SKY BURIALS

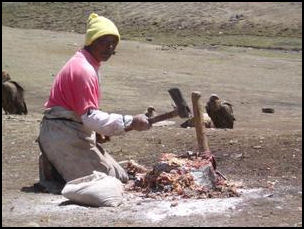

Crushing the bones during a Sky Burial"Sky burials” are the most common way of disposing of dead bodies in Tibet. A sky burial is simply the disposition of a corpse to be devoured by vultures. A monk or sky burial specialist eviscerates the human corpse, leaving the flesh as food for vultures and smashing the bones into a grainy dust. The process is supposed to liberate the spirit from the body for peaceful transport into the next life. In Tibetan Buddhism, it is believed that sky burial represents the wishes of the soul to ascend to the afterlife. It is the most common way for ordinary Tibetans to be taken care after they die. Sky burials also have a practical side. They make sense in a land where fuel is scarce and the earth is often too hard to dig.

During a "sky burial”the body of the deceased is carried to a monastery on the backs of close friends and cut into little pieces by monks or members of a professional caste, and the pieces are fed to vultures who carry the spirit skyward to heaven. Family members of the deceased are often nearby but not actually at the site of the burial. When a body arrives the hair is cut off, the body is cut into pieces and the bones are pulverized and mixed with tsampa for the vultures to eat. Before stripping the flesh off the bones the monk who does the deed usually sharpens his knife on the sides or a rock, walks around a monument and says a prayer.

Groups of cinereous vultures fly to fight and peck the food. It is the luckiest if the corpse is consumed totally by vultures, which means the dead have no sin and the soul has gone up the heaven safely. If there are some remains, they should be picked up and cremated, while lamas chant sutras.

Sky burial are usually performed in places where wood is scarce and the climate is cold. Tibetans can’t bury their dead because the ground is often frozen, nor can they burn them because there is little wood. The bones are collected and taken home and scattered. For important lamas the bones are mixed with mud and made into a chorten.

The Chinese artist Zhang Huan witnessed a sky burial when he visited Tibet in 2005.“Most people, when they see this ceremony, think it is gross and they cannot bear to watch,” he told the New York Times. “But, when I watch the ceremony, I feel this hallucination of happiness, and I feel free.” [Source: Barbara Pollack, New York Times, September 12, 2013]

See Separate Articles: TIBETAN BUDDHISM factsanddetails.com; TIBETAN FUNERALS AND VIEWS ON DEATH factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: “Tibetan Rituals of Death” by Margaret Gouin Amazon.com; “The Tibetan Book of the Dead” by Padmasambhava Amazon.com; “The Tibetan Book of the Dead for Beginners: The Path to Liberation and Spiritual Awakening Made Accessible” by Jamyang Lhamo and Divine Light Publishing Amazon.com; “The Illustrated Tibetan Book of the Dead” by Stephen Hodge and Martin Boord Amazon.com; “The Six Bardos of the Tibetan Book of the Dead: Dzogchen Teachings on the Peaceful and Wrathful Deities” by Ven. Khenchen Palden Sherab Rinpoche, Ven. Khenpo Tsewang Dongyal Rinpoche, et al. Amazon.com; “A Step Away from Paradise: The True Story of a Tibetan Lama's Journey to a Land of Immortality” by Thomas Shor and Tenzin Palmo Amazon.com;“The Unique Customs and Taboos in Tibet and Their Meanings” by Kokshin Tan Amazon.com; Tibetan Buddhism: “Essential Tibetan Buddhism” by Robert A. F. Thurman Amazon.com; “Initiations and Initiates in Tibet” by Alexandra David-Neel Amazon.com; “The Secret Oral Teachings in Tibetan Buddhist Sects” by Alexandra David-Neel, Lama Yongden Amazon.com; Introduction to Tibetan Buddhism by John Powers Amazon.com; “The World of Tibetan Buddhism: An Overview of Its Philosophy and Practice” by His Holiness the Dalai Lama, Geshe Thupten Jinpa Amazon.com; “Tibetan Buddhism: With its Mystic Cults, Symbolism and Mythology, and in Its Relation to Indian Buddhism” by L Austine Waddell Amazon.com; “The Preliminary Practices of Tibetan Buddhism” by Geshe Rapten Amazon.com; “Teachings and Practice of Tibetan Tantra” Amazon.com; “Tantra in Practice” by David Gordon White Amazon.com

Chinese Government View on Sky Burial

Adding flour

Communists officials banned sky burials in the 1960s and 70s. As part of tolerance for Tibetan customs and religious practices, sky burials were allowed again in the 1980s. The vice governor of Tibet told the New York Times in 1999, "We encourage cremation but we allow sky burial. It’s a Tibetan custom...Tibetans feel very strongly about sky burial. A few years ago, a Chinese soldier shot a vulture and was stoned by Tibetans. It was understandable. if vultures are fair game, who us going to do sky burial."

According to the Chinese government: “Celestial burial is comparatively widespread burial custom among Tibetan, and it is also called "bird burial". People who believe in religion hold the idea that the celestial burial is placed with their dream of going up to "heaven". Tibetans think that the cinereous vultures in the mountains around the celestial platform are "magical birds": they only eat human corpses and don't hurt any small animals. This kind of burial is influenced by the spirit of "sacrificing oneself to feed the tiger" in biography of Sakyamuni, so it is still very popular now. [Source: Liu Jun, Museum of Nationalities, Central University for Nationalities, kepu.net.cn ~

Sky Burial Customs and Taboos

In Lhasa sky burials are performed at dawn at special burial grounds, near a temple, that have been used for such burials for centuries. The rituals are closed to outsiders. In remote areas of Tibet the burials can sometimes be observed by outsiders. Participants of funerals regard ogling tourists as invasions of their privacy. Taking photographs is considered to be horrible manners.

On the day before the burial, the family members take off the clothes of the dead and fix the corpse in a fetal position. At dawn on the lucky day, the corpse is sent to the burial site among mountains which is always far from the residential area. Then "Su” smoke is burned to attract condors, Lamas chant sutras to redeem the sins of the soul, and a professional celestial burial master deals with the body. If the vultures come and eat the body, it means that the dead has no sin and that his/her soul has gone peacefully to the Paradise for Tibetans believe that the condors on the mountains around the celestial burial platform are "holy birds" and only eat the human body without attacking any small animals nearby. Any remains left by the holy birds must be collected up and burnt while the Lamas chant sutras to redeem the sins of the dead, because the remains would tie the spirits to this life. [Source: Chloe Xin, Tibetravel.org]

There are a lot of taboos associated with sky burials. Strangers are not allowed to attend the ceremony as Tibetans believe it could negate the efforts of the ascending souls. So visitors should respect this custom and keep away from such occasions. Family members are also not allowed to be present at the burial site. Despite all this, sky burials intrigue the morbid curiosity of many people. If you have an opportunity to witness a sky burial in Tibet, please respect local custom. Do not get close to the sky burial site and do not take photos, talk or ask any questions on site. Just stay quiet.

Preparation for a Sky Burial

Collecting all the pieces

Pamela Logan wrote: “Tibetans believe that, more important than the body, is the spirit of the deceased. Following death, the body should not be touched for three days, except possibly at the crown of the head, through which the consciousness, or namshe, exits. Lamas guide the spirit in a series of prayers that last for seven weeks, as the person makes their way through the bardo — intermediate states that precede rebirth. [Source: Pamela Logan, “Witness to a Tibetan Sky-Burial, A Field Report for the China Exploration and Research Society, Drigung, Tibet; September 26, 1997, alumnus.caltech.edu /+/]

When a Tibetan dies, the corpse is wrapped in white Tibetan cloth and first placed in a corner of a room on sun-dried mud brick instead of a bed. Tibetan Buddhism expounds that the soul of the dead sometimes refuses to leave the house, although the body is removed. So if its body is placed on the mud brick, the soul will leave, since the brick will be taken out of the house to a road intersection. A man is often consulted to divine the specific date for the funeral.

The deceased is kept in the corner of the house for three or five days, during which monks or lamas are asked to read the scripture aloud so that the souls can be released from purgatory. Once relatives, friends, and neighbors of the dead receive the sad news, each family will send one person with a jar of wine, a hada, and some ghee (pure, liquid butter) to express condolences. Lamas chant sutras and perform Buddhist rituals to expiate the sins of the dead. If the family is rich, they will light 100 lamps for the dead. Otherwise, family members stop other activities in order to create a peaceful environment to allow convenient passage for ascension of souls into heaven. The Family members choose a lucky day and ask the body carrier to carry the body away to the celestial burial platform. [Source: Chloe Xin, Tibetravel.org]

A red pottery vat, whose mouth is covered with wool or a white hada, usually hangs at the gate of the deceased house. Inside are blood, meat, fat, milk, cheese, and butter. With each passing day, more of these items are added, which are meant for the enjoyment of the dead. If a family loses a member, the other members will not comb their hair, clean their faces, wear ornaments, or sing and dance for 49 days. During the funeral arrangements, the family members and their neighbors are not allowed to hold a wedding, sing, or dance. Everyone mourns the loss of the dead.

Day of the Sky Burial

On the day before the burial, people offer their condolences and say farewell to the dead, bringing with them garmai zumda, which includes a hada, Tibetan joss sticks (similar to incense sticks), a sacrificial lamp, and money. Besides the above-mentioned articles, relatives, friends and neighbors also bring zanba (roasted barley flower), milk dregs, tea, and ox lard to boil toba (a type of congee). [Source: chinaculture.org, Chinadaily.com.cn, Ministry of Culture, P.R.China]

The burial takes place early in the morning. The body of the dead is rolled and bent with the head to the knees to make a sitting posture. It is wrapped with a white Tibetan quilt and put on an earth platform, which is on the right side behind the door, A lama chants soul-redeeming classics. The corpse-carrying man carries the body to the celestial burial platform in a luck day. [Source: Liu Jun, Museum of Nationalities, Central University for Nationalities, kepu.net.cn ~

Led by a lama, the descendants of the deceased carry the dead to the door, and relatives, friends, and neighbors, holding Tibetan joss sticks, see the dead off to a fork in the road a distance from the house. Finally, one or two friends accompany the dead to the graveyard and supervise the whole process of the sky burial presided over by a sky burial master. Family members usually are not present at the scene.

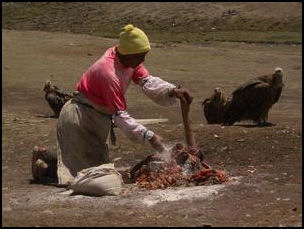

"Sang" (incense) smoke is first lit up to attract cinereous vultures, and the master of celestial burial dismemberments the corpse after the Lama finishes chanting. If the dead is a monk, a design with religious meaning should firstly be carved at the back of the dead. Then the master takes out the internal organs and throws them around. He smashes the bones and skull, and mixes them with Zanba.

Description of a Sky Burial

Describing a sky burial held around noon near a Buddhist temple in the remote town of Lirong, in a Tibetan area in Sichuan, Seth Faison wrote in the New York Times, "The body of a 67-year-old woman was stiff after three days of transport from her home more than 200 miles away...Lobsang, the monk who performed this sky burial, tied a burlap bag around his waist like an apron. Working methodically, with the dispatch of a professional, he stripped the flesh from each of the woman's limbs." [Source: Seth Faison, New York Times, July 6, 1999]

"He took one bone after another, placing them on a flat stone. Raising a small sledgehammer over his head, he smashed them into small pieces...so small they could be devoured by vultures...separating the yield into two small piles, flesh and bone...next to last came her skull, which burst into pieces with a sharp crack, when the hammer came down."

"When Lobsang finished cutting the body, he looked up at the vultures on the hillside. He signaled them, with a flick of the wrist, that it was feeding time. On cue the birds descended in a mass of flapping wings and pecking beaks, devouring the remains in minutes...No trace of the woman's body remained...The vultures, about of 50 of them, ambled slowly up the hill and took to the air with evident difficulty, overfed as they are from the daily ritual." Lobsang told the New York Times he disposed of 10 to 15 bodies a week and was paid about $5 for each one. "I come here every day, and its about the same. Some bodies smell worse. Some are bigger, heavier. No big deal."

Witnessing a Sky Burial in Tibet

Vultures arrive

Pamela Logan wrote in “Witness to a Tibetan Sky-Burial”: “On the steps in front of Drigung Monastery, a dozen monks chant. Before them on the courtyard flagstones lies a body, wrapped in white cloth, which was carried in on a stretcher an hour ago. The monks are praying for a spirit that was once present here, but now is emancipated from its former home. It is the third such visitor today, for Drigung Gonpa has a profitable but gruesome specialty: disposal of the dead. [Source: Pamela Logan, “Witness to a Tibetan Sky-Burial, A Field Report for the China Exploration and Research Society, Drigung, Tibet; September 26, 1997, alumnus.caltech.edu /+/]

“My team and I arrived here last night, after a long day's drive from Lhasa to Meldor Gungkar County in Central Tibet. Drigung monastery is on a steep hill, overlooking our camp. Above the religious complex is a site for "sky burial," a term meaning disposal of a corpse by allowing it to be devoured by birds. The birds, which are summoned by incense and revered by Tibetans, cast their droppings on the high peaks. Sky-burial is practiced all over the plateau, but Drigung is one of the three most famous and auspicious sites. For me, this is an extraordinary opportunity, for these days not one visitor in five hundred is privileged to witness the ceremony I'm about to see. But I am apprehensive, too, wondering how I will stomach the sight of death. /+/

“After the chanting is over, we walk up a well-trodden path to a high ridge, keeping a respectful distance behind the funeral party, which has come all the way from Lhasa to discharge this final duty to their departed friend. The charnel ground, or durtro, consists of a large fenced meadow with a couple of temples and a large stone circle of stones at one end where the ceremony takes place. Prayer flags hang from numerous chortens, and scent of smoldering juniper purifies the air. Vultures circle overhead, and many more are clustered on the grass, a few meters from the funeral bier. /+/

“Men in long white aprons come out, and unwrap the corpse, which is naked, stiff, and swollen. The men hold huge cleavers, which are in a few strokes whetted to razor sharpness on nearby rocks. The bright sun and clear blue sky diffuse somewhat my ominous feeling. The coroners themselves, are not heavy or ceremonial, but completely businesslike as they chat amongst themselves, and prepare to start. /+/

“As the first cut is made, the vultures crowd closer; but three men with long sticks wave them away. Within a few minutes the dead man's organs are removed and set aside for later, separate disposal. The vultures try to move in and are prevented by waving sticks and shouts. Then, the cutters give a signal and the men all simultaneously fall back. The flock rushes in, covering the body completely, their heads disappearing as they bend down to tear away bits of flesh. They are enormous birds, with wings spanning more than 2 meters, top-feathers of dirty white, and huge gray-brown backs. Their heads are virtually featherless, so as not to impede the bird when reaching into a body to feed. /+/

“For thirteen minutes the vultures are in a feeding frenzy. The only sound is tearing flesh and chittering as they compete for the best bits. The birds are gradually sated, and some take to the air, their huge wings sounding like steam locomotives as they flap overhead. Now the men pull out what remains of the corpse — only a bloody skeleton — and shoo away the remaining birds. They take out huge mallets, and set to work pounding the bones. The men talk while they work, even laughing sometimes, for according to Tibetan belief the mortal remains are merely an empty vessel. The dead man's spirit is gone, its fate to be decided by karma accumulated through all past lives.” /+/

“The bones are soon reduced to splinters, mixed with barley flour and then thrown to crows and hawks, who have been waiting their turn. Remaining vultures grab slabs of softened gristle and greedily devour them. Half an hour later, the body has completely disappeared. The men leave also, their day's work finished. Soon, the hilltop is restored to serenity. I think of the man whose flesh is now soaring over the mountains, and decide that, if I happen to die on the high plateau, I wouldn't mind following him.” /+/

Environmental and Spiritual Aspects of Sky Burials

Vultures fight over pieces

A monk who observes sky burials told the New York Times, "When the body dies, the spirits leaves, so there is no need to keep the body. The birds, they think they are just eating. Actually they are removing the body and completing parts of life's cycle.”

Environmentalists say that sky burials are good for the environment because no wood is burned, no water is fouled and no space is used up. A British writer pointed out, "What better way for the body to be returned to earth than directly as vulture droppings?"

Sometimes the bodies are eaten by wild dogs rather than vultures. In a National Geographic article, Chinese scholar Wong How-Man described a monk who couldn't get vultures to come to his "sky burials" so he hired a man who knew how to attract the birds with a special whistle.

Vultures have been driven away from sky burial sites in Lhasa by all the development.

Vulture, Sacred Bird of Tibet

The bearded vulture, Eurasia's biggest raptor, has traditionally been regarded as a sacred bird in Tibet because it usually does not prey upon living animals, but feeds on dead animals or body. sacred vulture in tibet. In a Tibetan sky burial, the corpse is offered to these vultures. It is believed that the vultures are Dakinis, the Tibetan equivalent of angels. In Tibetan, Dakini means "sky dancer". It is said Dakinis take the soul into the heavens, which is understood to be a windy place where souls await reincarnation into their next lives. [Source: Chloe Xin, Tibetravel.org]

The donation of human flesh to the vultures is considered virtuous because it saves the lives of small animals that the vultures might otherwise capture for food. Sakyamuni, one of the Buddhas, demonstrated this virtue. To save a pigeon, he once fed a hawk with his own flesh. Drigung-til Monastery in Lhasa is famous for its sky burial site and vultures.

Vultures in Tibet are also respected as nature’s sweeper and protector. Every year, countless animals are killed by Tibet’s harsh climate and lay on the snow, where they can potentially contaminate the water supply. The Himalayas and Tibet are the water sources of the rivers throughout the South and East Asia, like Yellow River and Yangtze River of China, the Ganges River of India. These rivers are Asian’s main drinking water source. Vultures do their part to keep human and animal remains from polluting drinking water sources. Wish humans could do their part better.

Tibetan Buddhists believe that vultures carry the soul of a dead person to heaven. If vultures do not visit the corpse it is believed that the individual has sinned greatly during his or her lifetime. [Source: Amrit Gill, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

See Vultures in Tibet Under ANIMALS IN TIBET factsanddetails.com

Image Sources: O Rotem, Global Hopkins

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated April 2025