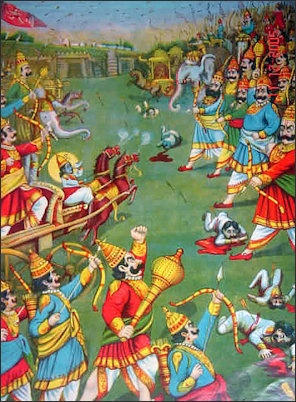

MAHABHARATA

Battle of Kurukshetra

The Mahabharata (pronounced approximately as Ma-haa-BHAAR-a-ta) is an ancient religious epic of India and arguably the most famous Indian text. Attributed to the poet Vyasa, the epic is divided into 18 sections, containing over 220,000 lines. The most famous section is the Bhagavad Gita. It is the sixth book of the Mahabharata and contains the central text of Hinduism. The Mahabharata is somewhat reminiscent of the Iliad while the other great Indian literary text, The Ramayana, is somewhat reminiscent of the Odyssey. The great war featured in the Mahabharata is thought to have been fought around the 13th or 14th century B.C.

The Mahabharata ("The Great Tale of the Bharatas") may well be the world's second largest book (after the Gesar Epic of Tibet). Unlike the Vedas, which are considered "sruti" or divine revelation, the epics are considered smrti ("that which is remembered") or of human origin. The Mahabharata is said to have been written by Vyasa. Who he was and when he lived is not known.

The Mahabharata was , probably compiled before A.D. 400). It mostly describes the great civil war between the Pandavas (the good) and the Kauravas (the bad) — two factions of the same clan. It is believed that the war was created by Krishna. Perhaps the flashiest and craftiest avatar of Vishnu, Krishna, as a part of his lila (sport or act), is believed motivated to restore justice — the good over the bad. [Source: Andrea Matles Savada, Library of Congress, 1991]

James L. Fitzgerald, a professor of Sanskrit at Brown University, wrote: “ simply, the Mahabharata is a powerful and amazing text that inspires awe and wonder. It presents sweeping visions of the cosmos and humanity and intriguing and frightening glimpses of divinity in an ancient narrative that is accessible, interesting, and compelling for anyone willing to learn the basic themes of India's culture. The Mahabharata definitely is one of those creations of human language and spirit that has traveled far beyond the place of its original creation and will eventually take its rightful place on the highest shelf of world literature beside Homer's epics, the Greek tragedies, the Bible, Shakespeare, and similarly transcendent works.” [Source: James L. Fitzgerald, Das Professor of Sanskrit, Department of Classics, Brown University, July 30, 2009 */]

Hindu Texts: Clay Sanskrit Library claysanskritlibrary.org ; Sacred-Texts: Hinduism sacred-texts.com ; Sanskrit Documents Collection: Documents in ITX format of Upanishads, Stotras etc. sanskritdocuments.org ; Ramayana and Mahabharata condensed verse translation by Romesh Chunder Dutt libertyfund.org ; Ramayana as a Monomyth from UC Berkeley web.archive.org ; Ramayana at Gutenberg.org gutenberg.org ; Mahabharata holybooks.com/mahabharata-all-volumes ; Mahabharata Reading Suggestions, J. L. Fitzgerald, Das Professor of Sanskrit, Department of Classics, Brown University brown.edu/Departments/Sanskrit_in_Classics ; Mahabharata Gutenberg.org gutenberg.org ; Bhagavad Gita (Arnold translation) wikisource.org/wiki/The_Bhagavad_Gita ; Bhagavad Gita at Sacred Texts sacred-texts.com ; Bhagavad Gita gutenberg.org gutenberg.org

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“The Mahabharata” by John D. Smith and Anonymous (Penguin Classics) Amazon.com ;

“The Bhagavad Gita” (Easwaran's Classics of Indian Spirituality Book 1) Amazon.com ;

“The Bhagavad Gita” (Penguin Classics) by Anonymous and Laurie L. Patton

Amazon.com ;

“The Rig Veda” by Anonymous and Wendy Doniger (Penguin Classics) Amazon.com ;

“The Holy Vedas” by Pandit Satyakam Amazon.com ;

“The Rig Veda: Complete” (Illustrated) by Anonymous (Author), Ralph T. H. Griffith (Translator) Amazon.com ;

“The Upanishads” by Anonymous and Juan Mascaro (Penguin Classics) Amazon.com ;

“The Ramayana: A Shortened Modern Prose Version of the Indian Epic” by by R. K. Narayan and Pankaj Mishra (Penguin Classics) Amazon.com ;

“The Rāmāya a of Vālmīki: The Complete English Translation (Princeton Library of Asian Translations) Amazon.com ;

“The Illustrated Ramayana: The Timeless Epic of Duty, Love, and Redemption”

by DK and Bibek Debroy Amazon.com

History of the Mahabharata

The Mahabharata story first began in the oral tradition during the first millennium B.C. and was composed in Sanskrit over centuries, beginning perhaps as early as 800 or 900 B.C., and reaching its final written form around the fourth century B.C. James L. Fitzgerald, a professor at Brown University, wrote: “ The Mahabharata has existed in various forms for well over two thousand years: First, starting in the middle of the first millennium B.C., it existed in the form of popular stories of Gods, kings, and seers retained, retold, and improved by priests living in shrines, ascetics living in retreats or wandering about, and by traveling bards, minstrels, dance-troupes, etc. [Source: James L. Fitzgerald, Das Professor of Sanskrit, Department of Classics, Brown University, July 30, 2009 */]

Ganesha and Vyasa writing the Mahabharata

“Later, after about 350 CE, it came to be a unified, sacred text of 100,000 stanzas written in Sanskrit, distributed throughout India by kings and wealthy patrons, and declaimed from temples. Even after it became a famous Sanskrit writing it continued to exist in various performance media in many different local genres of dance and theater throughout India and then Southeast Asia. Finally, it came to exist, in numerous literary and popular transformations in many of the non-Sanskrit vernacular languages of India and Southeast Asia, which (with the exception of Tamil, a language that had developed a classical literature in the first millennium B.C.) began developing recorded literatures shortly after 1000 CE. */

“The Mahabharata was one of the two most important factors that created the "Hindu" culture of India (the other was the other all-India epic, the Ramayaa... and the Mahabharata and Ramayaa still exert tremendous cultural influence throughout India and Southeast Asia. But the historical importance of the Mahabharata is not the main reason to read the Mahabharata. Quite simply, the Mahabharata is a powerful and amazing text that inspires awe and wonder.” */

The Mahdbharata is divided into 18 books (parvans) of unequal size with the Harivamda as a supplement. According to orthodox tradition, Dvaipayana Vyasa was the author of this stupendous work, but the essential lack of uniformity in its language, style, and contents clearly indicates that it is not the production of one brain or of one period. It is a gradual growth from an epic kernel, which was in course of time thoroughly remodelled, extended, and enriched by Hindus with an enormous amount of mythological, philosophical, religious, and didactic matter. The A.svalayana Grihyasiitra furnishes the oldest evidence for the existence of the Mahabharata in some form, and a land-grant of about 500 A.D. where it is definitely called “a collection of a hundred thousand verses,” shows that by this date, or some time — say a century — earlier, it already existed in its present shape. Thus the beginnings, growth, revision, and interpolations of this tremendous compilation are to be ascribed to this long interval between the fifth century B.C. and 400 A.D. roughly. [Source: “History of Ancient India” by Rama Shankar Tripathi, Professor of Ancient Indian History and Culture, Benares Hindu University, 1942]

In the main the story of the Mahabharata is based on historical truth. Hastinapur and Indraprastha were doubtless real cities, and, despite their utter destruction by the ravages of time and the elements, their names still survive. The former is now represented by a hamlet of the same name on the Ganges in the Meerut district, and the latter is recognised in the small village of Indarpat on the Jumna, near modern Delhi. The traditional date, 3102 B.C., of the famous war between the ruiers of the two places will hardly stand the test of criticism, but it has with some plausibility been placed about 1000 B.C.

For the Satapatha Brahmana is familiar with the heroes of the epic, and it mentions Janamejaya as almost a recent personage. It is also known that the Kurus were a great people during the later Vedic period, although the Pandus do not at all figure either in the Brahmanas or in the Sutras. They first emerge into view with the later Buddhist literature as a mountain tribe. Does this show, as has sometimes been conjectured, that they were foreign immigrants, unrelated to the Kurus ? At any rate, the theory is supported to some extent by their rude, uncourtly manners; practice of polyandry; and the name “Pandu,” meaning “pale,” which may perhaps indicate their Mongolian affinities. If the suggestion has any substance, the present text of the Mahdbharata gives an altogether garbled version of the actual origins and relations of the chief combatants. Similarly, it is difficult to accept its testimony regarding their allies. For instance, we learn that the Kuru hosts included the rulers of Pragjyotisa (Assam), Avanti and Daksinapatha, the CInas, Kiratas, Kambojas, Yavanas, Sakas, Madras, Kaikeyas, Sindhus, Sauviras etc. Apart from the fact that they were not all contemporaneous, it is doubtful whether these distant powers "were interested in what was perhaps a local conflagration in Madhyadesa. And surely they could not be called to arms as feudatories, for the nearness of the Kaurava and Pandava capitals itself shows that they did not hold an extensive sway. In short, there are undoubted deviations from historical accuracy in the Mahdbharata, but the central theme is authentic, and its characters, whose exploits were first popularised by story-tellers and minstrels, are by no means imaginary.

Main Characters of the Mahabharata

The Mahabharta describes a conflict between the Pandavas (Paavas) and Kauravas (Dhartararas), two related clans in the Kuri tribe in the Delhi area, in Vedic times. Professor Fitzgerald wrote: “The innermost narrative kernel of the Mahabharata tells the story of two sets of paternal first cousins—the five sons of the deceased king Pau [pronounced PAAN-doo] (the five Paavas [said as PAAN-da-va-s]) and the one hundred sons of blind King Dhtarara [Dhri-ta-RAASH-tra] (the 100 hundred Dhartararas [Dhaar-ta-RAASH-tras])—who became bitter rivals, and opposed each other in war for possession of the ancestral Bharata [BHAR-a-ta] kingdom with its capital in the "City of the Elephant," Hastinapura [HAAS-ti-na-pu-ra], on the Gaga river in north central India. What is dramatically interesting within this simple opposition is the large number of individual agendas the many characters pursue, and the numerous personal conflicts, ethical puzzles, subplots, and plot twists that give the story a strikingly powerful development. [Source: James L. Fitzgerald, Das Professor of Sanskrit, Department of Classics, Brown University, July 30, 2009 */]

Arjuna embracing ascetism for a year

“The five sons of Pau were actually fathered by five Gods (sex was mortally dangerous for Pau, because of a curse) and these heroes were assisted throughout the story by various Gods, seers, and brahmins, including the seer Ka Dvaipayana Vyasa [VYAA-sa] (who later became the author of the epic poem telling the whole of this story), who was also their actual grandfather (he had engendered Pau and the blind Dhtarara upon their nominal father's widows in order to preserve the lineage). The one hundred Dhartararas, on the other hand, had a grotesque, demonic birth, and are said more than once in the text to be human incarnations of the demons who are the perpetual enemies of the Gods.*/

“The most dramatic figure of the entire Mahabharata, however, is Ka, son of Vasudeva of the tribe of Andhaka Vis, located in the city of Dvaraka in the far west, near the ocean. His name is, thus Ka Vasudeva [Vaa-su-DAY-va]. But he also a human instantiation of the supreme God Vasudeva-Narayaa-Viu descended to earth in human form to rescue Law, Good Deeds, Right, Virtue and Justice (all of these words refer to different facets of "dharma," the “firm-holding” between the ethical quality of an action and the quality of its future fruits for the doer). Ka Vasudeva was also a cousin to both Bharata phratries, but he was a friend and advisor to the Paavas, became the brother-in-law of Arjuna [AR-ju-na] Paava, and served as Arjuna's mentor and charioteer in the great war. Ka Vasudeva is portrayed several times as eager to see the purgative war occur, and in many ways the Paavas were his human instruments for fulfilling that end.” */

Tribe in the Mahabharata

In order to understand the allusions made in the Bhagavad-Gita, it is important to have some knowledge of the tribe and people, which lies at the heart of the story. J. Cockburn Thomson, a 19th century translator of the Bhagavad-Gita, wrote: The Mahabharata is about "two branches of one tribe, the descendants of Kuru, for the sovereignty of Hastinapura, commonly supposed to be the same as the modern Delhi. The elder branch is called by the general name of the whole tribe, Kurus; the younger goes by the patronymic from Pandu, the father of its five principal leaders. Of the name Kuru we know but little, but that little is sufficient to prove that it is one of great importance. We have no means of deriving it from any Sanskrit root, nor has it, like too many of the old Indian names, the appearance of being explanatory of the peculiarities of the person or persons whom it designates. It is, therefore, in all probability, a name of considerable antiquity, brought by the Aryan race from their first seat in Central Asia. Its use in Sanskrit is fourfold. It is the name of the northern quarter, or Dwipa, of the world, and is described as lying between the most northern range of snowy mountains and the polar sea. It is, further, the name of the most northern of the nine Varshas of the known world. Among the long genealogies of the tribe itself, it is found as the name of an ancient king, to whom the foundation of the tribe is attributed. Lastly, it designates an Aryan tribe of sufficient importance to disturb the whole of northern India with its factions, and to make its battles the theme of the longest epic of olden time. [Source: J. Cockburn Thomson]

Drpadi and Her Attendants

"Viewing these facts together, we should be inclined to draw the conclusion that the name was originally that of a race inhabiting Central Asia beyond the Himalaya, who emigrated with other races into the northwest of the Peninsula, and with them formed the great people who styled themselves unitedly Arya, or the Noble, to distinguish them from the aborigines whom they subdued, and on whose territories they eventually settled. . . .

"At the time when the plot of the Mahabharata was enacted, this tribe was situated in the plain of the Doab, and their particular region, lying between the junma and Sursooty rivers, was called Kurukshetra, or the plain of the Kurus. The capital of this country was Hastinapura, and here reigned, at a period of which we cannot give the exact date, a king named Vichitravirya. He was the son of Santanu and Satyavati; and Bhishma and Krishna Dwaipayana, the Vyasa, were his half-brothers; the former being his father's, the latter his mother's son. He married two sisters — Amba and Ambalika — but dying shortly after his marriage . . . he left no progeny; and his half-brother,the Vyasa.

The Vyasa, instigated by divine command, married his widows and begot two sons, Dhritarashtra and Pandu. The former had one hundred sons, the eldest of whom was Duryodhana. The latter married firstly Pritha, or Kunti, the daughter of Sura, and secondly Madri. The children of these wives were the five Pandava princes; but as their mortal father had been cursed by a deer while hunting to be childless all his life, these children were mystically begotten by different deities. Thus Yudhishthira, Bhima, and Arjuna, were the sons of Pritha by Dharnma, Vayu, and Indra, respectively. Nakula was the son of Madri by Nasatya the elder, and Sahadeva, by Dasra the younger of the twin Asvinau, the physicians of the gods. This story would seem to be a fiction, invented to give a divine origin to the five heroes of the poem: but, however this may be, Duryodhana and his brothers are the leaders of the Kuru, or elder branch of the tribe; and the five Pandava princes those of the Pandava or younger branch.

"Dhritarashtra was blind, but although thus incapacitated for governing, he retained the throne, while his son Duryodhana really directed the affairs of the State. . . . he prevailed on his father to banish his cousins, the Pandava princes, from the country. After long wanderings and varied hardships, these princes collected their friends around them, formed by the help of many neighboring kings a vast army, and prepared to attack their unjust oppressor, who had, in like manner, assembled his forces.

Story of the Mahabharata

Pandavas in Drupada's court

Set in the kingdom of Kurukshetra on India's northern plains, the epic narrates a succession struggle among members of the Bharata ruling family that results in a ruinous civil war. The Pandava brothers are pitted against their rival cousins, the Kauravas, who divest the eldest Pandava brother of his kingdom and his wife in a fixed gambling match. The brothers are forced into exile for 13 years during which time they prepare for war with their cousins. The Pandavas prevail in an 18-day battle that causes great loss of life on both sides. [Source: PBS, The Story of India, pbs.org/thestoryofindia]

The framework of the epic deals with the great conflict between the Kauravas, the hundred sons of Dhritarastra, and the Panda vas, the five sons of Pandu. It was the culmination of their long-standing rivalry, which began thus: After the death of Vicitra-Virya, the Kuru ruler, his younger son Pandu succeeded him, as the elder, Dhritarastra, was born blind. But owing to Pandu’s premature death, Dhritarastra himself had to assume the reins of government within a short time. Being fond of his nephew, Yudhisthira, a man of rare virtue, he then nominated him heir-apparent. This aroused the jealousy of his eldest son, Duryodhana, who by his machinations compelled the Pandus to escape from the capital. During their wanderings they went to Pancala, where Arjuna won in a svayamvara the king’s daughter, DraupadI, tor himself and his brothers. This alliance proved a turning-point in their fortunes, for with a view to conciliating them Dhritarastra divided his kingdom, giving Hastinapur to his sons, and to his nephews a region of which Indraprastha became the capital. Here, too, the Pandavas were not allowed to reign in peace. Duryodhana lured Yudhisthira to play with him a game of dice, in which the latter lost everything — kingdom, wife, honour — and had to go in exile for twelve years. On the expiry of the period, he tried to get back the lost kingdom, but Duryodhana scornfully rejected Yudhisthira’s terms. This led to a trial of strength. Hostilities lasted eighteen days on the famous battlefield of Kuruksetra, and there was indescribable suffering and slaughter. Ultimately victory rested with Yudhisthira, who ruled gloriously for a brief period, and then retired to the Himalayas with his brothers, giving the care of the crown to the distinguished Pariksit. [Source: “History of Ancient India” by Rama Shankar Tripathi, Professor of Ancient Indian History and Culture, Benares Hindu University, 1942]

Professor James L. Fitzgerald wrote: “The Dhartarara party behaved viciously and brutally toward the Paavas in many ways, from the time of their early youth onward. Their malice displayed itself most dramatically when they took advantage of the eldest Paava, Yudhihira [Yu-DHISH-thir-a] (who had by now become the universal ruler of the land) in a game of dice: The Dhartararas 'won' all his brothers, himself, and even the Paavas' common wife Draupadi [DRAO-pa-dee] (who was an incarnation of the richness and productivity of the Goddess "Earthly-and-Royal Splendor," Sri [Shree]); they humiliated all the Paavas and physically abused Draupadi; they drove the Paava party into the wilderness for twelve years, and the twelve years had to be followed by the Paavas' living somewhere in society, in disguise, without being discovered, for one more year. [Source: James L. Fitzgerald, Das Professor of Sanskrit, Department of Classics, Brown University, July 30, 2009 */]

“The Paavas fulfilled their part of that bargain, but the villainous leader of the Dhartarara party, Duryodhana [Dur-YODH-ana], was unwilling to restore the Paavas to their half of the kingdom when the thirteen years had expired. Both sides then called upon their many allies and two large armies arrayed themselves on 'Kuru's Field' (Kuru was one of the eponymous ancestors of the clan), eleven divisions in the army of Duryodhana against seven divisions for Yudhihira. Much of the action in the Mahabharata is accompanied by discussion and debate among various interested parties, and the most famous sermon of all time, Ka Vasudeva's ethical lecture accompanied by a demonstration of his divinity to his charge Arjuna (the justly famous Bhagavad Gita [BHU-gu-vud GEE-taa]) occurred in the Mahabharata just prior to the commencement of the hostilities of the war. Several of the important ethical and theological themes of the Mahabharata are tied together in this sermon, and this "Song of the Blessed One" has exerted much the same sort of powerful and far-reaching influence in Indian Civilization that the New Testament has in Christendom.” */

Great War in the Mahabharata

J. Cockburn Thomson wrote: The theme of the whole work is a certain war which was carried on between two branches of one tribe...This war between the Kurus and Pandavas occupies about twenty thousand slokas, or a quarter of the whole work...The hostile armies meet on the plain of the Kurus. Bhishma, the half-brother of Vichitravirya, being the oldest warrior among them, has the command of the Kuru faction; Bhima, the second son of Pandu, noted for his strength and prowess, is the general of the other party [Arjuna's]. The scene of our poem now opens, and remains throughout the same — the field of battle. [Source: J. Cockburn Thomson]

“In order to introduce to the reader the names of the principal chieftains in each army, Duryodhana is made to approach Drona, his military preceptor, and name them one by one. The challenge is then suddenly given by Bhishma, the Kuru general, by blowing his conch; and he is seconded by all his followers. It is returned by Arjuna, who is in the same chariot with the god Krishna, who, in compassion for the persecution he suffered, had become his intimate friend, and was now acting the part of a charioteer to him. He is followed by all the generals of the Pandavas.

“The fight then begins with a volley of arrows from both sides; but when Arjuna perceives it, he begs Krishna to draw up the chariot in the space between the two armies, while he examines the lines of the enemy. The god does so, and points out in those lines the numerous relatives of his friend. Arjuna is horror-struck at the idea of committing fratricide by slaying his near relations, and throws down his bow and arrow, declaring that he would rather be killed without defending himself, than fight against them. Krishna replies with the arguments which form the didactic and philosophical doctrines of the work, and endeavors to persuade him that he is mistaken in forming such a resolution. Arjuna is eventually overruled. The fight goes on, and the Pandavas defeat their opponents."

Pandavas opposing the Kauravas in a semi-circular position

On the allusion drawn from the battle,William Q. Judge, translator of the Bhagavad-Gita, wrote in 1890: “The hostile armies who meet on the plain of the Kurus are two collections of the human faculties and powers, those on one side tending to drag us down, those on the other aspiring towards spiritual illumination. The battle refers not only to the great warfare that mankind as a whole carries on, but also to the struggle which is inevitable as soon as any one unit in the human family resolves to allow his higher nature to govern him in his life. Hence, bearing in mind the suggestion made by Subba Row, we see that Arjuna, called Nara, represents not only Man as a race, but also any individual who resolves upon the task of developing his better nature. What is described as happening in the poem to him will come to every such individual.Opposition from friends and from all the habits he has acquired, and also that which naturally arises from hereditary tendencies, will confront him, and then it will depend upon how he listens to Krishna, who is the Logos shining within and speaking within, whether he will succeed or fail.”

Impact of the Great War in the Mahabharata

Professor James L. Fitzgerald wrote: “The Paavas won the eighteen day battle, but it was a victory that deeply troubled all except those who were able to understand things on the divine level (chiefly Ka, Vyasa, and Bhima [BHEESH-ma], the Bharata patriarch who was emblematic of the virtues of the era now passing away). The Paavas' five sons by Draupadi, as well as Bhimasena [BHEE-ma-SAY-na] Paava's and Arjuna Paava's two sons by two other mothers (respectively, the young warriors Ghaotkaca [Ghat-OT-ka-cha] and Abhimanyu [Uh-bhi-MUN-you ("mun" rhymes with "nun")]), were all tragic victims in the war. Worse perhaps, the Paava victory was won by the Paavas slaying, in succession, four men who were quasi-fathers to them: Bhima, their teacher Droa [DROE-na], Kara [KAR-na] (who was, though none of the Paavas knew it, the first born, pre-marital, son of their mother), and their maternal uncle Salya (all four of these men were, in succession, 'supreme commander' of Duryodhana's army during the war). Equally troubling was the fact that the killing of the first three of these 'fathers,' and of some other enemy warriors as well, was accomplished only through 'crooked stratagems' (jihmopayas), most of which were suggested by Ka Vasudeva as absolutely required by the circumstances. [Source: James L. Fitzgerald, Das Professor of Sanskrit, Department of Classics, Brown University, July 30, 2009 */]

“The ethical gaps were not resolved to anyone's satisfaction on the surface of the narrative and the aftermath of the war was dominated by a sense of horror and malaise. Yudhihira alone was terribly troubled, but his sense of the war's wrongfulness persisted to the end of the text, in spite of the fact that everyone else, from his wife to Ka Vasudeva, told him the war was right and good; in spite of the fact that the dying patriarch Bhima lectured him at length on all aspects of the Good Law (the Duties and Responsibilities of Kings, which have rightful violence at their center; the ambiguities of Righteousness in abnormal circumstances; and the absolute perspective of a beatitude that ultimately transcends the oppositions of good versus bad, right versus wrong, pleasant versus unpleasant, etc.); in spite of the fact that he performed a grand Horse Sacrifice as expiation for the putative wrong of the war. These debates and instructions and the account of this Horse Sacrifice are told at some length after the massive and grotesque narrative of the battle; they form a deliberate tale of pacification (prasamana, santi) that aims to neutralize the inevitable miasma of the war.*/

Bhima Versus Duryodhana

“In the years that follow the war Dhtarara and his queen Gandhari [Gaan-DHAAR-ee], and Kunti [Koon-tee], the mother of the Paavas, lived a life of asceticism in a forest retreat and died with yogic calm in a forest fire. Ka Vasudeva and his always unruly clan slaughtered each other in a drunken brawl thirty-six years after the war, and Ka's soul dissolved back into the Supreme God Viu (Ka had been born when a part of Narayaa-Viu took birth in the womb of Ka's mother). When they learned of this, the Paavas believed it time for them to leave this world too and they embarked upon the 'Great Journey,' which involved walking north toward the polar mountain, that is toward the heavenly worlds, until one's body dropped dead. One by one Draupadi and the younger Paavas died along the way until Yudhihira was left alone with a dog that had followed him all the way. Yudhihira made it to the gate of heaven and there refused the order to drive the dog back, at which point the dog was revealed to be an incarnate form of the God Dharma (also known as Yama, the Lord of the Dead, the God who was Yudhihira's actual, physical father), who was there to test the quality of Yudhihira's virtue before admitting him to heaven. Once in heaven Yudhihira faced one final test of his virtue: He saw only the Dhartararas in heaven, and he was told that his brothers were in hell. He insisted on joining his brothers in hell, if that be the case. It was then revealed that they were really in heaven, that this illusion had been one final test for him. So ends the Mahabharata! */

Mahabarat Excerpt on Kingship

The following brief excerpt deals with the origins of kingship. “Yudhistira said: "This word raja [king] is so very current in this world, O Bharata [master]; how has it originated? Tell me that O grandfather." Bhishma said: "Certainly, O best among men, do you listen to everything in its entirety - how kingship originated first during the krtayuga [golden age]. Neither kingship nor king was there in the beginning, neither danda [scepter] nor the bearer of a danda. All people protected one another by means of righteous conduct, O Bharata, men eventually fell into a state of spiritual lassitude. [Source: “Sources of Indian Tradition,” ed., Stephen Hay (Columbia UP, 1988), Internet Archive, from CCNY |:|]

“Then delusion overcame them. Men were thus overpowered by infatuation, O leader of men, on account of the delusion of understanding; their sense of righteous conduct was lost. When understanding was lost, all men, O best of the Bharatas, over-powered by infatuation, became victims of greed. Then they sought to acquire what should not be acquired. Thereby, indeed, O lord, another vice, namely, desire overcame them. Attachment then attacked them, who had become victims of desire. Attached to objects of sense, they did not discriminate between what should be said and what should not be said, between the edible and the inedible and between right and wrong. When this world of men had been submerged in dissipation, all brahman [spiritual knowledge] perished; and when brahman perished, O king, righteous conduct also perished." When brahman and righteous conduct perished, the gods were overcome with fear, and fearfully sought refuge with Brahma, the creator. |:|

“Going to the great lord, the ancestor of the worlds, all the gods, afflicted with sorrow, misery, and fear, with folded hands said: 'O Lord, the eternal brahman, which had existed in the world of men has perished because of greed, infatuation, and the like, therefore we have become fearful. Through the loss of brahman, righteous conduct also has perished, O God. Therefore, O Lord of the three worlds, mortals have reached a state of indifference. Truly, we showered rain on earth, but mortals showered rain [i.e., gave sacrifices] up to heaven. As a result of the cessation of ritual activity on their part, we faced a serious peril, O grandfather, decide what is most beneficial to use under these circumstances." Then, the self-born lord said to all those gods: 'I will consider what is most beneficial; let your fear depart, O leaders of the gods.' |:|

Krishna and the Pandava Princes battle demons

“Thereupon he composed a work consisting of a hundred thousand chapters out of his own mind, wherein dharma [righteous conduct], as well as artha [material gain] and enjoyment of kama [sensual pleasures] were described. This group, known as the threefold classification of human objectives, was expounded by the self-born lord; so, too, a fourth objective, moksa [spiritual emancipation], which aims at a different goal, and which constitutes a separate group by itself. Then the gods approached Vishnu, the lord of creatures, and said: 'Indicate to us that one person among the mortals who alone is worthy of the highest eminence.' Then the blessed lord god Narayana reflected, and brought forth an illustrious mind-born son, called Virajas" who became the first king of India.” |:|

Bhagavad Gita

The “Bhagavad Gita” ("Song of God") is an epic poem consisting of 701 Sanskrit couplets. Part of the “Mahabharata”, it blends theology and political science with a dramatic story of dynastic struggle. According to legend it was written by the sage Vyasa. It probably existed independently of the “Mahabharata” and was added and revised to its present form around the A.D. 2nd century. Today, it is the most widely read Hindu text.

The “Bhagavad Gita” is essentially a devotional poem set among the battles of the “Mahabharata” . It outlines rituals accessible to everyone. This contrasts with the rituals described in old Vedic texts, which involved sacrifices and elaborate rites that were only open to upper castes. Many customs and fetishes have evolved around the “Bhagavad Gita” . Some people wear a miniature copy of it around their neck for luck and to ward off evil.

The “Bhagavad Gita” begins at the battlefield of Kurukshetra, a popular pilgrimage place today. Arjuna is brooding over the upcoming clash because he has friends, relatives and teachers on the other side. Krishna advises him to pour himself into the battle and not worry about the consequences, telling the warrior that is the only way he can find knowledge, freedom and peace.

Much of the text is made of dialogues between Krishna and Arjuna with Krishna encouraging Arjuna to fight and overcome his reluctance not to fight. Krishna tells Arjuna that he must fight because he is a warrior by caste and it is his duty to fight, saying: “For there is more joy in doing one’s duty badly that in doing another’s well. It is a joy to die doing one’s duty, but doing another man’s duty brings dread.”

According to the BBC: “The Bhagavad Gita, or "Song of the Lord" is part of the sixth book of the Mahabharata, the world's longest poem. Composed between 500 B.C. and 100 CE, the Mahabharata is an account of the wars of the house of Bharata. The Bhagavad Gita takes the form of a dialogue between Pandava Prince Arjuna and Lord Krishna, his charioteer. Arjuna is a warrior, about to join his brothers in a war between two branches of a royal family which would involve killing many of his friends and relatives. He wants to withdraw from the battle but Krishna teaches him that he, Arjuna, must do his duty in accordance with his class and he argues that death does not destroy the soul. Krishna points out that knowledge, work and devotion are all paths to salvation and that the central value in life is that of loyalty to God.” [Source: BBC]

See Separate Article BHAGAVAD GITA factsanddetails.com

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Internet Indian History Sourcebook sourcebooks.fordham.edu “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “Encyclopedia of the World's Religions” edited by R.C. Zaehner (Barnes & Noble Books, 1959); “Encyclopedia of the World Cultures: Volume 3 South Asia” edited by David Levinson (G.K. Hall & Company, New York, 1994); “The Creators” by Daniel Boorstin; “A Guide to Angkor: an Introduction to the Temples” by Dawn Rooney (Asia Book) for Information on temples and architecture. National Geographic, the New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Times of London, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton's Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated September 2020