YAMATO

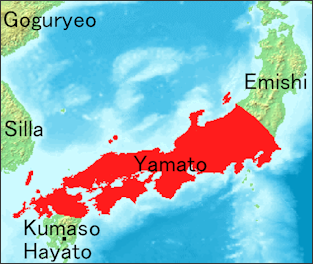

Over time the warring states of Japan unified. The Yamato polity, which would dominate Japan for centuries to come, emerged by the late fifth century. It was distinguished by powerful great clans or extended families, including their dependents. Each clan was headed by a patriarch who performed sacred rites to the clan’s kami to ensure the long-term welfare of the clan. Clan members were the aristocracy, and the kingly line that controlled the Yamato court was at its pinnacle. The Yamato conquered the Yamato plain (now in Nara prefecture) around A.D. 300 by an alliance of clans that evolved into the Yamato kingdom. This is the first period when Japan was regarded as a unified entity. [Source: Library of Congress]

The state of Yamato was the nucleus of modern Japan. Charles T. Keally wrote: “One major question in Yayoi archaeology and in Japanese history is what exactly this Yamatai-koku was politically. The Wei Records report that this "nation" was ruled by a woman named Himeko, that it sent envoys to China, and that it was engaged in battles with some of its neighbors, some of the "100 nations in the land of Wa" (Japan). This question is a long way from solution. Empress Jingu in the Nihon Shoki records, written in the early 8th century, is probably the Chinese "Himeko" in the Japanese mythology. [Source: Charles T. Keally, Professor of Archaeology and Anthropology (retired), Sophia University, Tokyo, net.ne.jp/~keally/yayoi]

On the origin of the of the term, Yamato, Anesaki writes: “The etymology of the word Yamato is disputed. According to the commonly accepted theory it means “Mountain-gateways,” because the region is surrounded by mountains on all sides and opens through a few passages to the regions beyond the mountain ranges. This seems to be a plausible interpretation, because it is most natural to the Japanese language. But it is a puzzling fact that the name is written in Chinese ideograms which mean “great peace.” However, the ideogram meaning “peace” seems to have been used simply for the Chinese appellation of the Japanese “wa,” which, designated in another letter, seems to have meant “dwarf.” Chamberlain’s theory is that Yamato was Ainu in origin and meant “Chestnut and ponds.” But this is improbable when we take into account the fact that the ponds, numerous in the region, are later works for irrigation.

Websites: Yamato Period Wikipedia article on the Yamato period Wikipedia article ; Kojiki, Nihongi and Sacred Shinto Texts sacred-texts.com ; Imperial Household Agency kunaicho.go.jp/eindexList of Emperors of Japan friesian.com ; Buddhism and Prince Shotoku onmarkproductions.com ; Essay on the Japanese Missions to Tang China aboutjapan.japansociety.org . References: 1) The Chronicles of Wa, Gishiwajinden by Wes Injerd; 2) Wa (Japan), Wikipedia; 3) Excerpts from the History of the Kingdom of Wei, Columbia University’s Primary Source Document Asia for Educators. Asuka Wikipedia article on Asuka Wikipedia ; Asuka Park asuka-park.go.jp ; Asuka Historical Museum asukanet.gr.jp ; UNESCO World Heritage sites ; Early Japanese History Websites: Aileen Kawagoe, Heritage of Japan website, heritageofjapan.wordpress.com; Essay on Early Japan aboutjapan.japansociety.org ; Japanese Archeology www.t-net.ne.jp/~keally/index.htm ; Ancient Japan Links on Archeolink archaeolink.com ;Essay on Rice and History aboutjapan.japansociety.org ; Metropolitan Museum of Art Department of Asian Art metmuseum.org; Wikipedia article on the Jomon Wikipedia ; Historical Parks Sannai Maruyama Jomon Site in Northern Honshu sannaimaruyama.pref.aomori.jp ; Yoshinogari Historical Park yoshinogari.jp/en ;Good Photos of Jomon, Yayoi and Kofun Sites at Japan-Photo Archive japan-photo.de ; Wikipedia article on the Ainu Wikipedia ; Good Japanese History Websites: ; Wikipedia article on History of Japan Wikipedia ; Samurai Archives samurai-archives.com ; National Museum of Japanese History rekihaku.ac.jp ; English Translations of Important Historical Documents hi.u-tokyo.ac.jp/iriki

RELATED ARTICLES IN THIS WEBSITE: ANCIENT HISTORY factsanddetails.com; YAYOI PERIOD (400 B.C.– A.D. 300) factsanddetails.com; YAYOI PERIOD AND THE ORIGIN OF MODERN JAPANESE PEOPLE factsanddetails.com; YAYOI PEOPLE, LIFE, AND CULTURE (400 B.C.-A.D. 300) factsanddetails.com; YAYOI METALLURGY factsanddetails.com; YAYOI RELIGION AND BURIALS factsanddetails.com; RICE AGRICULTURE IN THE YAYOI PERIOD factsanddetails.com; FIRST CROPS AND EARLY AGRICULTURE AND DOMESTICATED ANIMALS IN CHINA factsanddetails.com; WORLD'S OLDEST RICE AND EARLY RICE AGRICULTURE IN CHINA factsanddetails.com; WA AND EARLY CONTACTS BETWEEN CHINA AND JAPAN actsanddetails.com; MYTHICAL ORIGINS OF JAPAN, THE JAPANESE AND THE JAPANESE EMPEROR factsanddetails.com KOFUN PERIOD (A.D. 3RD CENTURY–538) factsanddetails.com; KOFUN PERIOD, CLANS AND EARLY YAMATO RULERS factsanddetails.com; KOFUN RELIGION factsanddetails.com; KOFUN PEOPLE AND LIFE (A.D. 3RD CENTURY–538) factsanddetails.com; KOFUN PERIOD (A.D. 3RD CENTURY–538) KOFUN AND TOMBS factsanddetails.com; KOFUN-ERA JAPAN, CHINA AND KOREA: RELATIONS, INFLUENCES AND TRADE factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: “Japan in Five Ancient Chinese Chronicles: Wo, the Land of Yamatai, and Queen Himiko” by Massimo Soumaré, Mark Hall, et al. Amazon.com; “Himiko and Japan's Elusive Chiefdom of Yamatai: Archaeology, History, and Mythology” by J. Edward Kidder Jr Amazon.com; “Reading the Treatise on the People of the Wa in the Chronicle of the Kingdom of Wei”: The World’s Earliest Written Text on Japan by Arikyo Saeiki and Joshua A. Fogel (2018) Amazon.com; “Paekche of Korea and the Origin of Yamato Japan” (Ancient Korean-Japanese History) by Wontack Hong Amazon.com; “The Archaeology of Japan: From the Earliest Rice Farming Villages to the Rise of the State (Cambridge World Archaeology)” by Koji Mizoguchi Amazon.com; “An Illustrated Companion to Japanese Archaeology (Comparative and Global Perspectives on Japanese Archaeology)” by Werner Steinhaus, Simon Kaner, et al. (2020) Amazon.com; “Life In Ancient Japan” by Hazel Richardson Amazon.com; “Daily Life and Demographics in Ancient Japan” (Michigan Monograph Series in Japanese Studies) (2009) by William W Farris Amazon.com; “Archaeology of East Asia: The Rise of Civilisation in China, Korea and Japan” by Gina L. Barnes Amazon.com; “The Role of Contact in the Origins of the Japanese and Korean Languages” by J. Marshall Unger 2008 Amazon.com; “The Cambridge History of Japan, Vol. 1: Ancient Japan” (Volume 1) by Delmer M. Brown Amazon.com

Rise of the Solar Uji and the Nakatomi/Fujiwara

Fujiwara Clam emblem

According to “Topics in Japanese Cultural History”: As its name implies, this uji claimed descent from the sun (or its equivalent, the solar deity Amaterasu). Archaeological evidence strongly suggests that this uji changed its alleged ancestor several times in the distant past, but by the sixth century, if not earlier, it was claiming descent from the sun, a claim that continued into modern times. Did the other powerful uji allied with it believe this claim of solar descent? It is hard to say with certainty, but they did seem to recognize the superiority of the solar uji, at least in theory. In practice, however, there were numerous occasions when theoretically subordinate allied uji threatened to usurp the solar uji’s superior position. An uji with the name Soga, for example, came very close to eliminating and replacing the solar uji during the early 600s. With assistance of members of other, non-Soga uji who also felt threatened by the powerful Soga, leading members of the solar uji launched a violent attack on the Soga in 645, killing its leaders. [Source: “Topics in Japanese Cultural History” by Gregory Smits, Penn State University figal-sensei.org ~]

“To consolidate its victory, the solar uji declared its head "emperor" of the Japanese islands. So it is only from this time that most of the Japanese islands came under the control of a centrally-located monarch--at least in name. So now let us change its name from solar uji to imperial clan or imperial family. In fact, however, the newly-named imperial clan lacked the military power to enforce its claims of emperorship at this time. As before, it had to rely on the backing of its allies. The major difference was that instead of the Soga uji, it was an uji called Nakatomi that now wielded the predominance of power in the confederation. In 669, the head of the imperial clan granted the Nakatomi a new name in honor of their service. Henceforth, this powerful uji was called Fujiwara. As we will see, although requiring two centuries to accomplish, the Fujiwara eventually usurped most of the power of the imperial clan. But they learned from the Soga’s fate and never sought to call themselves emperors or to take over the emperor’s position directly. Instead, they ruled from behind the scenes and preferred marriage politics to the politics of military force--but we are getting ahead of ourselves. ~

Returning to the late seventh century, even with Fujiwara support, the new imperial clan lacked the military power necessary for it to rule in both name and in fact as a central monarch. This situation changed in 673 when Tenmu (r. 673-686) came to the throne as emperor. Though a member of the imperial family, Tenmu was not the legitimate heir to the throne. He took over the throne by force, which may have been a good thing for the imperial family in hindsight. The reason?--Tenmu possessed significant military force in the form of soldiers loyal to him. With this force, he was able to make himself emperor both in name and in fact. Tenmu sought to bolster his own legitimacy on the throne and the legitimacy of the imperial family as emperors of the Japanese islands. He and his immediate successors went about this task along three main routes. First, they sought to re-organize the institutions of central government, a process that was not complete until the first decade of the eight century. Second, they sought to enhance their symbolic authority by re-organizing titles of nobility, rites and rituals, and, especially, by embracing and using Buddhism--a topic we explore later. Finally, Tenmu initiated the writing of two official histories, which were not completed until well into the with century. These official histories, Record of Ancient Matters (Kojiki, 712 ) and Chronicles of Japan (Nihongi, 720, also known as Nihonshoki). Not surprisingly, these official histories present narratives that legitimize the imperial family as the rightful, natural, heavenly-ordained rulers of the Japanese islands. The other powerful uji are also presented as having a rightful place in the order of things, albeit below that of the imperial family.” ~

Location of Yamato

Yoshinogari, the center of Yamato?

The location of the original Yamataokoku kingdom is a matter of dispute. Some think it was in northern Kyushu; others believe it was in the Kinki (Osaka, Kyoto, Nara) area. Many think it arose around modern-day Nara and Osaka and spread as far as Kyushu by the A.D. forth century.

Kevin Short wrote in the Daily Yomiuri: “Early Chinese historical sources, unfortunately, provide little insight as to where the Japanese state developed. The first source to offer detailed information on Japan, an historical document called the Wajinden, or “Account of the Wa”, was compile in th year 280, and was based n diplomatic missions sent by the Chinese government several decades earlier. The envoys reported visiting a kingdom known as Yamatikoku, ruled by a shamanese queen named Himiko. The account notes that the people of this kingdom were wet rice farmers using iron and silk, but not keeping domestic cattle or sheep, Himiko lived in a substantial palace, and assumed the throne after a long period of civil war. [Source: Kevin Short, Daily Yomiuri, February 2010]

“The problem with the Chinese account is that there is no firm information on where Yamatikoku was located. “Based on various interpretations no less than 10 sites, including one in northern Honshu, have been proposed as location sites. Most scholars narrow the candidates down to two contenders: Kyushu and the southern Nara basin. Proponents of the Kyushu theory lace Himiko’s palace in eastern Saga Prefecture at the expansive archeological site of Yoshinogari. Unfortunately for the Kyushu supporters, the discovery in 2009 of even more extensive remains at the Makimuku site in Nara has made that area the current favorite.”

Keally wrote: “The other major question is the location of Yamatai-koku. Over 50 different locations have been proposed, but the majority are either in northwestern Kyushu or in Kansai. Archaeological evidence is used extensively to support both hypotheses, and new archaeological finds bring new changes into the arguments every year. But the crux of the controversy is the directions and distances to Yamatai-koku reported in the Wei Records. Following these directions and distances simplistically and consecutively on today’s map leads you out into the Pacific Ocean. Thus some archaeologists and historians argue that the directions and distances should not be followed consecutively, but rather separately from the same landing point in northwestern Kyushu. This places Yamatai-koku also somewhere in northern Kyushu. But if the directions and distances are followed consecutively following an ancient Chinese map, they lead to the Kansai area, since the ancient Chinese map of Japan is oriented roughly 90 degrees off of today’s map. Most scholars seem to ignore the ancient Chinese map in their arguments. This controversy seems to have a lively future yet.” [Source: Charles T. Keally, Professor of Archaeology and Anthropology (retired), Sophia University, Tokyo, net.ne.jp/~keally/yayoi]

Yamato-State in Nara

Pottery from Makimuku

Around the 4th century the Yamoto state was established in the area around present-day Nara. In those days the emperor depended on the support of powerful clans. At first he was supported by the Shinto-believing Mononobe clan. But after a fierce series of battles the Mononobe clan was ousted by the Buddhist-believing Sogo clan, paving the way for flowering of Buddhism in Japan. Trade with the various kingdoms in Korea in the 4th century brought the industrial arts of weaving, metalworking, tanning and shipbuilding to Japan.

Mononobe, a military clan, were set on maintaining their prerogatives and resisted the alien religious influence of Buddhism. The Soga introduced Chinese-modeled fiscal policies, established the first national treasury, and considered the Korean Peninsula a trade route rather than an object of territorial expansion. Acrimony continued between the Soga and the Nakatomi and Mononobe clans for more than a century, during which the Soga temporarily emerged ascendant.

The Makimuku ruins at the foot Miwa in Sakurao in Nara Prefecture are believed to be the site of Japan’s first true city. A major excavation for the site has been approved, The city was as its height in the A.D. 3rd century and is thought to contain important evidence on early exchanges between China and Japan. Study of teh site may help locate of the seat of the Yamataikoku kingdom, the predecessor of the Yamato state.

Yamato Government and Court Life

Keally wrote: “The Yamato Government was centered on a Kimi (King), and from the 5th century an Ohkimi (Great King).The title Tenno (Emperor) was used from the time of Temmu (673-686). The government was a coalition of Great Clans. These were the Soga, Kazuraki, Hekuri, Wada and Koze clans in the Nara Basin, and the Izumo and Kibi clans in the Izumo-Hyogo area. The Ohtomo and Mononobe clans were the military leaders, and the Nakatomi and Inbe clans handled rituals. The Soga clan provided the highest minister in the government, while the Ohtomo and Mononobe clans provided the second highest ministers. The heads of provinces were called Kuni-no-miyatsuko. The crafts were organized into guilds. But this whole organization evolved throughout the period; the details are in most history books. [Source: Charles T. Keally, Professor of Archaeology and Anthropology (retired), Sophia University, Tokyo, t-net.ne.jp/~keally/kofun ++]

Text of the Wei Zhi

Wang Chong’s Lunheng “Discourses Weighed in the Balance” (A.D. 70-80) is an ancient compendium of essays on subjects including philosophy, religion, and natural sciences. The Ruzeng “Exaggerations of the Literati” chapter mentions ”Warén “Japanese people” and Yuèshang “an old name for Champa” presenting tributes during the Zhou Dynasty. In disputing legends that ancient Zhou bronze ding tripods had magic powers to ward off evil spirits, Wang says, “During the Chou time there was universal peace. The Yuèshang offered white pheasants to the court, the Japanese odoriferous plants. Since by eating these white pheasants or odoriferous plants one cannot keep free from evil influences, why should vessels like bronze tripods have such a power. (26, tr. Forke 1907:505) Another Lunheng chapter Huiguo “Restoring the nation” (58) similarly records that Emperor Cheng of Han (r. 51-7 B.C.) was presented tributes of Vietnamese pheasants and Japanese herbs.[Source: Aileen Kawagoe, Heritage of Japan website, heritageofjapan.wordpress.com ]

One Wei Zhi passage (A.D. 220-265, tr. Tsunoda 1951:14) describes “Grandees” translates Chinese dàfu (lit. “great man”) “senior official; statesman” (cf. modern dàifu “physician; doctor”), which mistranslates Japanese imperial taifu “5th-rank courtier; head of administrative department; grand tutor” (the Nihongi records that the envoy Imoko was a taifu).

Yamato Kingdom Stretched Further North Than Previously Thought

In 2012, it was reported that the political and cultural influence of the ancient Yamato kingdom reached about 250 kilometers farther north than previously believed, a new archaeological find in Niigata Prefecture has revealed. The Yomiuri Shimbun reported the board of education of Tainai, Niigata Prefecture, excavated a bronze mirror, magatama beads, a piece of lacquerware and other burial-related items from an ancient Jonoyama burial mound dating back to the first half of the fourth century. The excavated items strongly resemble other pieces found mainly in the Kinki region, where the Yamato kingdom was based. [Source: Yomiuri Shimbun, September 17, 2012]

Until recently, the reigning belief among scholars was that the northern extent of the Yamato kingdom’s influence was the Noto Peninsula on the Sea of Japan, due to the large number of similar burial items found in several locations. The latest find is about 250 kilometers farther north of that.

The round mound stretches about 35 meters north to south, about 40 meters east to west, and is about five meters high, according to the board of education. The burial mound is one of the northernmost on the Sea of Japan among those built in the first half of the Kofun period (ca 300-ca 710). A wooden coffin found in the mound had almost completely decayed, but researchers determined it was boat-shaped, about eight meters long, about 1.5 meters wide, and decorated with red pigment. There is no evidence the mound had been plundered by grave robbers, as a wide variety of items were found inside, including the bronze mirror, magatama beads, a sword and a bow. A lacquered "yuki" box more than 80 centimeters long that was used to store arrows was found in good condition. The box is similar to one excavated from the Yukinoyama Kofun burial mound in Higashiomi, Shiga Prefecture.

"I believe the yuki box and other craftwork items were made in the central Kinki region and brought to the site," said Niigata University Prof. Hirofumi Hashimoto, the archaeologist who led the excavation of the Jonoyama mound. "These precious findings prove the Yamato kingdom’s influence reached the Tohoku region.”

Yamato-era kofun

Japan Arrived Later than Some Think

Gina Barnes of Durham University has challenged prevailing views on Kofun Period and the development of the Japanese state. She argues that the first Japanese state emerged in the fifth century, not two centuries earlier as many scholars have said. “We have a many-staged effort within the Japanese sequence, which is not unilineal and not teleological—not headed toward a political state that the Japanese would like to believe had existed from early on and still supplies their imperial rule today,” Barnes said. [Source: Gina Barnes, Professor Emeritus and Honorary Research Fellow, Durham University and Professorial Research Associate, School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London, UCLA Asia Institute, December 3, 2007. Barnes is the author of “State Formation in Japan: Emergence of a 4th-century Ruling Elite” (Routledge, 2007). ~~]

Vincent Lim of UCLA Asia Institute, “Historical records from the Kofun period are hard to decipher without knowledge of archaeology. Some archaeologists say the record, including Chinese sources, indicates that various communities and chiefdoms began developing into states around the end of the third century, when large tombs began appearing. Barnes said her research challenged prevailing notions of Japanese state development. She explained how triangular-rimmed bronze mirrors found in the tombs were shared among elites from different polities, but not in a way that would suggest a hierarchical relationship. Passages from the Nihon Shoki, one of the oldest written sources used by Japanese historians, illuminate how goods like triangular-rimmed bronze mirrors were used in elite identification. The mirrors seemed to be used to create social and political alliances among elites, not to demand allegiance. There was no clear hierarchical relationship among communities in the Early Kofun period, said Barnes. ~~

“According to Barnes, there was no clear polity formation in terms of the usual hierarchical size and rank distribution in the society until the mid-fourth century when the Early Kofun system actually began to collapse. It was not until the late fifth century that Japan had a state or an administrative political unit. She further said that even in the fifth century, the Japanese state included Osaka, Nara and Kyoto, but left out much of western and eastern Japan. The Kofun period marked a time when there was social stratification—when elites began sharing a similar culture and system separate from commoners—but it did not mark the beginning of the Japanese state, according to Barnes. ~~

“Barnes also explained how recent research suggests that there was more contact between China and western Japan during the period than thought. She explained how the symbolism of the Queen Mother of the West, which comes from Chinese mythology and Taoism, appeared in Early Kofun tombs.

mapping of a kofun

The Queen Mother of the West was associated with jade, carried a staff and was supposed to hold grand, divine feasts. Jade substitutes—staffs and drinking cups made of jasper and green tuff—were found in Japanese tombs of the time. “Japanese archaeologists and I myself had always thought [mounded-tomb culture] was an indigenous development with these localized artifacts that don’t occur in China,” Barnes said. “Now all of a sudden, they take on a completely different significance as emblems of a Queen Mother cult in the Early Kofun.” ~~

Yamato Keyhole Tombs

Gigantic earthen burial mounds known as kofun (tumuli) first were built for important people and they were usually surrounded by a moat. The came in different shapes---round-, square- and keyhole-shaped---and were similar to graves found in China and Korea. There in which these tombs were found is sometimes designated as a historical period, the Kofun Period (A.D. 300-710)

The largest tombs were keyhole-shaped. Some covered four or five acres. They first appeared in the Yamato region in the late 3rd and early 4th centuries A.D. and spread to northern Honshu and southern Kyushu by the end of the 4th century. The spread of these tombs is offered as proof of the spread of Yamato culture.

Inside excavated tombs archaeologists have found mirrors, swords, armor, earrings, bracelets, equestrian gear, crowns, shoes, terra cotta figures, and personal ornaments made from precious beads and worked gold and copper. The ancient Japanese, like their Chinese counterparts, probably believed they could take these objects with them to the next life. Earthenware cylinders, haniwa clay figures, and sculptures, some as tall as 1½ meters, surrounded the kofuns.

Archeologist have not had a chance to excavate the largest and most important keyhole tombs (believed to hold the remains of ancient emperors and their families) because the tombs are regarded as sacred and inviolable and thus should be left undisturbed.

Queen Himiko

The legendary ruler Queen Himiko governed the Yamataokoku kingdom from the end of the second century and died around A.D. 248 according to an ancient Chinese history text. A 280-meter-long keyhole tomb in Sakurai in Nara that has been dated to A.D. 240 to 260 is thought to belong her. The tomb is thought to have taken ten years to make, with construction beginning while the queen was still alive.

1988 painting ofHimiko

Kawagoe wrote: Queen Himiko was the queen of Yamatai kingdom or “country” (or state) who symbolized the unity of the Yayoi people. Queen Himiko may have held the ceremonial role of a shaman priestess, prophetess or perhaps, a pre-eminent shrine maiden with proxy access to the gods for the people. Gishi no Wajinden described her as a having “occupied herself with magic and sorcery, bewitching the people”. Shrouded in mystery, Queen Himiko was said to have controlled the kingdoms by sorcery and magic. She was seldom seen in public and was attended by “one thousand attendants, but only one man”. [Source: Aileen Kawagoe, Heritage of Japan website, heritageofjapan.wordpress.com]

“Although Queen Himiko left the execution of the affairs of state to her younger brother, Queen Himiko very likely held actual power in addition to her ceremonial and religious role. She was guarded by a large army and the Chinese thought of her as a ruler with extraordinary power. Yamatai kingdom prospered under Queen Himiko’s rule and was observed in the Gishi no Wajinden records to have had more than seventy thousand households, well-organized laws and taxation system and thriving trade. Her people were noted to have been mainly gentle and peace-loving.”

“When Queen Himiko died, her people constructed a large burial mound (about 100 meters in diameter) for her. One thousand female and male attendants were sacrificed for burial along with their queen. She had lived between A.D. 183 and 248 without having ever married. Upon her death, the male ruler who took her place did not last long and the chiefdoms fell into disunity and fighting. “Assassination and murder followed; more than one thousand were thus slain” according to Gishi no Wajinden. When Iyo, a 13-year old girl related to Himiko was placed on the throne, peace was restored and the fighting ended. The location of Yamatai kingdom (as well as that of the burial mound of Queen Himiko) remains a mystery and is the subject of a huge academic controversy as to whether northern Kyushu or Kinai had been the actual headquarters of Queen Himiko.

Sources and references: In the news: 1) Dig in Nara, not Kyushu, yields palatial ruins possibly of Himiko (Japan Times, Nov 12, 2009); 2) Himiko and Japan’s Elusive Chiefdom of Yamatai: Archaeology, History and Mythology by J. Edward Kidder, Jr.

“History of the Kingdom of Wei” Account of Himiko

Text of the Wei Zhi

According to Columbia University’s Asia for Educators: The discussion of early Japanese society and government in the Chinese chronicle “History of the Kingdom of Wei (Wei Zhi)” [A.D. 297] “ is particularly noteworthy for its focus on Pimiko (also known as Himiko), the “Queen of Wa.” Since Pimiko does not appear in indigenous Japanese records of the nation’s early history, the identity and the very existence of Pimiko have long been subjects of active debate among historians. It is interesting to note that, although Japanese law today forbids a woman from becoming emperor, there is a long tradition of female rulers in Japan, stretching back to the controversial Pimiko.” [Source:Asia for Educators Columbia University, Primary Sources with DBQs, afe.easia.columbia.edu ]

According to the Chinese chronicle “History of the Kingdom of Wei”: The country formerly had a man as ruler. For some seventy or eighty years after that there were disturbances and warfare. Thereupon the people agreed upon a woman for their ruler. Her name was Pimiko. She occupied herself with magic and sorcery, bewitching the people. Though mature in age, she remained unmarried. She had a younger brother who assisted her in ruling the country. After she became the ruler, there were few who saw her. She had one thousand women as attendants, but only one man. He served her food and drink and acted as a medium of communication. She resided in a palace surrounded by towers and stockades, with armed guards in a state of constant vigilance. [Source: Adapted from Tsunoda and Goodrich, Japan in the Chinese Dynastic Histories, pp. 8.16, “Sources of Japanese Tradition, compiled by Wm. Theodore de Bary, Donald Keene, George Tanabe, and Paul Varley, 2nd ed., vol. 1 (New York: Columbia University Press, 2001), 6-8; Asia for Educators Columbia University, Primary Sources with DBQs, afe.easia.columbia.edu ]

“When Pimiko passed away, a great mound was raised, more than a hundred paces in diameter. Over a hundred male and female attendants followed her to the grave. Then a king was placed on the throne, but the people would not obey him. Assassination and murder followed; more than one thousand were thus slain.

“A relative of Pimiko named Iyo, a girl of thirteen, was [then] made queen and order was restored. Zheng [the Chinese ambassador] issued a proclamation to the effect that Iyo was the ruler. Then Iyo sent a delegation of twenty under the grandee Yazaku, General of the Imperial Guard, to accompany Zheng home [to China]. The delegation visited the capital and presented thirty male and female slaves. It also offered to the court five thousand white gems and two pieces of carved jade, as well as twenty pieces of brocade with variegated designs. “

Chinese Accounts of Queen Himiko’s Diplomatic Mission to China

rendering of Himiko

Queen Himiko was known to the Chinese because her government had sent a diplomatic mission in the year A.D. 238 to the Wei emperor, Cao Rui’s court, and the delegation was received as presenting tribute to the Chinese emperor. [Source: “Topics in Japanese Cultural History” by Gregory Smits, Penn State University figal-sensei.org ~]

According to the Chinese chronicle “History of the Kingdom of Wei”: “In the sixth month of the second year of Jingchu [238 C.E.], the Queen of Wa sent the grandee Nashonmi and others to visit the prefecture [of Daifang], where they requested permission to proceed to the Emperor’s court with tribute. The Governor, Liu Xia, dispatchedan officer to accompany the party to the capital. [Source: Adapted from Tsunoda and Goodrich, Japan in the Chinese Dynastic Histories, pp. 8.16, “Sources of Japanese Tradition, compiled by Wm. Theodore de Bary, Donald Keene, George Tanabe, and Paul Varley, 2nd ed., vol. 1 (New York: Columbia University Press, 2001), 6-8; Asia for Educators Columbia University, Primary Sources with DBQs, afe.easia.columbia.edu ]

Queen Himiko was recognized as the ruler of Wa : “Herein we address Himiko (Pimiko is used), Queen of Wa, whom we now officially call a friend of Wei … [Your ambassadors] have arrived here with your tribute, consisting of four male slaves and six female slaves, together with two pieces of cloth with designs, each twenty feet in length. You live very far away across the sea; yet you have sent an embassy with tribute. Your loyalty and filial piety we appreciate exceedingly. We confer upon you, therefore, the title “Queen of Wa Friendly to Wei”.” [Source: Aileen Kawagoe, Heritage of Japan website, heritageofjapan.wordpress.com ]

In 238, Himiko sent a diplomatic envoy to the court of Cao Rui, the Wei emperor in China. According to the “History of the Kingdom of Wei”: Herein we address Pimiko, Queen of Wa, whom we now officially call a friend of Wei. The Governor of Daifang, Liu Xia, has sent a messenger to accompany your vassal, Nashonmi, and his lieutenant, Tsushi Gori. They have arrived here with your tribute, consisting of four male slaves and six female slaves, together with two pieces of cloth with designs, each twenty feet in length. You live very far away across the sea; yet you have sent an embassy with tribute. Your loyalty and filial piety we appreciate exceedingly. We confer upon you, therefore, the title “Queen of Wa Friendly to Wei,” together with the decoration of the gold seal with purple ribbon. The latter, properly encased, is to be sent to you through the Governor. We expect you, O Queen, to rule your people in peace and to endeavor to be devoted and obedient.” In return, Cao Rui in return sent Himiko the gift of one hundred bronze mirrors, and there were subsequent visits of emissaries between the two kingdoms.

…

The Wajinden also alludes to how Himiko ruled: “High [ranking] Wa are sent to inspect [the trade of the different kuni]. A high leader was especially sent to to the region] north of the queen’s land. He inspects all the kuni there. Regularly he rules in Ito.” According to to Kawagoe: “Thus Ito held an important role in international relations. During her reign, Queen Himiko sent envoys to Gi to limit the influence of a rival power, the “king” of Kunu whose country of Kuna (Kuna no Koku) lay to the south of Wa. In 239 A.D., an emperor of Gi granted the Yamatai kingdom a honorable title “Sin Gi Wa O” along with a gift of 100 bronze mirrors. By 247 A.D. Queen Himiko’s realm and that of the country of Kuna were at odds, but the outcome of that conflict is not known, only that she sought Chinese imperial support and that she died likely in the year following that.”

Queen Himiko’s Tomb

Himiko's tomb

In 2009, Japanese archaeologists said they believed they had identified the tomb of Queen Himiko, but are unlikely to ever have conclusive proof as they are forbidden from further excavation of the site by the Imperial Household Agency (The bureaucracy of the Japanese Emperor). [Source: Julian Ryall, The Telegraph, April 1, 2009 ]

Julian Ryall wrote in The Telegraph, “Researchers from the National Museum of Japanese History presented a paper to the 75th annual meeting of the Japanese Archaeological Association, claiming that evidence points to a burial mound in the town of Sakurai, near the ancient capital of Nara in central Japan, as the tomb of Queen Himiko. Archaeologists had previously claimed that the tomb, built in the traditional keyhole-shape design, was built in the fourth century and therefore too modern for Queen Himiko. The tomb, at 280 metres long, is nearly three times the size of other burial mounds in the region. “She is a very important part of Japanese history as she was the first queen, ruled for many years – although we do not know exactly how long – and has gone down in history as a very popular ruler,” said Professor Harunari.

“Prof Harunari’s paper is likely to provoke new debate over Japanese history and the royal family, which the Imperial Household Agency still claims is descended from the mythical sun goddess Amaterasu. One of the biggest question marks remains over whether Himiko was a queen or more of a shaman. Excavation of the tomb could settle that debate once and for all, although the Imperial Household Agency appear to have ruled that out. “I would love to be able to excavate the tomb, but it is impossible to get permission because the agency says that our present emperor is descended from Queen Himiko,” said Professor Harunari. “But I still believe the evidence fits and this is her tomb.”

In November 2009, a 19.2-meter-long structure was found in Sakurai, Nara Prefecture. The building was so large that archeologist speculated that it may have been a palace of the female ruler in the ancient state of Yamataikoku, which some think was in Nara and others believe was in Kyushu. The ruins lie near Hashihaka tomb, the oldest keyhole tomb in Japan. The tomb is believed to belong to Himiko and may have been the birthplace of the Yamato Kingdom.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, Himiko tomb: from "A Blog About History"

Text Sources: Aileen Kawagoe, Heritage of Japan website, heritageofjapan.wordpress.com ; Charles T. Keally, Professor of Archaeology and Anthropology (retired), Sophia University, Tokyo ++; Topics in Japanese Cultural History” by Gregory Smits, Penn State University figal-sensei.org ~; Asia for Educators Columbia University, Primary Sources with DBQs, afe.easia.columbia.edu ; Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Japan; Library of Congress; Japan National Tourist Organization (JNTO); New York Times; Washington Post; Los Angeles Times; Daily Yomiuri; Japan News; Times of London; National Geographic; The New Yorker; Reuters; Associated Press; Lonely Planet Guides; Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications. Many sources are cited at the end of the facts for which they are used.

Last updated September 2016