AWARD WINNING ZHANG YIMOU'S FILMS

Poster for Red Sorghum Zhang Yimou is one of world’s premier directors as well as a screenwriter, producer, actor, and cinematographer. Regarded along with Chen Kaige as a leader of the Fifth Generation of Chinese cinema, he helped bring Chinese film to an international audience. After graduating of Beijing Film Academy, Zhang began his career as a cinematographer and an actor. He directed his first film, the widely acclaimed “Red Sorghum”, in 1987. By 2004 he had made 15 other movies, about of which are regarded as masterpieces. [Source: John A. Lent and Xu Ying, “Schirmer Encyclopedia of Film”, Thomson Learning, 2007]

John A. Lent and Xu Ying wrote in the “Schirmer Encyclopedia of Film”:“Zhang's films are distinguished by rich cinematography and an emphasis on imagery and metaphors to convey messages, and until recently, they have featured dark, mournful, folkloric stories of rural life. They often deal with the perseverance of Chinese commoners, whether it is the family in “To Live” (1994) trying to survive the unpredictable reality of the 1940s to 1980s; the wife in “Story of Qiu Ju” (1992), who repeatedly goes back to court to seek justice for her abused husband; Wei Minzhi in “Not One Less” (1999), who doggedly fulfills her assignment to keep a class of students together; or the mother in “The Road Home” (1999), who stubbornly insists that her deceased husband be returned home against formidable odds to be given a traditional burial. Color also plays a key role in Zhang's films: in Da hong deng long gao gao gua (Raise the Red Lantern, 1991), the dominance of the wedding color red, which represents which wife is chosen for the conjugal bed; the bright colored cloth hanging in the dye house in Ju Dou (1990), which contrasts with the dull unhappiness of the young, unfaithful wife; and the colorful countryside in The Road Home, which hints at the happiness of the parents when they were young and in love.

Zhang Yimou's “Ju Dou” was the first Chinese film to be nominated for an Academy Award. “Raise the Red Lantern”, also by Zhang, was the second. “Red Sorghum” (1987) won the Golden Bear Award in Berlin. Based on a semi-autobiographical short story by the writer Mo Yan, it is about a young village girl played by Gong Li who is forced to marry a disgusting old wine factory owner,. On her way to the wedding she abducted by bandits in a sorghum and then is abducted again, with the film being a succession of surprises. “To Live” (1994), about a couple that survived the Great Leap Forward and the Cultural Revolution, won Grand Prix Du Jury Award an Cannes. It takes place over four decades, ending with the Cultural Revolution.

“Ju Dou” (The Story of Qiu Ju, 1992) also with Gong Li won the Golden Lion at the Venice Film Festival. It is about a couple’s rebellion against a decadent tyrant. Gong Li plays woman forced into a marriage with an impotent old textile mill owner. The final scene with the big fire was added after Zhang witnessed the aftermath of the Tiananmen square massacre. “Gong Li plays a pregnant woman who seeks justice after a village chief kicks her husband in the testicles in a remote villages. Her quest involves traveling to a distant city to seek the help of officials that want to have nothing to do with her. Based on the novella “The Wan Family’s Lawsuit” by Yuan Bin Chen, it is a simple story told very well, involving compelling, understated characters and set in rural China depicted with amazing authenticity. Most of the people in the film are real villagers.

“Not One Less” won the Golden Lion at the Venice Film Festival in 1999 after Zimou had pulled it from Cannes. The story of villager who locates a lost student with the help of a benevolent state television boss, it is an interesting and endearing film set in a poor rural school with a cast of children, the oldest a 13-year-old schoolgirl, who plays the school’s barefoot teacher. The film takes unflattering look at a school in a poor area of China. The school looks like shack and suffers from a chronic shortage of chalk.

“The Road Home” (2000) won the Silver Bear Award at the 2000 Berlin Film Festival. Starring Zhang Ziyi as a charming and delightful peasant girl, it is a charming, minimalist story about a girl’s crush on a young man that visits her village. I love this film.

See Separate Articles: CHINESE FILM factsanddetails.com ; FIFTH GENERATION FILM MAKERS OF CHINA factsanddetails.com ; ZHANG YIMOU: HIS LIFE AND PROJECTS factsanddetails.com ; ANG LEE AND HIS FILMS factsanddetails.com

Websites: Zhang Yimou at IMDB imdb.com ; Chinese Film Classics chinesefilmclassics.org ; Senses of Cinema sensesofcinema.com; 100 Films to Understand China radiichina.com. dGenerate Films is a New York-based distribution company that collects post-Sixth Generation independent Chinese cinema dgeneratefilms.com; Internet Movie Database (IMDb) on Chinese Film imdb.com ; Wikipedia List of Chinese Filmmakers Wikipedia ; Shelly Kraicer’s Chinese Cinema site chinesecinemas.org ; Modern Chinese Literature and Culture (MCLC) Resource List mclc.osu.edu ; Love Asia Film loveasianfilm.com; Wikipedia article on Chinese Cinema Wikipedia ; Film in China (Chinese Government site) china.org.cn ; Directory of Interent Sources newton.uor.edu ; Chinese, Japanese, and Korean CDs and DVDs at Yes Asia yesasia.com and Zoom Movie zoommovie.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: “Encyclopedia of Chinese Film” by Yingjin Zhang and Zhiwei Xiao Amazon.com; “The Chinese Cinema Book” by Song Hwee Lim and Julian Ward Amazon.com; “The Oxford Handbook of Chinese Cinemas by Carlos Rojas and Eileen Chow Amazon.com; “Chinese National Cinema” by Yingjin Zhang Amazon.com; “Zhang Yimou: Interviews” edited by Frances Gateward, Amazon.com; “Globalization and Contemporary Chinese Cinema: Zhang Yimou's Genre Films” by Xuelin Zhou Amazon.com; “Memoirs from the Beijing Film Academy: The Genesis of China's Fifth Generation” by Ni Zhen Amazon.com; “Representation of the Cultural Revolution in Chinese Films by the Fifth Generation Filmmakers: Zhang Yimou, Chen Kaige, and Tian Zhuangzhuang” by Ming-May Jessie Chen, Mazharul Haque, et al. Amazon.com; “General History of Chinese Film III” by Ding Yaping Amazon.com; “Chinese Films in Focus II” by Chris Berry Amazon.com; “Contemporary Chinese Cinema and Visual Culture: Envisioning the Nation” by Sheldon Lu Amazon.com; “Reinventing China: A Generation and Its Films” by Paul Clark Amazon.com

Recommended Zhang Yimou Films : “Red Sorghum (1987), “Ju Dou” (1990), “Raise the Red Lantern” (1991), “Story of Qiu Ju” (1992), “To Live, 1994", “Not One Less” (1999), “The Road Home” (1999), “Happy Time” (2001), “Hero” (2002) and “House of Flying Daggers” (2004)

Red Sorghum

Red Sorghum

“Red Sorghum” (1987), a saga of life in rural Shandong during the Japanese invasion in the 1930s and 1940s, was written by literature Nobel-Prize winner Mo Yan and remains Mo’s most celebrated work. Set in Mo’s native Gaomi, Red Sorghum spans a chronology that begins in the 1920s and culminates in the war with Japan. Mo and the book became famous in the late 1980s when the filmmaker Zhang Yimou made the novel into a prize-winning film. [Source:Week in China, April 12, 2013 ^*^]

According to Week in China: “In one striking incident in Red Sorghum, a village virgin is deflowered by a soldier. The upright Adjutant Ren speaks to his superior Commander Yu, asking: “If a Japanese raped my sister, should he be shot?” The answer: of course! “If a Chinese raped my sister, should he be shot?” Again, the reply: of course! Following this logic, Ren then says: “That’s just what I wanted to hear. Big Tooth Yu deflowered this local girl… When will he be shot Commander?” But Big Tooth Yu is the commander’s uncle, so his response changes dramatically. “Since when is sleeping with a woman a serious offence?” Yu declares, before suggesting an alternative punishment: 50 lashes and compensation for the family of 20 silver dollars. Nor is Yu even the villain of the story: in fact, he’s the closest thing the novel has to a ‘hero’.

Perry Link wrote in the NY Review of Books: Liu Xiaobo, the Nobel-Peace- Prize-winning dissident, who knew Mo Yan, later wrote that one reason for the film’s tremendous success was that “it drew freely upon the themes of raw sexuality and adultery. Its theme song, ‘sister, be gutsy, go forward,” was an unbridled endorsement of the primitive vitality of lust. Against the backdrop of fire-red sorghum in desolate northwestern China, under the broad blue sky and in full view of the bright sun, bandits violently abduct village women, wild adultery happens in the sorghum fields, bandits murder one another in competition for women, male laborers magically produce the widely renowned liquor “Six-Mile Red” by urinating into the heroine’s brewing wine, and so on...All of this---not only sets the scene for marvelous consummations of male and female sexual desire; it creates a broader dream vision that carries magical vitality. That Red Sorghum could win prizes symbolizes a change in national attitudes towards sex: “erotic display” had come to be seen as “exuberant vitality.” Mo Yan points out, correctly, that Red Sorghum took considerable heat from the authorities in the 1980s. The work not only defied sexual taboos; it portrayed a version of Chinese life under Japanese occupation that was radically at odds with official Communist accounts of heroic peasant resistance. Mo Yan, Zhang Yimou, and others were viewed as young rebels. [Source: Perry Link, NY Review of Books, December 6, 2012]

Raymond Zhou wrote in the China Daily: “ Red Sorghum jump-started many high-octane careers, including Zhang Yimou as China's pre-eminent filmmaker and Mo as a major literary figure. Both have acknowledged the other's contribution to their mutual success. For Mo, "without the movie, I'd have been known only within literary circles". However, the experience also exposed his ignorance about filmmaking as an art form separate from literature. When Mo first saw Gong Li on the set, he was not impressed. "She looked like a college girl to me, without any trace of the female lead I envisioned for the part," he said. "She would ruin the movie." In addition, the thick script he helped adapt from his own work was slashed by Zhang to only "seven or eight pages". The end result, of course, took him by surprise. The five-minute bridal sedan scene alone leapt from page to screen with striking visuals and unforgettable energy. "And I was so wrong about Gong Li," he said. [Source: Raymond Zhou, China Daily, October 12, 2012]

In 1987, Mo earned 800 yuan for the rights to Red Sorghum. That was in addition to the 1,200 yuan he got as one of three writers for the script. "I was so excited I was awake the whole night. Nowadays, 800 is a pittance. Some writers make millions by selling the movie rights to their novels." Mo has been left wiser after his occasional forays into the business of films. "Do not think of movie stuff when you write a novel. Do not pander to directors. It's their job to pick what's useful to them from the novels."

Raise the Red Lantern

Scene from Raise the Red Lantern “Raise the Red Lantern” (1991) with Gong Li won the Silver Lion Award at the Venice Film Festival and was nominated for an Academy Award for best foreign film. It is about the unhappy, rich man’s third wife who is preyed upon by the man’s previous wives. The lantern in the title refers to the lantern that is hung identifying the wife the master wants to sleep with. Director Steven Spielberg called “Raise the Red Lantern” Zhang’s magnus opus and wrote, the vivid use of red in the manufacturing of wine, the traditional wedding gown, the process of dying silk and even the crimson splashes of blood illuminate Zhang’s celebration of life, exoticism and death.”

Raise the Red Lantern is based on the novella “Wives and Concubines” (1989) by Su Tong, who is known for dark, provocative works which have been popular but have sometimes put him at odds with the authorities. Su Tong burst onto the Chinese literary scene in the mid-eighties. Since then, his prolific and provocative work’seven novels, a dozen novellas, over 120 short stories, with translations available in a dozen languages. He won the 2009 Man Asian Literary Prize for his novel “The Boat to Redemption”.

Su is known as a writer who deals sympathetically with women and their feelings. Some of works also contain a fair amount of violence and abuse. When questioned about the violence in his works, Su said he often asks himself the same question. But he argues that what matters is how people deal with the violent legacy of bygone times. “I won't write a novel based on violence. But when I try to capture the bloody smell of iron typical of that time, I shall never avoid it,” Su told the China Daily.

To Live

“To Live” is based a novel by Yu Hua, a popular Chinese writer who is known as both a literary master and dispenser of pulp schlock who has won commercial success by tossing out shocking and disgusting images and episodes. He has been praised by foreign critics and is frequently mentioned as a likely candidate for the Nobel Prize in Literature. Yu is the author of “Chronicle of a Blood Merchant” and “Brothers” as well as , “To Live. Yu made his name in the late 1980s with a series of disturbing short stories. Since then he has written several novels and volumes of essays; and refined the art of circumventing censorship.

“To Live” is Yu Hua’s acclaimed 1993 tale of a Chinese Everyman’s experiences through decades of revolutionary upheaval. Jeffrey Wasserstrom wrote in the LA Review of Books, “It’s a little gem of a book, alternately funny and poignant, which somehow manages to feel epic despite its modest page count and tight focus on a small set of characters.” The book boasts a broad scope, addressing not only the Cultural Revolution but the Nationalist era (1927-1949), as well as the early Mao years that preceded and in some ways set the stage for it. [Source: Jeffrey Wasserstrom, LA Review of Books, November 12, 2011]

Ian Johnson wrote in the New York Review of Books: "To Live", recounts in parable-like form the story of a peasant who endures China’s civil war and then the famines and political campaigns of early Communist rule. His main quality is his sheer will to live, making the novel a bleak commentary on recent Chinese history. The novel sold more than 200,000 copies in 2011 in China, according to his publisher, the Writers Publishing House. [Source:Ian Johnson, New York Review of Books, October 11, 2012]

“Like any talented novelist in China, Yu has always walked a fine line: To Live was made into an acclaimed movie by the Chinese director Zhang Yimou but it was banned in China, even though Zhang toned down Yu’s most caustic criticisms. (In the most notorious scene in the novel, the hero’s son has his blood drained by a provincial doctor eager to save the life of a top official; the movie makes his death an accident.)

Evolution of Zhang Yimou Films

Chris Lee of the Los Angeles Times wrote Zhang’s “films have generally fallen into two categories. There are his gritty epics, such as “Ju Dou’ and “To Live” from his early filmography, that showcase China's struggles with war, poverty and political malfeasance (and have been consequently banned in the director's homeland for ‘subversive’ content). And then there are his more recent martial arts thrillers, such as “House of Flying Daggers” or “Hero” — films that critics complain implicitly glorify the Chinese state and have won Zhang favoritism with the political elite while also saddling him with a reputation as a kind of Leni Reifenstahl for China's authoritarian regime.”

“As he shifted to the martial arts epics, Zhang was criticized as selling out to the Chinese government and pandering to what officials wanted,” Micheal Berry, associate professor of Contemporary Chinese Cultural Studies at UC Santa Barbara, who extensively interviewed the director for his book “Speaking in Images: Interviews With Contemporary Chinese Filmmakers” , told the Los Angeles Times, “He's always rejected those criticisms, though. It's a natural evolution. People tend to be rebellious when they're young and after a while, they become the establishment.

Poster for Road Home

After the success of Ang Lee’s “Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon” Zhang began to make more commercial films. “House of Daggers” (2004), another martial arts epic with Zhang Ziyi. premiered with much acclaim at the Cannes Film Festival in 2004. Set during the Tang dynasty, it showcases Zhang as a blind martial arts master and was described by Time “zippier, more cunning” than Hero but criticized by others for having a confusing plot and weak ending Both Hero and House of Daggers both seemed like attempts to produce films that would delight the Beijing censors and foreign critics and audience.

It is somewhat surprising that Zhang took up martial arts. When he was growing up during the Cultural Revolution it was a crime to watch or even read about kung fu or the martial arts, he didn’t see a Bruce lee movie until 1979 and as of 2005 he said he only watched about a dozen and half martial arts films.

“Riding Alone a Thousand Miles” is a film by Zhang starring the Japanese actor Ken Takakura. It is about a father who goes to China to see his critically ill son and their last chance to med fences. Wearing Golden Armor Across the City features Gong Li as an Empress and Chow Yun-fat as an Emperor, The film was the first time Zhang and Li had worked together in more than decade.

“Curse of the Gold Flower” (2006) is blockbuster, costume drama about an imperial family that turns on itself with an emperor trying to poison his wife and the empress unleashing her there sons against their father with all three meeting brutal, violent ends. Starring Chow Yun-fat and Gong Li, it was named one of the 10 Best Movies of the Year by Time magazine but was criticized by Chinese critics as lavish but lacking in substance, showing too much cleavage and being to violent. One Chinese critic called it a “bloodthirsty movie” and said that after watching it he had a “feeling of nausea that would not go away.” At $45 million it is the costliest film ever made in China

Zhang Yimou was originally slated to make the “The Founding of a Republic”, a 2009 patriotic blockbuster that depicts Mao Zedong rise to power, released to mark the 60th anniversary of the founding of Communist China. In the end Han Sanping directed it.

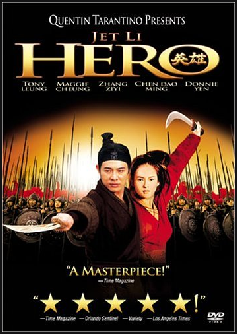

Hero

”Hero” (2002) is a big-budget, big-name, Hollywood-style epic star film directed by Zhang. Described by Time magazine as a “a masterpiece” and by the Los Angeles Times as a “visual knockout,” it is a dazzling, visual film, noted for its stunning use of color and imaginative use of “Crouching Tiger”-style digitalized action sequences. The censors in Beijing liked it too but some international critics condemned it as overproduced and silly and some Chinese critics claimed it promoted servility and glossed over the horrible things done by the ancient ruler Emperor Qin.Some critics panned Hero as being an “implicit homage to authoritarian rule." Government critics hailed it as a “new starting point."

“Hero” is based on the story of a 3rd century B.C. assassin who had an opportunity to kill the great Emperor Qin but failed to do so. Like the classic “Rashomon”, a single story is told several times from different perspectives as the assassin struggles to overcomes three rivals. The film is divided into three main sections, each dominated by a single color — red, blue and white, with green thrown in for flashbacks. The blue scenes were shot at the beautiful lakes in the Jiuzhaigou region of China and were said to be inspired by the lake’s color. The white scene were shot in desert near the Kazakhstan border.

“Hero” was the most internationally successful Chinese film export until the mid 2000s and remains one of the top-grossing foreign-language films to appear in American theaters. Costing $30 million to make, Hero features grand battle scenes, martial art choreography and big names like Jet Li, Tony Leung, Maggie Cheung and Zhang Ziyi. It was a box office smash in China, where it ranked second only to Titanic as the highest grossing film ever in China. The United States version— with an imprimatur from Quenton Tarantino and with 20 minutes edited out to speed up the pace and make it more palatable to American audiences — came out in 2004. It broke box office records there for an Asian film. As of early 2005 it had earned $53.5 million in the United States and $155 million worldwide. The Chinese government lobbied hard to get the film an Academy Award nomination in 2002 for best foreign film and then lobbied hard to get it to win.”

“Hero” was the most internationally successful Chinese film export until the mid 2000s and remains one of the top-grossing foreign-language films to appear in American theaters. Costing $30 million to make, Hero features grand battle scenes, martial art choreography and big names like Jet Li, Tony Leung, Maggie Cheung and Zhang Ziyi. It was a box office smash in China, where it ranked second only to Titanic as the highest grossing film ever in China. The United States version— with an imprimatur from Quenton Tarantino and with 20 minutes edited out to speed up the pace and make it more palatable to American audiences — came out in 2004. It broke box office records there for an Asian film. As of early 2005 it had earned $53.5 million in the United States and $155 million worldwide. The Chinese government lobbied hard to get the film an Academy Award nomination in 2002 for best foreign film and then lobbied hard to get it to win.”

Some critics accused Zhang of selling out to Hollywood. Zhang responded that he was developing a style that was international and modern. “China has stepped into a new era, an era of consumption and entertainment. You can condemn it if you like, but it is a trend of globalization.” Zhang was critical of the way Mirimax cut the American verison of “Hero”. He wrote them, “If you insist on doing nothing to support the film but keep on delaying and cutting down the movie, and eventually destroying it, I cannot imagine how the Chinese government and the whole Chinese population will think of you and Mirimax...I truly believe, no one cold stop their anger! You will be hurting not only me, but also the whole Chinese population.”

Zhang Yimou Remakes Blood Simple as a Slapstick Musical

In 2010, Zhang released “A Simple Noodle Story”, a visually-lush, radical remake of “Blood Simple” , the 1984 Joel and Ethan Coen nerve-jangling noir thriller set in a Texas bar. The story revolves around the chain of events when a good-for-nothing bar owner hires a detective to kill his wife and her lover. Zhang's version transplants the action to a remote noodle shop in ancient China, leaving much of the storyline intact and using some identical shots.[Source: National Public Radio, January 4, 2010]

Zhang told NPR he set the film in the past for the sake of ease. “It's more convenient setting it in ancient China. The level of freedom is greater. It's not that easy to shoot contemporary material. Lots of things are forbidden,” he said. The surprise is the director's decision to remake the movie as a slapstick comedy with song-and-dance numbers revolving around noodle-making. The cast includes some of China's top comedians: Xiao Shenyang as a nervous girly guy and Zhao Benshang as a goofy character with buck teeth who falls down almost every time he appears.

“It's very absurd, very exaggerated,” Zhang told NPR unapologetically. “It's because I shot such serious films before, I wanted to experiment with a different style. In fact, there were commercial factors. We wanted to make a New Year film,” he said. Chris Lee wrote in the Los Angeles Times, “The film situates “Blood Simple's” double-crosses and misunderstandings, grand mal scheming and thievery, in desolate Gansu province, somewhere between the Great Wall of China and the Silk Road, during the late Ming dynasty of the 17th century. The original film's perfidious private eye, oily gin-joint owner and his wife have been respectively reincarnated as a granite-faced local constable with a gigantic sword, a curmudgeonly restaurateur and a shrill adulteress with a gymnastic talent for making hand-pulled noodles. “As well, where “Blood Simple” exists almost as a formal exercise in the cinematic usage of darkness, shadows and light, color fairly explodes from the screen in “A Woman, a Gun.” And with several of China's most beloved comedians in prominent roles, it is also shot through with a goofy brand of Peking Opera-inspired comedy that has proved somewhat baffling to many non-Chinese viewers.

In the United States and Europe the film was released under the name “A Woman, a Gun and a Noodle Shop”. The $12-million film premiered at the Berlin Film Festival in 2009. It got relatively good press from Variety, Indiewire and Slash Film. Sony Pictures Classics distributed it. Zhang told the Los Angeles Times the Coens saw an early cut of “A Woman, a Gun” and gave it their approval. “They thought it was fun and interesting the way we took their contemporary film, added Chinese flavor and set it in the past,” the director said. “They never imagined their film could be expressed in this manner.” According to Wong, the adaptation may have unintentionally opened the door to a kind of cross-cultural movie exchange program. “They sent a note of congratulations to Zhang,” Wong said. “They told him that they are going to make a remake of 'Raise the Red Lantern.'”

Zhang Yimou's "Hawthorn Tree"

Alexandra A. Seno wrote in the Wall Street Journal, “After a decade of working on spectacles like the 2008 Olympics ceremonies, leading Chinese filmmaker Zhang Yimou has returned with an intimate, low-budget drama set in the Cultural Revolution. “Under the Hawthorn Tree” features young, unknown actors in lead roles and was shot for under 65 million renminbi ($10 million). It has already brought in more than 150 million renminbi in China, according to its producer, Bill Kong, setting a box-office record for a drama by Mr. Zhang, one of the country's few high-culture filmmakers with mass appeal.” [Source:Alexandra A. Seno Wall Street Journal, November 19, 2010]

Based on a popular novel, “Under the Hawthorn Tree” is a love story set during the Cultural Revolution. It tells the story of the son of a Communist Party official (played by Shawn Dou) and the daughter (Zhou Dongyu) of a jailed political outcast in 1970s China. Ms. Zhou's character, Jingqiu, is based on a real person whose identity has never been made public, but whose diaries formed the basis of a biography that, in turn, became an online sensation, widely read on the Internet.”

“The 1970s, when "Hawthorn Tree" is set, have recently been much romanticized in pop culture on the mainland for being a simpler time, of "purer" values. Interviewed by phone from Beijing, where he is based, Mr. Zhang says that he looks back on those years as a formative part of his youth. After a nationwide search where he auditioned over 6,000 actors in 16 cities, he chose Mr. Dou and Ms. Zhou because 'they looked "very clean," much like the people of that era.” The small-scale film contrasts sharply with big-budget affairs that Mr. Zhang has made in recent years.

Flowers of War

Flowers of War (2011) was a Chinese-Hollywood co-production about the Rape of Nanking in 1937, starring Christain Bale. Steven Zeitchik wrote in the Los Angeles Times, “In a sign of the growing East-West cooperation in filmmaking, Christian Bale, the on-screen incarnation of Bruce Wayne and his caped alter ego, is starring in "The Flowers of War," a $94-million movie that is China's submission for the foreign-language Oscar this season. Directed by Zhang Yimou, "Flowers" shows how people from radically different backgrounds can come together to create a movie with potentially broad appeal. The film is, after all, a uniquely Chinese story told largely through a veteran actor of Hollywood blockbusters. [Source: Steven Zeitchik, Los Angeles Times, December 11, 2011]

"Partially funded by the state, following increased government investment in the media and culture industries, “The Flowers of War” is China's most expensive film. Adapted from a novel by Geling Yan, it also shows how that combination can pose challenges — particularly on the question of language. The film contains dialogue that's about 60 percent Mandarin, with the rest in English."I didn't speak a word of English, so I really needed to trust Christian," Zhang said in Mandarin, via a translator.

For his part, Bale, who does not speak any Mandarin, said it was a difficulty they were able to overcome. "It's amazing how much you can have a language barrier and still break down a communication barrier," the actor said in an interview with Zhang recently in Los Angeles. "I was able to communicate better with Zhang than with many English-speaking directors."Their linguistic bridge was Zhang Mo, the director's 28-year-old-daughter and aide de camp, who speaks Mandarin and English fluently and was a frequent presence on set.

In the 145-minute film, Bale plays John Miller, a carpetbagging American mortician looking to make a quick buck in China as the Japanese invade the city of Nanjing in 1937. When he holes up in a Catholic boarding school where teenage students and prostitutes have taken refuge from the fighting, Miller suddenly finds himself responsible for their welfare. As the horrors of the war close in — a Japanese commander, for instance, demands that the girls "sing" for officers at a military parade, code for rape — Miller is given a crash course in atrocities as well as his own capacity for sacrifice.

The Bank of China is among those funding The Flowers of War, which was released in early December 2011 at more than 8,000 screens in China and then released in the U.S. and Europe. The film had trouble finding a U.S. distributor, took 164 day to shoot and assumes knowledge of the historical period in which it takes place. The Guardian reported: "Reviews of “Flowers of War” criticized its poor plot, commercial vulgarity, wooden acting and propagandist message. Released just days after the anniversary of the 1937 Nanking Massacre, the film looks set to stir up nationalist passions, both over the country's historical grievances and its modern cultural ambitions. There is no more sensitive subject in modern Chinese history than the "Rape of Nanking” as the massacre become known in the west. Dramatisations of the killings have been a staple of Chinese films since the black-and-white propaganda epics of the Mao era. But the new big budget production adds racier dialogue, image makeovers and hi-tech gore.” [Source: Jonathan Watts and Justin McCurry, The Guardian, December 15, 2011; [Source: Steven Zeitchik and David Pierson, Los Angeles Times, July 03, 2011]

Coming Home

““Coming Home” (2014) was maybe one of the better films that Zhang made in the 2010s. Didi Kirsten Tatlow wrote in the New York Times’ Sinosphere blog: The film “about the ravages wrought on a family by decades of political violence in China and how they (kind of) overcome them, stars Gong Li, his legendary muse. It made Steven Spielberg cry, the Chinese news media reported. Ang Lee, the Academy Award-winning director of “Life of Pi,” was “very moved” by it too, he said on Chinese television. “Coming Home” was widely expected to be a shoo-in as China’s submission to the Oscars in 2015 for films in 2014 but instead “The Nightingale,” a small-budget film directed by Frenchman Philippe Muyl was been chosen. Even the film’s makers were shocked. [Source: Didi Kirsten Tatlow, Sinosphere blog, New York Times, May 9, 2014]

Eva Shan Chou wrote in China File: “Coming Home” “begins as a man escapes a labor camp in China’s northwest and tries to return home. But he is captured when he and his wife attempt to meet, after their daughter turns him in in exchange for the promise of the lead role in the ballet The Red Detachment of Women. The rest of the movie takes place three years later, in 1976, after the Cultural Revolution has ended. The man, Lu Yanshi, is politically rehabilitated and allowed to return home, but his wife no longer recognizes him. The movie then follows his successive stratagems, aided by his daughter, to rouse her memory; eventually, he accepts a role that allows him to remain near to her — reading aloud his own letters to her as if he were not the one who had written them. [Source: Eva Shan Chou, China File, October 2, 2015]

“The film reflects a familiar pattern of Zhang’s: tight focus on a man and a woman plus a younger person, treated with a closed-off intensity that draws the audience into a situation that becomes more and more unusual, set against a backdrop of momentous events in Chinese history. The cinematography and pacing are those of a master. The performances he elicits from his actors are excellent: Chen Daoming gives an especially fine performance as Lu; Gong Li, Zhang’s one-time muse, plays his wife, Feng Wanyu; the newcomer Zhang Huiwen is their daughter, Dandan. The result is an immensely moving film about the human cost of history, the survival of love, and the reconstitution of a family.

“And yet. And yet, the film seems to use history mainly to increase pathos; there is no real engagement with historical events. In China, Coming Home set a record for box office receipts for art films, grossing 295 million RMB in its first two weeks. But given the extent of official censorship, it’s a safe bet that almost no one under 35 in the audience had any prior knowledge of the events that form the backdrop to the story, or of any other traumatic events in post-1949 Chinese history. Nor, after viewing Coming Home, would such a person have learned much more. Reviews on the film’s release in the U.S. seem to reflect a similar disconnect with the past — they appreciate that history is the cause of the characters’ misery, but the film doesn’t help them understand that history any more deeply. Zhang’s sidestepping of sensitive topics seems consistent with the important commissions that he has received from the Chinese government, most notably the huge-scaled opening and closing ceremonies of the 2008 Olympics in Beijing.

“By contrast, in the Chinese-language press, critics in Hong Kong and Taiwan have found fault with the near-total displacement by the love story of anything resembling a historically accurate portrayal of the devastation wreaked by the Cultural Revolution. (Indeed, it is unlikely that the wife and daughter of a reactionary Rightist would live in a two-room apartment with its own kitchen and a piano and framed calligraphy.) These critics point out that the novel on which Coming Home is loosely based deals with the entire life span of its protagonist and that its author, Yan Geling, grapples with history much more fully. “

Great Wall: “Watching it Feels like Repeatedly Banging Your Head Against One”

“Great Wall” (2016), with Matt Damon, and Willem Dafoe working alongside Chinese stars including Andy Lau, Zhang Hanyu and Eddie Peng, was the first movie to emerge from Hollywood company Legendary Entertainment after it was bought by Chinese billionaire Wang Jianlin. One of the worst films every made by Zhang,it did okay at the box office in China but was largely panned and flopped outside China. Moviegoers in China are known their no-punches skewering of big-budget, low-quality offerings and Great Wall seemed to fit the bill for that. Zhang Yimou “has already died,” one person posted on the popular site Douban. Nearly all of the most-liked user reviews were in a similar vein, “Zhang Yimou finally unloaded the burden of being an artist, glamorously turned around, and told his former self, ‘goodbye!’”, another person posted [Source: Robbie Collin, The Telegraph, February 16, 2017]

Produced by the American company Legendary Entertainment in partnership with Universal Pictures, China Film Company and Le Vision Pictures, “Great Wall” cost $150 million to make but, according to Variety, even before it came out it came "under fire for positioning Damon’s lead character as a potential stereotype as a “white savior.” Actress Constance Wu criticized the casting when she wrote, “We have to stop perpetuating the racist myth that only a white man can save the world… Our heroes don’t look like Matt Damon.”

Under headline “Great Wall, Review:'Watching it Feels like Repeatedly Banging Your Head Against One', Robbie Collin wrote in The Telegraph: This fantastically tedious eyesore — a bilingual fantasy epic — allegedly heralds a new era of artistic collaboration between Hollywood and China, as that country’s cinema-goers become a dominant force at the global box-office. As things have turned out, it’s hard to think of an equivalent-but-in-reverse cultural mélange that could match it for sheer, tin-eared fatuousness: perhaps a CGI-heavy remake of Gone with the Wind that swapped out Rhett Butler for Fu Manchu.

“Matt Damon stars as a medieval Irish mercenary who finds himself in Song Dynasty China on a quest to find gunpowder — the fabled substance that “turns air into fire” — which he hopes to bring back to the West. His search takes him not to a city or a busy port, as you might expect, but the middle of a vast and almost entirely uninhabited desert, where one night he and his travelling party are attacked by a monstrous beast. Damon kills it and its body tumbles down a hitherto-unseen bottomless pit, but he manages to lop off a paw, which a local Chinese garrison identifies as belonging to a Tao Tie — a man-eating, four-legged Orc thing, seemingly millions of which live inside a nearby crashed meteor. Every 60 years they emerge en masse and lay siege to the Great Wall of China, in the hope of reaching the nearby ancient capital of Bianliang and feasting on the residents.

“The screenplay, credited to six writers including Max Brooks, Tony Gilroy and Edward Zwick, is more hole than plot, and sounds like an 1980s action-figure cartoon. Lame comic asides touch down with a plop, while the repartee between Jing and Damon’s characters seems to chill the very air around them. (The two actors have a strange and terrible kind of anti-chemistry.) When Willem Dafoe’s hollow-cheeked cleric emerges from behind a parapet, it looks as if some fun might finally be in store, but he turns out to be nothing more than the motor for a half-formed escape subplot which feels like leftovers from an earlier script. From blundered opening to risible conclusion, it’s a wall-to-wall fiasco.

One Second and Shadow

Zhang Yimou’s “One Second,” set during China’s 1966-76 Cultural Revolution, was pulled at the last second from the 2019 Berlin Film Festival, where it was to premiere in competition. A post on the film’s official Weibo social media site said it due “technical reasons.” “Though Zhang had touted “One Second” as his personal tribute to cinema, speculation immediately arose that the film was withdrawn for political reasons. As of late 2021 the film had still not been released. [Source: Patrick Frater and Nick Vivarelli, Variety, February 11, 2019]

The world premiere of Zhang Yimou's period historical epic "Shadow" (2018) took place at the 75th Venice International Film Festival. According to Chinese government media its “oriental aesthetics..wowed the audience.” Zhang said:"A shadow must seamlessly meld with reality, so that true and false can't be distinguished. I liked the idea of these political substitutes - the body doubles whose stories have never been told before." [Source: Zhang Rui, China.org.cn, September 9, 2018]

According to Xhina.org: Set in the period of the Three Kingdoms in Chinese history in the third century, it tells the story of a "nobody" imprisoned since he was eight-years-old and refuses to accept his fate as a puppet double, fighting his way to regain his freedom. Deng Chao plays two roles in the film; one as a local military officer, the other as the officer's shadow double. It is interesting to note, the actor's real-life wife, actress Sun Li, plays the officer's wife in the film.Zhang was also awarded the Jaeger-LeCoultre Glory to the Filmmaker prize, which is dedicated to "a figure who has left a particularly original mark on contemporary cinema." This award is rewarded to people with innovative spirit. I regard it as a kind of affirmation and encouragement for me," Zhang said when accepting the award at the premiere.

“Demetrios Matheou from Screen Daily wrote after the screening: "There's a particular adjustment in Zhang Yimou’s latest foray into martial arts action, namely the decision to base his visual style on the ink brush technique of Chinese painting. A director known for the sumptuous coloring of his epics now works in a virtually consistent monochrome palette. The result is striking and, unsurprisingly, just as beautiful." Zhang explained that in order to achieve the visual style of his film, he did not rely on computer effects, but rather created sets that were "as complete as a painting" in terms of design, costumes, makeup, and lighting, while the battle scenes involved a month of shooting in the rain.

Cliff Walkers

“Cliff Walkers”, Zhang Yimou spy thriller, starring Liu Haocun, was released in April 2021 and enjoyed moderate success in China and some moviegoers like it. But as The South China Morning Post said it “deceives with its labyrinthine narrative”. “ Full of exhilarating action, the plot of this thriller, set in 1930s Manchuria, is overstuffed. Liu Haocun shines as the doe-eyed yet tough heroine, but the rest of the cast are forgettable. [Source: James Marsh, South China Morning Post, April 30, 2021]

James Marsh wrote in“Zhang Yimou’s Cliff Walkers bursts at the seams with lavish visuals and a slew of exhilarating action sequences, as one might expect from the director of Hero and House of Flying Daggers. Recalling everything from Where Eagles Dare to The Age of Shadows, this snow-driven spy caper delivers enough betrayals and double-crosses to make John le Carré seem like Tintin. However, the film’s labyrinthine narrative deceives and confounds its audience as readily as the protagonists, as we collectively struggle to recall exactly who is fighting on whose side.

“Liu Haocun, Zhang’s latest ingénue and star of his still unreleased previous film, One Second, plays one of four Soviet-trained agents who parachute into 1930s Japanese-occupied Manchuria on a mission to rescue a witness who can expose Japan’s atrocities to the world. Two team members, Yu (Qin Hailu) and Chuliang (Zhu Yawen), are apprehended immediately. This suggests there is a traitor within their underground network, and leaves Lan (Liu) and Zhang (Zhang Yi) to make the treacherous journey alone, while evading Zhou (Yu Hewei) and the rest of Section Chief Gao’s (Ni Dahong) collaborating forces.

“The film’s numerous action sequences are filmed with far more clarity, slickly transitioning from mountainside shoot-out to high-speed car chase, as bullets fly and the unrelenting blizzards add a sprinkle of aesthetic glitter to the shifty cloak-and-dagger escapades, all to the strains of an arresting, Morricone-esque score. However, the endless scenes of torture and interrogation get somewhat repetitive, while a tacked-on subplot involving abandoned street urchins is an unnecessary distraction in an already overstuffed plot. Ultimately, Cliff Walkers sports the flawless disguise of a top-tier spy thriller, but when the screws are tightened simply can’t get its story straight.

Image Sources: Movie posters, IMDB, Wikipedia, Wiki Commons

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated November 2021