WILD YAKS

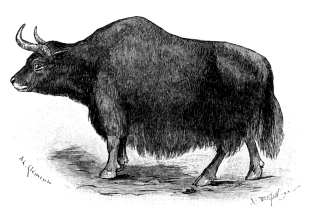

Wild yaks (Bos grunniens) are called drongs in Tibetan. They are up 3.25 meters (10.6 feet) in length and weigh between 305 and 820 kilograms (672 to 1,808 pounds). They live in alpine tundra and cold desert regions at altitudes between 4,000 and 6,000 meters (13,124 and 19,685 feet). They are kept warm by a dense undercoat of soft, close-matted hair covered by generally dark brown to black outer hair. Wild yaks are very rare. Few non-Tibetans and not many Tibetans either have ever seen a wild yak. They live both as solitary individuals and in groups in windy, desolate, extremely cold steppes, mainly in the Kashmir and Leh areas of India and in Tibet and Qinghai in China.

Wild yaks are larger but thinner than domestic yaks. Males can weigh up to 1,000 kilograms and measure 1.8 meters at the shoulder. Wild yaks are mostly black or dark brown, with the exception of the fabled golden wild yak. They generally have long black hair and horns that come out the sides of their head and turn upwards. Drongs In northern Tibet reportedly weigh a ton and reach a length of almost four meters (12 feet) and have a horn span of one meter (three feet). Herds of drongs are docile but an individual drong will sometimes charge.

There are estimated to be around 15,000 wild yaks remaining. On the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List, wild yaks are listed as Vulnerable. On the US Federal List they are classified as Endangered. In CITES (Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild) they are in Appendix I under No special status. They are threatened by habitat loss, poaching, diseases introduced by live stock, interbreeding with domestic yaks, low fertility and inbreeding.

See Separate Article: YAKS: CHARACTERISTICS, USES, BUTTER, MANAGEMENT factsanddetails.com

Yak History

Fossil remains of wild yak ancestor date back to the Pleistocene period (2,6 million to 11,700 years ago). Over the past 10 000 years or so, the yak developed on the Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau, which covers about 2.5 million square kilometers (970,000 square miles). Yaks have been domesticated for centuries. Sometimes they are left on their own in mountain pastures for so long they become semi-wild. [Source: FAO]

Yaks belonging to the genus Bos, which also includes cattle (Bos primigenius). Mitochondrial DNA analyses to determine the evolutionary history of yaks have been inconclusive. They yak may have diverged from cattle at any point between one and five million years ago, and there is some suggestion that it may be more closely related to bison than to the other members of the bos genus. Close fossil relatives of yaks, such as Bos baikalensis, have been found in eastern Russia, suggesting a possible route by which yak-like ancestors of the modern American bison could have entered the Americas. [Source: Wikipedia]

Yaks were originally designated as Bos grunniens ("grunting ox") by Linnaeus in 1766. This name is now generally considered to refer only to domesticated yaks, with Bos mutus ("mute ox") being the preferred name for wild yaks. Although some scientists still consider the wild yak to be a subspecies, Bos grunniens mutus, the ICZN made an official ruling in 2003 allowing the use of the name Bos mutus for wild yaks, and this is now the more common usage. There are no recognised subspecies of yak except where the wild yak is considered a subspecies of Bos grunniens.

The wild yak may have been tamed and domesticated by the ancient Qiang people. Chinese documents from ancient times (eighth century B.C.) testify to a long-established role of the yak in the culture and life of the people. From the south to the north, the distribution of the domestic yak now extends from the southern slopes of the Himalayas to the Altai and west to east from the Pamir to the Minshan mountains. In relatively recent times the area of distribution has further extended to, for example, the Caucasus and North America. In addition, yak are found in zoos and wild animal parks in many countries. [Source: FAO]

Drongs used to roam in the wild in vast herds. In the 1950s, it was estimated that there were around one million of them roaming the Qinghai-Tibetan plateau. Now there are only around 10,000 to 15,000 of them. Their numbers have been reduced mainly by hunters, supplying a demand for yak meat. Wild yaks are about as easy to kill as American buffalo.

Wild Yak Habitat and Where They Are Found

While their domesticated counterparts can be found in a much more varied area in Asia, the main geographic range of wild yaks is limited to the Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau, which includes " the western edge of Gansu Province, Qinghai Province, the southern rim of the Xinjiang Autonomous Region, and the Tibet Autonomous Region." There are few wild yaks living in India and Nepal.

In Tibet, wild yak can be found in the Tangula Mountain Range and along the Tongtianhe River banks. The last herds of the wild yaks live in the remote alpine tundra and ice desert regions of the Tibetan Plateau, mostly in the Chang Tang National Nature Reserve. Here the altitude is 4,000 to 6,000 meters (13,123 to 19,685 feet), and the temperature can fall below-20C. Annual rainfall amounts range from 10 to 30 centimeters (3.9 to 11.8 inches), falling mostly as hail or snow, and leaving little surface water. Grasses and low shrubs make up most of the vegetation.

Wild yaks generally live at elevations of 3200 to 5400 meters (10,500 to 17717 feet) at an average elevation of 4500 meters (14764 feet). Their habitat can vary, but consists mainly of three areas with different vegetation: 1) Alpine meadow, 2) alpine steppe, and 3) desert steppe. Each habitat features large areas of grassland, but have different types of grasses and shrubs as well as differing amounts of vegetation and precipitation and different temperature ranges. [Source: Matthew Oliphant, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

Habitat can define the yaks behavior and habits. Some herds migrate large distances seasonally to feed on grass, moss, and lichens. As a rule, yaks do not like warm weather and, preferr the colder temperatures of the upper plateaus. In recent years, wild yaks has been increasingly confined to desert steppes. This is in part due because these areas are not desirable to farmers thus the wild yaks don’t have to compete with domesticated yaks and livestock.

Wild Yak Characteristics and Diet

Wild yak range in weight from 300 to 1000 kilograms (660 to 2200 pounds). Large males can be up to 3,25 meters (10.6 feet) in length and up to two meters (6.5 feet) in height. Sexual Dimorphism (differences between males and females) is present: Males are larger than females. The average weight for males is 1,000 kilograms with the female being around 300 kilograms. Domestic yaks are considerably smaller in weight, with males ranging from 350 to 580 kilograms (770 to 1,280 pounds) and females between 225 to 255 kilograms (496 and 550 pounds). In the wild, the maximum lifespan of yaks is about 25 years. [Source: Matthew Oliphant, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

Wilk yaks generally have blackish brown fur, large black upward curving horns, and long hair covering the body including the tail. In contrast, domesticated populations have shorter legs, broader hooves, more varied fur coloration, and weaker horns which sometimes can be absent altogether. Both wild and domesticated yaks have large lungs, a high red blood cell count, and higher concentration of hemoglobin than most other bovids — all of which help the yaks thrive in the thin air and cold temperature of their higher elevation habitats.

Yaks are grazers. Their diet is composed mainly of various low-lying grasses and grass-like plants, including shrubs, forbs and cushion plants. They also consume leaves, mosses, other bryophytes and lichens. and crush and crunch ice and snow to obtain water.

Wild Yak Behavior

Wild yaks are motile (move around as opposed to being stationary), nomadic (move from place to place, generally within a well-defined range), social (associates with others of its species; forms social groups), and have dominance hierarchies (ranking systems or pecking orders among members of a long-term social group, where dominance status affects access to resources or mates). [Source: Matthew Oliphant, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

Yaks are most active in the morning and evening and spend most of their time in single-sex herds. They cover great distance as they forage for vegetation, sometimes moving to and from various areas depending on the season. They sense using touch and chemicals usually detected with smell.

Females and males live separately for most of the year. Male bulls band together in groups up to 12 individuals of live alone. Females and young form herds with around 10 to 12 individuals. They are joined by males in the breeding season, which is usually in September. Herds of 200 individuals have been reported. A survey of the Chang Tang Reserve in the 1990s found smaller herds, typically made up two to five individuals for male herds, and six to 20 individuals in mainly female herds.

Wild yaks are much more aggressive than their domesticated cousins and are quick to charge when an intruder appears. In most cases though it prefer to stop short of making contact and risking a confrontation. The only natural predators that wild yaks have to concern themselves are Tibetan wolves taking young. When there are signs of danger, wild herds of yaks generally run from the threat. They may snort loudly and charge at the perceived threat. Sometimes, for unknown reasons, wild yaks kill domesticated yaks.

Wild Yak Mating, Reproduction and Offspring

Wild yaks are polygynous (males have more than one female as a mate at one time) and engage in seasonal breeding. The mating season Yaks starts in September, with births usually occuring in June. The number of offspring is usually one. The average gestation period is 9.3 months. The age in which they are weaned ranges from five to nine months. Females and males reach sexual or reproductive maturity at six to eight years. [Source: Matthew Oliphant, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

For most of the year, male and female wild yaks spend their time in separate herds but they come together during the mating season when males leave their groups and join with the female herds. Males compete for access to receptive females. Violent duels between males sometimes occur.

A single calf is born very other year. Most of the parental care of young is done by females due at least in part to wild female and male yaks to spend the majority of the year in separate groups Young are born able to stand and walk within several hours after birth. Calves remain with their mothers about a year and then often join their group. For the domesticated yak the reproductive cycle is more varied, with the cow sometimes giving birth to more than one calf per year. /=\

Wild Yaks, Humans and Conservation

Humans have traditionally utilized wild yaks for food and fur. Their dung is source of fuel and fertilizer. While there are stiff penalties for hunting wild yak, the practice still takes place, especially in the winter when some local farmers run short of food and kill them for meat. Perhaps one of the largest has been hunting by humans. According to Schaller and Wulin in the 1990s, while the Tibet Forest Bureau is making substantial efforts to protect yak (including fines of up to $600), "Hunting is difficult to suppress without a mobile patrol force, as the recent decimation of wildlife in the Arjin Shan Reserve has shown." [Source: Matthew Oliphant, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

There are several negative economic impacts of wild yaks on humans. Where wild and domesticated Yaks live in close proximity, yak haves sometimes down fences, allowing domesticated yaks. They also sometimes kill domesticated yaks. There is also the possibility of the transmission of disease between domestic and wild yaks.

As pastoralists in Tibet are changing from a nomadic lifestyle to a sedentary one, they are increasing fenced off parcels of land, which interfere with wild yak migrations and access to feeding areas. The introduction of domesticated yaks and other domesticated animals increases the transmission of diseases such as brucellosis and creates competition for the same grazing land

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Animal Diversity Web animaldiversity.org ; National Geographic, Live Science, Natural History magazine, CNTO (China National Tourism Administration) David Attenborough books, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Discover magazine, The New Yorker, Time, BBC, CNN, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Wikipedia, The Guardian, Top Secret Animal Attack Files website and various books and other publications.

Last updated April 2025