BIRDS IN TIBET

In Tibet, there are over 532 different species of birds in 57 families, which is about 70 percent of the total families found in China. They include: storks, wild swans, Blyth's kingfisher, geese, ducks, shorebirds, raptors, brown-chested jungle flycatchers, redstarts, finches, grey-sided thrushes, Przewalski's parrotbills, wagtails, chickadees, large-billed bush warblers, bearded vultures, woodpeckers and nuthatches. The most famous being the black-necked crane called trung trung kaynak in Tibetan. [Source: Chloe Xin, Tibetravel.org tibettravel.org]

Tibet lies along major migration routes for birds. More than 480 species have been sighted in Tibet. Of the these only 30 or so live in Tibet full time. Among the birds seen in Tibet are lammergeyers, partridges, pheasants, grebes and snow cocks. Large flocks of vultures sometimes circle monasteries, waiting for sky burials. Good birdwatching spots include the lakes of Yamdrok-tso and Nam-tso.

The rare black-necked crane inhabits remote regions as high as 16,000 feet. It was is the last of the crane species to be discovered and is revered as a spiritual being by Tibetans. Black-necked cranes breed in the marshy Maquan Valley near Paryang and in Qinghai. They have also spotted on the Lhasa River near Lhasa. See Animals Under Nature

Bar-headed geese summer in the high plateaus of Tibet. During their southward migration they reach heights of 25,000 as they cross the Himalayas, to winter in India.

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Birds of the Himalayas” (Pocket Photo Guides)by Bikram Grewal and Otto Pfister Amazon.com

“Himalayan Wildlife: Habitat and Conservation” by S. S. Negi Amazon.com;

“Stones of Silence” by George Schaller Amazon.com;

“Wild Animals of India, Burma, Malaya and Tibet” by Richard Lydekker Amazon.com ;

“Chinese Wildlife” ( Bradt Travel Wildlife Guides) by Martin Walters Amazon.com

“Wildlife of India” by Bikram Grewal Amazon.com;

“Tibet's Hidden Wilderness: Wildlife and Nomads of the Chang Tang Reserve

by George B. Schaller Amazon.com

“Chang Tang A High and Holy Realm in the World”

by Liu Wulin Amazon.com

“Big Open: On Foot Across Tibert's Chang Tang”

by Rick Ridgeway , Galen Rowell, et al. Amazon.com;

Tibetan Bunting, One of the World's Rarest Birds

Phil McKenna wrote in Smithsonian magazine, “The Tibetan bunting (Emberiza koslowi) is one of the least-known birds on the planet. It has a black and white head and chestnut-colored back and is only slightly larger than a chickadee. In 1900, Russian explorers were the first to document the bird and collect specimens. One hundred years later, British ornithologists published only the third scientific study of the bunting, based on fewer than four hours of observations. [Source: Phil McKenna, Smithsonian magazine, October 2011]

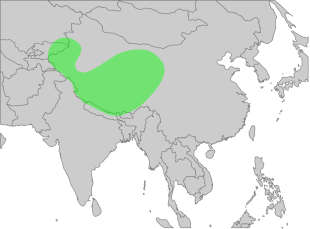

The bird’s obscurity is due in large part to the remoteness of its habitat. In A Field Guide to the Birds of China, the bunting’s home range appears as a tiny splotch on the eastern edge of the Tibetan plateau. The bird lives in a region of rugged peaks and isolated valleys where four of Asia’s largest rivers — the Yellow, the Yangtze, the Mekong and the Salween — tumble down snowcapped mountains before spreading across the continent.

Tibetans call it the “dzi bead bird”because the stripes on its head resemble the agate amulets locals wear to ward off evil spirits. Tashi and his friends have tracked the birds closely for the past eight years. They now know that buntings descend 2,000 feet downslope into warmer, more protected valleys in November and stay there until May. They know how the birds’ diet changes throughout the year: In winter buntings forage on oats and other grains; in summer they eat butterflies, grasshoppers, beetles and other insects. The monks have found that the birds lay an average of 3.6 eggs per nest, and that their main predators are falcons, owls, fox and weasels, in addition to badgers.

For the complete article from which the material here is derived see smithsonianmag.com

Vultures in Tibet

Himalayan vultures (Gyps himalayensis) are large-sized bird of prey that are 1.2 meters long and weigh six to seven kilograms. Their wing wingspan can reach three meters. Their preferred habitats are plateaus, deserts and mountain areas. Also known as Himalayan griffon vulture, they feed mostly on carrion and dead animals of all kinds and use their strong bills to tear meat off the bones. They can be found on the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau and regions nearby. They are regarded as threatened not endangered species.

Himalayan vultures gather in groups. They spend much of their time in the air using thermals to keep them aloft. They swoop down when they smell carrion or discover the corpses of dead animals. When a yak or an ox dies in the open, dozens of Himalayan vultures gather and can eat the entire corpse in a day. Himalayan vultures builds their nests in steep cliffs of high mountains and nest their eggs once a year. They have special resistance to diseases. Yhey often eat the dead bodies of animals that died of diseases but never get sick themselves. In Tibet, the Himalayan vultures that eat the dead corpses of human are regarded as holy birds. It is strictly prohibited to kill such birds in Tibet.

The bearded vulture, Eurasia's biggest raptor, also live in Tibet. They too have traditionally been regarded as a sacred bird in Tibet because it usually does not prey upon living animals, but feeds on dead animals or body. In a Tibetan sky burial, the corpse is offered to these vultures. It is believed that the vultures are Dakinis, the Tibetan equivalent of angels. In Tibetan, Dakini means "sky dancer". It is said Dakinis take the soul into the heavens, which is understood to be a windy place where souls await reincarnation into their next lives. The donation of human flesh to the vultures is considered virtuous because it saves the lives of small animals that the vultures might otherwise capture for food. Sakyamuni, one of the Buddhas, demonstrated this virtue. To save a pigeon, he once fed a hawk with his own flesh. Drigung-til Monastery in Lhasa is famous for its sky burial site and vultures. [Source: Chloe Xin, Tibetravel.org , June 3, 2014 ]

See Vulture, Sacred Bird of Tibet Under Tibetan Sky Burials factsanddetails.com

Himalayan Vultures

Himalayan vultures (Gyps himalayensis) live upland areas of Tibet and of central Asia, ranging from Kazakhstan and Afghanistan in the west to western China and Mongolia in the east. These birds generally only migrate altitudinally within their central Asian range, but some juveniles have been observed in Southeast Asia in northern Myanmar to northwest Indonesia during autumn winter months, from October through March, perhaps because of a lack of food in their native range. [Source: Amrit Gill, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

Himalayan vultures are live at elevations of 600 to 6,000 meters (1,968 to 19,685 feet). Breeding typically occurs at elevations between 600 and 4,500 meters (14,763 feet) . Foraging has been observed at elevations as high as 5,000 meters or more. The landscape of the plateau region where they live is dominated by meadows, especially in the north, and also includes alpine shrub in the middle and forests in the south. Non-breeding migrants such as juveniles tend to spend the boreal winter in the lowland plains near the southern edge of their range, just south of the Himalayas. The lifespan of Himalayan vultures is not known for sure. The the longest recorded lifespan in captivity of one of their closest relatives, White-backed vultures, is around 20 years.

Himalayan vultures are highly respected by Tibetan Buddhists culture on the Tibetan plateau. They play a play a key role in their centuries-old tradition of sky burials. At sky burial sites, human corpses are left for the vultures to consume. On the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List they are listed as Near Threatened. In CITES (Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild) they have no special status. In parts of Asia and Africa, especially India, the use of veterinary diclofenac, a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug, on animals that vultures ulimately feed as carrion has had a devastating impact on Gyps vultures. Diclofenac, causes visceral gout in vultures that have consumed contaminated carcasses ultimately resulting in renal failure. The consumption of carcasses exposed to diclofenac has caused significant declines of the numbers of vultures in India and threaten Himalayan vultures, especially immature Himalayan vultures that winter there.

Apart from humans, there are no known natural predators of Himalayan vultures. Himalayan vultures play an important ecosystem roles of remove and processing carrion. They are most dominant avian scavenger on the Tibetan plateau, with little competition from other scavengers.

Himalayan Vulture Characteristics and Diet

Himalayan vultures are huge, bulky birds with stout bills, loosely feathered ruff, long wings, and a short tail. They range in weight from eight to 12 kilograms (17.6 to 26.4 pounds) and have a head and body length that ranges from 95 to 130 centimeters (37.4 to 51.2 inches). Their wingspan ranges from 2.7 to three meters (8.9 to 9.8 feet). Sexual Dimorphism (differences between males and females) is not present: Both sexes are roughly equal in size and look similar. [Source: Amrit Gill, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

As juveniles become older they experience a gradual change of body covering from white down to dark brown feathers with the head remaining a whitish color. Adults have a strong contrast between cream and black, while the juveniles are dark. The reddish plumage of adults is used to distinguish them from Eurasian griffon vultures, which are darker and smaller. Himalayan vultures are also much larger than Indian vultures (g. indicus) and possess a stouter, more robust bill.

As is the case with other Gyps vultures — which include Eurasian griffon vultures and Indian vultures — Himalayan vultures prefer the carrion of large mammals — both wild and domesticated. Food is located visually while soaring either directly or indirectly by observing of other scavenging birds. Yaks (Bos grunniens) make up the majority of their diet due to the large biomass of a single animal, followed by wild ungulates such as Kiang (Tibetan asses) and Chiru (Tibetan antelope). Himalayan vultures can swallow large chunks of flesh but prefer softer carcass parts.

Himalayan Vultures Behavior and Reproduction

Himalayan vultures are diurnal (active during the daytime), motile (move around as opposed to being stationary), nomadic (move from place to place, generally within a well-defined range) and both solitary and social. They communicate with vision and sound and sense using vision, touch, sound and chemicals usually detected with smell. Like most Old World vultures, Himalayan vultures rely predominantly on their eyesight to find food compared to New World vultures which rely heavily on their keen sense of smells. [Source: Amrit Gill, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

Compared to other Gyps vultures, adult Himalayan vultures are more solitary, usually nesting alone or in small colonies composed of four to six pairs on cliff faces. Their large body size allows them them to get first dibs during feeding at carcasses with other vultures species such as cinereous vultures (Aegypius monachus) and bearded vultures (Gyaetus barbatus). Both of these species are subordinate to the Himalayan vultures and keeping their distance from them when consuming carcasses to avoid aggression by Himalayan vultures, whuch are highly mobile foragers that tend to keep their distance from human settlements.

Himalayan vultures are monogamous (having one mate at a time) are generally site faithful, which means they return to the same nesting and roosting sites every year. They breed once a year, most commonly during the winter from December to March. Only one milky, white egg is laid each season. The time to hatching ranges from 54 to 65 days. Nests are built on ledges or in small caves of cliffs 100 to 200 meters above the ground. Depending on the size and structure of the cliff, nesting colonies can hold between five and sixteen nests. Nests are predominantly composed of sticks and they can be either constructed by the birds themselves or those of bearded vultures that have been taken over and repaired. Nests are typically built or repaired from December to March. Eggs are laid between January and April, with hatching occurring between February and May.

Himalayan vulture chicks generally mate at the nest site, and never on the ground. No courtship display has been observed. The chest patches of females take on a distinct reddish tint prior to mating. If the female is receptive to a male, she crouches down as the male approaches. The male then proceeds to jump onto the female's back and takes hold of her ruff with his beak, all while emitting loud roaring calls until there is contact between the cloacae. The entire sequence can take anywhere from 30 seconds to a few minutes.

Bearded vulture

Himalayan vulture chicks weigh around 164 grams when they hatch covered in white down and fully capable of delivering a nasty bite. They are reared from July to September (sometimes October) at which time the juveniles fledge and leave the nest. The entire four to seven month reproductive period is one of the longest recorded among Gyps vultures. Adult birds have little time to recover before they go through the whole process again. Breeding is not synchronized among pairs, with hatchings occurring at different dates for different pairs over a one or two month period. The fledging age ranges from five to six months.

According to Animal Diversity Web: Males and females both take part in building nests. Before the egg is laid, the female plunges her breast into the nest pushing the material into place to make a depression while the male brings material for the nest to the female. Both sexes participate in incubation, with the female typically on the nest during the morning while the male takes over in the afternoon. Both parents take care of the nestling. After hatching the chick is closely brooded for the first few days, but by the end of the week the parents begin to leave it unattended for extended periods of time. The female alone remains with the chick throughout the entire hatching period and aids in pipping the egg via cracking it by breaking off pieces with the tip of her beak. The chick is slipped out of the shell with the help of the female and the male then consumes the shell. Both sexes are equally involved in feeding the nestling. Initially, the parents regurgitate a thick, whitish fluid from their stomachs that serves as the primary food source for the nestling, but over time they begin to feed it small pieces of carcass. Overall, both males and females exhibit similar parental behaviors consisting of preening the chick, watching it, moving it around, and feeding it.”/=\

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, Cosmic Harmony, Purdue University

Text Sources: Animal Diversity Web animaldiversity.org ; National Geographic, Live Science, Natural History magazine, David Attenborough books, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Discover magazine, The New Yorker, Time, BBC, CNN, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Wikipedia, The Guardian, Top Secret Animal Attack Files website and various books and other publications.

Last updated March 2025