HINDU TEXTS AND EPIC POETRY

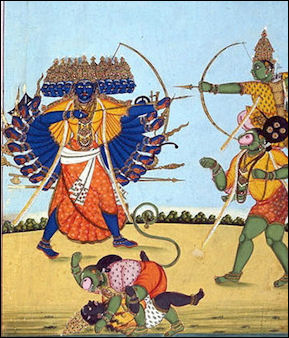

Rama and Hanuman fighting Ravana,

scene from the Ramayana Hinduism have many sacred documents but no single sacred text such as the Bible. "The result," writes historian Daniel Boorstin, is "a wonderfully varied and constantly enriching Hindu jingle-jangle of truths, but no one path to The Truth." Hindu texts are so closely associated with Sanskrit that all translations are regarded as profanation.

There are five primary sacred texts of Hinduism, each associated with a stage of Hinduism’s evolution. They are: 1) the “Verdic Verses” , written in Sanskrit between 1500 to 900 B.C.; 2) the “Upanishads” , written 800 and 600 B.C.; 3) the “Laws of Manu”, written around 250 B.C.; and 4) “Ramayana” and 5) the “Mahabharata”, written sometime between 200 B.C. and A.D. 200 when Hinduism was popularized for the masses.

Hindu cosmology was explained in the Vedas. The Upanishads provided a theoretical basis for this cosmology. The “Brahmanas” , a supplement to the Vedas, offers detailed instructions for rituals and explanations of the duties of priests. It gave form to abstract principals offered up in the earlier texts. Sutras are additional supplements that explain laws and ceremonies.

The beginnings of epic poetry in India may be traced to the dkhydnas, gathas, and nardiamsis, mentioned in the Brahmanas and other later Vedic texts. They were recited by professional rhapsodists at certain ceremonies, and were considered very pleasing to the gods. In course of time these “songs in praise of men” developed into epic poems of considerable length, but of these only two are extant in Sanskrit. The Ramayana and the Mahabharata thus embody a mass of floating legends and bardic lauds recounting the triumphs and reverses, in war and love, of ancient heroes and heroines. [Source: “History of Ancient India” by Rama Shankar Tripathi, Professor of Ancient Indian History and Culture, Benares Hindu University, 1942]

Hindu Texts: Clay Sanskrit Library claysanskritlibrary.org ; Sacred-Texts: Hinduism sacred-texts.com ; Sanskrit Documents Collection: Documents in ITX format of Upanishads, Stotras etc. sanskritdocuments.org ; Ramayana and Mahabharata condensed verse translation by Romesh Chunder Dutt libertyfund.org ; Ramayana as a Monomyth from UC Berkeley web.archive.org ; Ramayana at Gutenberg.org gutenberg.org ; Mahabharata holybooks.com/mahabharata-all-volumes ; Mahabharata Reading Suggestions, J. L. Fitzgerald, Das Professor of Sanskrit, Department of Classics, Brown University brown.edu/Departments/Sanskrit_in_Classics ; Mahabharata Gutenberg.org gutenberg.org ; Bhagavad Gita (Arnold translation) wikisource.org/wiki/The_Bhagavad_Gita ; Bhagavad Gita at Sacred Texts sacred-texts.com ; Bhagavad Gita gutenberg.org gutenberg.org

See Separate Articles HINDU TEXTS: THE VEDAS, BHAGAVAD GITA, RAMAYANA AND MAHABHARTA factsanddetails.com SELECTIONS, PASSAGES AND QUOTES FROM THE VEDAS factsanddetails.com ; UPANISHADS factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“The Rig Veda” by Anonymous and Wendy Doniger (Penguin Classics) Amazon.com ;

“The Holy Vedas” by Pandit Satyakam Amazon.com ;

“The Rig Veda: Complete” (Illustrated) by Anonymous (Author), Ralph T. H. Griffith (Translator) Amazon.com ;

“The Upanishads” by Anonymous and Juan Mascaro (Penguin Classics) Amazon.com ;

“The Mahabharata” by John D. Smith and Anonymous (Penguin Classics) Amazon.com ;

“The Bhagavad Gita” (Easwaran's Classics of Indian Spirituality Book 1) Amazon.com ;

“The Bhagavad Gita” by Anonymous and Laurie L. Patton (Penguin Classics)

Amazon.com ;

“The Ramayana: A Shortened Modern Prose Version of the Indian Epic” by by R. K. Narayan and Pankaj Mishra (Penguin Classics) Amazon.com ;

“The Rāmāya a of Vālmīki: The Complete English Translation (Princeton Library of Asian Translations) Amazon.com ;

“The Illustrated Ramayana: The Timeless Epic of Duty, Love, and Redemption”

by DK and Bibek Debroy Amazon.com

Ramayana and Mahabharta

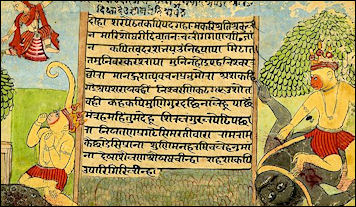

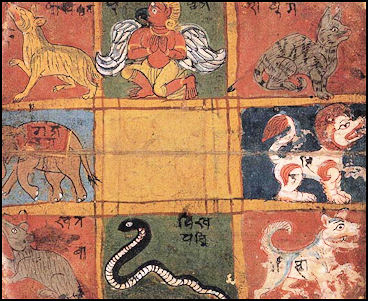

Hanuman slaying demons

on Ramayama manuscript Steven M. Kossak and Edith W. Watts from The Metropolitan Museum of Art wrote: “Indian people have treasured, in particular, two great epics: the Ramayana (2nd century B.C.) and the famous epic poem, the Mahabharata (500–400 B.C.), both of which may be based on actual historical events. The Ramayana has been, and still is, a rich source for art.” [Source: Steven M. Kossak and Edith W. Watts, The Art of South, and Southeast Asia, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York]

The “Ramayana” and the “Mahabharata” are epics like the “Iliad or “ Jason and the Argonauts. Believed to have been written between 200 B.C. and A.D. 200, with some parts probably written earlier and some parts probably written later, they are comprised of myths and stories about romance and war, and are part of a collection of texts, known as “Shmriti” (“That Which has been Remembered”), which are regarded as being supportive of the “shruti”. Amid the adventure of Hindu gods and heroes are found laws and regulation regarding caste, eating, idolatry, sacred places, festivals and superstitions. There are also long didactic passages offering guidance on politics, morality, ethics and religion. Although the “Ramayana” and “Mahabharata” were written millennia ago they remain very much alive today. When a serial drama version of the “Ramayana” was shown on television in the late 1980s and early 1990s the whole country was quiet on Sunday morning as people tuned in. The sale of television sets soared. Those that could not afford new sets gathered around windows to watch episodes. In some places the buses stopped running so the drivers could tune in. The shows was also very popular in Pakistan. One of the most devastating bombing attacks in Karachi took place outside a television shop where people had gathered to watch the series.

Dr. Jukka O. Miettinen of the Theatre Academy of Helsinki wrote: “The great Hindu epics of India, the Mahabharata and the Ramayana, are of enormous importance for the whole culture, not only of India but also of other parts of Asia, particularly in Southeast Asia. They were originally conveyed orally, but they received their written forms in the early centuries AD. Since that time numerous variations have been written in India and other parts of Asia and, for example, the Ramayana has been set in Thailand, Burma, Laos and Cambodia in a Buddhist context, while in Malaysia it is set in an Islamic context. [Source: Dr. Jukka O. Miettinen, Asian Traditional Theater and Dance website, Theatre Academy Helsinki /=/]

“The epics are of crucial importance to the theatrical arts, in two ways. Firstly, they give different kinds of information about theatrical practices from the periods in which they were formulated. Secondly, they provide plots for hundreds of different kinds of theatrical traditions, from simple storytelling to shadow theatre, classical Sanskrit dramas, various forms of dance-dramas, pilgrimage plays, and hundreds of folk traditions.” /=/

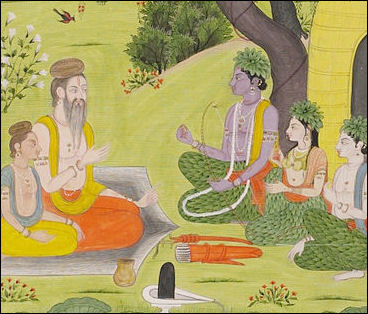

Ramayana

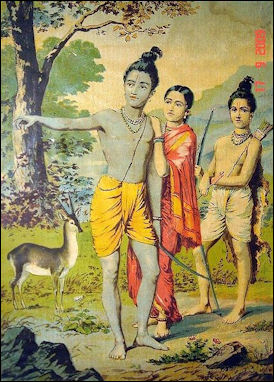

Rama, Sita and LakshmanaRamayana (Sanskrit for "The Romance of Rama" or “The Career of the Rama”) is a great epic poem that is 24,000 verses long. it consists of seven books and tells the story of Rama, or Ramachandra, the King of Ayodhya and the God of Truth, and his adventures. The work is attributed to the poet Valmiki although it was probably written by several authors and embellished over the centuries by others. The Ramayana is a cornerstone of religion and literature not only in India but in other South Asian and Southeast Asian nations as well. It was originally written in Sanskrit but has been translated into numerous other languages. There are many variations. The Ramayana is somewhat reminiscent of the Odyssey in its organization and plot. The stories may be based on a real life king named Rama who helped spread Hindu and Aryan ideas throughout India. Hindu nationalists believe this and based their 1980s attack on mosque in Adoyda’said to have been built on the site of Rama’s birthplace — on this belief.

Simply reading or hearing the Ramayana is said to bring about good things. The last paragraph reads: “He that has no sons shall attain a son by reading even a single verse of Rama’s song. All sin is washed away from those who read or hear it read. He who recites the Ramayana should have rich gifts of cows and gold. Long shall he live who reads the Ramayana, and shall be honored, with sons and grandsons in this world and in Heaven.”

Dr. Jukka O. Miettinen of the Theatre Academy of Helsinki wrote: “The Ramayana, which is probably the world’s most popular epic, tells of the struggle of Prince Rama with the demon-king Ravana. Like Krishna in the Mahabharata, Prince Rama is presented as the avatar or incarnation of the god Vishnu (synopsis of the Ramayana). The Ramayana may have originally been composed collectively, but the legendary author Valmiki is mentioned in connection with it. The epic is less extensive than the Mahabharata, consisting of 12,000 double verses. [Source: Dr. Jukka O. Miettinen, Asian Traditional Theater and Dance website, Theatre Academy Helsinki /=/]

See Separate Articles RAMAYANA: IT'S HISTORY, STORY AND MESSAGES factsanddetails.com ; PASSAGE AND SELECTION FROM THE RAMAYANA: THE INAGURATION OF RAMA AS KING factsanddetails.com

Books: 1) Narayan, R. K., The Ramayana . Harmondsworth: Penguin Classics, 1993; 2) The Adventures of Rama, Washington, D.C.: Freer Gallery of Art, Smithsonian Institution, 1983; 3) Seeger, Elizabeth, The Ramayana . New York: William R. Scott, 1969; 4) Singh, Rani, and Jugnu Singh; 5) The Amazing Adventures of Hanuman, London: BBC Books, 1988.

Characters of the Ramayana

Ravana Rama is the hero and central character of the Ramayana. An avatar of Vishnu, and the eldest of King of Ayodhya’s four sons, he is noble, handsome and skilled and is regarded as the fearless defender of the law of “dharma”. Sita is the heroine and the wife of Rama. She is held up as a paragon of virtue, chastity and devotion. Rama is armed with a bow given to the gods by Shiva and passed down to an ancestor of Sita’s father. Until Rama comes along no one is able to pull the bow which Rama is able to do with ease.

Ravana is the demon king of Lanka and the chief of the “raksasas” (demons). He is a grotesque figure with 10 heads and 20 arms. He carries a variety of weapons in his 20 hands. Each time a head is lopped off in a battle another quickly grows to replace it. It has been said that he symbolizes lust and greed and uses his powers to disrupt the cosmic order and sanctity of women and the family.

The good guys in the Ramayana include 1) King of Ayodhya (stepfather of Rama); 2) Laksmana (half-brother of Rama); and 3) Sugriva (king of the monkeys). 4) The monkey-god general Hanuman (See Hindu Gods) is one of the main characters. He is considered tricky and doesn't hesitate to lie or change his appearance to get what he wants. Often time what he wants most is the approval and adoration of mankind.

The bad guys in the Ramayana include 1) Indrajit (“the invisible warrior” and son of Ravana); 2) Marica (a demon disguised as a golden stag); 3); Viradha (a demon, abductor of Sita); and 4) Vali (the brother and rival of Sugriva). Ravana’s army is comprised of ugly raksasas (“night wanderers”), demons that can fly as fast as the wind and change their appearance.

Early Story of the Ramayana

“Ramayana” is essentially a story of love and banishment. It begins with the gods awakening Vishnu from a deep cosmic sleep and urging him to go to earth to rid the world of Ravana, who through a promise by Brahma can not be defeated by gods and must be defeated by a man. Vishnu descends to earth as the man Rama and woes and wins Sita, daughter of the King of Ayodhya. Rama is given Sita’s hand in marriage by the king because he is able to pull Shiva’s bow.

In the early part of the story, Rama is sent into the forest by King Ayodhya so the son of the king’s second wife can be the successor to the throne. He is accompanied by his brother Laksmana and the uncomplaining Sita. While in the forest the two men live like ascetics, with no complaints from Sita, and have many adventures. In one episode a raksasa kidnaps Sita. Just as it is about to devour her Rama and Laksama rescue her and slay the demon.

Rama in the forest Ravana is entranced by Sita’s beauty and angry at Rama because he rejected Ravana’ sister, who had fallen in live with him. Ravana conspires to abduct Sita with the help of Marica, who disguises himself as a golden deer to lure Rama and Laksmana away from Sita. While Rama and gis brother is distracted Ravana snatches Sita and takes her back to the Golden City of Lanka (present-day Sri Lanka).

Sita is kept captive in Ravana’s castle. The demon threatens Sita with torture unless she marries him. In the meantime Rama and Laksmana go through a series of adventures and battles trying to rescue Sita. They are helped by Hanuman, who discovers where Sita is kept.

When Rama can not get to the island of Lanka he seeks the help of Hanuman, who summons his army of monkeys to form a bridge from India to Lanka. On Lanka, Rama is able enlist the help of Hanuman’s army and the army of the great monkey king Surgriva who Rama helps by slaying his rival with an arrow.

The battle — pitting Rama, and the armies of Hanuman and Surgriva against Ravana and the demons — is the central event of the Ramayana. It begins after Hanuman sets fire to Ravana’s city and continues through a long series of offensives, counterattacks and battles. Ravana’s forces fire arrows that turn into serpents and wind around their victims necks like nooses.

All looks doomed when Indrajit kills Rama and Laksmana and the armies of Sugriva are on the verge of defeat. At this point Hanuman travels off to the Himalayas and brings back some magic herbs that bring Rama and Laksama back to life and revive the armies of Sugriva. In a pair of duels Laksmana manages to kill Indrajit and Rama kills Ravana king with an arrow.

Rama then returns to India and is reunited with Sita after 14 years but suspects her of infidelity. Sita undergoes a trial, offers to throw herself on a funeral pyre to prove her fidelity. The epic ends with Rama banishing innocent Sita to appease his subjects. By the time Rama realizes that she has been faithful it is too late: she has been swallowed up by the earth. The self-sacrificing Sita is regarded as model for the dutiful wife. Some versions of the story have a “happier” ending, with Rama realizing that she has been true when she throws herself in a fire, proving she had in indeed been true.

Ramlila, the Traditional Performance of the Ramayana

In 2005, the Ramayana and Ramlila, the traditional performance of the Ramayana was designated by UNESCO as one of the Masterpieces of the Oral and Intangible Heritage of Humanity. According to UNESCO: “Ramlila, literally “Rama’s play”, is a performance of then Ramayana epic in a series of scenes that include song, narration, recital and dialogue. It is performed across northern India during the festival of Dussehra, held each year according to the ritual calendar in autumn. The most representative Ramlilas are those of Ayodhya, Ramnagar and Benares, Vrindavan, Almora, Sattna and Madhubani. [Source: UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage]

“This staging of the Ramayana is based on the Ramacharitmanas, one of the most popular storytelling forms in the north of the country. This sacred text devoted to the glory of Rama, the hero of the Ramayana, was composed by Tulsidas in the sixteenth century in a form of Hindi in order to make the Sanskrit epic available to all. The majority of the Ramlilas recount episodes from the Ramacharitmanas through a series of performances lasting ten to twelve days, but some, such as Ramnagar’s, may last an entire month. Festivals are organized in hundreds of settlements, towns and villages during the Dussehra festival season celebrating Rama’s return from exile.

“Ramlila recalls the battle between Rama and Ravana and consists of a series of dialogues between gods, sages and the faithful. Ramlila’s dramatic force stems from the succession of icons representing the climax of each scene. The audience is invited to sing and take part in the narration. The Ramlila brings the whole population together, without distinction of caste, religion or age. All the villagers participate spontaneously, playing roles or taking part in a variety of related activities, such as mask- and costume making, and preparing make-up, effigies and lights. However, the development of mass media, particularly television soap operas, is leading to a reduction in the audience of the Ramlila plays, which are therefore losing their principal role of bringing people and communities together.”

See Theater

Mahabharta

Shoorsena-Saini, Mahabharta verses The “Mahabharata” (Sanskrit for the “Great Bharata War”) is recognized by the Guinness Book of Worlds Records as the world's longest literary work in verse. Written mostly at the beginning of the Christian era when Hinduism was popularized for the masses, it is composed of 100,000 couplets and is divided into 18 books. It is 15 times longer than the Bible and eight times longer than the Iliad and Odyssey combined.

The “Mahabharta” is filled with stories of love, honor, betrayal, good deeds, evil acts, victory and defeat. Hundreds of television program have been made from its episodes. It has been said that everything that exists in life can be found in the “Mahabharta” , and if it isn’t in the epic then it can’t be found anywhere. The conclusions of the episodes are much more morally ambiguous than in the Ramayana. There are great heros and battlefield but victories often evoke more of a sense of tragedy than celebration.

The “Mahabharta” is somewhat reminiscent of the Iliad , with much of the action and plot related to battles and warfare. The great war featured in the Mahabharata may be based on a real battle that took place sometime around the 13th or 14th century B.C. The verses were originally written in Sanskrit. Some of the richness of the poetry and resonating sounds of the original have been lost in translation.

Dr. Jukka O. Miettinen of the Theatre Academy of Helsinki wrote: “The Mahabharata could be regarded as the national epic of India. It is the world’s largest epic poem, consisting of some 100,000 double verses. Like other great epics, the Mahabharata, written in Sanskrit, is a collective work, and its author is unknown. It has been generally assumed that the poem relates events that happened during a period of tribal warfare in Northern India in approximately the ninth century B.C. The epic contains elements of the ancient, holy Veda texts, but its final form evolved over the centuries as it was sung by local “bards” or “troubadours”, who added new details and emphases to it. [Source: Dr. Jukka O. Miettinen, Asian Traditional Theater and Dance website, Theatre Academy Helsinki /=/]

“The ethic norms of the priestly Brahman class were added to the story, and the Mahabharata gradually became a cornerstone of Hindu thinking. In its richness and diversity of levels, the Mahabharata is not only an ageless description of ancient clan disputes and bloody warfare, but also an image of an ultimately Indian way of conceiving the world and man’s duty in it. The Mahabharata is an immense work with numerous subplots, and hundreds of characters and episodes, from which independent literary works have arisen.” /=/

See Separate Article MAHABHARATA AND BHAGAVAD GITA factsanddetails.com

Story in the Mahabharta

Manuscript from Nepal

in Newari and Sanskrit The “Mahabharta” describes a conflict between the Pandavas and Kauravas, two related clans in the Kuri tribe in the Delhi area, in Vedic times. The story begins when the oldest of the five Pandava brothers, a king, wages his entire kingdom, including his wife, on a dice game and loses. His queen is forced to come into the gambling hall and strip before the winners. After an appeal to the gods, a sari magically appears every time she takes her clothes off until finally she is surrounded by a mountain of saris, shielding her naked body from the leering eyes in the hall.

A deal is struck that allows the Pandavas to reclaim their kingdom after spending 14 years in the forest. When that the time is up the blind King Dhritarashtra, head of the Kauravas, refuses to hand over the throne and Pandava prepare for battle. King Dhritarashtra is assisted by his counselor Sanjaya, who has special powers which enable him to see events in far off places. The battle is regarded as metaphor of the struggles that go on within an individual.

Krishna is the charioteer of Prince Arjuna, the third Pandava son. He helps the prince and teaches him about the knowledge of truth and devotion to the Higher Self. Arjuna has a magical bow named Gandiva that can shoot 30,000 arrows at one time. Krishna also gives Arjuna a "third eye" that allows the archer to see the deities in "universal form" — "all wonderful, resplendent, boundless...If the radiance of a thousand suns were to burst forth at once in the sky, that would be like the splendor of the Mighty One.”

Bhagavad Gita

Khom Sanskrit The “Bhagavad Gita” ("Song of God") is an epic poem consisting of 701 Sanskrit couplets. Part of the “Mahabharata”, it blends theology and political science with a dramatic story of dynastic struggle. According to legend it was written by the sage Vyasa. It probably existed independently of the “Mahabharata” and was added and revised to its present form around the A.D. 2nd century. Today, it is the most widely read Hindu text.

The “Bhagavad Gita” is essentially a devotional poem set among the battles of the “Mahabharata” . It outlines rituals accessible to everyone. This contrasts with the rituals described in old Vedic texts, which involved sacrifices and elaborate rites that were only open to upper castes. Many customs and fetishes have evolved around the “Bhagavad Gita” . Some people wear a miniature copy of it around their neck for luck and to ward off evil.

The “Bhagavad Gita” begins at the battlefield of Kurukshetra, a popular pilgrimage place today. Arjuna is brooding over the upcoming clash because he has friends, relatives and teachers on the other side. Krishna advises him to pour himself into the battle and not worry about the consequences, telling the warrior that is the only way he can find knowledge, freedom and peace.

Much of the text is made of dialogues between Krishna and Arjuna with Krishna encouraging Arjuna to fight and overcome his reluctance not to fight. Krishna tells Arjuna that he must fight because he is a warrior by caste and it is his duty to fight, saying: “For there is more joy in doing one’s duty badly that in doing another’s well. It is a joy to die doing one’s duty, but doing another man’s duty brings dread.”

See Separate Article MAHABHARATA AND BHAGAVAD GITA factsanddetails.com

Epics on Kings, Armies and Government in Ancient India

The two Epics have not only many common phrases and fables but the conditions depicted in them are very much alike. We shall accordingly draw on both together for a picture of the life of the princes and the people. It must, however, be remembered that all the data do not relate to any particular period, as the Epics are a gradual growth, and were compiled and enlarged centuries after the events described. [Source: “History of Ancient India” by Rama Shankar Tripathi, Professor of Ancient Indian History and Culture, Benares Hindu University, 1942]

The epic king was not an absolute despot Satisfying his personal caprice only. He was amenable to the will of his brothers, councillors and the populace. He had also to recognise and respect the laws of different groups — Kailas (families), Jatis (castes), Srenis (guilds), and Piigas (communities). A wicked king was deposed or killed “like a mad dog.” Even the immediate heir, if bodily defective, was not called to the throne. The king was installed and crowned with due ceremonies, and he was the leader of his people both “at home and in the field.” He was expected to undertake expeditions with the advice of the ministers and the blessings of the priest, but in practice the king probably decided the matter himself in "collaboration with his allies. The Sabhd had now become a mere body for consultation on military matters. The king lived amid pomp and splendour, and dancing-girls ana women of easy virtue formed a part of his retinue. His chief recreations were music, gambling, hunting, animal fights, and wrestling contests. He meted out justice in the hall adjoining the palace. In old age he usually abdicated or retired in favour of his eldest son.

The capital was well protected with a surrounding wall, gates, towers, and moats, and supplied with the necessary amenities of life. There were music-halls, pleasure-gardens, well-laid out squares, beautiful buildings for the king and grandees of the court, and attractive booths for traders. The thoroughfares were lighted at night with lamps, and the dust-nuisance was allayed by watering them regularly.

The king administered the realm with the help of a Mantriparisad (ministry), which, according to the Mahdbhdrata ) consisted of four Hindus, eight Ksatriyas, twenty-one Vaisyas, three Sudras, and one of the Suta caste. The Prime-minister and other councillors were men of the highest integrity, sagacity, and character. Besides, the king was assisted in the discharge of his duties by subordinate rulers (Sd mantas), the Ynvardja (Crown-prince), the aristocracy, and such high officers as Purohita (Priest), Camupati (Commander-in-chief), Dvarapala (Chamberlain), Pradesta (Chief Justice), Dharmadhyaksa (Superintendent of Justice), Dandapdla (Presiding Judge of the Criminal Courts, or Chief Police Officer ?), Nagaradhyaksa (City -Prefect), Kdryanirmanakrit (Superintendent of Works), Kdrdgdradhikdri (Superintendent of Prisons), Durgapala (Warden of forts), etc. [Source: “History of Ancient India” by Rama Shankar Tripathi, Professor of Ancient Indian History and Culture, Benares Hindu University, 1942]

Ravana losing his heads

The village or grama, which was the lowest unit of administration, enjoyed considerable local autonomy under its headman (Gram ant). Next, in the ascending scale were officers of ten (Datagrams), twenty (VimJatipa), a hundred (Satagrami), and a thousand villages (. Adhipati). These officers collected revenue, detected crime, and maintained order within their jurisdictions, each being responsible to the next higher authority, and all eventually to the king.

The king’s army consisted of the Aryan nobles and commoners, who served as archers, slingers, rockthrowers, cavalrymen, chariot-drivers, elephant-riders, etc. The suggestion that fire-arms i.e., cannon and gunpowder were also used will hardly bear criticism. AH that one may believe is that perhaps there were some “magically blazing” weapons like Cakras and arrows. It was deemed glorious for the warrior to die fighting. The Ksatriya fought for renown or for his chieftain. The king pensioned the widows of the fallen. Those captured in battle became the victor’s slaves for a year at least. Sometimes, however, they were restored to freedom on certain conditions. Incidentally, it may be interesting to note that grass-eating was regarded as a sign of submission. [Source: “History of Ancient India” by Rama Shankar Tripathi, Professor of Ancient Indian History and Culture, Benares Hindu University, 1942]

Epics on People and Life in Ancient India

Caste was already a firmly-rooted institution. The nobles and the Hindus had the upper hand in society, whereas the un-Aryan “Sudras” were the under-dogs, and the slaves, “born to servitude,” had no rights and possessions. The position of women had deteriorated as compared with what it was in the Vedic age. The custom of Safi is spoken of, and polygamy was practised. Going out veiled, sometimes referred to, was perhaps a court-custom. We also hear of Svajamvaras, i.e., self-selection of the bridegroom. [Source: “History of Ancient India” by Rama Shankar Tripathi, Professor of Ancient Indian History and Culture, Benares Hindu University, 1942]

The bulk of the population lived in villages around forts (durga), perhaps of mud, tending cattle and practising agriculture. In times of danger, such as war and cattle-lifting raids, they took shelter inside these rude defences. The villagers were autonomous in ordinary affairs, but the king as the overlord administered justice and exacted taxes, which varied according to need and were perhaps paid mostly in kind. Merchants and others dwelt in towns. The former brought goods from afar, and paid customs duties. Townsfolk probably paid fines and taxes in money. The use of false-weights, sometimes alluded to, must have necessitated a careful supervision of the market-place by the state. The guilds of merchants and artisans wielded great influence, and, next to the priests, their heads (mahajana) were the objects of royal attention and solicitude.

The people were into to eating meat and drinking intoxicating liquors, although vegetarianism was gradually gaining ground on account of the doctrine of Abimsa, stressed by the best minds of ancient times.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “Encyclopedia of the World’s Religions” edited by R.C. Zaehner (Barnes & Noble Books, 1959); “Encyclopedia of the World Cultures: Volu” edited by David Levinson (G.K. Hall & Company, New York, 1994); “The Creators” by Daniel Boorstin; “A Guide to Angkor: an Introduction to the Temples” by Dawn Rooney (Asia Book) for Information on temples and architecture. National Geographic, the New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Times of London, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated September 2020