TIBETAN FAMILIES

The Tibetan families tend to be male-centered and patriarchal. Men inherit property. Women are expected to obey her husband, even when he lives with her parents. Today, most Tibetans live in monogamous families although polyandry (a woman married to multiple men) exists. The most important functioning kin group is the extended family, which often live together in a single household. Family names, which are carried by the males of some families, reflect the patrilineal inheritance pattern and are also used to demarcate the noble families. |~|[Source: Rebecca R. French, e Human Relations Area Files (eHRAF) World Cultures, Yale University]

Inheritance was traditionally handed to the oldest males but often property was given away as a gift to members of both sexes. Monks and nuns did not inherit. According to the “Encyclopedia of World Cultures”: “Although the traditional inheritance pattern for peasant land was patrilineal descent and primogeniture, both males and females could inherit land or receive it as a gift. Maintenance of the household as the landholding, tax-paying unit could be accomplished by any member of the family. Personal property could also be inherited by any member of the family, although women commonly passed on to their daughters their jewelry, clothing, and other personal possessions. Wills, oral or written, could alter the inheritance pattern. [Source: Rebecca R. French, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 6: Russia — Eurasia / China” edited by Paul Friedrich and Norma Diamond, 1994 ]

The kinship terminology system, which distinguishes between patri- and matrilaterals at the second ascending generation, results in a strong bias toward distinguishing between one's matrilateral and one's patrilateral kin for the purposes of inheritance. For relatives of his or her own level, including cousins, the average Tibetan simply uses the terms “brother” and “sister.” There is local and regional variation in terminology throughout Tibet.

See Separate Articles: MARRIAGE, WEDDINGS AND DATING IN TIBET factsanddetails.com; POLYANDRY (MARRIAGE TO MULTIPLE HUSBANDS) IN TIBET factsanddetails.com; TIBETAN ETIQUETTE AND CUSTOMS factsanddetails.com; many articles TIBETAN LIFE factsanddetails.com ; TIBETAN PEOPLE factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:“The Tibetan Art of Parenting: From Before Conception Through Early Childhood” by Anne Maiden Brown , Edie Farwell, et al. Amazon.com; “Women in Tibet: Past and Present” by Janet Gyatso and Hanna Havnevik Amazon.com; Marriage: “Life and Marriage in Skya rgya, a Tibetan Village” by Blo Brtan Rdo Rje and Charles Kevin Stuart Amazon.com; “Tibetan Weddings in Ne'u na Village”by Tshe Dbang Rdo Rje and Kevin Stuart Amazon.com; “Dragon Thunder: My Life with Chögyam Trungpa” by Diana J. Mukpo and Carolyn Gimian Amazon.com; “The Return of Polyandry: Kinship and Marriage in Central Tibet” by Heidi E. Fjeld Amazon.com; “The Other Side Of Polyandry: Property, Stratification, And Nonmarriage In The Nepal Himalayas” by Sidney Ruth Schuler Amazon.com; Tibetan Life and Customs: “A Hundred Customs and Traditions of Tibetan People” by Sagong Wangdu and Tenzin Tsepak Amazon.com; Magic and Mystery in Tibet: Discovering the Spiritual Beliefs, Traditions and Customs of the Tibetan Buddhist Lamas” by Alexandra David-Neel and A. D'Arsonval (1931) Amazon.com;“Tibetan Life And Culture” by Eleanor Olson Amazon.com; “Tibetan Buddhist Life” by Don Farber and The Tibet Fund Amazon.com

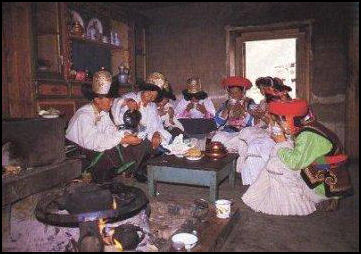

Typical Tibetan Family

Peasant households are typically made of three generations of males and their wives and their children. Members of both sexes rotate in and out of the household with some flexibility. These members can be cousins, uncles, aunts, friends. Men have traditionally done heavy work and work outside the home and women have been in charge of household duties, cooking and child rearing. However, members of both sexes often do chores associated with the other sex and sex roles are often reversed. In Bhutan, for example, unmarried men often give up marriage to help their sisters take care of the children.

A typical family of 14 in Bhutan is made up of a mother and father in their late forties and early fifties (looking older than their age), their one son and three daughters, the oldest daughter's husband and their five children, the mother brother and the father's cousin (a visiting monk).

The mother and father spend much of their day with their animals. The mother milks them, collecting the milk in wooden buckets in the morning and the father uses the larger animals such as cattle and horses to plow the fields.

Women in Tibet

The Dalai Lama paved the way for women for receive advanced degrees but in many ways Tibetan is still a very male-dominated patriarchal society. Today, young boys and girls mingle freely but still have some traditional restrictions.

“Oral Histories of Tibetan Women: Whispers From the Roof of the World “(Oxford and New York, Routledge, 2022) by Lily Xiao Hong Lee is part of the Routledge Research in Gender and History series. According to the publisher: Through the translated stories of twenty Tibetan women of various backgrounds, ages and occupations who were alive in the twentieth century, this book presents broad, under-explored and engaging perspectives on Tibetan culture and politics, ethnicity or mixed ethnicity, art, marriage, religion, education and values.

Offering a unique spectrum of primary sources, this book showcases interviews which were recorded in the 1990s and early 2000s which faithfully document Tibetan women telling their stories in their own words and situate these stories in their historical and socio-cultural contexts. These women were historically and religiously significant, such as a tulku (an incarnate), and tribal and local leaders, as well as ordinary women, such as poor peasants, the urban poor and women in polyandrous marriages.

Children in Tibet

Children have traditionally been encouraged to take up the same occupations as their parents. Young children are doted upon but older children are ideally raised under strict discipline and religious instruction. Instead of wearing diapers many young Tibetan children wear trousers with a big hole cut in seat as is the case with Chinese. In Lhasa, teenagers use cell phones and surf the Internet on Internet cafes. Young adults drink beer and hang out at clubs.

Parents have traditionally exerted a lot of control over their children. One women, who was unmarried at the advanced age of 31, told her widowed father that she wanted to get married but he asked her to remain home and her husband declined to join her fathers camp.

Children Customs in Tibet

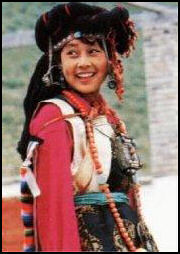

Tibetan girl

After a woman has given birth, people burn yak dung in front of gate to inform they are not supposed to enter and to get rid of the polluting atmosphere produced by procreation. Then people pile up a scree pile. If a boy is born, people pile up more chalk scree. If a girl is born, people use other kind of scree and light Wei-Song nearby.

Three or four days after a baby is born, a tiny piece of tsamba (roasted barely flour, the main Tibetan food) is placed on the infant's forehead. This is a rite to make the baby pure. The newborn baby is not given a name until the end of the birth rituals. Generally, a lama or a prestigious senior villager is invited to name the baby, but there are also cases when the baby is named by his or her parents. No matter who names the baby, the naming is performed in accordance with the will of the baby's parents for auspiciousness. The name usually comes from Buddhist scriptures and often includes some words symbolizing happiness or luck.

When the baby is one month old, a ritual is held on an auspicious day to take the baby out of the home. Before leaving, black ash taken from the pot bottom is used to blacken the baby's nose to ward off evil. Putting black on the baby's nose means that demons will find the baby when he or she goes out and they can be dispelled. Generally, the baby, donned in new clothes, is taken to the monastery for prayers before Buddha and also for blessing. This done to keep away ghosts. With relatives, the child's parents go to the monastery and pray to the Buddha for protection and for a long life for the baby. They may also ask for blessing from a lama. Then they visit the relatives. Sometimes they select some lucky family to visit so the family can pray that the baby will have a happy family in the future.

Tibetan Birth Ceremony

The Tibetan birth ceremony is called Pang-sai in the Tibetan language. The Pang-sai is actually a cleansing ritual aimed at cleansing the child for the journey into this life. "Pans" means “fowls” and "sai" means “cleaning away” in Tibetan. The Tibetans believe newborn babies come to the world alongside fowls, and a ceremony is needed to get rid of the fowls so they the baby can grow up strong and healthy and the mother can recover soon. [Source: Chloe Xin, Tibetravel.org; chinaculture.org,]

Tibetan birth rituals evolved from a Bon religious rituals to worship God, and have been going on for more than 1,500 years. When a baby is born, two banners are placed on the roof eaves and hang down from the edge. One wards off evil to protect the child and the other attracts good fortune. In the morning, the people pick some white small stones and pile them in front of the house of the family where a child is born to show a boy was born; when a girl is born, the people can pick any kind of stones to pile in the front of the house. At the same time, the people burn pine branches. Before entering the house to show congratulations, guests sprinkle tsampa usually mixed with tea on the stone piles before entering the host house.

The actual birth celebration takes place on the third day of the child’s life, for a boy, and fourth day for a girl child. This custom probably dates to old times when children often did not survive birth surviving for three or four days was viewed as a sign they would probably live normally. People may journey from other places to take part in the birth ceremony. They bring gifts of food and clothing. Buttered tea, barley wine, meat, butter and cheese are presented to represent wishes for an abundant life. New clothing and wonderfully colored scarves are presented to represent shelter for life. Scarves are also presented to the parents to convey good wishes. As soon as they enter the house, guests present hada scarves to the baby's parents and then the baby. This is followed by toasting, presenting gifts, and examining the baby while offering good wishes. Some families throw in a pancake feast to entertain the visitors.

A visit by a monk from a local monastery or one’s family is aimed at insuring that the child will develop wisdom. The monk(s) brings religious banners and lead some worship rituals in which everyone participates. Every day for a week, is family and visitors celebrate until the naming ceremony, but nobody comes into the house or sees the child, except immediate family and the monks. Everybody else people are served tea and celebrate in the courtyard, which is usually partly covered and has a warm fire. A month passes before anyone outside of the family or the monks touches the child.

Tibetan Adult Coming-of-Age Ceremony for Girls

Traditionally, a girls' hair was combed into two braids when they are under twelve years of age. They wore three braids when they were thirteen or fourteen, and five braids at the age of fifteen or sixteen. When a girl reaches seventeen, her hair is combed into dozens of braids to show that she is an adult.

In some parts of Tibet, a girl is considered to have come of age when she reaches 17. Traditionally, her parents have marked the event with a ritual that takes place on the second day of the New Year according to the Tibetan calendar or on a auspicious day around the time of her 17th birthday. Parents prepare beautiful clothes and all kinds of ornaments for the occasion. An woman who is an expert in such thing is invited to do the girl's makeup and hair. When the coming of age ritual is performed, her relatives and friends congratulate the girl and some giver her presents. [Source: Chinatravel.com]

The Tibetan coming-of-age ritual is called “Dai Tou”. "Dai Tou" is a common expression for getting married. However, during this ceremony, she is not married to a man but rather to the sky. Because the girl is married to the blue sky, this ceremony is also called "Dai Tian Tou" ("wearing the head of the sky"). The ceremony shows that a young Tibetan women has entered adulthood. [Source: Chloe Xin, Tibetravel.org]

In rural areas, small girls typically sport two pigtails. When they reach the age of 13 or 14 they often have three pigtails and four at the age of 15. When a girl is 17 years old, she may have several dozens pigtails, symbolizing her adulthood. Young men are allowed to court a girl with many pigtails. During the coming of age ceremony, the young girl’s parents and perhaps other relatives and some friends too tie her hair into dozens of braids, which means that she is old enough to get married. Then the girl dons a Patsu decoration and the colorful skirt Bangdian apron. Later, the girl's parents, relatives and guests present her with hadas (traditional white scarves) as congratulation. When the ceremony is over, the girl, followed by three or four relatives, goes to a temple to pray before a Buddha statue. When they come back, the girl’s family hosts a big dinner for the guests.

After this ceremony, girls can identify themselves as adults can have social contacts as such with people. They are also technically allowed to love relationship and bring their boyfriends home. To have a child is acceptable for an adult women in the community. Women after the ceremony a girl can either get married or stay at her parents' home—forever if she likes. Women can ask their lovers to become sexual partners. Unmarried women can live with their sons and daughters and form a matriarchal family.

Young Tibetans

Many young, rural Tibetans are anxious to leave their villages and strike out on their own in the towns and cities and get jobs and try to get ahead. One 19-year-old young women, who works at a hotel about two hours by bus from her village and makes more money than the four farmers in her family put together, told the Washington Post, “I’ve lived here long enough. I want to see other places and do other things. Here, nothing changes.”

The 19-year earns $200 a month plus room and broad working at a trendy guesthouse. She prefers to use a Chinese name rather than a Tibetan one, eschews traditional Tibetan clothes, wears her hair in a bob and always has her cell phone handy. That doesn’t mean she has forsaken her culture. She visits a Buddhist temple four times a week, loves to sing Tibetan songs and says her dream is to go on a pilgrimage to Lhasa. Most of the money she makes she gives to her family.

In Lhasa, Tibetan youth sing in nightclubs and while away the hours playing video games in Internet cafes.

Rough Childhood in Tibet in the 1950s

In a review of “My Tibetan Childhood: When Ice Shattered Stone” by Naktsang Nulo, Kevin Carrico wrote: We see Nukho playing with friends, raising a pet pika with his brother, and encountering mad dogs and horse thieves. Everyday life in Tibet in the 1950s is brought to life vividly in these brief vignettes, a rare accomplishment...““Born on the Wide Tibetan Grasslands” takes readers back to 1949 to witness the birth of the author in Eastern Tibet. The author’s Naktsang family is described as prosperous and flourishing, while their home village of Madey Chaguma in Amdo is described as a vibrant grassland adjacent to the Machu River. Born on a stormy night, baby Nukho’s family finds that he simply will not stop crying, which they perceive as a portent of a sad and difficult life. Indeed, the family’s fortune changes quickly and radically. Nukho’s mother dies when he is only a few years old, ushering in a series of calamities that befall the family: their horses are stolen; they encounter unforgiving robbers; and Nukho’s grandfather and uncle die, leaving only Nukho, his father, and his brother Japey. His father roams to earn a living, while the two boys are supported by the local monastery.

“In the following two sections, entitled “A Childhood with Herdsmen, Bandits, and Monks” and “By Yak Caravan to the Holy City of Lhasa,” readers witness Nukho’s daily life in eastern Tibet in the 1950s, while also joining him and his family on a pilgrimage to Lhasa. Readers “follow Nukho on a pilgrimage with his father and brother to Lhasa at the age of six to commemorate those in his family who had died in the previous years. The journey from Amdo to Lhasa, which the narrator describes as “a very strange, frightening, difficult journey”, is rich with suspense and lively details: the countryside is full of bandits, unpredictable weather, and wild animals.

In one section of this chapter, the group meets a mother bear with her cub, only to discover that the intimidating bear is in fact blind: leaving some cheese behind for her and her cub, the narrator realizes that, despite the donation, they will inevitably die. In another section, they encounter a mother who fought to the death to protect her one-year-old baby from a pack of voracious wolves: the baby is rescued and taken to a monastery to be raised, to the relief of the mother, as she breathes her last dying breaths. After this long journey, arriving in Lhasa, the family visits one monastery a day, has an audience with the Dalai Lama, and celebrates Losar (Tibetan new year) in this historic city.

Book: “My Tibetan Childhood: When Ice Shattered Stone” by Naktsang Nulo, translated by Angus Cargill and Sonam Lhamo (Duke University Press, 2014)

Image Sources: Purdue University, China National Tourist Office, Nolls China website http://www.paulnoll.com/China/index.html, Johomap, Tibetan Government in Exile

Text Sources: 1) “Encyclopedia of World Cultures: Russia and Eurasia/ China”, edited by Paul Friedrich and Norma Diamond (C.K.Hall & Company, 1994); 2) Liu Jun, Museum of Nationalities, Central University for Nationalities, Science of China, China virtual museums, Computer Network Information Center of Chinese Academy of Sciences, kepu.net.cn ~; 3) Ethnic China ethnic-china.com *\; 4) Chinatravel.com \=/; 5) China.org, the Chinese government news site china.org | New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, Lonely Planet Guides, Library of Congress, Chinese government, Compton’s Encyclopedia, The Guardian, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, AFP, Wall Street Journal, The Atlantic Monthly, The Economist, Foreign Policy, Wikipedia, BBC, CNN, and various books, websites and other publications.

Last updated September 2022