FALSE GHARIALS

False gharial (Tomistoma schlegelii) are also known as Malayan gharials, false gavials and Sunda gavials. They are freshwater crocodiles native to the Malay Peninsula, Borneo and Sumatra with very thin and elongated snouts like gharials. Based morphology, they were originally placed within the family Crocodylidae (crocodiles), but recent immunological studies suggest that it is more closely related to gharials than was originally thought. False gharial are listed as an endangered species by IUCN with a population estimated to be below 2,500 mature individuals. [Source: Wikipedia]

There is still a debate over taxonomic classification of false gharials. They were listed in the family Crocodylidae based on fossil evidence and morphological similarities to extant crocodiles. Recently they have been placed in the family Gavialidae with ghavials based on biochemical, immunological and molecular characteristics. Gavialidae is made of only two orders each with one species: Genus Gavialis (with gharials as its one species) and Tomistoma (with false gharials as its one species). Genetic studies suggest that tomistomine and gavialine crocodilians should be placed into one taxon, which would comprise a sister group to the Crocodylidae. Other crocodilian researchers suggest considering Tomistominae and Gavialinae as sister taxa. [Source: Katie Foster, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

False gharials have an estimated lifespan in the wild of 60 to 80 years, similar to that of other crocodilians. Reports indicate that captive specimens have a shorter lifespan. Adult false gharials are not really threatened by any natural predator because of their large size but eggs and hatchlings preyed upon by wild pigs and and large reptiles, such as monitor lizards.

RELATED ARTICLES:

CROCODILES: CHARACTERISTICS, ANATOMY, DIFFERENCES WITH ALLIGATORS factsanddetails.com

PREHISTORIC CROCODILES: EVOLUTION, EARLIEST SPECIES, TRAITS factsanddetails.com

CROCODILE BEHAVIOR: COMMUNICATION, FEEDING, MATING factsanddetails.com

SPECIES OF CROCODILES IN ASIA factsanddetails.com

CROCODILES AND HUMANS: WORSHIP, THREATS, HANDBAGS factsanddetails.com

CROCODILE ATTACKS IN ASIA factsanddetails.com

GHARIALS: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR, REPRODUCTION, CONSERVATION factsanddetails.com

False Gharial Habitat and Where They Are Found

False gharials are freshwater crocodiles native to Peninsular Malaysia, Sumatra, western Java and Borneo. There were once found in India but have disappeared from there. There have been unconfirmed reports of false gharials in Vietnam and Sulawesi. [Source: Katie Foster, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

False gharial populations are isolated and occur in low densities throughout their range. The largest known populations are in Sumatra and Kalimantan, with smaller established populations in Malaysia. The highest density population of false gharials is in Tanjung Puting National Park in Kalimantan. On Borneo there are also found in western Sarawak and Brunei.

In the 1990s, information and sightings were available from 39 localities in 10 different river drainages, along with the remote river systems of Borneo. Apart from rivers, they inhabit swamps and lakes. Prior to the 1950s, False gharials occurred in freshwater ecosystems along the entire length of Sumatra east of the Barisan Mountains. The current distribution in eastern Sumatra has been reduced by 30-40 percent due to hunting, logging, fires and agriculture.

False gharials live in a variety of tropical habitats; lowland freshwater swamp forests, lakes, ponds, rivers and streams, temporary pools, marshes, swamps, bogs, areas adjacent to rivers and other water bodies, flooded forests, peat swamps, blackwater streams and rivers, and the fringes of rainforests near slow-moving rivers. They prefer peat swamp areas with low elevation and acidic, slow-moving muddy water; and also like secondary forest habitat, characterized by more defined river channels and banks, higher pH and elevation, and lack of peat mounds. False gharials need terrestrial areas for basking and nesting. They are rarely found at elevations above 20 meters (65.62 feet). In the water they are typically found at depths of 0.30 to 1.10 meters (0.98 to 3.61 feet). /=\

False Gharial Characteristics

False gharial are a bit smaller than gharials. They range in weight from 93 to 210 kilograms (205 to 463 pounds) and range in length from four to five meters (13 to 16.4 feet). Sexual Dimorphism (differences between males and females) is present: Males are longer and heavier than females. Three mature males kept in captivity measured 3.6 to 3.9 meters (12 to 13 feet) and weighed 190 to 210 kilograms (420 to 460 pounds), while a female measured 3.27 meters (10.7 feet) and weighed 93 kilograms (210 pounds). There have been reports of males reaching a size of five meters.[Source: Katie Foster, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

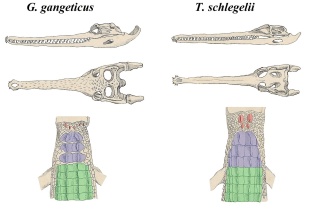

The most notable feature of false gharials is their extremely long and slender snout, which is slimmer than the snout of slender-snouted crocodilea and comparable to the snout of ghariala. False gharials have 76 to 84 sharp pointed teeth, similar to those gharials, which both species use to catch fish. False gharials get their common name form the similarity of their snout and teeth to those of gharials.

False gharials are cold blooded (ectothermic, use heat from the environment and adapt their behavior to regulate body temperature). They have a streamlined body and muscular tail and a palatal valve that prevents water from entering the throat while underwater. Their eyes and nostrils are on top of the head, which allows them to breath and see above the water while their bodies are submerged under the water, Both adults and juveniles have dark, sometimes reddish or chocolate brown coloration, with black banding on the tail and body and dark patches on the jaws. Their undersides are cream-colored or white.

Gharials (Gavialis gangeticus) and false gharials look similar, The most obvious difference between the two species is color: False gharials are red-brown with dark spots; gharials are green-gray and darken with age. They also live in different places. False gharials live in Malaysia and Indonesia; gharials live in Bangladesh, Nepal and India. [Source: Sascha Bos, HowStuffWorks, January 18, 2024]

False Gharial Food and Eating Behavior

False gharial are primarily carnivores (eat meat or animal parts) but are also recognized as piscivores (eat fish). Animal foods eaten by adult and juveniles include fish, birds, mammals, reptiles, insects, non-insect arthropods and aquatic crustaceans. [Source: Katie Foster, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

Until recently it was thought the diet of false gharials was similar to that of true gharial — namely that they ate only fish and very small vertebrates, but new evidence, observation and studies indicate false gharial's broader snout (broader than the snouts of gharials) allows them to prey on larger vertebrates such as Proboscis monkeys, long-tailed macaques, deer and flying foxes. In 2008, a female measuring more than four meters long swallowed a fisherman in central Kalimantan. His remains were found in the gharial's stomach.

False gharials are opportunistic carnivores. They have been reported to grab crab-eating macaques (a kind of monkey) and other macaques from river banks, submerging and drowning their prey or beating it against the bank. Other prey items include wild pigs, mouse deer, dogs, otters, fish, birds, turtles, snakes, monitor lizards, and aquatic and terrestrial invertebrates.

False Gharial Behavior

False gharials are terricolous (live on the ground), natatorial (equipped for swimming), diurnal (active during the daytime), nocturnal (active at night), crepuscular (active at dawn and dusk), motile (move around as opposed to being stationary), sedentary (remain in the same area) and solitary. They sense and communicate with vision, touch, sound, vibrations and chemicals usually detected with smell. Home range size and territorial behaviors have not been observed in the wild. In captivity, several males and females can be housed in a single enclosure without any conflicts.[Source: Katie Foster, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

False gharials spend most of their time submerged in shallow wallows or mud-holes, with only their eyes and nostrils visible. They have been observed basking but not often as often as other species. Basking behavior is usually used as an aid in thermoregulation (the homeostatic process of maintaining a steady internal body temperature despite changes in external conditions) It has been suggested that false gharials may occasionally occupy burrows, maybe to aid thermoregulation . /=\

Communication among false gharials has not been observed much in the wild. During the breeding seasom it is assumed that they communicate visually and through touch and smell. Most crocodilians use a variety of calls to communicate with members of their own species and to other animals, but such communication not been documented with false gharials. Surprisingly, their mating appears to be mostly silent, without being accompanied by calls.

False Gharial Mating, Reproduction and Offspring

False gharials are oviparous, meaning that young are hatched from eggs, and mound-nesters. It is believed they engage in seasonal breeding but it is is not known when they breed in the wild or when the nesting season is. In captivity they may breed twice yearly, usually during the wet seasons: November-February and April-June. The number of eggs laid ranges from 20 to 60, with a typical clutch comprising of 13 to 35 eggs in one nest. The incubation period ranges from 90 to 115 days. After that young hatch and are left to fend for themselves. Minimal parental care is provided by females. Males exhibit no parental involveemnt other than fertilization. On average females and males reach sexual or reproductive maturity at 20 years. Sexual maturity in females appears to be attained at around 2.5 to 3 meter (8.2 to 9.8 feet), which is large compared to other crocodilians.[Source: Katie Foster, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

False gharials produce the largest eggs of all crocodilians. They have a soft inner membrane and harder, calcified shell, weigh up to 155 grams each and are up to 9.5 centimeters long and 6.2 centimeters wide, with a total mass roughly double that of any other species. . Crocodilian sex is determined by temperature. Once the building of the nest mound is completed and eggs are laid the female abandons her nest, leaving the young alone and at risk of being eaten by predators like mongooses, tigers. leopards, civets, and wild dogs. Young resemble small adults upon hatching. They are equipped with an “egg tooth” — a pointed structure on the end of the snout — that allows them to slice through the egg shell. After a few weeks later the egg tooth recedes.

According to Animal Diversity Web: Very little is known about the natural mating behaviors of false gharials; most details are from captive breeding programs, with a few acocunts from the wild. Courtship behavior and nesting appear to take place during the rainy season in both cases. Males approach females in the water, swimming around them. In some cases, this is accompanied by both animals hitting each other with their tails, in others copulation proceeds immediately. The male mounts the female, wrapping his tail around and under hers. Copulation occurrs once a day for several days to a week, and is accompanied by a strong odor. One captive breeding program in Malaysia had success housing a group of three males and one female. The female chose the largest male and appeared to stay near him during the courting period. When two females were kept in the same enclosure with the males, no mating occurred and it is theorized that females living in close proximity may suppress breeding in one another. /=\

Nesting Mounds are usually constructed on land at the shady base of a tree near water, using sand and vegetation including peat, twigs, tree seeds, and dried leaves. Females have been observed beginning nest building a month or more after copulation and laying a clutch of 20-60 eggs 1-2 weeks after beginning to nest. After eggs are laid, more vegetation is added to the top of the nest by the female. Mounds typically measure 45-60 centimeters high and 90-110 centimeters in diameter. Eggs are laid just above ground level and the temperature within the nest fluctuates depending on the environment and rainfall (records in captivity of 26°C-32°C). Captive breeding initiatives have shown that abundant vegetation improves the chances of breeding because it provides more cover and nesting material for the female. Females have occasionally been observed sitting on top of nest mounds or defending them by stomping the ground, but more often flee the nest if approached. There is evidence that females may help to excavate nests before or during hatching. but they have not been observed helping hatchlings to the water as some crocodilians do. No parental investment: beyond this has been observed. /=\

False Gharials, Humans and Conservation

On the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List false gharials are listed as Endangered; US Federal List: Endangered No special status. In CITES (Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild) they are in Appendix I, which lists species that are the most endangered among CITES-listed animals and plants. [Source: Katie Foster, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

False gharials are threatened throughout most of their range mainly due to the drainage of their freshwater swamplands and clearance of surrounding rainforests. They have also been hunted for their skins and meat, and their eggs have been harvested for human consumption and use in traditional medicine.

Sightings and captures of wild false gharials specimens have been rare. Simply located them is difficult. Populations tend to be very small and restricted to small patches of swamp or forest. There has been a significant decline in the density of populations since the 1940s. In 2000, the Crocodile Specialist Group estimated that there were less than 2,500 adults remaining in the wild.

The Crocodile Specialist Group False gharials Task Force (CSG-TTF) has carried out field research, implemented programs to raise international awareness, and produced reports on conservation priorities and captive breeding. Threats to False gharials other than those names above include habitat loss through forest fires, logging, agriculture development, slash and burn agriculture, and dam building. These activities have reduced this species' range in Sumatra by 30 to 40 percent. False gharials are legally protected throughout their entire range, but enforcement of laws designed to protect them are insufficient to maintain stable populations and breeding habitat. Trade of the species is also prohibited by law, but not well enforced.

False Gharial Attacks on Humans

In 2008, a four-meter female false gharial attacked and ate a fisherman in central Kalimantan. His remains were found in the gharial's stomach. This was the first verified fatal human attack by a false gharial. However, by 2012, at least two more verified fatal attacks on humans by false gharials had occurred, possibly indicating an increase of human-false gharial conflict possibly brought on by a decline of habitat, habitat quality, and natural prey numbers. [Source: Wikipedia]

The Orangutan Foundation reported: On December 31, 2008,a local man was killed and eaten by a large crocodile. A group of people went out the same night to look for the man and the crocodile but found neither. The next day they called on a pawang or shaman who has the ability to call crocodiles. He worked his magic and within 17 hours of the attack the crocodile was caught and killed; it was almost five meters long and must have been over 50 years old. Inside were the remains of the man. [Orangutan Foundation, January 23, 2009]

What makes this interesting, as well as tragic, is the crocodile was a Malaysian false gharial. In 2008, Rene Bonke was out here studying them. They are one of the crocodile species never reported to have attacked people... Devis, Pondok Ambung Manager, has been leading the investigation and yesterday we went out to look at the site where the attack occurred.

It isn't surprising Tomistoma kill people. What surprised me was the river where the attack happened. It was an ordinary, peaceful, black-water creek, not 15 minutes upstream from town. It was identical to literally dozens of such rivers that I have seen, been up, even waded across. Never once did it occur to me that such a large Tomistoma might live there. They are an endangered species and you rarely see them. Being in that place, where I knew someone had died, gave me pause. But behind that was a wonder; a wonder that in this era of chainsaws, speedboats and wanton habitat destruction, an animal of such size could have survived for so long.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Animal Diversity Web animaldiversity.org ; National Geographic, Live Science, Natural History magazine, David Attenborough books, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Discover magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Wikipedia, The Guardian, Top Secret Animal Attack Files website and various books and other publications.

Last updated February 2025