TIBETAN BUDDHIST SACRED OBJECTS

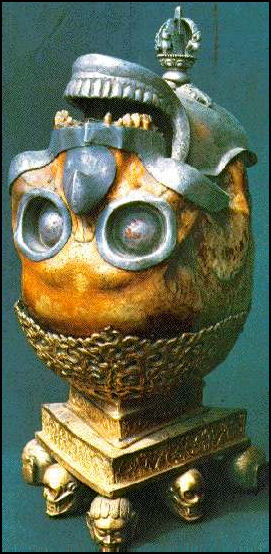

Skull Queen of Heaven Ritual objects play an important role in Tibetan Buddhism. Tibetan Buddhists believe that the power of Buddha can be experienced through statues and other images of Buddha.Some of the main objects in Tibetan Buddhism include the wheel of law (representing the law of the Buddha set in motion); the mandala (symbolizing a miniature cosmos and the platform on which the Buddha addresses his followers); the prayer wheel (inscribed with mani prayers and containing a sutra scroll attached to the axel); and the bumpa vase (containing grass roots symbolizing longevity and peacock feathers symbolizing purity).

Buddhist ceremonial objects are regarded as dignified and solemn and the craftsmen who produce them regard their work as a way of earning merit for their next life. The objects are often adorned with gold, silver, gems and semi-precious stones.

Singing bowls are made from a secret blend of seven different metals. Intended as meditation devices, they produce a chant-like humming noise when a stick is rotated around the outer edge. The devices have their origin in Buddhist bon practices.

Pronged scepters attract spiritual energy like lightning rods; bells are intended to wake up the mind. A “tsatsa” is a small icon made from clay selected at sacred sites. A spirit trap is a series of interlocking threads often places on a tree. They are supposed to catch evil spirits and are burnt after their mission has been accomplished.

See Separate Articles: TIBETAN BUDDHISM factsanddetails.com; TIBETAN BUDDHIST RITUALS, CUSTOMS AND PRAYERS factsanddetails.com; TIBETAN BUDDHIST PRAYER FLAGS AND WIND HORSES factsanddetails.com; TIBETAN ART factsanddetails.com;

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: Buddhist Ritual Art of Tibet: A Handbook on Ceremonial Objects and Ritual Furnishings in the Tibetan Temple Amazon.com; Magic and Mystery in Tibet: Discovering the Spiritual Beliefs, Traditions and Customs of the Tibetan Buddhist Lamas - An Autobiography” by Alexandra David-Neel and A. D'Arsonval (1931) Amazon.com; “Tibetan Ritual” by Jose Ignacio Cabezon Amazon.com; “Tibetan Rituals of Death” by Margaret Gouin Amazon.com; “The Little Book of Tibetan Rites and Rituals: Simple Practices for Rejuvenating the Mind, Body, and Spirit” by Judy Tsuei Amazon.com; Tibetan Buddhism: “Essential Tibetan Buddhism” by Robert A. F. Thurman Amazon.com; “Initiations and Initiates in Tibet” by Alexandra David-Neel Amazon.com; “The Secret Oral Teachings in Tibetan Buddhist Sects” by Alexandra David-Neel, Lama Yongden Amazon.com; Introduction to Tibetan Buddhism by John Powers Amazon.com; “The World of Tibetan Buddhism: An Overview of Its Philosophy and Practice” by His Holiness the Dalai Lama, Geshe Thupten Jinpa Amazon.com; “Tibetan Buddhism: With its Mystic Cults, Symbolism and Mythology, and in Its Relation to Indian Buddhism” by L Austine Waddell Amazon.com; “The Jewel Tree of Tibet: The Enlightenment of Tibetan Buddhism” by Robert Thurman and Sounds True Amazon.com; “A Concise Introduction to Tibetan Buddhism” by John Powers Amazon.com; “The Preliminary Practices of Tibetan Buddhism” by Geshe Rapten Amazon.com; “Teachings and Practice of Tibetan Tantra” Amazon.com; “Tantra in Practice” by David Gordon White Amazon.com

Making Imperial Tibetan Buddhist Ceremonial Objects

According to the National Palace Museum, Taipei: “ In the production of icons” for the Qing Dynasty, “Tibetan Buddhism maintained strict iconographic rules and canons of proportion, as well as fixed regulations for the supply of ritual utensils.However, the Tibetans often recruited artisans from Nepal or the Chinese central plain to make ritual implements. The Qing Imperial workshops involved in the creation of Buddhist ritual implements also brought together Tibetan, Mongolian, and Han Chinese artisans. In addition, the Emperor and certain officials had the power to revise the design and production process. The frequent bestowal and presentation of cultural artifacts at the Qing court added even more impetus to this mutual borrowing of artisans and craftsmanship, along with forms and styles, variously between Han China, Manchuria, Mongolia, and Tibet. The focus of this exhibition of Lamaist cultural artifacts is, then, the stylistically complex ritual objects that emerged from this blending of many different ethnic crafts. [Source: National Palace Museum, Taipei npm.gov.tw ]

“Buddhist objects for ceremonial use were meant to be dignified and solemn. In fact, the artisans themselves regarded their efforts in the creation of ritual objects as a form of Buddhist practice. Amongst the selections on view, we can see the technical mastery of the Mongolian and Tibetan artisans in metal-casting, hammering, and gilding, as well as their skill in the use of resplendent gems and semi-precious stones. They also created sacred objects from the bones of revered monks. Meanwhile, Manchu and Han Chinese ingenuity is evident in the adaptation of Tibetan forms and ornamentation to such local media as ceramics, lacquers, and enamels, creating a refined, easy manner with smooth lines, as if made by a brush, another reflection of the pious devotion of the artisans.

Tantric Ritual Objects

Skull cup

The thunderbolt (“dorje” or “vajra”) and bell (“drilbu”) are ritual objects used in Tantric rites that symbolize male and female aspects. The male thunderbolt is a double-headed object held in the right hand. Associated with skill and compassion, it is regarded as indestructible and has the power to cut through ignorance. The bell is held in the left hand. It represents wisdom, emptiness and nirvana. The ritual dagger (“phurbu”) is used in Tantric rituals to “drive the invocation on it way.” Based on a design used by Guru Rinpoche to nail down evil spirits, it has three sides which cut through the core of passion, ignorance and aggression.

The gha a and the vajra are two commonly used ritual implements in Tibetan Buddhism. In Tantric practice, the two are often inseparable, with the right hand (the "method" hand) holding the vajra and the left (the "wisdom" hand) holding the gha a. Together, they represent the union of the forces of compassion and wisdom. The gha a, or bell, is hollow, symbolizing emptiness, while the bell's ringing sound represents the meaning. The vajra has five prongs on both sides, symbolizing the Five Wisdoms (Tathatā-jñāna, Ādarśa-jñāna, Samatā-jñāna, Pratyavek a a-jñāna, and K ty-anu hāna-jñāna). This set of gha a and vajra is housed in a leather box with lacquered decorations, and the description therein indicates that the set, made during Karmapa's time, was worshipped in the Potala Palace in Tibet and was once owned by the second, the third, and the fifth Dalai Lamas.

Prayer Beads

Mala beads (rosaries or prayer beads) are often made of dried seeds. There are usually 108 beads, an auspicious number in Tibetan Buddhism. Praying Buddhists pass their prayer beads through their fingers, keeping careful count of their prayers. A bead is ticked off each time a prayer is recited. A second string is often used to keep track of the higher multiples of prayers.

Tibetan Buddhists also use rosaries made of beads from 108 different skulls. Objects made with human bones are not regarded as gruesome but rather as symbols of the shortness of life and need for religion to facilitate rebirth. Each time the beads are touched, a prayer is said and merit is earned.

Prayer beads, also called counting beads, are used as an aid in Buddhism, Islam, and Catholicism when counting prayers, reciting scriptures, saying incantations, and reading titles. On Bone prayer beads presented by the Panchen Erdeni to the Qing court in 1780, the National Palace Museum, Taipei says: These prayer beads were made from human bones and contain beeswax, coral-made Buddha head beads, lapis lazuli Buddhist pagodas, turquoise, crystals, and gold and silver vajras gadas, exemplifying the solemnness and magnificence of Tibetan prayer beads in the eighteenth century. The bone prayer beads were offered by Lobsang Palden Yeshe (the 6th Panchen Lama) to Emperor Gaozong of Qing in 1780 when the emperor was 70 years of age. [Source: National Palace Museum, Taipei, npm.gov.tw]

Human Thighbone Trumpets and Skull Drums

Skull drum (damaru): Hourglass-shaped drum constructed of two inverted skull caps, symbolic of the joining of the female and male elements of life. Silver band, ornamented with coral and turquoise stones, connects the two halves. Played by rotating, causing the swinging beater to strike each head. Mantras were often written on the interior of drums such as these. Held in the right hand, the "hand of method," the skull drum is an example of the synthesis of tradition that took place between Bön and Buddhist spirituality. [Source: National Music Museum, University of South Dakota usd.edu ^|^]

Tibetans use cups and bowls made of human skulls and flutes carved out of human thigh bones. Some ceremonies at Portala Palace in Lhasa incorporate hourglass-shaped drums fashioned from two skulls, and a container made from a silver-encrusted upside-down skull (the jaw bone serves as the container's lid). Skull drums are usually covered by leather. Sometimes they are covered with human skin. The bones belong to revered lamas and monks.

Rrkang gling (type of thighbone trumpet): Two-section, collapsible horn with stylized sea dragon (makara) bell opening. Constructed entirely of silver, with interwoven foliage design. Very narrow passage at mouthpiece, along with unusual telescoping configuration and attention to detail, suggests that this instrument was a presentation piece for a dignitary or, perhaps, for placement in the hands of a temple deity. ^|^

See Human Thighbone Trumpets and Skull Drums Under MUSIC IN TIBET factsanddetails.com

Buying Some Human-Skull Drums in Kathmandu

Human thighbone flute Isabella Tree wrote in the Sunday Times: “Gingerly, my friend Rosa lifted out the contents of the embroidered case. The object inside was a damaru — a hand drum of the type used in Tibetan Buddhist meditation. When rotated very fast backwards and forwards, tiny pellets suspended on two cords rap the little drums on either side in rhythmic alternation, making a sound to lift the practitioner to a higher awareness. [Source: Isabella Tree, Sunday Times, December 31, 2006]

The hand drum was was made out of human skulls — children's skulls, to be precise. Over the highly polished craniums was stretched a thin membrane of human skin. "One skull is female, the other is male," she explained. "It symbolises the union of wisdom and compassion. It's very powerful. If you get one made out of babies' skulls, that's even better — something to do with the energy flowing through the opening in the fontanelles."

“Rosa is not a Buddhist herself, but she knew enough to be worried about bad karma. "If you don't know where something like this has come from, you have to make sure it has the right energy, that it was made with the right intention. I'm not taking any chances. I'm going to take it to a Rinpoche to get it blessed. Don't want my plane crashing or anything." She was laughing, but I could see she wasn't joking.

The shops around Boudhanath are full of similar objects. In one, I was shown a selection of skull offering bowls; in another, half a dozen trumpets made from women's thigh bones. Dusting one off, the shopkeeper put the hip joint to his lips and blew, making a noise like a hunting horn. This almost jocund familiarity with death is one of the first challenges a westerner faces when encountering Tibetan Buddhism. A tall American I met told me how she'd been in a taxi with a lama when he started measuring her thigh. "What are you doing?" she'd asked him in amazement. "Your thigh bones would make marvellous trumpets," he'd exclaimed. "Would you leave them to our monastery?" Slowly, though, as I became more familiar with them, these ritual implements made of human body parts seemed less macabre. There was something beautiful, even reassuring, in the touch of bone, in the feel of another's — and hence my own — mortality. But to Buddhists, these artefacts are not just reminders of impermanence, of the illusory nature of life; they are power tools, keys to a higher consciousness. There is tantric magic in them.

Later Rosa, received a blessing from a high-ranking lama. “Outside, Rosa was looking distinctly more relaxed. "Rinpoche said the damaru has good karma. I shouldn't be worried. It will bless my flight back. And he said it's right it should be used for its proper purpose." It was incredible to think of the rat-tat-tat of that little skull drum, soon to be conjuring peaks of higher consciousness from a back room in Battersea.

17th Karmapa Lama in White Bone Relics

On white bone relics, the Karmapa Lama wrote: “Relics such as these often come from past Buddhas or Bodhisattvas of the tenth level. “If one has strong faith and devotion, thousands of relics often manifest from just one. It is essential to keep it in a very pure and clean place, cared for very well. Prayers and offerings should be done; otherwise it may not multiply. [Source: Karmapa Lama: His Holiness the 17th Gyalwa Karmapa, Urgyen Trinley Dorje by Ken Holmes, 1995; Ken Holmes' 1995 book, Karmapa =]

“These relic bones are often round, in other dimensions could be considered being a precipitation of bliss arising from the central nervous system of highly realized masters and the activity of the Bodhisattvas. These precious "rinsels" (as they are known in Tibetan) exude a powerful blessing, as they are from the very body of the Buddha and the Karmapa (who is prophesied to be the Sixth Buddha of this aeon). They are often used for the consecration of stupas, temples and shrines. Always treated with the utmost respect, they are kept in special, (preferably high) places and can also be worn for protection and blessings. =

“Usually they are not taken internally. However, they may be taken internally when one is very sick and close to death. When they are used like that, it is said that the essence of the "rinsel" [also ringsel] rests at the crown of one's head. For those with meditative concentration, the "rinsel" will quicken the opening of the crown chakra at the top of the central channel, helping to prevent the possibility of falling into the lower realms upon leaving the body in the moment of death. According to Drupon Dechen Rinpoche of Tsurphu, one who swallows the sacred relic will never go to hell! As previously mentioned, the 20 meter high statue at Tsurphu, the Tsurphu Lhachen, was destroyed during the Cultural Revolution. It contained over two pounds (900 grams) of Buddha Katsyapa's (Buddha Osung — the Third Buddha), sacred bone relics possibly dating back 4,000 years ago! All these precious white bone relics fell to the ground, unnoticed for many years. =

“Another source for these white relics dates back to the late 12th century. Towards the end of the life of the First Karmapa these sacred relics came from this Karmapa's body. A statue of Dusum Khyenpa called "Nga-dra-ma" in Tibetan (literally a statue which "Looks like me" (Karmapa) was built, and these relics — white and generally round as well — were put inside this smaller statue. After the destruction of Tsurphu Monastery remains were found underneath the temple ruins with many white relics around it. =

Prayer wheels

Tibetan Buddhist Prayer Wheels

Prayer wheels are devices inscribed with mani prayers and containing sutra scrolls attached to their axels. Each turn of a prayer wheel represents a recitation of the prayer inside and transports it to heaven. Varying in size from thimbles to oil drums, with some the size of buildings, prayer wheels can be made of wood, copper, bronze, silver or gold. They can be turned by wind or water or rotated by hand and are often stuffed with prayers handwritten in pieces of cloth. Some prayer wheels have handles and look like devices that take up string on a kite. Others are large and hang from temples with thousands of prayers inside that when unraveled are more than a mile long. Pilgrimage paths (“koras”) are often lined with prayer wheel. Pilgrims spin the wheels to earn merit and help them focus on the prayers they are reciting.

A prayer wheel is generally a hollow metal cylinder, often beautifully embossed, mounted on a rod handle and containing a tightly wound scroll printed with a mantra. The external cylinder of a prayer wheel is made out of repoussé metal, usually gilded bronze. The wheel is supported on a handle or axis made of wood or a precious metal. On the outside of the cylinder are inscriptions in Sanskrit (or sometimes Tibetan) script (often Om mani padme hum) and auspicious Buddhist symbols. This outer part is removable to allow for the insertion of the sacred text into the cylinder. The uppermost point of the prayer wheel forms the shape of a lotus bud. The cylinder contains a sacred text written or printed on paper or animal skin. These texts might be sutra or invocations to particular deities (dharani or mantras). The most common text used in prayer wheels is the mantra Om mani padme hum.

Prayer wheels come in many sizes: they may be small and attached to a stick, and spun around by hand; medium-sized and set up at monasteries or temples; or very large and continuously spun by a water mill. But small hand-held wheels are the most common by far. Tibetan people carry them around for hours, and even on long pilgrimages, spinning them any time they have a hand free. Prayer wheels at monasteries and temples are located at the gates of the property, and devotees spin the wheels before passing through the gates. Larger wheels, which may be several yards (meters) high and one or two yards (meters) in diameter, can contain myriad copies of the mantra, and may also contain sacred texts, up to hundreds of volumes. They can be found mounted in rows next to pathways, to be spun by people entering a shrine, or along the route which people use as they walk slowly around and around a sacred site — a form of spiritual practice called circumambulation.

Tibetan Buddhist Prayer Wheel Prayer and Devotion

Prayer wheels are known as Mani wheels in the Tibetan language. According to Tibetan Buddhist belief, spinning a prayer wheel is just as effective as reciting the sacred texts aloud. This belief derives from the Buddhist belief in the power of sound and the formulas to which deities are subject. For many Buddhists, the prayer wheel also represents the Wheel of the Law (or Dharma) set in motion by the Buddha. The prayer wheel is very useful for illiterate members of the lay Buddhist community, since they can "read" the prayers by turning the wheel. [Source: Chloe Xin, Tibetravel.org ]

Prayer wheels often bear the "Om Mani Padme Hum" mantra, seen in Esoteric Buddhism as the root source of all sutras. Practitioners circumambulate, while chanting and contemplating the mantra, as a means of accumulating merit. When merit is satisfactorily accumulated, one becomes a Buddha. Each time Tibetans turn the prayer wheel, they chant the mantra. Buddhist objects for ceremonial use were meant to be dignified and solemn. Written on the column is an Esoteric representation of Buddha, called "Rnam-bcu-dban-ldan," the Tibetan equivalent of the Sanskrit "Kalacakra Dharani," comprised of seven Tibetan letters woven together with three pictographic elements, forming a mandala with Buddha as its focus. [Source: National Palace Museum, Taipei npm.gov.tw ]

Prayer wheels often bear the "Om Mani Padme Hum" mantra, seen in Esoteric Buddhism as the root source of all sutras. Practitioners circumambulate, while chanting and contemplating the mantra, as a means of accumulating merit. When merit is satisfactorily accumulated, one becomes a Buddha. Each time Tibetans turn the prayer wheel, they chant the mantra. Buddhist objects for ceremonial use were meant to be dignified and solemn. Written on the column is an Esoteric representation of Buddha, called "Rnam-bcu-dban-ldan," the Tibetan equivalent of the Sanskrit "Kalacakra Dharani," comprised of seven Tibetan letters woven together with three pictographic elements, forming a mandala with Buddha as its focus. [Source: National Palace Museum, Taipei npm.gov.tw ]

Hand-held prayer wheels are carried by pilgrims and other devotees and turned during devotional activities. Rolls of thin paper, imprinted with many, many copies of the mantra (prayer) “Om Mani Padme Hum,” printed in an ancient Indian script or in Tibetan script, are wound around an axle in a protective container, and spun around and around. Typically, larger decorative versions of the syllables of the mantra are also carved on the outside cover of the wheel. Tibetan Buddhists believe that saying this mantra, out loud or silently to oneself, invokes the powerful benevolent attention and blessings of Chenrezig, the embodiment of compassion.

Theoretically, Buddhist prayer wheels are allowed to slow down but never to stop. They are generally spun very quickly in a clockwise fashion. The merit earned from the written prayer (usually “om mani padme hum” written in Tibetan or Sanskrit) is regarded as weaker than that of a spoken prayer. The more prayers one offers, the more merit he or she earns, which improves his or her chances or receiving a higher reincarnation and eventually achieving nirvana. Yak grease is used on the handle to make them spin more quietly.

Mani Stones in Tibet

Mani stones

Mani stones are flat-surfaced stones carved by Buddhist devotees to earn merit. Most are inscribed with prayer "om mani padme hum" ("Hail to the Jewel in the Lotus"). They are often placed alongside trails near Tibetan-style monasteries and temples. In some places you can find prayer walls, hundreds of meters long composed of mani stones. Travelers should always pass these walls on the left and consequently most prayer walls have trails on both sides.

Mani stones are called Man Zha in Tibetan, meaning “Sanskrit mandala.” In remote areas, far from temples, they serve as prayer halls and shrines for local Tibetans that otherwise have difficulty reaching more conventional places of worship.

Mounds of stones, or cairns, with Mani stones in them can be found almost everywhere, in monasteries, beside villages, crossing, along paths and on mountains. Some of the stones are inscribed with pictures or characters, with prayer flags stuck in the middle usually. Sometimes they are decorated with sheep and yak horns. These are used as places of worship for local Tibetans, especially villagers who have difficulty accessing to temples. There are commonly two kinds of Mani mounds: one is piled by rocks of different sizes and the other is characterized by blocks and pebbles carved with inscriptions and sculptures, which are built in an undulating line.[Sources: Chloe Xin, Tibetravel.org]

Upon encountering a mani stone mound, Tibetan people circumambulate it clockwise as a prayer offering for health, peace, and protection. As a way to earn merit some devout Tibetans pick up a stone and touch it to their forehead, while murmuring mantras and then drop the stone on the mound. This way the mounds get larger and larger. Objects with divine connections such as skulls, horns and the wool of animals and even human hair can be added to the mound. It is believed that requests made to Buddha are answered by circumambulating the mound.

The world's largest Mani stone mound is located in Xinzhai Village of Yushu Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture of Qinghai province. Said to have been started by the first Rinpoche of Jiana after he settled in Gujie Monastery in Xinzhai, the mound became bigger and bigger over the centuries and now reportedly contains 2.5 billion stones. Tens of thousand Mani stones are engraved with words of law, calendar calculation, art theory, sutra texts and Buddha carvings.

Mani stones are regarded as a sacrifice to the Buddha. They can feature different colors and shapes and have different images and texts engraved on them but most are simple ones with the mantra are 'Om Mani Padme Hum'.Mani Stone handicraftsmen are generally peasants or herdsmen in spring, summer and autumn. They only engrave stones in winter. In the old days, Mani stones contained Buddhist texts incantations and mottos accompanied by painted and engraved images to educate illiterate people.

Mani stone walls may be inscribed with characters and pictures produced by an artist. They commonly have the mantra “Om Mani Padme Hum” accompanied by images of deities, monsters, strong animals and other Buddhist-related images. These walls are found near temples and monasteries and can be seen on cliffs faces in Lhasa and Shigatse and other areas. Some regard Mani stones like patron saints that can be stored in a house or taken along when going out.

Butter Sculptures and Tsha Tsha Figurines

Om mani padma hum

Butter sculptures are constructed as offerings. Tibetans make incredibly detailed yak butter sculptures and friezes of flowers, landscapes, trees, temples, human figures animals and god and goddesses. They are made of a mixture yak butter and tsampa (roasted barley) applied on a wooden frame. They are often placed in monasteries at festival time and left there afterwards. One of their purposes is to symbolize the impermanence of all things

Tsha Tshas are small clay figurines unique to Tibet. They can be made with different all materials and can display characteristics associated with different periods and different monasteries. Their small size made them convenient for early Buddhist pilgrims to take. "Tsha-Tsha" are viewed as small stupas or amulets. The Buddhist artwork found on them was introduced from ancient India. There are relief image versions made out from a one-side mold and round stupa versions made with a two-sided mold. [Source: traditions.cultural-china.com, Tibetravel.org]

See Separate Article TIBETAN SCULPTURE factsanddetails.com

Image Sources: Purdue University, Beifan.com, Mongabay.com, Kalachakranet.org, Tibet Government in Exile, Save Tibet

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated September 2022