INDONESIAN GOVERNMENT AND MINORITIES

People are identified by their religion on their identity cards, not their ethnic group. Many minorities are administered by the central government to varying degrees down to the district and village levels and below that they govern themselves. The Indonesian government provides schools, police, road maintenance, health post and other basic services. The "unity in diversity" is embraced as the key to Indonesian cohesiveness. This notion was encouraged by the Dutch but grew in importance as Indonesians rallied together for independence from the Dutch.

Indonesia doesn't have one single agency that handles "ethnic group" issues. Ministry of Social Affairs (Kementerian Sosial): Identifies and works with Komunitas Adat Terpencil (KAT) – isolated indigenous communities, focusing on their social welfare. The Ministry of Home Affairs (Kementerian Dalam Negeri) manages general, regional governance, peace, and order, including fostering harmony between different communities at the local level. The National Human Rights Commission (Komnas HAM) is a state-independent body that monitors human rights, including those of indigenous peoples, and pushes for better policy implementation. The Indonesian Heritage Agency (IHA) was established in 2022 and inaugurated as a Public Service Agency in 2023. It is responsible for the management of 18 museums and 34 cultural heritage sites.

Aliansi Masyarakat Adat Nusantara (AMAN) (Indigenous Peoples' Alliance of the Archipelago): is the largest independent organization representing millions of indigenous peoples, advocating for their economic, political, and cultural rights. There are relatively new laws using terms like Masyarakat Adat (Customary Law Societies) to acknowledge indigenous rights. The Constitution acknowledges indigenous rights, and legislation addresses agrarian, human rights, and development issues affecting these communities.

Issue Among Ethnic Groups in Indonesia

Some ethnic groups do not want to share resources found in their land with other groups and don’t want other ethnic groups to settle on their land. In some cases they don’t even like other ethnic groups to come and work.

The government says indigenous people own their land but if often if the government needs the land it simply takes it. It is illegal for ethnic groups within Indonesia to refer to themselves as anything other than Indonesians. People have been killed for possessing a copy of underground magazine speaking out against government policies on minorities or doing things like raising the flag for West Papuan pro-independence groups.

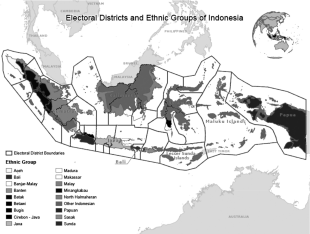

Ethnic relations in the Indonesian archipelago have long been a concern. From the beginning of the republic, Indonesian leaders recognized the possibility of ethnic and regional separatism. In the 1950s and early 1960s, war was waged by the central government against separatism in Aceh, other parts of Sumatra, and Sulawesi, and the nation was held together by military force. [Source: Clark E. Cunningham, Countries and Their Cultures, Gale Group Inc., 2001]

There has been a call to bring back the sultanate system as a way of strengthening local identity.

Suharto and Minorities

Indonesia's harmonious mix of cultures was fostered by the Suharto dictatorship. Under Suharto, no one was allowed to preach hatred or racial intolerance. But many felt that ethnic tensions bubbled below the surface. Suharto was accused of creating unity with a shallow, artificial nationalism. Indonesia's film maker Garin Nugroho said, "We lost our regional identities with replacing them with something. The government forced society into limbo, into 'unity,' which was just homogeneity by violence and manipulation. And this became a time bomb." See Pancasila.

Suharto—and Sukarno before him—attempted to stifle religion and ethnic intolerance by promoting a strong sense of national unity with a common language and the national philosophy of Pancasila. The power of Suharto's military was enough to intimidate most rival ethnic groups into getting along, at least superficially. Provincial governors were appointed from Jakarta and the military was a major presence in most cities, towns and villages.

But, Richard Lloyd Perry wrote in the Independent, “Rather than eliminating ethnic and religious differences, Suharto froze them, forcing unity and sniffling dissent with repressive military apparatus...Only in the last few years has it become obvious what an illusion that was." Lug Ketut Suryani, a psychiatrist and Bali activist told the Washington Post, "Having a multiethnic culture means we are all Indonesians. But Suharto tried to make us all uniform, so you can't differentiate Jakarta from Surabaya from Denpesar...We say that colonialism now comes from our own people...We feel like a stepchild."

Transmigration

Transmigration has been a scheme in which mostly poor and landless people in Java and other overpopulated islands have been resettled in Indonesia's frontier areas with free house lots, supplies and other incentives. Transmigration was started 1905 by the Dutch, who, moved 650,000 people most from Java to Sumatra. The policy was continued by Sukarno and accelerated under Suharto with financial support from the World Bank, who put up $5 billion for the project.

More than 8.5 million people were moved from densely populated areas, primarily in Java, to Sumatra, Kalimantan, the Moluccas, and West Papua (Irian Jaya, on New Guinea) during the main transmigration period between 1969 and 1994. More than 3.2 million were resettled when the program was its peak between 1984 and 1989. About 5.5 million people have participated in official transmigration schemes. Unassisted migration has accounted for another two million.

"Transmigration is necessary," a teacher, who migrated to West Papua (Irian Jaya, on New Guinea) from Java told the New York Times, "because more than half of Indonesia's population lives in Java, while Kalimantan and West Papua (Irian Jaya, on New Guinea) are empty." In addition to helping ease population pressures on Java, transmigration has provided timber and mining companies in Kalimantan and West Papua and elsewhere with a ready supply of labor.

See Separate Article: TRANSMIGRATION IN INDONESIA: HISTORY, SETTLERS, PROBLEMS factsanddetails.com

Changing Indonesia’s Citizenship and Autonomy Laws

Thomas Fuller wrote in the International Herald Tribune, “The country has redefined what it means to be a "native." A citizenship law passed in 2006 proclaims that an indigenous Indonesian is someone who was born here to Indonesian citizens, a radical departure for a society that separated the Chinese in one way or another through colonial times and more recently during Suharto's 33-year reign that ended just after the riots in 1998. Other laws have erased the preferential treatment for "pribumi," or indigenous groups, in bank lending and the awarding of government contracts, a policy that still exists in Malaysia, where racial tensions are creeping higher. "The situation of the Chinese has never been as good as today," said Benny Setiono, head of the Chinese Indonesian Association, a nonprofit group that represents the community. "We feel more free, more equal." [Source: Thomas Fuller, International Herald Tribune, December 14, 2006 +]

“The horrors of the anti-Chinese violence in 1998 were the prime impetus for the legal overhaul. But Indonesians also realized that espousing the concept of a "native" could be explosive for everyone, not just the Chinese. "The question of who was here first became very dangerous," said Andreas Harsono, a journalist who is researching a book on nationalism here. "The logic has been manipulated by many politicians." The so-called transmigration policies of Suharto dispersed hundreds of thousands of families, mainly Javanese, across the archipelago, creating conflicts with other ethnic groups. Today, instead of using the word "pribumi," some politicians claim they are "putra daerah," or local sons, and contrast that with "pendatang," or newcomers. A country that sometimes seems to have as many ethnic groups and dialects as inhabited islands (about 6,000) will probably never be clear of racial rivalries, but tensions are nowhere near the levels of a few years ago. +\

B.J. Habibie and Abdurrahman Wahid—the two presidents that followed Suharto—made some efforts to give the provinces in Indonesia more control of their own affairs. Special Autonomy Laws were set up to give indigenous people more say in their affairs were passed under Habibie in 1999. The laws were passed mainly to keep East Timor from demanding independence but had a an impact to places like Aceh in northern Sumatra and West Papua (Irian Jaya, on New Guinea).

The laws affected 26 of Indonesia’s 27 provinces and were viewed as a move towards making Indonesia a federalist state like the United States. The laws gave the provinces more authority over all matters except defense, foreign policy and judicial, fiscal, monetary and religious affairs and matters deemed ‘strategic.” Six new provinces were officially created in 2001: North Maluka, Maluka, West Irian Jaya (later West Papua), East Irian Jaya (New Guinea), Banten (previously part of West Java) and Banka-Belitung (once part of South Sumatra Province). The move was made to ease ethnic tensions in these provinces, give them more autonomy and say over how their resources were exploited. They also had to take on more responsibility.

Malaysia Verus Indonesia on Race Policy

Thomas Fuller wrote in York Times: “Indonesia and Malaysia have much in common: language; a border that slices across Borneo; overlapping ethnic groups. But the two countries are moving in opposite directions on the fundamental question of what it means to be a "native." With a new citizenship law passed this year, Indonesia has redefined "indigenous" to include its ethnic Chinese population — a radical shift from centuries of policies, both during colonial times and after independence in the 1940s, that distinguished between natives and Indonesia's Chinese, Indians and Arabs. Malaysia, meanwhile, is sticking to its longstanding policy that Malay Muslims, the largest ethnic group in the country, are "bumiputras," or sons of the soil, who have special rights above and beyond those of the country's Chinese and Indian minorities. Maintaining this controversial policy has led to what one commentator calls a retribalization of Malaysian politics, with rising assertiveness on the part of the country's Malay Muslims. [Source: Thomas Fuller, New York Times, December 13, 2006]

“Both Indonesia and Malaysia have suffered race riots in recent decades. Indonesia's were much bloodier and more far-flung. Yet today, ethnic tensions are more likely to make headlines in Malaysia than Indonesia. Malaysia's Chinese community was angered by the demolition of a Taoist temple in Penang. Both Muslims and non-Muslims are upset about a series of disputes over whether Shariah or secular law should take precedence....Paradoxically, some in Malaysia, which has long been wealthier and more politically stable, are looking admiringly at developments in Indonesia. Azly Rahman, a Malay commentator on the widely read Web site Malaysiakini, said poor Indians and Chinese are neglected under the current system. "A new bumiputra should be created," he said. "Being a Malaysian means forgetting about the status of our fathers. We need affirmative action for all races."

Ethnic Troubles in Indonesia

The combination of economic distresses, a breakdown of law and order and the release of pent up aggression resulted a wave of ethnic violence before and after Suharto resigned in May 1998. There were some concerns at that time that Indonesia would become Balkanized (divided into warring states) like Yugoslavia. Ethnic troubles, population growth and other reasons produced more than 1 million internally displaced refugees in 2001, 10 percent of the world’s total.

Many non-Javanese shudder at the idea of being told what to do by the Javanese. The Indonesian government does little to help ethnic groups displaced by violence and fear of violence other than evacuate them and dump them some place, where the provincial governments are left to take care of them.

A key characteristic of Suharto’s New Order regime was the prevalence of security and order throughout the nation. Any outbreak of violence between ethnic or religious groups was quickly and sternly repressed. Tensions simmered below the surface, however, and after Suharto’s fall in 1998, ethnic and religious conflict erupted in several regions. Security forces were initially ineffective in regaining control because the police, poorly trained, poorly equipped, and understaffed, were ill prepared to handle large-scale unrest. The TNI, stung by accusations of human-rights abuses, and resentful of the change in mission responsibility, was reluctant to intervene without a formal request for assistance from local authorities. [Source: Library of Congress *]

Ethnic Violence in Indonesia

In Kalimantan Barat Province, the relative harmony that had prevailed among native Malays, ethnic Chinese, and Dayaks for generations was upset by the influx of hundreds of thousands of Madurese under the Transmigration Program in the 1970s and 1980s. Communal violence in the 1990s was triggered by Dayak discontent with the Madurese community’s hold on the economic balance of power in the region, and by a perception that the Madurese were illegally taking Dayak land. Hundreds of settlers were killed in the Sambas area of Kalimantan Barat in early 1999 and the Sampit area of Kalimantan Tengah Province in February 2001. By April 2001, almost 100,000 Madurese, many of whom had resided in Kalimantan for several generations, had been evacuated to Madura and Java. Dayak leaders and government officials conducted reconciliation talks, but the return of the Madurese was slow to occur. [Source: Library of Congress]

Violence in places like West Kalimantan, the Moluccas often has more do with local disputes and the inability of the military to impose order than with "serous separatist threats." In Sumatra a man was beaten and burned alive because he couldn't tell his captors his exact address. Conflict broke out in Maluku Province in 1999 after a seemingly minor clash between a bus driver and a passenger who refused to pay his fare exploded into wide-ranging Muslim–Christian violence in Ambon that quickly expanded throughout the Maluku Islands. More than 5,000 people were killed between 1999 and 2002. Islamic militants in Jakarta called for jihad to support their coreligionists on the islands.

Similar Muslim–Christian violence flared around the Sulawesi Tengah city of Poso during the same period. Hard-line civilian and military sympathizers, who wanted to destabilize the regime of then-President Abdurrahman Wahid, collaborated to organize, train, equip, and arm the Laskar Jihad (Jihad Militia) and arranged the unimpeded transfer of several thousand members of the militia to both Ambon and Poso. This caused a major escalation of the conflict. The government declared a civil emergency, one step short of martial law. In February 2002, leaders of the Christian and Muslim communities in Poso and Maluku Province signed two separate peace agreements aimed at ending three years of sectarian fighting. Both agreements were brokered by Muhammad Yusuf Kalla, who, two years later, was elected vice president of Indonesia. The level of conflict quickly fell, but sporadic violence remained endemic to the entire region. *

See Aceh, West Papua, Madurese, Moluccas, East Timor,

Separatism Issue in Indonesia

In 2007, Rizal Sukma wrote in the Jakarta Post that separatism in Indonesia was far from resolved. Although the government had successfully settled the conflict in Aceh, separatist sentiment was resurfacing in eastern Indonesia. He pointed to two incidents that happened within a single week. In Ambon, Maluku, people entered a National Family Day ceremony, performed the cakalele war dance, and waved flags of the South Maluku Republic (RMS). Around the same time, Papuans waved the Bintang Kejora independence flag during a cultural congress, while Papuan students displayed the same flag at a protest in Yogyakarta. [Source: Rizal Sukma, Jakarta Post, Opinion, July 10 2007. The writer is deputy executive director of the Centre for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS)=]

Sukma argued that separatism has challenged Indonesia since independence in 1945. While armed rebellions had been defeated and Aceh resolved peacefully, the problem persisted in a new form. The real danger, he said, was not military rebellion but non-violent demands for independence. These movements seek international attention and sympathy, which can quickly turn a local issue into a global one—especially if the government responds with force.

He warned that overreaction was exactly what separatist groups wanted. Heavy-handed responses, angry rhetoric, or the use of force would only internationalize the issue and strengthen the movements. Early signs of trouble were already visible, as security agencies began blaming one another for failing to prevent the Ambon incident.

Sukma stressed that while the breach of security at an event attended by the president was serious, separatism itself was a deeper political problem. The government needed to ask why some people in Maluku and Papua continued to feel alienated from the Indonesian state.

The goal, he concluded, should not be to eliminate separatist aspirations entirely—since they will always exist—but to make them unattractive to the wider public. That requires restraint, maturity, and a rejection of repression. Lessons from Aceh showed that violence only creates more violence. Long-term stability, Sukma argued, depends on equality before the law, an end to discrimination, social justice, and convincing citizens that they truly belong to the Indonesian nation.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East / Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993; National Geographic; New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Lonely Planet Guides, Library of Congress, Smithsonian magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Reuters, AP, AFP, Wikipedia, BBC, CNN, and various books and other publications.

Last Updated December 2025