NIAS PEOPLE

The Nias people live on the island of Nias and other islands near it off the west coast of Sumatra. Also known as the Niasan, Niasser Ono Niha, and Orang Nias, they have a reputation for fierceness and traditionally had a militaristic culture which is one of the reasons Nias has resisted the impact of foreign influences for so long. The warrior culture of Nias goes back for centuries when local villages would band together in coalitions and declare war on each other. Inter-village warfare was fierce and furious, provoked by a desire for revenge, slaves or human heads.

The traditional homeland of the Nias people is the island of Nias. They also live on the Batu Islands (which were settled from South Nias) and Hinako off the west coast of Nias. The Nias have traditionally farmed sweet potatoes, cassava and rice and fished with outrigger canoes. The name "Nias" is probably a foreign corruption of the indigenous name for the island, "Tanö Niha" (the land of men). [Source: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, East and Southeast Asia” edited by Paul Hockings (G.K. Hall & Company, 1993)]

Anthropologist Mario Alain Viaro wrote: “ Situated on the borders of the Javanese Empire, the last bastion of Asia before the vast expanse of the Indian Ocean, Nias Island has produced a civilisation noted for its complex social structures and architecture, wooden and stone statuary, and remarkable weaponry. [Source: Viaro, Mario Alain, “Ceremonial Sabres of Nias Headhunters in Indonesia” , Arts et cultures. 2001, vol. 3, p. 150-171]

RELATED ARTICLES:

NIAS ISLANDERS: LIFE, CULTURE, SOCIETY factsanddetails.com

NIAS ISLAND: MEGALITHS, UNIQUE PEOPLE, SURFING factsanddetails.com

Nias Language

Nias belongs to the Western Malayo-Polynesian Branch of the Austronesian Language Family. It has been linked with Mentawai and Toba Batak languages. The Nias alphabet differs from the Indonesian alphabet. Several Indonesian letters are not used, while additional letters with unique symbols represent sounds not found in Indonesian. The Nias alphabet uses both uppercase and lowercase letters and consists of the following:Aa, Bb, Dd, Ee, Ff, Gg, Hh, Ii, Kk, Ll, Mm, Nn, Oo, Öö, Rr, Ss, Tt, Uu, Ww, Ŵŵ, Yy, Zz Examples of Nias vocabulary and their Indonesian equivalents are available in the List of Nias Swadesh. [Source: Andrew W. Beatty, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5:East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993; Wikipedia]

The Nias language is commonly described as having three main dialects: 1) the northern dialect spoken in Gunungsitoli, Alasa, and Lahewa in North Nias; 2) the southern dialect used in South Nias; and 3) the central dialect spoken in West Nias, especially in the areas of Sirombu and Mandrehe.

However, the 1977–1978 Indonesian and Regional Language and Literature Research Project of North Sumatra proposed a more detailed classification, identifying five dialects: 1) the northern dialect spoken in Alasa and Lahewa; 2) the Gunungsitoli dialect; 3) the western dialect spoken in Mandrehe, Sirombu, and the Hinako Islands; 4) the central dialect found in Gido, Idano Gawo, Gomo, and Lahusa; and 5) the southern dialect spoken in Telukdalam, Tello Island, and the Batu Islands. Despite these distinctions, mutual intelligibility among the dialects is high, with similarities estimated at around 80 percent.

The Bible was translated into a northern dialect, and this has become the standard form. Bahasa Indonesia, the language of government bureaucracy and education, is not widely known among ordinary villagers.

Nias People Religion

Nias people have traditionally been animists and ancestral worshippers, although the majority are now Christian. According to the Christian group Joshua Project 90 percent of Nias Islanders are Christians, of whom about 80 percent are Protestants and of these 10 to 50 percent are Evangelicals. About five percentof the total population are Catholics and five percent are Muslims. Affiliation to an official religion is compulsory under Indonesian law. [Source: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993]

Elements of traditional religion have endured in the form of concepts about sin and merit and the use of healers to deal with matters related to spirit possession. Nias feasts of merit are intended in part to win the blessings of local fertility gods. Only men who have hosted enough feasts get full burial honors. ~

The first Christian missionaries visited Nias in 1865, but Christianity did not really catach on until the early 1900s when the Dutch established control of the island and then grew rapidly and was spread with the help of local ministers. Christianity made great inroads among the Nias beginning in 1915 through apocalyptic conversions movements known as the Great Repentance that characterized traditional Nias beliefs as works of the devil.

The ethos of social life was rooted in a non-Christian system of values, and elements of spirit belief persisted. Feasts of merit were held in part to obtain blessings and fertility from wife givers, who occupied a position analogous to that of gods. In traditional cosmology, the creator god Lowalangi ruled the upper world, while his younger brother, Lature Danö (also known in the central region as Nazuva Danö), governed the lower world. There was also a priestly cult devoted to the goddess Silewe. Daily well-being depended on appeasing patrilineal ancestral spirits and securing the favor of wife givers, while ultimate destiny rested with Lowalangi, who was believed to keep humans as his pigs. Sacrifices to forest spirits ensured success in hunting. Clan totems were unknown.

Traditional ritual specialists, known as ere (men or women), conducted life-cycle ceremonies, divination, and healing. They mediated between humans, ancestral spirits—represented in carved wooden figures—and God in various manifestations. Some ere were also skilled reciters of oral traditions. Leaders of later conversion and revivalist movements were often former ere, and Christian evangelists frequently claimed similar oracular abilities, though reframed within a Christian context.

Only men who had sponsored feasts of merit, repaid all associated debts, and received full funerary rites—including human sacrifice—were believed to enter the Golden Paradise, tete holi ana’a, envisioned as a replica of the earthly village. Ordinary men were thought to be denied this fate and instead left to decay, “becoming food for the worms.”

First People on Nias Island

Nias is an ancient land whose early history remains largely unknown. The origins of the Nias people are still unclear, although striking cultural similarities link them to the Batak, Toraja, Ngaju Dayak, and other peoples of eastern Indonesia, all of whom belong to related language families. Comparable social systems are also found among highland societies of mainland Southeast Asia, such as the Kachin, Chin, and Naga. Some scholars have suggested a diffusion of so-called megalithic cultures from Assam, but further comparative research is needed to support such reconstructions. Nias origin myths locate the beginning of human life in the central part of the island, and clan genealogies ultimately trace descent to a small number of ancestral founders. The island’s considerable cultural diversity therefore cannot be easily explained by theories of multiple, separate waves of migration. [Source: Andrew W. Beatty, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5:East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993; Viaro, Mario Alain, “Ceremonial Sabres of Nias Headhunters in Indonesia” , Arts et cultures. 2001, vol. 3, p. 150-171]

Although no definitive evidence exists for how long humans have inhabited Nias, local tradition holds that life began along the Gomo River, where six gods descended to earth and gave rise to humanity. This belief underlies the Nias self-designation ono niha, meaning “children of the people.” From Central Nias, populations gradually spread northward and southward, developing distinct regional languages, customs, and artistic traditions.

Archaeological research since 1999 indicates that Nias Island has been inhabited for at least 12,000 years, with possible human presence dating back as far as 30,000 years, likely through migrations from mainland Asia during the Paleolithic period. Similarities with the Hòa Bình culture of present-day Vietnam suggest early origins in mainland Southeast Asia. [Source: Wikipedia]

More recent genetic studies, however, show that the present-day Nias people are Austronesian in origin, with ancestors likely migrating from Taiwan through the Philippines around 4,000–5,000 years ago. Genetic analysis of modern Nias populations reveals close similarities to Taiwanese Indigenous and Filipino groups, low genetic diversity indicating a historical population bottleneck, and no genetic continuity with the island’s earliest inhabitants or with Andaman-Nicobar populations. While Austronesian migration is clear, the exact direction and sequence of these movements remain uncertain.

Early Nias History

Despite its remote location, Nias was not historically isolated. Archaeological and historical evidence suggests early contact with traders from the Middle East, mainland Asia, and later Europe, pointing to the island’s participation in long-distance trade networks from an early period. Cultural affinities further link the Nias to the Batak of Sumatra, the Naga of India, Dayak groups in Kalimantan, and Indigenous peoples of Taiwan. In the past, Nias society was marked by inter-clan warfare and headhunting, practices associated with funerary rites and marriage obligations.

Written records of Nias date back to the era of maritime trade connecting Baghdad, India, China, and Southeast Asia. The earliest known reference appears in the account of Suleyman in 851, who described the island as rich in gold and noted customs involving coconut cultivation, palm wine production, body oiling, and headhunting in connection with marriage and polygyny.

Subsequent accounts include The Book of Indian Wonders (Kitab ʿAjaʾib al-Hind), dated to around 950; the writings of the geographer al-Idrisi (1154); descriptions by al-Qazwini (1203–1283); reports by Rashid al-Din (c. 1310); and references to a large island city by Ibn al-Wardi in 1340. Together, these sources attest to Nias’s long-standing presence in the historical consciousness of the wider Indian Ocean world.

Throughout its history, the Chinese, Portugese as well as Arab traders have all explored Nias. The island became known as a source of slaves with the Acehnese, Portuguese and Dutch all probably having bought slaves from here at one time or another. In fact, up until the 19th century Nias’ only connection with the outside world was through the slave trade.

Later Nias History

Before Dutch intervention, the only significant external contact recorded for Nias was with Acehnese slave traders. These traders brought gold, the most prestigious object in Nias society, which was essential for bride-wealth payments and feasts of merit. The slave trade caused severe depopulation in many areas of the island and was not effectively curtailed until the modern period. [Source: Andrew W. Beatty, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5:East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993]

During the nineteenth century, Nias became widely known as a center of the slave trade. Although the island was not completely isolated from the outside world, it nonetheless preserved its distinctive culture with remarkable resilience, largely bypassing the Indian, Islamic, and European influences that transformed much of Asia. For this reason, some historians and archaeologists regard Nias as one of the few surviving examples of a living megalithic culture.

In 1857, Nias was nominally placed under Dutch colonial authority, but it remained peripheral to colonial interests until a shift in policy toward the Outer Islands led to full military conquest in 1906. Traders from Sumatra, some of whom settled in the port of Gunungsitoli, introduced Islam to parts of the coastal population. Christianity arrived earlier, in 1865, through German Protestant missionaries, though it initially gained little following.

Widespread conversion to Christianity did not occur until the early twentieth century, after missionary activity and colonial administration undermined traditional social structures and belief systems. Beginning around 1915, a series of apocalyptic mass-conversion movements swept the island in what became known as the Great Repentance. These movements profoundly reshaped religious life in Nias, redefining traditional beliefs as incompatible with Christianity. The form Christianity takes on the island today, and its complex relationship with indigenous culture, is largely a legacy of this period.

Since Indonesian independence, Nias has experienced limited economic development, the growth of its administrative capital, and increasing centralization of authority away from village-level institutions. Despite more than a century of sustained contact, conflict, and change, traditional Nias culture remains remarkably resilient. The island’s population is still distributed across more than 650 villages, many of which remain difficult to access by road.

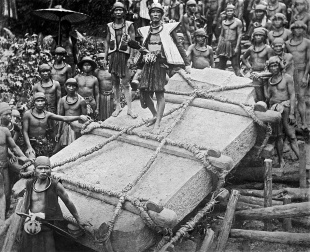

Traditional Nias Warrior Society

Anthropologist Mario Alain Viaro wrote: “Although agriculture had stood its ground and, in the past, was an occupation carried out by either free men or a servile labour force, the Niha have traditionally been warriors. The society gave greater importance to the culture of war 1) and to manufacturing weapons (spears, swords, shields, armour) than to agriculture and making farm tools; and to constructing defensive structures rather than sowing crops. The Niha protected their villages by locating them on steep slopes or by surrounding them either with multiple rows of stinging bushes or by a moat, lined with earthen ramparts and blocks of stone. Village gates were customarily closed at night and, to this day, a night sentry keeps watch over the town to warn against fires or unwanted incursions. This bellicose environment permeates throughout Niha social and political structures. [Source: Viaro, Mario Alain, “Ceremonial Sabres of Nias Headhunters in Indonesia” , Arts et cultures. 2001, vol. 3, p. 150-171 =]

“Education was warlike and violent. In the south of the island, youths trained very early on to jump over a two-metre-high stone pyramid, or to clear a ditch filled with sharpened bamboo. Passage into adulthood, and therefore incorporation into society, traditionally required young warriors to take heads. In exchange for this act, a Niha chief bestowed on the successful headhunter the title of “iramatua “(warrior) and gave him the “calabubu “necklace during a time of festival. Only after this investiture would the young warrior take part in the “orahu “gathering of village men and in the “owasa “ceremonial cycle of pig-trading. Included in the “owasa “is jewellery-making, where gold ornaments provide men access to positions of rank in accordance with clan rules. “ =

Nias Headhunting and Slave Raiding

Prior to Dutch colonization, warfare and headhunting between villages or village clusters were endemic. Heads or human sacrifices were required for funerals and certain feasts of merit. The slave trade with Aceh led to increased insecurity. Mario Alain Viaro wrote: “Before Dutch colonisation, the hunt for slaves was a fundamental part of the warrior and chieftain society in Nias. Although slave traffic before the seventeenth century was limited to Sumatra and Aceh, the arrival of European merchants in the region created a much greater demand for them. This growth in the market, which now extended to Batavia and the Bourbon Island, must have brought about a multiplication in the number of raids and, consequently, an increase in trading revenue for the island’s chiefs. [Source: Viaro, Mario Alain, “Ceremonial Sabres of Nias Headhunters in Indonesia” , Arts et cultures. 2001, vol. 3, p. 150-171 =]

One can suppose that owning slaves, once a privilege for a few powerful chiefs, became a prerogative of numerous noblemen and created greater competition in the trade. This hypothesis is supported by an increased number of monuments erected during the nineteenth century, both in the south and centre of Nias.3 Parallel to the growth in slave traffic was the increase in the scale of headhunting, to the further detriment of the poor and delight of the privileged, and—in this author’s opinion—an early stage of globalisation. Figures obtained by foreign visitors at that time enable us to form an idea of the extent of these changes.

“One of the (endorsed) reasons for waging war against other villages or clans was to procure slaves and to plunder their treasures for gold ornaments. The relation between war and slavery is patently obvious, whether it be from the viewpoint, “we attack to obtain slaves”, or the other way around, “you took slaves from us, therefore we wage war against you as revenge and to take them back to us”. Elio Modigliani, Italian entomologist and author of the first scientific ethnography on Nias (1890), constantly refers to the permanent state of war in Nias. Commodities—their ownership and use in feasts came beyond the reach of the average person—there developed a genuine and profitable market for them. Head-taking was a practice that directly led to the show of power because, like owning slaves, the ownership of heads meant that one had the financial means to acquire them. Heads of enemies killed in battle, as well as those brought in by young warriors, were displayed on the front wall of the assembly house (“bale”). Heads taken that were ordered by a chief were hidden in trees or buried, to await use in later festivities. This contradicts the old idea that heads were used for sacrifice, whose climax was the moment of decapitation. =

“Occasions for which heads were required varied between different regions of Nias Island, but, generally speaking, included the following: 1) When a dying chief requested an honourable funeral (a certain number of skulls would later hang in his house, often those of slaves). 2) When a stone bench (“darodaro”) was laid before the chief’s house. 3) When a chief constructed his house (heads were buried beneath the main supporting pillars). 4) In the last “mobinu “feast, when a big chief, who wished to obtain “ a great name”, invited all his allied villages (a head was buried under the ladder to the house and, after two months, dug up and cleaned to hang from the roof). 5) When a “bale “was constructed, a site where the statues of the village “gods” would be kept. 6) When a new village was founded (“fondrakö”). 7) When healing was requested in cases of grave illness. Additionally at these feasts, as at others where beheading was not required, the chief would demonstrate his power by appearing before the people and his allies in full splendour, wearing the gold ornaments of his rank and bearing his ceremonial sabre. =

Nias Weapons and Headhunter Swords

Mario Alain Viaro wrote: “Mastery in the fabrication of arms (knives, sabres, and swords) is recognised throughout Indonesia. Fine examples of this proficiency are found in the sabres of Nias. Although there is no iron ore in Nias, the Niha acquired the metal through commercial exchange with traders who docked at the island’s bays. Like gold, copper, and tin, iron was considered a precious metal. As Nias Island has been intermittently cited since the ninth century in Arab and Chinese accounts and, later, in the seventeenth century by Europeans, it can be argued that the production of iron weaponry began at least a thousand years ago. There is reason to believe that the type of warrior society characteristic of the Niha has remained, more or less, unchanged since these remote times. [Source: Viaro, Mario Alain, “Ceremonial Sabres of Nias Headhunters in Indonesia” , Arts et cultures. 2001, vol. 3, p. 150-171=]

“The machete or knife (“balatu”) is the Niha weapon “par excellence”. It is not only a technical marvel and a powerful weapon, being very light and well balanced, but also a “sculptural chef-d’oeuvre “with respect to its handle. Called “balatu ide “in the south and “si oli warasi “in the north, it is used for both domestic chores and work in the fields or forests. Every man always carries one with him. The blade has only one cutting edge, with the point curving towards the top or the bottom, depending on the model, and the blade becoming thicker and wider at its extremity. The sheath is made of two wooden parts hollowed out to make room for the blade. These two parts are joined together using braided rattan or copper bands.” =

Viaro describes the ceremonial sabres of Nias headhunters as prestigious weapons distinguished by long blades, copper-covered sheaths, and elaborately carved hilts. These hilts commonly depict the lasara, a hybrid, protective creature combining features of several animals (boar, crocodile, snake, stag), also seen in house façades, tombs, and ritual ornaments. Western scholars have interpreted the lasara in various ways, but locally it functioned as a powerful protective symbol. Some sabres feature a small human or monkey figure identified as bechu zöcha, a dangerous spirit believed to feed on human shadows. When shown biting the lasara, the spirit is transformed into a protective talisman thought to increase the warrior’s strength and ward off misfortune.

In southern Nias, chiefs’ and nobles’ sabres carried a braided rattan ball (raga iföboaya) attached to the sheath, holding amulets such as animal teeth, claws, stones, cloth, and small figures. These objects were believed to grant invincibility, strength, and protection. Warriors were deeply attached to these amulets and feared severe misfortune if deprived of them, especially retaliation from the spirits of slain enemies. Rituals and offerings accompanied the making and use of these talismans, similar to those for ancestor statues. Although their exact meanings were closely guarded, the sabres and their amulets clearly played a central role in warfare, headhunting, and the spiritual protection of Nias warriors.

For the complete article from which the material here is derived see “Ceremonial Sabres of Nias Headhunters in Indonesia” by Alain Viaro, 2001 academia.edu

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East / Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993; National Geographic; New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Lonely Planet Guides, Library of Congress, Smithsonian magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Reuters, AP, AFP, Wikipedia, BBC, CNN, and various books and other publications.

Last Updated December 2025