NIAS ISLANDERS

The Nias live on the island of Nias and other islands near it off the west coast of Sumatra. Also known as the Niasan (English), Niasser (Dutch and German) and Ono Niha and Orang Nias (Indonesian), they have traditionally practiced slash-and-burn agriculture and as result many of the islands where they live are now deforested. They have traditionally farmed sweet potatoes, cassava and rice and fished with outrigger canoes. Cash crops include coffee, rubber, cloves, and patchouli oil. Pigs and gold are traditional indicators of wealth and are traditionally given as bride wealth and feasts of merit. [Source: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, East and Southeast Asia” edited by Paul Hockings (G.K. Hall & Company, 1993) ~]

According to the 2010 Indonesian census the Nias Islander population was 1,041,925. In 1985 the population was estimated to be over 531,000 (including 22,583 in the Batu Islands). The average density at that time was of 94.5 persons per square kilometer and the annual population growth was 2.6 percent. Nias people generally have a medium to tall build. Their average height ranges from 155 cm to 168 centimeters; Their faces tend to be oval with a fairly defined jawline, especially in men. Nias people's hair is usually black and tends to be thick. One of their most prominent characteristics of Nias Islanders is their eyes, which tend to be narrow, although not as narrow as those of Chinese people.

According to UNESCO: The people of Nias still maintain their traditional house, settlement patterns, and ornamental design. Ceremonies for the dead as well as thanksgiving festivals are conducted, but are not as complex as in Toraja. Upright stones are erected only occasionally within the housing compound. Most stages of life have traditionally been marked by ceremonies, usually accompanied by feasting. Ritual-regulated complex systems of exchange and measurement. Epidemics, believed to result from excessive profiteering, were addressed through expiatory sacrifices and the lowering of interest rates. In central regions, annual clan ceremonies (famongi) involving abstention from work were held after the harvest. For any major undertaking, household ancestor figures were decorated and offered sacrifices. Today, large-scale feasts of merit retain significance mainly in central Nias. [Source: Andrew W. Beatty, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5:East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993, UNESCO]

RELATED ARTICLES:

NIAS PEOPLE: HISTORY, LANGUAGE, RELIGION AND HEADHUNTING TRADITIONS factsanddetails.com

NIAS ISLAND: MEGALITHS, UNIQUE PEOPLE, SURFING factsanddetails.com

Nias Society and Kinship

Traditionally, Nias society has been hierarchical with the aristocratic upper caste at the top, followed by the common people, and below them slaves. Along with being warriors, the people of Nias are traditionally farmers, cultivating yams, maize and taro. Pigs were considered a mark of social status and the more pigs you had, the higher your status in the village. Nias society is centered around patrilineal clans (“mado”), whose name derives from an eponymous ancestor, with members of these clans often living in clusters of houses and sharing agriculture activities and economic responsibilities and recognizing the same guardian spirits. Marriage usually involves the payment of bride wealth not only to the bride’s family but also to her ancestors, sometimes up to 30 generations back.

Eric Kjellgren wrote: Culturally and artistically Nias island is divided into three discrete but related regions: North, Central, and South Nias. According to oral tradition all Nias islanders are descended from Hia, a single founding ancestor who descended to earth from Lowalangi (the upper world) and established humanity and society. Like many indigenous Southeast Asian peoples, the Ono Niha are separated into hereditary nobility who in some cases can trace their genealogy back to Hia, commoners, and, until the early twentieth century, slaves. [Source: Eric Kjellgren, “Oceania: Art of the Pacific Islands in The Metropolitan Museum of Art”, 2007]

Descent is patrilineal, and clans are widely dispersed. In central Nias, the local lineage constitutes the largest corporate descent group. Extending to a depth of roughly six generations, its members—who refer to themselves as sambua motua (“those of one ancestor”)—generally share land, cooperate in ritual, festive, and economic activities, venerate the same set of ancestral figures, and reside in the same or adjoining houses. Variations in marriage form do not affect patrilineal recruitment. The fostering of agnatic relatives or a sister’s child is common, whereas the adoption of non-kin is rare and was formerly associated with servitude. In southern Nias, patrilineal descent groups of varying scope are known as mo’ama. Precise information on descent organization in the northern and southern regions remains limited. Adherence to the ideal of clan exogamy varies considerably, both within and between regions.

Kinship terminology shows great regional variation and contextual complexity, defying simple classification. Across all regions, matrilateral cross-cousins are distinguished from other cousins and siblings. Relative age distinctions among siblings extend through successive generations, including grandchildren. Separate terms exist for wife givers and wife takers, though no prescriptive kinship equations apply.

The most prestigious clans are those claiming direct descent from the original ancestors, while other clans are regarded as offshoots. Prestige is primarily determined by seniority. Clans and families are further divided into social categories that include “nobles” (a conventional term indicating higher rank), “people” (sato or ono mbanua, literally “children of the village”), and, until the early twentieth century, “slaves.” The organization of these categories differs across the northern, central, and southern regions and is closely tied to political structures and to the ritual and festive practices that structure Niha social life. It is during these festivities that stone monuments are erected.

Nias Classes and Social Hierarchy

Nias in the south have two hereditary classes: nobles (si'ulu ) and commoners (sato ). Passage from one category to another is impossible. In the old days there were slaves (savuyu ) that were traded. They were mostly bonded laborers, captives or ransomed criminals. In the north and central areas the classes exist but not as rigidly and there was some mobility between the classes. Villages have typically been led by chiefs and noble village elders who have demonstrated their positions by hosting feasts of merit. Commoners can raise their status by hosting similar feasts. [Source: Andrew W. Beatty, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5:East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993; Viaro, Mario Alain, “Ceremonial Sabres of Nias Headhunters in Indonesia” , Arts et cultures. 2001, vol. 3, p. 150-171 =]

Ordinary villagers were called ono mbanua. Children born to a nobleman and a commoner woman in a secondary marriage were known as ono ba zato (“child by a commoner”), an intermediate and nonheritable status. Beyond these categories, social standing included further informal gradations that were continually renegotiated. Status was affirmed and elevated through feasts of merit, while influence was gained by accumulating credit within the system of festive payments. This system was carefully insulated from other forms of exchange—such as mutual aid or bride-wealth—through elaborate rules and distinct systems of measurement. In parts of northern Nias, however, bride-wealth and social rank were once integrated into a single graded scheme known as bosi (“steps”).

Social distinction rested primarily on genealogy. Members of the si’ulu elite sometimes traced their ancestry back dozens of generations. Wealth, mastery of customary law (adat), and formerly martial valor further reinforced claims to rank. Although the title si’ulu was hereditary, it required public confirmation through prescribed feasts. Ultimate authority belonged to the si’ulu who sponsored the greatest number of feasts in full accordance with customary law. In theory, the office of village chief (balö si’ulu or salawa) was contested each generation; in practice, succession usually remained within the same lineage. The chief’s eldest son, once he had completed the highest level of prescribed feasts, bore the title balugu.

Unlike the south, the central region lacked a clearly defined noble class. Any villager could, in principle, attain the highest social positions by demonstrating the capacity for advancement, particularly through the successful sponsorship of feasts and the erection of monuments—a pattern reflected in the abundance of megaliths in central villages. The central region was also a major center of headhunting and slave raiding, typically directed against southern villages or rival communities within the center.

The north and center differed in their social and territorial organization, both emphasizing the clan as a key marker of identity. In the north, the clan was closely linked to territorial and political organization through the öri, literally a “circle” of villages belonging to the same clan. Each öri was traditionally ruled by a clan patriarch (tuhen’öri), while individual villages were governed by their own chiefs without councils. Since about 1930, the öri has ceased to function in its original form. In the central region, social and political organization was based on both clan and lineage, and villages were traditionally led by a chief who was either the founder or a descendant of the founding ancestor.

Nias Governence and Social Organization

Traditionally Nias villages have been ruled by a chief who heads a council of elders (si'ila ) appointed from the commoner class. Most villages were originally founded by a single descent group, later becoming transformed into multiclan settlements. In the north and center there is an analogous hierarchy of ranks rather than classes, with greater social mobility and emphasis on achieved status. Hamlet or village chiefs are called salawa; satua mbanua, village elders, are men who have demonstrated superior qualities and mastery of custom by staging feasts of merit (ovasa). [Source: Andrew W. Beatty, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5:East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993]

Nias is a kabupaten (regency) within Indonesia’s North Sumatran Province. Its thirteen subdistricts (kecamatan) each contain an average of about fifty villages. In many areas, villages were traditionally organized into federations known as öri, which regulated exchange rates and interest on loans and within which warfare and headhunting were prohibited. After Indonesian independence, the öri were renamed negeri and were formally dissolved in 1967. Before the Dutch “revival” of the öri system, the central region lacked any political authority above the village level and had no paramount chief until one was imposed by the colonial administration. Village leadership there was informal and fluid, as prominent men from different lineages competed for influence. In the south, by contrast, authority traditionally rested with the senior nobleman, the balö zi’ulu, who governed in consultation with councillors or elders. The roles of traditional chief and state-appointed village headman overlap to some extent.

Serious crimes are now handled by government authorities. Disputes concerning customary matters—such as bride-wealth, adultery, or land boundaries—are addressed through extended deliberations led by elders and chiefs, with the goal of restoring social harmony and reaching consensus rather than simply imposing punishment. Settlements often involve fines paid in pigs and gold, accompanied by a communal meal. Violations of church regulations, including polygyny or prohibited funeral feasts, are sanctioned through expulsion from the church and denial of the sacraments.

Nias Family and Marriage

Household organization ranges from the nuclear family, which functions as a basic unit of production and consumption, to extended joint families composed of brothers, their sons and grandchildren, and incoming wives. In central Nias, an entire local lineage may occupy a single large house, divided into separate family quarters but sharing a common social space.

Bride-wealth (böli niha, bövö) consists of as many as thirty named prestations, mainly in gold and pigs, financed through loans from agnates and neighbors. Recipients include members of the bride’s lineage as well as the agnates of her mother, maternal grandmother, great-grandmother, and so on. Together, these groups constitute a chain of affines collectively regarded as wife givers, whether directly or indirectly, to the groom. As wife givers, they occupy a ritually superior position and are owed lifelong allegiance and tribute at ceremonial occasions. Because women may not be exchanged reciprocally, affinal relations are inherently asymmetric. In the south, the preferred marriage is with a matrilateral cross-cousin, although there is no terminological prescription. Postmarital residence is usually patrilocal, though alternative arrangements—such as uxorilocal residence, polygyny, bride-service, and widow inheritance—are also recognized. Divorce is uncommon.

Infants are cared for by all members of the household, including older siblings, and gender-based divisions of labor begin in early childhood. Full moral responsibility and social adulthood are achieved only through marriage and parenthood. Valued male qualities include filial piety, eloquence, firmness, and initiative, while women are expected to demonstrate chastity and diligence.

Inheritance is strongly patrilineal: sons receive nearly all property, though local rules vary regarding the effects of seniority and personal merit. In some areas, uxorilocal sons-in-law and sisters’ sons may also inherit if they have proven loyal and generous allies to the deceased.

Nias Villages and Homes

Villages in culturally distinct southern Nias have traditionally been bigger than the ones in the north. Typically centered around a large house belonging to the chief , with very wide, straight cobblestone streets, they have traditionally been built on high ground for defensive purposes and then surrounded by stone walls and reached by steep steps. [Source: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, East and Southeast Asia” edited by Paul Hockings (G.K. Hall & Company, 1993) ~]

In the central region around Gomo, in the southeast) villages have similar layout, but rarely exceed fifty houses. These settlements are often strategically located on hilltops, though the area also includes small, loosely organized clusters of dwellings and scattered temporary homesteads. In the north, villages may be either compact or dispersed but typically contain no more than twenty to thirty houses.

Security gates were placed in village walls. There were only two entry points to the village, both of which were accessed via steep staircases. These gates led to a straight, paved avenue running through the village center. A row of traditional houses lined the sides of the avenue. Near the village's main square was the home of the village founders, the Omo Sebua. In Nias villages, the space in front of each house belonged to its inhabitants. This "front courtyard" was used for everyday activities, such as drying harvests before storing them. [Source: Wikipedia]

Mario Alain Viaro wrote: The Niha protected their villages by locating them on steep slopes or by surrounding them either with multiple rows of stinging bushes or by a moat, lined with earthen ramparts and blocks of stone. Village gates were customarily closed at night and, to this day, a night sentry keeps watch over the town to warn against fires or unwanted incursions. This bellicose environment permeates throughout Niha social and political structures. [Source: Viaro, Mario Alain, “Ceremonial Sabres of Nias Headhunters in Indonesia” , Arts et cultures. 2001, vol. 3, p. 150-171]

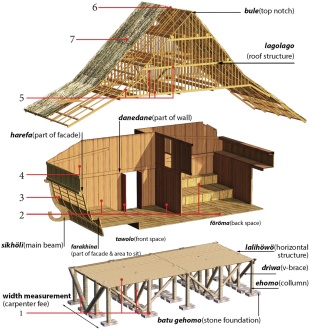

Houses in the south are lovely rectangular structures raised on high pillars with roofs of sago thatch up to 20 meters high. Some have steep sloping roofs and trapdoors that let in ventilation and light. A shortage of wood and high construction costs have meant that these houses have been replaced by simple houses made from wooden planks or concrete. Stone monuments that used to be raised in every village are no longer erected. In the north houses are generally freestanding structure built on stilts, Houses in the south are built side by side around central courtyards. The frames are slotted and bound together without using any nails. ~

Nias Islander Life, Tools and Clothes

Women have traditionally performed domestic chores, tended gardens, weeded fields, and prepared pig food. Men traditionally cleared forest for swiddens, hunted, fished, and spent much time in customary transactions. Planting in many areas is done by teams, who receive payment in rice and pork. [Source: Andrew W. Beatty, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5:East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993]

Nias people produce household objects carved with zoomorphic, floral, or geometric motifs. These include: Bari gana'a (A miniature jewellery box), Bowoa Tanö (Clay pot), Doghi (North Nias); fogao, dröghija (South Nias) (A wooden coconut grater used to grate coconut meat to produce coconut milk or coconut oil, an important ingredient in Nias cuisine.), Figa lae (Banana leaf used as plates), Halu (A paddy pounder), Haru (A wooden spoon, the base of the handle is carved with various forms e.g. a fist.), Katidi (Weavings from bamboo), Lösu (Mortar and pestle), Niru (A tool to separate rice from its husk), Gala (Tray-like item made of wood), Sole Mbanio (A drinking container made from coconut shell) and Tumba, lauru (A tankard used to weigh rice).

Among noteworthy Nias islanders clothing and ornaments are Fondruru, men's earring made of precious metal; Kalabubu, also known as the headhunter's necklace; Nifatali-tali, a necklace of precious metal; Nifato-fato, a men's necklace of precious metal; and Suahu, a comb of wood or precious metal. The kalabubu is traditionally only worn by those who already performed the headhunting activities.

Traditional Nias proverbs: 1) Hulö ni femanga mao, ihene zinga ("Like a cat that eats, starting from the sides"); 2) When doing something, start from the easiest to the difficult; 3) Hulö la'ewa nidanö ba ifuli fahalö-halö ("Just like chopping the water, it will still remain"): Something that is inseparable; 4) Abakha zokho safuria moroi ba zi oföna ("The wound is more severe at the later stage than the beginning"): A course of action can be felt the most towards the end.

Nias Food and Feasts of Merit

Common Nias foods and dishes include: Godo-godo (Shredded cassava shaped into balls for boiling, and later with added coconut flakes), Gowi Nihandro or Gowi Nitutu (Pounded cassava), Harinake (Minced pork), Köfö-köfö (Minced fish meat shaped into balls to be dried or smoked), Ni'owuru (Salted pork for longer storage), Gae Nibogö (Grilled bananas), Rakigae (Fried bananas), Kazimone (Made of sago), Wawayasö (Glutinous rice), Tamböyö (Ketupat), löma (Lemang), Gulo-Gulo Farö (Candy made from distillate coconut milk), Bato (Compressed crab meat shaped into balls for longer storage as found on Hinako Islands), Nami (Salted crab eggs for longer storage, sometimes for months depending on the quantity of salt used), Tuo nifarö (Palm wine) and Tuo mbanua (Raw palm wine with added laru, roots of various plants to give a certain amount of alcohol). [Source: Wikipedia]

Mario Alain Viaro wrote: “Festive practices continue to be essential elements in the social structure and aesthetics of the Niha. Many authors at the turn of the twentieth century mention a particular type of festivity, the “feasts of merit”, under which title the Niha categorise all feasts that involve the ostentatious outlay of pigs and the erection of a megalith, practices still witnessed today. Festive cycles in the south include up to eleven feasts for the “si’ulu”. The “sato”, or non-nobles, gained access only to the first levels. Among these feasts, two demanded heads. The first celebrated the construction of a chief’s house (“folau omo”), which allowed those thereafter to be called “omo lasara”. The second was the funeral ceremony of a chief or, sometimes, a “si’ulu “or a noble person, whose tomb was decorated by a “lasara, “or an effigy. Informants mention no other festivities that required heads, although some may have incorporated head-taking in the past, as the series of festivities varied from village to village. The festive cycles in the north were directly related to the process of founding the “öri”, and do not appear to have required severed heads. [Source: Viaro, Mario Alain, “Ceremonial Sabres of Nias Headhunters in Indonesia” , Arts et cultures. 2001, vol. 3, p. 150-171 =]

“As a result of earlier and more intense missionary activity and colonisation in the north, headhunting in this region was the first to disappear in Nias. Festive practices in the island’s centre can include up to ten feasts. Each man has the possibility of accomplishing not only one “owasa “but all the others, including feasts of the highest levels. A stone monument is erected at each celebration and can reach up to six monuments at one time. Such occasions required that golden ornaments be made (fig. 8) and two heads, one male and one female, be buried at the foot of the largest stone to honour the celebrant and, as required by tradition, “to prevent the “behu “from falling”. Heads were also necessarily part of the inauguration of the “harefa”, a stone terrace where justice was dispensed. Two heads were imperative for a chief’s funeral ceremony. It is only in the centre of the island where one finds such an abundance of stones and, thus, severed heads for as many honoured individuals. “ =

Nias Agriculture and Economic Activity

Gunung Sitoli is the only major town on Nias. It maintains regular maritime trade links with Sumatra and serves as the island’s principal market for cash crops as well as the main source of imported goods. A tourist industry has developed in the south. Coastal populations, who are predominantly Muslim, rely largely on fishing from outrigger canoes. The great majority of Niasans, however, depend on agriculture and pig husbandry for their livelihoods. [Source: Andrew W. Beatty, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5:East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993]

Staple crops include sweet potatoes, cassava, and rice, grown mainly in swiddens and gardens using traditional methods; plows, draft animals, and chemical fertilizers are generally not employed. Wet-rice cultivation is limited by hilly terrain and low levels of agricultural technology. Primary forest is now scarce, and shortened swidden cycles caused by land pressure have reduced yields. Cash crops include coffee, raw rubber, cloves, patchouli oil, and copra. Although all commodities are integrated into the market economy, traditional rates of exchange among pigs, gold, and rice continue to be observed in some areas for customary transactions. In central Nias, where feasts of merit remain important and bride-wealth payments are exceptionally high, a prestige-based economy rooted in reciprocity persists alongside modern economic influences. Hunting wild pigs is still practiced in many regions. Overall, Nias is among the poorer areas of Indonesia, especially in comparison with Sumatra and much of the archipelago.

Trade is conducted largely through small weekly markets serving clusters of villages. These markets provide outlets for surplus agricultural products and sustain small-scale traders who obtain goods from the main town. Niasans are renowned for their industrial arts, particularly their skill in house construction, which has produced some of Southeast Asia’s finest traditional domestic architecture. Locally made bark cloth has long since been replaced by imported clothing, though mats and baskets continue to be produced in villages.

Land tenure arrangements vary widely, but a common distinction exists between original landholders and later settlers. Settlers typically lack the right to sell or transfer the land they cultivate or to plant coconut trees, which symbolize permanent ownership. In the south, communal village ownership of land, with allocation by the chief, has been reported. In the north and central regions, land rights usually belong to the individual who first cleared the land and are inherited by his descendants or lineage. Within lineages, segments or nuclear families work specific plots. Forest land or land left fallow for more than twenty years may be claimed by anyone.

Nias Culture and Art

The Nias have traditionally performed war-dances and their thrilling version of the high jump in which men leap over a two-meter-high stone wall. In the old days the walls were topped by pointed sticks. That is no longer the case. The jumping was used for training. The wars dances were to get psyched up for battle. Now they are performed mostly for tourists. Leaping over the rock is called Fahombo. The war dances are named Fatele or Faluya or Faluaya. Other dances and ceremonies include Maena (Group dance), Tari Moyo (Eagle dance), Fangowai (Welcoming of guest dance) and Fasösö Lewuö (Bamboo competition among young men to test one's strength). [Source: Wikipedia]

Statues have traditionally been an important element of the spiritual life in the Nias islands. The Nias used to produce fine wooden statues, stones columns and limestone seats with animal heads that were associated with their traditional spirits, but now they no longer produce or keep these statues because of beliefs that they are associated with Satan. Some are made for tourists. Many of the finest pieces can be found in museum around the world. [Source: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, East and Southeast Asia” edited by Paul Hockings (G.K. Hall & Company, 1993) ~]

The Metropolitan Museum of Art collection contains a necklace (Nifato-fato, ni 'ohalagae, or kalambagi) from Nias Island. Dated to the late 19th-early 20th century, it is made of gold alloy and is 27 centimeters (10.6 inches) long. Eric Kjellgren wrote: Golden ornaments were among the most prestigious symbols of wealth and status among the Nias Islanders. Large golden ornaments were restricted to the nobility, but commoners were permitted to wear smaller ornaments of a reddish gold alloy. Like the island's monumental stone sculpture, golden ornaments were initially created as ceremonial accoutrements for owasa (feasts of merit), and the scale and splendor of the golden ornaments that an individual was able to commission and wear served as powerful symbols of his or her status. [Source: Eric Kjellgren, “Oceania: Art of the Pacific Islands in The Metropolitan Museum of Art”, 2007]

Crowns, earrings, necklaces, and even false mustaches of gold were among the regalia worn by nobles on all important occasions. Such ornaments as part of chiefty attire were so intimately associated with their owners that they could act as stands-ins when the owner could not be physically present at an event. In Ono Niha cosmology, gold was associated with Lowalangi (the upper world) and believed to be ultimately supernatural in origin, having been first brought to the island in ancient times by a mythological deer.

Its immediate origins were more earthly, for much of the gold used in Ono Niha jewelry was obtained through the sale of slaves to traders from neighboring Sumatra, until the practice was outlawed by Dutch colonial authorities in the early twentieth century. Endowed with potent magical properties, gold was both coveted and dangerous. Newly fashioned gold ornaments were believed to be so "hot" with supernatural power that they had to be ritually "cooled" before it was safe to wear them. In the past, a freshly created set of ornaments for a high noble would initially be worn by a slave, whose body absorbed their destructive energy.- Elegant in its simplicity, this exquisite necklace was once among the treasu res of a noble Nias famil y. Consisting of a broad, tapering crescent of pleated gold with a simple hooked clasp at the back, necklaces of this type were formerly made throughout the island. In Central Nias they were worn by men and called ni'oha/agae, a name that compares their delicate pleats to the subtly ribbed leaves of banana trees. In the north, where they were also a male ornament, they were ca ll ed nifato-fato. In South Nias, however, such necklaces, known there as kalambagi, were worn by both men and women, and their subtle pleats were at times accented with ftoral or geometric motifs.

Nias Ancestor Figures

The Metropolitan Museum of Art collection contains an ancestor figure (Siraha salawa or siraha nomo) made by the people of Tanb Niha, northern Nias Island. Dating to the 19th-early 20th century it is made of wood and is 63.5 centimeters (25 inches) long. Eric Kjellgren wrote Ancestors, especially those of noble families, play a central role in Ono Niha art and culture. The Ono Niha today are Christian, but in the past artists created a variety of ancestor images, known generically as adu, to contain ancestral spirits and to serve as intermediaries between the human and the supernatural worlds.By far the most numerous type was the adu zatua, a relatively small ancestor image, made after an individual 's death to contain his or her spirit, which was affixed to the wall of the house. The detail and artistic quality of these images often varied according to the social standing of the deceased. [Source: Eric Kjellgren, “Oceania: Art of the Pacific Islands in The Metropolitan Museum of Art”, 2007]

Larger, more refined ancestor images were known as siraha salawa or siraha nomo and represented distant and illustrious ancestors, often the founders of noble families and lineages. Noble Ono Niha houses might contain many adu zatua, but each had only a single siraha salawa. Restricted to the aristocracy, the siraha salawa was displayed on a freestanding post in the largest room of the house. The potent ancestor it represented served as the supernatural guardian and protector of the household.

The style of the siraha salawa with the figure in a seated position and grasping a cup firmly with both hands, is typical of North Nias. As befits their exalted status, siraha salawa are shown wearing the elaborate golden crowns and other ornaments that are the prerogative of the highest-ranking nobles. 10 The type and number of these ornaments indicate the gender of the ancestor. In North Nias, male ancestors, like the present figure, are shown with a single earring in the right ear and a single bracelet on the right arm, whereas female ancestors wear matching pairs of earrings and bracelets.

The form of the central peaked crown on the head of this image echoes that of the large golden crowns commissioned by the nobility for owasa (feasts of merit) and afterward worn on special occasions; the projections behind the crown, called ni'o woli woli, depict the coiled fiddleheads of sprouting ferns.

Ono Niha men were typically clean-shaven, and the figure's pronounced facial hair almost certainly represents the ceremonial mustache (bu bawa ana'a) and beard fashioned from gold that were worn by high-ranking men on festive occasions. Around his neck the ancestor wears a kalabubu, a distinctive necklace that marks his prowess as a warrior and,the leader of Tabeloho village, North Nias. Clad in full ceremonial regalia, he wears lavish golden ornaments, including a high-peaked crown and a pleated gold necklace (nifato-fato) that was limited to men who had taken the head of an enemy. Decked in the glittering regalia of an aristocratic warrior, with his compact, muscular body poised as if to spring forward on a moment's notice, this figure embodies all the qualities of the siraha silawa as the revered and powerful protector of a noble house.

Nias Monumental Stone Carving

The people of Nias Island are renowned for their monumental stone carving. The Metropolitan Museum of Art collection contains a Ritual Seat for a Noble (Osa' osa) made from stone by the Ono Niha people. Dating to the 19th century, it originates from the Gomo and Tae River region and measures 68.6×76.8×127 centimeters (27 inches high, with a width of 30.25 inches and a depth of 50 inches)

According to the Metropolitan Museum of Art Much of Nias stone sculpture is commemorative in nature—created to honor members of the nobility, both living and dead. Ritual stone seats (osa' osa) are unique to the central region of the island; they serve as chairs for high-ranking nobles at feasts and other ceremonial occasions, where they are set up near the home of the feast giver as a sign of his or her exalted rank. This example is of a type called "hornbill" (gogowaya), named for a large bird important in many Indonesian and Melanesian cultures. The "hornbill" here is depicted not as a discrete species but as a mythical animal that combines the teeth of a fearsome carnivore and the antlers of a deer with the distinctive beak, crest, and tail of the hornbill. The result is a composite creature, which acts as a fearsome protector of the nobility and their ancestors. [Source: Metropolitan Museum of Art]

Eric Kjellgren wrote The art of Nias Island is notable for the scale and variety of its monumental stone sculpture. Whereas the island's wood figures, typically honored the dead, its stone sculpture primarily celebrated the achievements of the living.' Stone sculptures ranged from immense slabs and pillars to human figures, seats of honor, and raised circular platforms on which noblewomen danced at festivals. [Source: Eric Kjellgren, “Oceania: Art of the Pacific Islands in The Metropolitan Museum of Art”, 2007]

Created to honor nobles of either sex, stone sculptures were commissioned by aristocratic men as part of the ceremonial requirements of owasa (feasts of merit). The owasa consisted of a prescribed sequence of feasts, each of which elevated its noble sponsor to a progressively higher social rank. Each owasa required the slaughter and distribution of large numbers of pigs and the commissioning of the appropriate artworks in the form of stone sculpture and gold ornaments. The stone monuments commissioned for the owasa were erected near the sponsor's house on the central plaza of the village as a permanent symbol of the sponsor's status.

Ceremonial stone seats (osa'osa) depicting fearsome supernatural creatures, are unique to Central Nias. Probably originally inspired by large zoomorphic sedan chairs (also called osa'osa) made from wood and used to carry nobles on festive occasions, the massive stone seats were carried on ly once during the owasa for which they were created and afterward served as stationary seats of honor for high-ranking aristocrats at feasts and other important occasions. Ono Niha stone carvers produced several varieties of osa'osa, which often have multiple names, describing their form and imagery.

The work at The Met is known by three names, each of which emphasizes a different aspect of its nature. Broad ly speaking, it is a si sara bagi; this name indicates that the creature depicted has one (as opposed to three) monstrous heads.9 It is also called a gogowaya (hornbill); this large forest bird was symbolic of Lowalangi (the upper world) in Ono Niha cosmology. However, the hornbill here is depicted not with the features of a single species but as a mythical animal that combines the legs and teeth of a feline or crocodile (a creature associated with the underworld, Latu re Dano) with the antlers of a deer and the beak, crest, and tail of a hornbill. The result is a monstrous composite beast, whose disparate anatomy unites the upper world and the underworld to create a ferocious supernatural guardian for its noble occupant, a role emphasized by the warrior's necklace (kalabubu) that it wears around its throat. This type of osa'osa is also called a /ae/uo (the leaves in the sun), a metaphorical reference to its aristocratic sponsor whose personal resplendence illuminates the village like sunlight shining on the leaves of trees.

Nias Megaliths: See Separate Article: NIAS ISLAND: MEGALITHS, UNIQUE PEOPLE, SURFING factsanddetails.com

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, Nias Heritage Museum

Text Sources: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East / Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993; National Geographic; New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Lonely Planet Guides, Library of Congress, Smithsonian magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Reuters, AP, AFP, Wikipedia, BBC, CNN, and various books and other publications.

Last Updated December 2025