CROCODILE HISTORY

Crocodiles have been around for 240 million years, appearing 25 million years before the first dinosaurs and 100 million years before the first birds and mammals. Crocodiles that lived 230 millions years ago were up to 40 feet long. "Our primate ancestors were ratty little things that went around stealing eggs," Dr. Perran Ross, a crocodile specialist and professor of wildlife ecology and conservation at the University of Florida, told the New York Times. "Ancestral crocodiles had basically the same body plan we see today, apparently because it works."

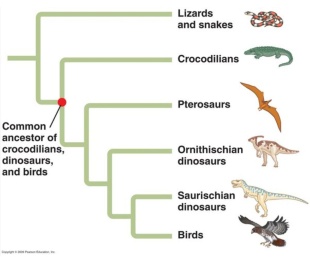

Crocodilians (alligators, crocodiles, and gharials) and birds are regarded as the closest living relatives of dinosaurs. They have many dinosaur-like features including bird-like arrangements of the hip bones, and teeth that are mounted in sockets rather than being fused directly to the jawbone. Recent taxonomic analysis has reasoned that dinosaurs, crocodiles and birds should be classified in same the branch of animals.

Crocodiles are more closely related to birds than they are to snakes, geckos and other reptiles. Birds and crocodiles, for example, have sophisticated four chambered hearts, while lizards and snakes have only three chambers. A four-chamber heart boosts brain performance and offers more flexibility to changing environments than a three-chamber heart. Crocodiles display a number of bird-like behaviors such as building good nests, and brooding, protecting and fussing over their eggs.

RELATED ARTICLES:

CROCODILES: CHARACTERISTICS, ANATOMY, DIFFERENCES WITH ALLIGATORS factsanddetails.com

CROCODILE BEHAVIOR: COMMUNICATION, FEEDING, MATING factsanddetails.com

SPECIES OF CROCODILES IN ASIA factsanddetails.com

SALTWATER CROCODILES factsanddetails.com

CROCODILES AND HUMANS: WORSHIP, THREATS, HANDBAGS factsanddetails.com

HOW TO CATCH A CROCODILE factsanddetails.com

CROCODILE ATTACKS IN ASIA factsanddetails.com

CROCODILES IN AUSTRALIA: HISTORY, SPECIES, BIG ONES, DWARVES, BATS, SHARKS ioa.factsanddetails.com

CROCODILE CULTURE AUSTRALIA: URBAN CROCS, ABORIGINALS, DUNDEE, STEVE IRWIN ioa.factsanddetails.com

CROCODILE ATTACKS IN AUSTRALIA: HOW, WHERE, WHY, DETAILS ioa.factsanddetails.com

CROCODILE ATTACKS IN NORTHERN TERRITORY AUSTRALIA ioa.factsanddetails.com

SURVIVING CROCODILE ATTACKS IN AUSTRALIA ioa.factsanddetails.com

Archosauria

Crocodilians belong to a sister group with birds and dinosaurs called Archosauria ("ruling reptiles"). Crocodilians and birds are the only survivors of the once-prevalent Archosauria clade — a group of diapsid sauropsid tetrapods (roughly meaning four-limbed dinosaur-era reptiles with two holes in their skull) that also included non-avian dinosaurs, pterosaurs (flying dinosaurs), phytosaurs (semiaquatic Late Triassic reptiles), aetosaurs (armored dinosaurs) and rauisuchians (mostly large, carnivorous Triassic-ere dinosaurs) as well as many Mesozoic marine reptiles. Modern paleontologists define Archosauria as a crown group that includes the most recent common ancestor of living birds and crocodilians, and all of its descendants. Although broadly classified as reptiles, which traditionally exclude birds, the cladistic sense of the term includes all living and extinct relatives of birds and crocodilians. [Source: Wikipedia]

During the Mesozoic Period (245-65 million years ago) — Archosauria, including dinosaurs and other reptiles, dominated life on all continents and in the oceans. Most or all of crocodilians' adaptations had already evolved by the late Triassic (about 200 million years ago). Crocodilians are the most advanced surviving reptiles; many of their features are more similar to mammals or birds than to other reptiles.[Source: Danny Goodisman, Animal Diversity Web (ADW), September 9, 2002]

Archosaurs divided into two groups during the Triassic Period (252 to 201 million years ago), which was part of the Mesozoic era. Both of these groups have surviving representatives: the descendants of dinosaurs (birds) and crocodilians. The crocodilians are the descendants of pseudosuchian archosaurs. Modern crocodiles are similar enough to be mistaken for one another by most people, but their ancient ancestors had a variety of sizes and lifestyles. Fossil evidence suggests that pseudosuchians reached great diversity quickly following the devastating End-Permian mass extinction. [Source: Laura Baisas, Popular Science, July 11, 2024]

According to Popular Science: “A growing number of recent discoveries of Middle Triassic pseudosuchians are hinting that an underappreciated amount of morphological and ecological diversity and experimentation was happening early in the group’s history. While a lot of the public’s fascination with the Triassic focuses on the origin of dinosaurs, it’s really the pseudosuchians that were doing interesting things at the beginning of the Mesozoic,” Nate Smith, a study co-author and Director and Curator of the Dinosaur Institute at the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County (NHMLAC) said.

Evolution of Crocodiles

Mel White wrote in National Geographic, “Today's crocodilians are often said to be survivors from the age of dinosaurs. That's true as far as it goes: Modern crocs have been around for some 80 million years. But they're only a small sampling of the crocodilian relatives that once roamed the planet — and, in fact, once ruled it. Crurotarsans (a term paleontologists use to include all croc relatives) appeared about 240 million years ago, generally at the same time as dinosaurs. During the Triassic period, crocodile ancestors radiated into a wide array of terrestrial forms, from slender, long-legged animals something like wolves to huge, fearsome predators at the top of the food chain. Some, like the animal called Effigia, walked at least part of the time on two legs and were probably herbivores. So dominant were crurotarsans on land that dinosaurs were limited in the ecological niches they could occupy, staying mostly small in size and uncommon in number. [Source: Mel White, National Geographic , November 2009]

At the end of the Triassic, about 200 million years ago, an unknown cataclysm wiped out most crurotarsans. With the land cleared of their competitors, dinosaurs took over. At the same time, huge swimming predators such as plesiosaurs had evolved in the ocean, leaving little room for interlopers. The crocs that survived took on a new diversity of forms, but eventually they lived, as their descendants do today, in the only places they could: rivers, swamps, and marshes.

Restricted ecological niches may have limited the creatures' evolutionary opportunities — but also may have saved them. Many croc species survived the massive K-T (Cretaceous-Tertiary) extinction 65 million years ago, when an asteroid dealt a death blow to the dinosaurs (except for birds, now viewed as latter-day dinosaurs) and a broad range of other life on land and in the oceans. No one knows why crocs lived when so much died, but their freshwater habitat is one explanation: Freshwater species generally did better during the K-T event than did marine animals, which lost extensive shallow habitat as sea level dropped. Their wide-ranging diet and cold-blooded ability to go long periods without food may have helped as well. With land-based dinosaurs and sea monsters gone, why didn't crocs take over the Earth once and for all? By then mammals had begun their evolutionary march toward world domination. Over time the most divergent lines of crocs died out, leaving the squat-bodied, short-legged forms we're familiar with.

All modern crocodilians have adapted to a semi-aquatic life, although as recently as 3000 years ago there may have been a terrestrial crocodilian species on New Caledonia. Some crocodiles may venture into larger bodies of fresh or salt water, but all must lay their eggs on dry land. Most crocodilians live in the tropics. The only exceptions are the American alligator (Alligator mississippiensis) and the Chinese alligator (Alligator sinensis), and they still cannot tolerate climates colder than temperate climates. No crocodilians venture out of lowlands; it is speculated that none ever lived above 1000 meters (3260 feet) above sea level. [Source: Danny Goodisman, Animal Diversity Web (ADW), September 9, 2002]

Pseudosuchia to Crocodiles

Archosaurs belong to a group called Pseudosuchia, which includes numerous species that are more closely related to crocodiles than they are to birds. Pseudosuchias went extinct around the time of the Triassic–Jurassic extinction event about 201.4 million years ago. One group — the crocodylomorphs — survived this extinction and gave rise to the crocodiles. [Source: Laura Baisas, Popular Science, December 4, 2023]

In a study published December 4, 2023 in the journal Nature Ecology & Evolution, a team of scientists announced that they had mapped the crocodile family tree, including extinct called Pseudosuchia. Laura Baisas wrote in Popular Science: In the study, a team of researchers used the fossil record to build a large phylogeny, or evolutionary family tree of a species or group. The phylogeny included crocodiles and their extinct relatives, so the team could map out how many new species were being formed and how many species were going extinct over time. They then combined this family tree with data on past changes in climate. They were particularly interested in changes to temperature and sea levels to see if the emergence and extinction of species could be linked to climate change.

They found that climate change and competition with other species have shaped the diversity of modern-day crocodiles and their extinct relatives. Surprisingly, the phylogeny also revealed that whether species lives in freshwater, in the sea, or on land plays a key role in its survival. When global temperatures increased, the number of species of the modern crocodile’s sea-dwelling and land-based relatives also went up.

The crocodile’s freshwater relatives were not affected by changes in temperatures. Rising sea levels proved to be their greatest risk for extinction. According to the team, these results provide important insights for conservation efforts of crocodiles and other species in the face of human-made climate change. Study co-author and University of York biologist Katie Davis said: “With a million plant and animal species perilously close to extinction, understanding the key factors behind why species disappear has never been more important,” said Davis. “In the case of crocodiles, many species reside in low-lying areas, meaning that rising sea levels associated with global warming may irreversibly alter the habitats on which they depend.”

237-Million-Year-Old Crocodile-Like Reptile

In a study published in Scientific Reports in June 2024, paleontologists announced that they had discovered fossils of new crocodile-like reptile species that lived 237 million years ago. The fossils, found in a fossiliferous locality named "Linha Várzea 2" in southern Brazil, were dubbed Parvosuchus aurelioi. The new species belongs to a group of crocodile-like reptiles called pseudosuchians and are the first "unequivocal" gracilisuchid, an extinct genus of tiny pseudosuchians, Rodrigo Müller, a paleontologist at the Universidade Federal de Santa Maria and lead author of the paper, told ABC News. [Source: Julia Jacobo, ABC News, June 21, 2024]

ABC News reported: Before dinosaurs dominated the earth, pseudosuchians were a common form of reptile during the Triassic Period. The fossils were discovered in fossiliferous beds that precede the ones housing the oldest dinosaurs, giving scientists clues on the "ecosystems that existed before the dawn of the dinosaur era," Müller said. "The presence of this small predator among fossils of much larger predators suggests that these ecosystems, where Brazil is located today, were more complex than previously imagined," he said.Gracilisuchids are extremely rare, Müller said, adding that there are only other three species worldwide: two from China and one from Argentina. The smaller pseudosuchians lived alongside the larger apex predators, according to the paper.

The Parvosuchus aurelioi fossils consist of a partial skeleton, including a complete skull, which includes the lower jaw, 11 dorsal vertebrae, a pelvis and partially preserved limbs. The skull measures at less than six inches in length and features long slender jaws with pointed teeth that curved backwards, as well as several skull openings. Müller estimates the animal was about 6.5 feet long and had a long tail. It likely stood on four legs that were adapted to walk on land and had blade-like teeth that could tear flesh.

Benggwigwishingasuchus Eremicarminis

In a study published on July 10, 2024 in the journal Biology Letters, scientists announced the discovery of new species of pseudosuchian archosaurs named Benggwigwishingasuchus eremicarminis (“Fisherman Croc’s Desert Song,”) in the Triassic Era Favret Formation of Nevada that during the Middle Triassic Period (247.2 and 237 million years ago), a time when ichthyosaurs ruled the oceans and the ancestors of crocodiles ruled the shores.

“Our first reaction was: What the hell is this?” study co-author and University of Bonn paleontologist Nicole Klein said in a statement. “We were expecting to find things like marine reptiles. We couldn’t understand how a terrestrial animal could end up so far out in the sea among the ichthyosaurs and ammonites. It wasn’t until seeing the nearly completely prepared specimen in person that I was convinced it really was a terrestrial animal.” [Source: Laura Baisas, Popular Science, July 11, 2024]

Laura Baisas wrote in Popular Science: Pseudosuchian archosaurs have been discovered on what used to be the shores of the ancient Tethys Ocean in what is now Europe. B. eremicarminis is the first coastal representative from the Panthalassan Ocean and western hemisphere. This means that these crocodile relatives lived in coastal environments worldwide during the Middle Triassic. These coastal species do not all belong in the same evolutionary group. Pseudosuchians–and archosauriforms more broadly–were potentially adapting to life along various shores independent of one another. Essentially, it looks like you had a bunch of very different archosauriform groups deciding to dip their toes in the water during the Middle Triassic. What’s interesting, is that it doesn’t look like many of these ‘independent experiments’ led to broader radiations of semi-aquatic groups,” said Smith.

B. eremicarminis likely would have been about five to six feet long, but the team does not know exactly how large it was. They found a few elements of the individual’s skull, but any clues to how it fed and hunted are also absent. However, what is more clear is that B. eremicarminis likely stayed fairly close to the shore. Its limbs were well-preserved over time and well-developed without any of the signs of aquatic living, including flippers or altered bone density.

Were the Earliest Crocodilian Ancestors Warm Blooded and Land-Based?

In a study published in Paleobiology in June 2019, Jorge Cubo of Sorbonne University in Paris announced that his examination of a 237-million-year-old reptile indicated that earliest ancestors of the crocodile family were warm-blooded (endothermic:) This finding built on researchers by Roger Seymour, an evolutionary biologist at the University of Adelaide in Australia, and Christina Bennett-Stamper, a research microscopist at the federal Environmental Protection Agency, who co-authored a landmark 2004 paper arguing that the ancestral crocodyliforms weren’t just steppingstones to warmblooded archosaurs, like dinosaurs and birds: they were warmblooded themselves. Bennett-Stamper had described a process by which alligator embryos develop a unique opening just before hatching that allows blood to bypass the lung. The process turns “an endothermic heart into an ectothermic one”. Dr. Seymour said. Modern crocodilians ectothermic (cold blooded). [Source:Asher Elbein, New York Times, June 3, 2019]

Asher Elbein wrote in the New York Times: In 2016, Dr. Cubo decided to try and nail down a date. He went foraging in the collections of the French National Museum of Natural History for the oldest archosaur relative he could find. He settled on Azendohsaurus, a squat Triassic herbivore whose skull had once been misidentified as belonging to an early dinosaur. “In order to get a sense of Azendohsaurus’s metabolism, Dr. Cubo and his colleague Nour-Eddine Jalil took slices of bone and examined the microscopic structure. The researchers also examined 14 related archosaurs, plus tissue and metabolic data from living species, including amphibians, lizards, turtles, crocodiles, mammals and birds.

“To their surprise, the investigators found that Azendohsaurus likely had a resting metabolism significantly higher than most living ectotherms, and similar to living mammals and birds. That suggested that archosaur relatives of the Late Triassic Period already were warmblooded, potentially pushing the origins of endothermy in the family all the way back to the Permian Period, more than 260 million years ago. “Early crocodyliforms were probably terrestrial and warmblooded,” Dr. Cubo said.

“Christopher Brochu, a paleontologist at the University of Iowa, is cautious. It’s true that fossils suggest the animals were “faster on their feet than their living relatives, which implies a somewhat higher metabolic rate and possibly a position on the spectrum farther from the coldblooded end than modern crocodilians,” he said. But that may not mean they were warmblooded, Dr. Brochu added. The warmer climate of the Late Triassic Period and Early Jurassic Period may have helped boost the metabolism of early crocodile relatives without requiring a fully endothermic metabolism. Lizards living in hot climates, for example, can easily outpace most of their mammalian predators, as anyone who’s ever chased one can testify. “Coldblooded and warmblooded aren’t fixed categories — they’re end members of a spectrum,” Dr. Brochu said. “Some animals fall closer to one end, and others fall closer to the opposite.”

“During the Mesozoic Era, multiple lineages of crocodilians returned to the water. Among them were juggernauts like the dinosaur-killing Deinosuchus, as well as the ancestors of modern crocodiles. This transition from active land animals to semiaquatic ambush predators is likely why modern crocodiles evolved a more coldblooded lifestyle, according to Dr. Seymour. “The advantages are enormous,” he said. With a slow metabolism, crocodiles can fast for months, can hold their breaths up to ten times longer, and don’t have to expend energy staying warm against the tremendous cooling power of water. A slower metabolism helps alligators hibernate in the winter and saltwater crocodiles ride ocean currents for hundreds of miles. “Such a metabolism “is quite a good adaptation if in a high-stress environment or situation in which maybe being underwater would provide more safety,” said Marisa Tellez, a crocodile parasitologist at the University of California, Santa Barbara.

Dinosaur-Like Crocodiles

Some ancient ancestors of crocodiles looks more like dinosaurs than crocodiles. In 2006 Carl Zimmer wrote in the New York Times, Scientists at the American Museum of Natural History have discovered a fossil in New Mexico that looks like a six-foot-long, two-legged dinosaur similar to a tyrannosaur or a velociraptor. But it is actually an ancient relative of modern alligators and crocodiles. Carl Zimmer wrote in the New York Times, January 26, 2006]

The reptile stood on its hind legs, keeping its tail erect. Its arms were tiny, its neck long, its eyes huge. It was toothless, and its jaws were covered in hard tissue, like a bird's beak. Although the 210-million-year-old fossil was more closely related to alligators and crocodiles, it bore an uncanny resemblance to a group of dinosaurs that evolved 80 million years later, known as ornithomimids, or ostrich-mimics. The similarity extends to subtle details, like air sacs in the vertebrae of both animals. Nesbitt and Norell named the fossil Effigia okeeffeae. Effigia means "ghost," referring to the decades that the fossil remained invisible to scientists. The species name honors the artist Georgia O'Keeffe, who lived not far from the fossil site. A paper describing their results will be published in The Proceedings of the Royal Society.

Effigia is a striking example of what biologists call convergence, when two lineages evolve the same body plan. Other examples of convergence include marsupials related to kangaroos and opossums that evolved into creatures resembling lions and wolves."When I first saw the skull, I thought this can't be related to crocs," said Christopher Brochu, an expert on crocodilian evolution at the University of Iowa. "But then I saw the ankle and said, 'Yep, it's a croc.' So ornithomimids were convergent on Effigia 80 million years later. There are only so many ways you can do something, and as a result you get this convergence."

Paul Sereno, a paleontologist from the University of Chicago, and his research team have uncovered fossils of a number of crocodile ancestors in the Sahara in Niger and Morocco that populated Gondwana — today's southern continents — approximately 110 million years ago. Described in a November 2009 National Geographic article, they include: 1) The BoarCroc is a 20-foot long meat-eater with an armor snout it used to ram and three sets of fangs for slicing. Eye sockets turned forward enhanced stereoscopic vision to aid in hunting. Large, well-developed muscles gave the jaw extra biting power. 2) The RacCroc has a pair of buckteeth in the lower jaw to allow this croc to burrow in the ground for tubers. 3) The DogCroc has differentiated teeth and a soft nose pointing forward, and possibly escaped from predators with its lanky legs. 4) The DuckCroc has a broad overhanging snout and hook-shaped teeth which helped it to catch small fish or worms in shallow water.

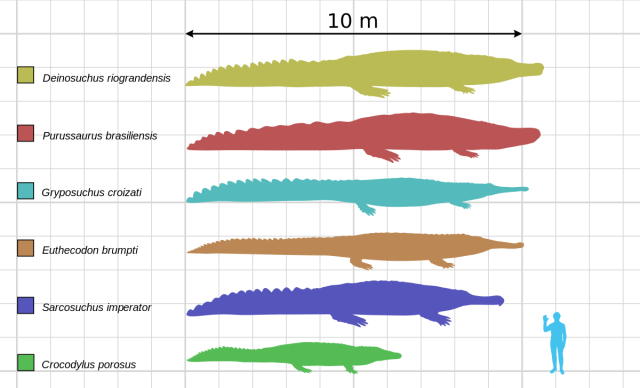

Sarcosuchus Imperator — 110-Million-Year-Old Super Croc

In 2000 in Gadoufaoua, a region of the Sahara in of Niger whose name means “where camels fear to go,” and one of Africa's richest sources of dinosaur fossils, Sereno found fossils of an awesome crocodile-like animal that scientists called Sarcosuchus imperator, a name that means "flesh crocodile emperor." Sereno's team nicknamed it "SuperCroc." The skull alone was six feet long! Sereno says it's "about the biggest I've ever seen." Based on the skull size and part of skeleton that was found and figuring the beast had the same basic configuration of modern crocodile, Sereno estimated that an adult SuperCroc could grow to be 40 feet long! That's roughly the length of a school bus. And the giant beast probably weighed as much as 10 tons. That's heavier than an African elephant. Those measurements make SuperCroc one of the largest crocodiles ever to walk the Earth. Today's biggest crocs grow to about 20 feet. [Source: Peter Winkler, National Geographic Classroom magazine, March 2002]

Peter Winkler wrote in National Geographic Classroom magazine: “Sereno believes SuperCroc lived about 110 million years ago when what is now the Sahara was covered by forests and was broken up rivers with masses of fish that SuperCroc fed on. Five or more crocodile species, or types, lurked in the rivers. SuperCroc, Sereno says, was "the monster of them all." What did SuperCroc eat. "Anything it wanted," Sereno says. SuperCroc's narrow jaws held about 130 teeth. The teeth were short but incredibly strong. SuperCroc's mouth was "designed for grabbing prey — fish, turtles, and dinosaurs that strayed too close." SuperCroc likely spent most of its life in the river. As is the cases with modern crocodiles water hid the creature's huge body. Only its eyes and nostrils poked above the surface.

“After spotting a meal, the giant hunter moved quietly toward the animal. Then — wham! That huge mouth locked onto its prey. SuperCroc dragged the stunned creature into the water. There the animal drowned. Then it became food. Dinosaurs surely fought back when SuperCroc grabbed them. But we don't know of any creatures that went after this huge reptile. Just in case, though, SuperCroc wore serious armor. Huge plates of bone, called scutes (skoots), covered the animal's back. Hundreds of them lay just below the skin. A single scute from the back could be a foot long!

“SuperCroc's long head is wider in front than in the middle. That shape is unique, or one of a kind. No other croc — living or extinct — has a snout quite like it. At the front of SuperCroc's head is a big hole. That's where the nose would be. That empty space may have given the ancient predator a keen sense of smell. Or perhaps it helped SuperCroc make noise to communicate with other members of its species.

“The giant beast probably lived only a few million years. That raises a huge question: Why didn't SuperCroc survive? Sereno suspects that SuperCrocs were fairly rare. After all, a monster that big needs plenty of room to make a living. Disease or disaster could have wiped out the species pretty quickly. But no one knows for sure what killed SuperCroc. That's a mystery for future scientists — maybe even you.

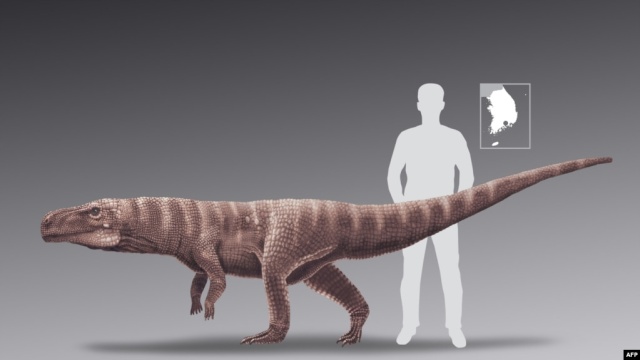

Crocodylomorph Walked on Two Legs Over 105 Million Years Ago

A study, published in the journal Scientific Reports in June 2020, describes ancient fossilized footprints discovered in South Korea originally been thought to belong to a pterosaur — a flying dinosaur — that had been walking on two legs — actually belonged to a bipedal crocodile that was semi-adapted to land. [Source: VOA News, June 12, 2020]

This is the first evidence from this time period of a bipedal crocodylomorph, a branching, diverse group of animals that includes crocodilians and their extinct relatives. The researchers named the new species Batrachopus grandis. The footprints were 18 to 24 centimeters long, suggesting that the creatures’ bodies were almost 3 meters long. They seem to have been left only by the back limbs, showing a clear heel-to-toe walking pattern.

Scientists identified Batrachopus grandis as a crocodile relative based on fossilized footprints. The tracks showed detailed impressions of toes, foot pads, and even skin patches, which closely resembled the foot structure of a crocodile. The narrow trackway with only hind foot impressions indicated the creature walked on two legs. The presence of distinct heel impressions in the footprints further supported the idea of a more upright posture.

The well-preserved fossils, discovered in South Korea's Jinju Formation, date to the lower Cretaceous period, which spanned 145 million to 105 million years ago. A 2015 study describes at least one instance of a bipedal crocodylomorph believed to have lived in the southeastern U.S. state of North Carolina 230 million years ago.

95-Million-Year-Old Crocodile Had a Dinosaur as its Last Meal

In a study published in February 2022 in the journal Gondwana Research, scientists announced that a species of crocodile that lived about 95 million in Australia ate a dinosaur as its final meal. Jordan Mendoza wrote in USA TODAY: “The fossils of the crocodilian species were first found in 2010 near the Winton Formation in eastern Australia, a rock bed from the Cretaceous period, when most of the commonly known dinosaurs were roaming Earth.“Some of the fossils of the crocodile were partially crushed, but researchers noticed that within the fossils were numerous small bones that belonged to another animal. Researchers at the Australian Age of Dinosaurs Museum have identified those smaller bones as belonging to a dinosaur. [Source: Jordan Mendoza, USA TODAY, February 17, 2022]

“The freshwater crocodile, named Confractosuchus sauroktonos, which means "the broken dinosaur killer," was over eight feet long. But Matt White, research associate at the museum and lead researcher, said it would have grown much larger. Researchers were unsure how the crocodile died. About 35 percent of the animal was preserved; it was missing its tail and limbs but had a near-complete skull. Researchers then used X-ray and CT scans to find out what bones were inside the remains.

“The findings showed the remains belonged to a 4-pound juvenile ornithopod, a group of plant-eating dinosaurs that included duck-billed creatures. The ornithopod's remains also were the first of their kind found in Australia, suggesting it is a newly discovered species. What was left inside the crocodile's stomach was one of the ornithopod's femurs "sheared in half" and the other with a bite mark so hard a tooth mark was left. That led researchers to believe the Confractosuchus "either directly killed the animal or scavenged it quickly after its death."

Crocodiles Lived Spain Until 4.5 million Years Ago

In October 2023, paleontologists in Spain announced that they had unearthed a 4.5 million-year-old tooth that likely belonged to one of the last crocodiles in Europe. The tooth was the only crocodilian fossil excavated from a site called Baza-1 in the southern province of Granada. The tooth indicates the reptile looked similar to Nile crocodiles that live in Africa today. Baza-1 was first excavated in the early 2000s and has yielded more than 2,000 fossils, despite only covering an area of 30 square meters (323 square feet). [Source: Sascha Pare, Live Science, October 19, 2023]

"The tooth we found at the site of Baza-1 corresponds to a true crocodile," said Bienvenido Martínez Navarro, a paleontologist with the Catalan Institution for Research and Advanced Studies (ICREA) and research professor at the Catalan Institute of Human Paleoecology and Social Evolution (IPHES) who co-led the recent excavations. "We have classified it as Crocodylus because, at the moment, the only evidence of its presence at this site is this tooth, and we don't have enough anatomical resolution to be more precise," Martínez Navarro told Live Science. This is the most recent evidence of a crocodile ever found in the fossil record in Europe, Martínez Navarro said. Until now, fossils suggesting crocodiles roamed the continent came from earlier deposits, including from the Miocene (23 million to 5.3 million years ago) and from very early on during the Pliocene (5.3 million to 2.6 million years ago).

According Live Science: Crocodiles likely crossed over from Africa to Europe around 6.2 million years ago, just before the Mediterranean Sea dried up during what is known as the Messinian salinity crisis, Martínez Navarro said. The Messinian salinity crisis was partly triggered by a global cooling event that locked ocean water up in glaciers and icebergs, lowering sea levels by about 230 feet (70 meters), according to the University of Maryland. This drop resulted in less water flowing from the Atlantic Ocean into the Mediterranean. Meanwhile, tectonic shifts also caused the ocean floor around the Strait of Gibraltar to rise, isolating the Mediterranean, which ultimately became disconnected from the world's oceans and dried up. This left behind a vast expanse of salt up to 2 miles (3 kilometers) thick in some places, which scientists found buried beneath hundreds of feet of sediment in the 1970s. "It was possible to walk from northern Africa to the Iberian Peninsula," Martínez Navarro said, adding that several species would have crossed this expanse. The Messinian salinity crisis lasted roughly 700,000 years and ended abruptly when a gigantic surge of water known as the Zanclean flood — triggered by evaporated water returning to the oceans and erosion of the strip of land around Gibraltar — replenished the Mediterranean Sea.

African crocodiles that found their way to modern-day Spain and Portugal likely disappeared when the climate became colder and drier during the Pliocene, Martínez Navarro said. The early Pliocene, however, was characterized by a tropical climate that supported a rich assemblage of animals — including now-extinct elephants, reptiles, amphibians and fish — whose remains were also unearthed at the site where the tooth was found.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Animal Diversity Web animaldiversity.org ; National Geographic, Live Science, Natural History magazine, David Attenborough books, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Discover magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, CNN, BBC, Wikipedia, The Guardian, Top Secret Animal Attack Files website and various books and other publications.

Last updated February 2025