces conducted battles in Korea, and many temples were built. In the 7th century, Shotoku Taishi and Soga Umako edited the Tennoki and the Kokki, but these documents, and others of that time, were burned in the Taika Reforms of 646. The Yamato Government continued to interfere in Korea, until its major defeat at Paekchon River in 663. And a few decades after that, true history dawned in Japan.” [Source: Charles T. Keally, Professor of Archaeology and Anthropology (retired), Sophia University, Tokyo, t-net.ne.jp/~keally/kofun ++]

Kofun Period Imperial Rulers (ca. 3rd century–538 A.D.)

Ojin (A.D. 270-310 in the Nihon Shoki, probably real, ca. 370-390 or early 5th century).

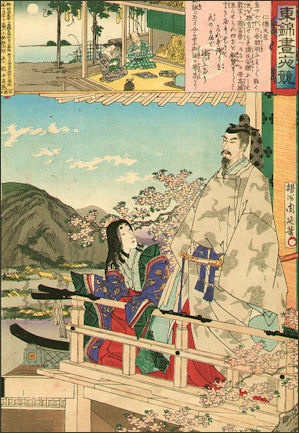

Emperor Nintoku

Nintoku (A.D. 313-399 in the Nihon Shoki,actual early 5th century).

Ritchu (A.D. 400-405 in the Nihon Shoki, actual early 5th century).

Hanzei (A.D. 406-410 in the Nihon Shoki, actual early 5th century).

Ingyo (A.D. 412-453 in the Nihon Shoki, actual early 5th century).

Anko (A.D. 453-456 in the Nihon Shoki, actual mid 5th century) .

Yuryaku (456-479 in the Nihon Shoki, probably correct).

Seinei (480-484 in the Nihon Shoki, probably correct).

Kenzo (485-487 in the Nihon Shoki, probably correct).

Ninken (488-498 in the Nihon Shoki, probably correct).

Buretsu (498-506 in the Nihon Shoki, probably correct).

Keitai (507-531 in the Nihon Shoki, probably correct).

Ankan (531-535 in the Nihon Shoki, probably correct).

Senka (535-539 in the Nihon Shoki, probably correct). [Source: Charles T. Keally, Professor of Archaeology and Anthropology (retired), Sophia University, Tokyo, t-net.ne.jp/~keally/kofun , The Nihon Shoki is an ancient history record finished in A.D. 720]

Major Events the Kofun Period

Early Kofun: A) 266-413: no Chinese documents on events in Japan; B) 300: mound tombs common in Kinki and coastal Seto Naikai; C) 391: Wa defeats Paekche and Silla, and battles with Koguryo. [Source: Charles T. Keally, Professor of Archaeology and Anthropology (retired), Sophia University, Tokyo, t-net.ne.jp/~keally/kofun ++]

Middle Kofun: A) 413-502: the "mysterious" five kings of Wa — San, Chin, Sei, Kou and Bu — send regular emissaries to China; B) 430s: massive kofun being built everywhere; C) 471: writing on iron sword in the Inariyama Kofun in Saitama Pref., saying that the nation was already unified; D) 470s: groups of small kofun appear in Kinki.

Late Kofun: 540: the first register of immigrants was made.

Archeology of the Kofun Period

Keally wrote: “Archaeology focuses strongly on the mound tombs that mark the period. It also deals with the pottery, buildings, villages and towns, and production and trade. The tombs are studied from every angle -- structure and size, burial goods, haniwa, funeral rituals, implications for social structure, role of Imperial Family, and so on. The pottery is studied largely for production techniques and as time markers. The buildings and the villages and towns are studied to learn about the lifeways of the people. And production and trade are studied to learn about the economy of the time. Rice farming was established as the economic base in the previous period, and no significant new items are known to have been added during the Kofun Period, so the Kofun diet gets relatively little attention from archaeologists. ++

“The first excavation of a mound tomb in Japan was conducted by Mito (Tokugawa) Mitsukuni in 1692, the 5th year of the Genroku era. Mitsukuni (1628-1701) was the grandson of Tokugawa Ieyasu, founder of the Tokugawa Shogunate. The tomb he excavated is called the Samuraizuka Kofun, located in Ohtawara City, Tochigi Prefecture, just north of Tokyo. This excavation is considered the first academic, or scientific, excavation conducted in Japan. “ ++

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Aileen Kawagoe, Heritage of Japan website, heritageofjapan.wordpress.com ; Charles T. Keally, Professor of Archaeology and Anthropology (retired), Sophia University, Tokyo ++; Topics in Japanese Cultural History” by Gregory Smits, Penn State University figal-sensei.org ~; Asia for Educators Columbia University, Primary Sources with DBQs, afe.easia.columbia.edu ; Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Japan; Library of Congress; Japan National Tourist Organization (JNTO); New York Times; Washington Post; Los Angeles Times; Daily Yomiuri; Japan News; Times of London; National Geographic; The New Yorker; Reuters; Associated Press; Lonely Planet Guides; Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications. Many sources are cited at the end of the facts for which they are used.

Last updated September 2016