TIBETAN RELIGION

wrathful Mahakala Tibetans are a very religious and superstitious people. Nearly all Tibetans are Tibetan Buddhists, with the exception of tiny Muslim minority and some who still practice the Bon Religion. But being Tibetan Buddhists doesn't stop Tibetans from being superstitious and practicing folk religions. Many Tibetan villages have a lama (a Tibetan Buddhist priest) and a shaman. Both are called upon to heal the sick, predict the future and read omens for auspicious and inauspicious times.

John Power wrote: Tibetans commonly draw a distinction between three religious traditions: (1) the divine dharma (Iha chos), or Buddhism; (2) Bon dharma (bon chos); and (3) the dharma of human beings (mi chos), or folk religion. The first category includes doctrines and practices that are thought to be distinctively Buddhist. This classification implicitly assumes that the divine dharma is separate and distinct from the other two, although Tibetan Buddhism clearly incorporated elements of both of these traditions. [Source: John Power, “Bon: A Heterodox System”, From Chapter 16 of “Introduction to Tibetan Buddhism”, Snow Lion Publications, 1995. Powers is an American born Professor of Asian Studies and Buddhism who much of his teaching career at the Australian National University in Canberra.]

According to the 2021 Report on International Religious Freedom: China—Tibet: Most ethnic Tibetans practice Tibetan Buddhism, although a sizeable minority practices Bon, a pre-Buddhist indigenous religion. Small minorities practice Islam, Catholicism, or Protestantism. Some scholars estimate there are as many as 400,000 Bon followers across the Tibetan Plateau, most of whom also follow the Dalai Lama and consider themselves to be Tibetan Buddhists. Scholars estimate there are up to 5,000 Tibetan Muslims and 700 Tibetan Catholics in the TAR. Other residents of traditionally Tibetan areas include Han Chinese, many of whom practice Buddhism (including Tibetan Buddhism), Taoism, Confucianism, or traditional folk religions, or profess atheism, as well as Hui Muslims and non-Tibetan Catholics and Protestants.

“Mi chos” (“the dharma of man”) is a folk religion widely practiced in Tibet. Closely linked to Bon and Buddhism, it is concerned primarily with the worship of spirits. Important spirits include “sadak” (lords of the earth, associated with agriculture), “nyen” (which reside in rocks and trees), “tsen” (air spirits that shoot arrows and bring illness and death), “dud” (demons linked to the Buddhist demon Mara), and “lu” or “nagas” (snake-bodied spirits that live at the bottom of lakes, rivers and wells).

Good Websites and Sources: Astrology View on Buddhism viewonbuddhism.org ; Paper on Tibetan Astrology berzinarchives.com ; Bon religion Wikipedia article Wikipedia ; Buddism and Bon in Tibet berzinarchives.com ; Bon Foundation bonfoundation.org

See Separate Articles: RELIGION IN TIBET factsanddetails.com; BON RELIGION factsanddetails.com; TIBETAN BUDDHISM factsanddetails.com; RELIGIOUS REPRESSION IN TIBET factsanddetails.com HISTORY OF articles about TIBETAN BUDDHISM factsanddetails.com 2021 Report on International Religious Freedom: China—Tibet, Office of International Religious Freedom, U.S. Department of State, May 3, 2022 state.gov/reports/2021

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: Religions of Tibet: “The Religions of Tibet” by Giuseppe Tucci and Geoffrey Samuel Amazon.com; “Religions of Tibet in Practice” by Donald S. Lopez Jr. Amazon.com; “Tibet's Sacred Mountain: The Extraordinary Pilgrimage to Mount Kailas” by Russell Johnson and Kerry Moran Amazon.com; “Tantra in Tibet” by Dalai Lama, Tsong-Kha-Pa, et al Amazon.com; “Magic and Mystery in Tibet” by Alexandra David-Neel and A. D'Arsonval Amazon.com; “Mission to Tibet: The Extraordinary Eighteenth-Century Account of Father Ippolito Desideri S. J.” by Fr. Ippolito Desideri S.J., Leonard Zwilling, et al. Amazon.com; Bon: “The Bon Religion of Tibet: The Iconography of a Living Tradition” by Per Kvaerne Amazon.com; “Bon: Tibet's Ancient Religion” by Christoph Baumer Amazon.com; “Flight of the Bön Monks: War, Persecution, and the Salvation of Tibet's Oldest Religion” by Harvey Rice , Jackie Cole , et al. Amazon.com; “Sacred Landscape And Pilgrimage in Tibet: In Search of the Lost Kingdom of Bon” by Gesha Gelek Jinpa, Charles Ramble, et al. Amazon.com; Tibetan Buddhism: “Essential Tibetan Buddhism” by Robert A. F. Thurman Amazon.com; “Initiations and Initiates in Tibet” by Alexandra David-Neel Amazon.com; “The Secret Oral Teachings in Tibetan Buddhist Sects” by Alexandra David-Neel, Lama Yongden Amazon.com; Introduction to Tibetan Buddhism by John Powers Amazon.com; “The World of Tibetan Buddhism: An Overview of Its Philosophy and Practice” by His Holiness the Dalai Lama, Geshe Thupten Jinpa Amazon.com; “The Jewel Tree of Tibet: The Enlightenment of Tibetan Buddhism” by Robert Thurman and Sounds True Amazon.com; “A Concise Introduction to Tibetan Buddhism” by John Powers Amazon.com; “The Preliminary Practices of Tibetan Buddhism” by Geshe Rapten Amazon.com; “Teachings and Practice of Tibetan Tantra” Amazon.com; “Tantra in Practice” by David Gordon White Amazon.com

Tibetan View of Religion

Tibetan Buddhist monks

John Power wrote: The Tibetan language does not even have a term with the same associations as the English word religion. The closest is the word cho (chos), which is a Tibetan translation of the Sanskrit word dharma. This term has a wide range of possible meanings, and no English word comes close to expressing the associations it has for Tibetans. In its most common usage it refers to the teachings of Buddhism, which are thought to express the truth and to outline a path to enlightenment. The path is a multifacteted one, and there are teachings and practices to suit every sort of person. There is no one path that erveryone must follow and no practices that are prescribed for every Buddhist. Rather, the dharma has something for everyone, and anyone can profit from some aspect of the dharma. [Source: John Power, “Bon: A Heterodox System”, From Chapter 16 of “Introduction to Tibetan Buddhism”, Snow Lion Publications, 1995]

Because of its multifaceted nature, however, there is no one "truth" that can be put into words, nor is there one program of training that everyone can or must follow. Tibetan Buddhism recognizes that people have differing capacities, attitudes, and predispositions, and the dharma can and should be adapted to these. Thus, there is no one church in which everyone should worship, no service that everyone might attend, no prayers that everyone must say, no text that everyone should treat as normative, and no one deity that everyone must worship. The dharma is extremely flexible, and if one finds that a particular practice leads to a diminishment of negative emotions, greater peace and happiness, and increased compassion and wisdom, this is dharma. The Dalai Lama even states that one may practice the dharma by following the teachings and practices of non-Buddhist traditions such as Christianity, Islam, Judaism, or Hinduism.2 If one belongs to one of traditions, and if one's religious practice leads to spiritual advancement, the Dalai Lama counsels that one should keep at it, since this is the goal of all religious paths.

In this sentiment he hearkens back to the historical Buddha, Sakyamuni. who was born in the fifth century B.C.E. in present-day Nepal. As he was about to die, the Buddha was questioned by some of his students, who were concerned that after the master's death people might begin propounding doctrines that had not been spoken by the Buddha himself and that these people might tell others that their doctrines were the actual words of the Buddha. In reply, the Buddha told them, "Whatever is well-spoken is the word of the Buddha." In other words, if a particular teaching results in greater peace, compassion, and happiness, and if it leads to a lessening of negative emotions, then it can safely be adopted and practiced as dharma, no matter who originally propounded it.

Tibetan Buddhism

Tibetan Buddhism is a syncretic mix of Mahayana Buddhism, Tantrism and local pantheistic religions, particularly the Bon religion. Its organization, public practices and activities are coordinated mainly by monasteries associated with temples. Religious authority is in the hands of priests called lamas.

Tibetan Buddhism is the main religion of Tibet. It is also practiced by Mongolians and tribal groups such as the Qiang and Yugur in Yunnan, Sichuan, Gansu, Qinghai and other provinces and by Tibetan- and Mongolian-related people in India, Nepal, Bhutan and Russia.

Religion is a daily, if not hourly practice. Tibetans spend much of their time in prayer or doing activities, such as spinning prayer wheels, that earn them merit (Buddhist brownie points that move them closer to nirvana). Like all Buddhists, Tibetans practice nonviolence, do good deeds, present gifts to monks and aspire to have gentle thoughts.

See Separate Article TIBETAN BUDDHISM factsanddetails.com

Tibetan Folk Religion

John Power wrote: The Tibetan folk religion encompasses indigenous beliefs and practices, many of which predate the introduction of Buddhism and which are commonly viewed as being distinct from the mainstream of Buddhist practice. These are primarily concerned with propitiation of the spirits and demons of Tibet, which are believed to inhabit all areas of the country Folk religious practices rely heavily on magic and ritual and are generally intended to bring mundane benefits, such as protection from harm, good crops, healthy livestock, health, wealth, etc. Their importance to ordinary people should not be underestimated, since in the consciousness of most Tibetans the world is full of multitudes of powers and spirits, and the welfare of humans requires that they be propitiated and sometimes subdued. Every part of the natural environment is believed to be alive with various types of sentient forces, who live in mountains, trees, rivers and likes, rocks, fields, the sky, and the earth. Every region has its own native supernatural beings, and people living in these areas are strongly aware of their presence. In order to stay in their good graces, Tibetans give them offerings, perform rituals to propitiate them, and sometimes refrain from going to particular places so as to avoid the more dangerous forces. [Source: John Power, “Bon: A Heterodox System”, From Chapter 16 of “Introduction to Tibetan Buddhism”, Snow Lion Publications, 1995]

In the often harsh environment of Tibet, such practices are believed to give people a measure of control over their unpredictable and sometimes hazardous surroundings. With the almost total triumph of Buddhism in Tibet, the folk religion became infused with Buddhist elements and practices, but it still remains distinct in the minds of the people, mainly because its focus is on pragmatic mundane benefits, and not on final liberation or the benefit of others. By all accounts, Tibetans have always been fascinated by magical and occult practices, and from the earliest times have viewed their country as the abode of countless supernatural forces whose actions have direct bearing on their lives. Since Buddhist teachers tend to focus on supramundane goals, Tibetans naturally seek the services of local shamans, whose function is to make contact with spirits, to predict their influences on people's lives, and to perform rituals that either overcome harmful influences or enlist their help.

When Buddhism entered Tibet, it did not attempt to suppress belief in the indigenous forces. Rather, it incorporated them into its worldview, making them protectors of the dharma who were converted by tantric adepts like Padmasambhava, and who now watch over Buddhism and fight against its enemies. An example is Tangla, a god associated with the Tangla mountains, who was convinced to become a Buddhist by Padmasambhava and now is thought to guard his area against forces inimical to the dharma. The most powerful deities are often considered to be manifestations of buddhas, bodhisattvas, Oikinis, etc., but the mundane forces are thought to be merely worldly powers, who have demonic natures that have been suppressed by Buddhism. Although their conversion has ameliorated the worst of their fierceness, they are still demons who must be kept in check by shamanistic rituals and the efforts of Buddhist adepts. Nor should it be thought that Buddhist practitioners are free from the influences of the folk religion. These beliefs and practices are prevalent in all levels of Tibetan society, and it is common to see learned scholar-lamas, masters of empirically-based dialectics and thoroughly practical in daily affairs, refuse to travel at certain times in order to avoid dangerous spirits or decide their travel schedules after first performingl divination to determine the most auspicious time. Such attitudes may be dismissed as "irrational" by Westerners, but for Tibetans they are entirely pragmatic responses to a world populated by forces that are potentially harmful.

See Separate Article ANIMISM, SHAMANISM AND TRADITIONAL RELIGION factsanddetails.com BON RELIGION factsanddetails.com

Spirits in Tibetan Folk Religion

John Power wrote: According to folk beliefs, the world has three parts: sky and heavens, earth, and the "lower regions." Each of these has its own distinctive spirits, many of which influence the world of humans. The upper gods (steng Iha) live in the atmosphere and sky, the middle tsen (bar btsan) inhabit the earth, and the lower regions are the home of yoklu (g.yog klu), most notably snake-bodied beings called lu (klu naga), which live at the bottoms of lakes, rivers, and wells and are reported to hoard vast stores of treasure. [Source: John Power, “Bon: A Heterodox System”, From Chapter 16 of “Introduction to Tibetan Buddhism”, Snow Lion Publications, 1995]

The spirits that reside in rocks and trees are called nyen (gnyan); they are often malicious, and Tibetans associate them with sickness and death. Lu are believed to bring leprosy, and so it is important to keep them away from human habitations. Sadak (sa bdag, "lords of the earth") are beings that live under the ground and are connected with agriculture. Tsen are spirits that live in the atmosphere, and are believed to shoot arrows at humans who disturb them. These cause illness and death. Tsen appear as demonic figures with red skin, wearing helmets and riding over the mountains in red horses. Du (bdud, mara) were apparently originally atmospheric spirits, but they came to be associated with the Buddhist demons called mara which are led by their king (also named Mara), whose primary goal is to lead sentient beings into ignorance, thus perpetuating the vicious cycle of samsara.

There are many other types of demons and spirits, and a comprehensive listing and discussion of them exceeds the focus of this book. Because of the great interest most Tibetans have in these beings and the widespread belief in the importance of being aware of their powers and remaining in their good graces, the folk religion is a rich and varied system, with a large pantheon, elaborate rituals and ceremonies, local shamans with special powers who can propitiate and exorcise, and divinatory practices that allow humans to predict the influences of the spirit world and take appropriate measures. All of these are now infused with Buddhist influences and ideas, but undoubtedly retain elements of the pre-Buddhist culture.

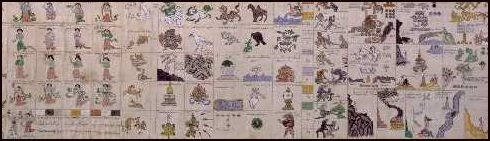

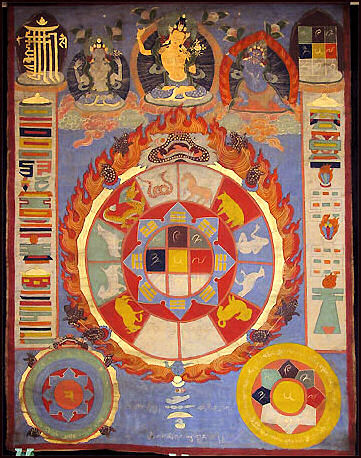

Tibetan astrology symbols

Bon Religion

Before the introduction of Buddhism, animistic worship, generally categorized as Bon , was prevalent in Tibet and the Himalayas. The sun, moon, sky, and other natural elements were worshiped, and doctrine was transmitted orally from generation to generation. Bon, from a Tibetan word meaning invocation or recitation, has priests — bonpo — who perform exorcisms, burial rites, and divinations to tame threatening demons and to understand the wishes of the gods. [Source: Andrea Matles Savada, Library of Congress, 1991]

Bon religion is an ancient shamanist religion with esoteric rituals, exorcisms, talismans, spells, incantations, drumming, sacrifices, a pantheon gods and evil spirits, and a cult of the dead. Originating in Tibet, it predates Buddhism there, has greatly influenced Tibetan Buddhism and is still practiced by the Bonpo people. Prayer flags, prayers wheels, sky burials, festival devil dances, spirit traps, rubbing holy stones — things that are associated with Tibetan religion and Tibetan Buddhism — all evolved from the Bon religion. The Tibet scholar David Snellgrove once said “Every Tibetan is a bonpo at heart.”

In 2019, scholars estimated that there were 400,000 Bon followers in the Tibetan plateau. When Tibet was invaded by Communist China in the 1950s, there were approximately 300 Bon monasteries in Tibet and more in western China. Bon suffered the same fate as Tibetan Buddhism did during the Chinese Cultural revolution, and many many monasteries were. Some were rebuilt after 1980. Bonpo is strongest in small hamlets in isolated valleys in eastern Tibet, parts of the Chhnagtang in northern Tibet and the Aba region of northern Sichuan. [Source: Wikipedia]

See Separate BON RELIGION factsanddetails.com

Tibetan Superstition and Astrology

Tibetans can be very superstitious and superstition, religion, culture and science are often intertwined. A lot of importance is placed on the date and time a person is born in astrological terms. Decisions are often made depending on one’s astrological sign. Tibetan year astrological signs are more or less the same as Chinese ones.

Monks serve as oracles, mediums and exorcists. Astrologers are consulted before for all kinds of occasions and events: marriages, funerals, births, journeys, archery contests. Beliefs in magic go all the way to the top: The Dalai Lama still consults the official state oracle, a monk who divines the future from a temple complex. Students at the Astrological Institute in Changkha take a five years course that includes courses in philosophy, literature and mathematics.

Confidence in the supernatural is common among Tibetans, though not universally celebrated. Jamyang Norbu, a prominent writer and critic of the Dalai Lama, told The New Yorker he bemoans the practice of "burying our collective head in the sands of superstition and inertia." [Source: Evan Osnos, The New Yorker, October 4, 2010]

Kao Tein-en, a Chinese expert on Tibetan Buddhism, told AFP: “Astrology and fortune telling are part of Tibetan culture, and the masters capable of doing these things are in a different spiritual dimension from the rest of us...The masters have their special ways to communicate with nature and applying that unique knowledge to the daily lives of common people...which can be explained by modern science.”

The people in some parts of Tibet believe that the world is flat and shaped like half moon; that the sun looks bigger in distant lands; and that Russians have horns and tails.Tibetans have traditionally believed that their race descended from an ugly, sex-starved witch who had sex with a monkey and bore six children. They believe that Mt. Kailas is the center of the universe and that the god Mahaba (represented by the constellation Orion) races across the sky in pursuit of the abductors of his wife (represented by the Pliades).

Taboos and Superstitions in Tibet

1) Don't touch the head or shoulders of a Tibetan. 2) Don't step across or tread on others’ clothes. 3) Never step across from one's body. 4) Don't step across or tread on the tableware. 5) Don't spit or clap your palms behind the Tibetans. 6) Don't kill any animals or insects in monasteries. 7) Don't drive away or hurt vultures or eagles, for they are holy birds for Tibetans. [Source: Chloe Xin, Tibetravel.org tibettravel.org]

8) Women clothes, especially, women pants and underpants are not supposed to be aired to dry in a place where people pass. 9) Don't whistle or shout or cry inside a house. 10) One is not supposed to sweep the floor or throw out the trash after some family member goes away from home, or guests have just left, or at noon or after the sunset, or on the first day of Tibetan New Year. 11) Non-relatives can not mention the name of the dead face to face with the relatives of the dead. 12) Tasks, such as knitting a sweater or making a carpet, should be finished before the end of the year.

13) One should not go to the house of others at twilight, especially when there are women who's going to give birth to a baby or have just given birth to a baby, or heavily ill people in that house. This especially applies to strangers. 14) Objects are not allowed to be taken outside a home after noon. 15) Two family members are not supposed to go out at the same time if they are headin opposite directions. They should go outside at different times. 16) Tibetan women can not comb or wash their hair in the evening, neither can they go outside with their hair not being tied up.

17) Don’t walk over an appliance, utensil or bowl that is used for eating. 18) When you are using a broom and dustpan, you can transfer them from one hand to another. But you must put them on the ground at first, and someone will pick them up from the ground and hand them to you. [Source: Chloe Xin, Tibetravel.org tibettravel.org ]

Lucky and Unlucky Numbers in Tibet

In Tibetan culture, the odd numbers are always regarded as auspicious number by local Tibetans. “13" is a lucky and holy number for Tibetan people. "6" is also considered as a lucky number for it is the multiple of "3". Tibetans always deal with some important matters or travel to some place far from home on odd days. [Source: Chloe Xin, Tibetravel.org tibettravel.org, June 3, 2014]

We can also find out about lucky numbers in Tibet from Tibetan drinking customs. Tibetan people always clink their glasses three times, and drink three glasses of after each clinking. Hence, they would always drink nine glasses of chang or whatwver once a clinking is proposed and nine glasses is regarded as a sign of basic respect between friends. Gifts given to Tibetan people should be odd numbers and never be even numbers. During the celebration of Tibetan New Year, the lamas in the monasteries are given gift bags (filled with various dried fruits). The number of the gift bags should always be odd numbers and never be even numbers.

Tibetans connect nice things with "3", such as the three Buddhas, three monasteries, three tribes and three sages. They also use "3" to express something auspicious or some other lucky symbols. In Tibetan Buddhism culture, a lot of nouns use "3"as their affix. For example, "3" was used to symbolize the sun, moon and star. In Tibetan Buddhism, the universe is divided into three parts, the sky, ground and underground. The three Buddhas of Longevity refers to Amitayus Buddha, Ushnisha Vijaya and White Tara.

The odd number "9" means everything to Tibetans. The "9 rivers" means the place where all the rivers join together. "9 people" means all living creatures. "9 needs" means all the needs and "9 wishes" means all the wishes. In a word, "9" is always used to express "much" in Tibetan. The number "9" is also regarded as lucky among the ancient Han people and modern Chinese. In ancient times, Han people use "9" to express uncertainty, much and endless.

In the West, the number 13 is regarded as an unlucky number, but in Tibetan culture 13 is an auspicious number, a holy number. In the ancient Tibetan fairy tales, the heaven is composed of 13 layers. The 13th layer of the heaven is said to be the desireless pure land described by Master Tsongkhapa. Devout pilgrims always do 13 koras (circumambulations) around Mt. Kailash to pray for happiness and cleanse ones’ self of guilty.

According to King Gesar, a Tibetan story regarded as the world's longest epic, when Gesar was born he held 13 flowers in his hands, walked 13 steps and vowed to become a Buddha at 13. Indeed, when he was 13, he was victorious in a horse race, married and became king of the state of Ling. Also according to King Gesar, Gesar had 13 concubines and 13 Buddhist guardians, and in the state of Ling under his rule there were 13 snowy mountains, 13 mountain ridges, and 13 lakes. [Source: “The Mystery of Numbers” by Annemarie Schimmel, 1996]

Tibetan astrology thangka

Tibetan Folk Customs

Many Himalayan people protect their homes from evil spirits by smearing a layer of cow dung on the floor and making balls with sacred rice and cow dung and placing them on top of the doorway. The Mustangese set up demon traps and bury horse skulls under every house to keep demons out. If an abnormally high number of hardships occur at one house a lama may be called in to exorcize demons. Sometimes he does this by luring the demons into a dish, praying, and then tossing the dish into a fire.

Instead of saying grace before a meal Tibetans often dip their forth finger into their tea and flick the droplets in the four directions. To forecast, the weather salt is thrown into the air and then tossed onto a fire. If it crackles it means a storm is far away if it stays silent it means a storm in near.

Before a caravan begins, a consultation with the gods using a lama or shaman as an intermediary takes place and yak butter is placed on the brow and horn tips of each yak with the understanding that gods like butter and will protect the animals to show their gratitude. These rituals are believed to offer protection from rock slides, blizzards, falls from cliffs and dangerously cold and wet weather.

Before a caravan sets off shaman make sacred balls of rice and cow dung and spread them on yaks, goats, sheep and other animals in the caravan. The caravan leader sacrifices a lamb to the god of the forest and brings the shaman back a temple bell from Tibet. Wives dab yak butter on the heads of their husbands before a journey for protection from evil spirits.

In some villages, lamas have decreed that families can not leave their houses on certain days. Explaining why the start of a caravan was delayed, one caravan leader explained, "I must not leave my house on Tuesday because it is an evil day, and will be bringing bad luck upon my house. We will have until Wednesday." The edict can be circumvented by sleeping in someone else's house before the inauspicious day approaches.

When a caravan is ready to embark on a journey to the lowlands, the event is heralded with handfuls of barley thrown into the air and chants from lamas and honks from conch shell horns. The leader of the caravan thrusts his arm into the chest of a slaughtered sheep and draws out a cup of blood, which he drinks slowly. This is done to protect him from malaria and dysentery. [Source: Eric Valli and Diane Summers, National Geographic, December 1993]

Catholics in Tibetan Areas

Catholicism penetrated into some remote Tibetan-occupied places. Cizhong, a village in Yunnan near the Tibetan border, three hours on a bad road from the nearest town, is the home of a European-style Catholic church built more than a century ago by Catholic missionaries. Around 600 of the village’s 1,000 residents are Catholics. They go to church every Sunday, sing chants from a hymnal called "Chants in Religeux Thibetan."

French priests brought their religion to Yunnan in the 1860s and the community endured through the Mao era and the Cultural Revolution. Most of the members are Tibetans. Many arrive at church on Sunday after walking for more than an hour from their mountain homes.

The Cizhong Catholic community has no permanent priest. Their church is decorated with lotus flowers and yin and yang symbols. Christian hymns are sung to Tibetan highland melodies. Communion is performed with wine made from locally grown grapes. Mass features a dance around a bonfire, presided over by a priest that comes to the village only two or three times annually. Christmas is also celebrated with dancing around a bonfire.

Taiwan, Tibetan Buddhism and Superstition

In Taiwan, Tibetan Buddhism is known as the Secret Sect. Lamas are believed to have the ability to see into the future and have the power to change a person destiny using items such as crystal balls, mirrors, flutes, wind chimes, swords and colored threads. Monks perform feng shui — the auspicious positioning of structures and furniture — on homes and offices.

Taiwanese purchase items touched by monks for good luck. Businesses consult Tibetan monks on ways to make more money and politicians seek their advise in winning elections. Some Taiwanese believe that Dalai Lama has magical powers and have offered to pay tens of thousands of dollars for him perform initiation rituals on them.

Image Sources: Antique Tibet, Purdue University, Kalachakranet.org, Tibetan art.

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated September 2022