OROQEN LIFE

Traditionally the Oroqen lived in teepee-like tents, known as “xianrenzhu”, or “sierranju”, which were supported by thirty long poles and covered with birch bark in the summer and deerskin in the winter. The dwellings were usually about six meters in diameter and five meters in height. At the center was a fireplace used for cooking, warmth and lighting. Xianrenzhu were usually set up by a river in a single line or an arch by a mountain slope. By the 1950s, most Oroqen had moved to brick and tile houses provided by the Chinese government. They still erect xianrenzhu, sometimes outside their homes or in the forest to use for recreational purposes the same way Mongols do with gers (yurts).

Birch bark is also used to make baskets, tools, utensils and canoes, and deerskins is used to make boots, clothes and sleeping bags. Oroqen women made beautiful boxes, bowls and basins from birch bark and were known for their skilled needlework. Girls are taught by their mothers when they are still very young to rub fur, dry meat and gather fruit in the forest. Oroqen girls start to do household work at 13 or 14.

The Oroqens are an honest and friendly people who always treat their guests well. People who lodge in an Oroqen home would often hear the housewife say to the husband early in the morning: "I'm going to hunt some breakfast for our guests and you go to fetch water." When the guests have washed, the woman with gun slung over her shoulders would return with a roe back. Some of them still preserve the pillar to the immortals near their house. [Source: China.org]

In the old days life was hard. Shortages of food were a concern. Many Oroqen made their living by hunting, raising and herding reindeer, whose embryos, penises, tails and antlers are used in Chinese medicine. Many Oroqen still subsist off of fish, reindeer meat and wild plants. Meat is often preserved by smoking or drying. Raw reindeer liver is considered a delicacy. Fermented mare's milk is a popular alcoholic drink. It is not clear how much the Oroqen have been affected by modern life and many of the their old traditions remain.

Oroqen hunting traditions are dying. Many of those who even remember them are very old. An Oroqen named Bai Ying, who has workers a cultural researcher in Beijing told Time, “They can’t adjust to the rhythm of modern life. They can’t farm, so they drink every day.” There days many Oroqen children speak only Mandarin and the Oroqen are a minority in their own banner. Of the 300,000 people that live their 90 percent are Han Chinese. Many others are Mongolians. On assimilation, Hing Chao, chairman of the Hong Kong-based Orochen Foundation, told Time. “They are assimilated, yes, but they are not integrated into the mainstream of society.”

See Separate Article OROQEN factsanddetails.com ; REINDEER factsanddetails.com REINDEER AND PEOPLE factsanddetails.com; ETHNIC GROUPS IN NORTHERN CHINA factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: “The Oroqens: China's Nomadic Hunters” by Pu Qiu (1983) Amazon.com; “Ethnic Chrysalis: China’s Orochen People and the Legacy of Qing Borderland Administration (Harvard-Yenching Institute Monograph Series) by Loretta E. Kim Amazon.com; “Leaving Footprints in the Taiga: Luck, Spirits and Ambivalence among the Siberian Orochen Reindeer Herders and Hunters” by Donatas Brandišauskas Amazon.com; “Reindeer Herders in My Heart: Stories of Healing Journeys in Mongolia” by Sas Carey (Author) Amazon.com; “The Minorities of Northern China: A Survey” by Henry G. Schwarz (1984) Amazon.com; “On the Edge: Life along the Russia-China Border” by Franck Billé and Caroline Humphrey Amazon.com

Old Oroqen Way of Life

In the past most of the Oroqen lived off hunting, gathering and fishing. They went on hunting expeditions in groups, and the game bagged was distributed equally not only to those taking part in the hunt, but also to the aged and infirm. The heads, entrails and bones of the animals killed were not distributed but were cooked and eaten by all. Later, deer antlers, which fetched a good price, were not distributed but went to the hunters who killed the animals. [Source: China.org ]

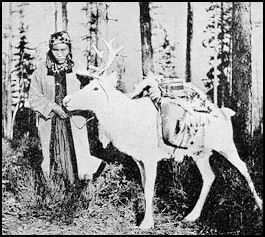

woman and reindeer Oroqen used to live in teepee-like tents—the immortals pillar— supported by a center pole. Around the pole there were frames of branches, which supported a wall made of bark or animal pelts. There was no floor. Horses, guns and hunting dogs were their most valued possessions." Their short but strong horses were well suited for hunting in the forests. For hunting they used whistles to attract game and guns to kill it. What they killed was often smoked for preservation so it oculd be eaten anytime. They also fished from boats made with birch bark. Women and children gathered wild herbs and vegetables. [Source: Ethnic China *\

The Oroqen were nomads to some degree that traveled according to the season and the habits of the game the pursued. They moved their tents in small carts pulled by their horses. Starting fires was difficult so they carried burning embers with them. In the past, the Oroqen used the skins of roe deer to make their clothes. From the hats on their heads to their trousers and boots, everything they wore was made of the same material—roe skin, sometimes embroidered with simple patterns. They made quilts with the skin of roe and other animals. On festive days, Oroqen women wore decorated headwear. Most of their daily-used utensils were made of animal pelts or birch bark. *\

Reindeer in China

Reindeer are commonly called the “nondescript animal” in China because they have horse-like head, deer-like antler, donkey-like body and cattle-like hoofs, but they are different from each of these four animals. Reindeer are well adapted for cold weather. They are fond of eating moss, and manage well in remote mountainous forests, swamps, or deep snow. [Source: Liu Jun, Museum of Nationalities, Central University for Nationalities, Science of China ~]

The reindeer in northern China are believed to have originated from wild animals in northern Russia. They were caught and domesticated by hunting groups in China and Russia such as the Ewenki and Oroqen and used in a number of ways in daily life. The Ewenki became the last ethnic group in China to breed and use reindeer after the Oroqen gave up the reindeer in favor of the horse.

Reindeer generally measure around two meters in length and one meter in height, and weigh from 100 kilograms to 150 kilograms. The colors of their hair includes a dust-color, white, black and gray. Their tails are usually short. There is a long tuft of hair under the neck. Males are larger and taller than females. Their life-span is generally 15 years to 20 years. Most of the females in deer family have no antlers, but among reindeer both sexes grow a pair of branched antlers. The size of the antlers and amount of the branches vary according to age. The antlers fall off in the autumn and grow again in March or April the next year.

Reindeer are meek by nature. They never kick or bite people and are relatively easy to raise. They are usually raised by women. It is not necessary to enclose them with a fence, or feed them. You can just put them out to graze. They leave the campsites when night comes, gathering in herds and grazing in the forests, and come back at dawn. They don't leave in the daytime. The reindeer are good at finding food. Even in the winter, when the mountain paths are sealed by snow, they can also use the broad forepaws to dig up into the snow, as deep as one meter, to look for mosses to eat. Reindeer like salt. Their masters can knock on the salt box if they want to use the reindeer. They will follow the sound and come.

Reindeer are very strong. They can bear a burden of more than 40 kilograms and cover more than 32 kilometers per day. They are indispensable in the productive and daily life of hunters, because their relatively light weight and broad hoofs allow them to walk for a long time in deep snow, swamp or dense forest. People use the reindeer to transport hunted animals and articles for daily use, such as cookers, foodstuff, clothes, and fabric and birch bark that can be used to make tents.

Oroqen Families, Clans and Marriage

In the old days, generally, a single Oroqen family occupied an immortal pillar (tent). Often several families with blood ties lived and traveled together in groups called wulileng. Wulileng were the basic unit of Oroqen. Members of a wulileng worked together and shared the products of their work. Men were usually were hunters. Every wulileng had its own hunting fields, usually with a river flowing through it . [Source: Ethnic China *]

Nomadic Oroqen carried their babies inside a cradle when on the move and hung the cradles inside the tent when they camped. The cradle was decorated with hanging cloth figurines— images of the gods—that were supposed to protect the children by scaring off evil spirits and ghosts. When somebody died, the corpse was hanged from the branches of a tree until it rotted, and then it was brought down and covered by stones. *\

Monogamy is practiced by the Oroqens who are only permitted to marry with people outside their own clans. Marriages have traditionally been arranged.Proposals for marriage as a rule are made by go-betweens, sent to girls' families by boys' families. Before the wedding officially took place the couple slept together in the house of the bride’s parents to mark the sanctifying of the marriage contract and gift-giving ceremonies. After the wedding the couple went to live with the groom’s clan. Divorce was uncommon. Widows were required to wait three years until they remarried. If a son had been born, she was required to remain a widow all her life. Property was passed down through the male line; a divorced woman was not allowed to take even the dowry she brought from her own parents. [Source: Liu Xingwu, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 6: Russia-Eurasia/China” edited by Paul Friedrich and Norma Diamond, 1994 |~|]

Liu Xingwu wrote in the “Encyclopedia of World Cultures”:“Until the middle of the seventeenth century the Oroqen were organized into seven exogamous clans, called mokuns, with marriages taking place outside clan . A mokunda, the head of a clan, enjoyed high respect and authority. Decisions were made by consensus. Later, to provide marriage partners, new clans evidently split off following solemn religious ceremonies. These clans developed into wulilengs, meaning “offsprings," comprised of patrilineal families. Wulilengs were basic economic units, each managed by a democratically elected tatanda. Use of iron implements, horses, and shotguns soon changed Oroqen social Organization, with nuclear families replacing wulilengs as the basic economic unit. Each family was free to join or leave a wulileng, and the title of tatanda was only used for hunting leaders. |~|

Oroqen Customs and Taboos

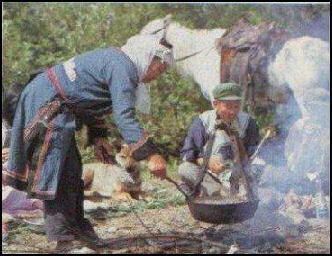

Hunter's camp The Oroqen have traditionally had many taboos. It was considered a taboo to kill bears for example. Some important ceremonies revolved around placating disturbed bear spirits. If a bear is killed in self defense its bones had to be spread on a structure made willow branches to ask for forgiveness. There were also taboos regarding women and hunting. Special boxes associated with hunting gods were not to be touched by women. Women were not supposed to walk behind tents and had to give birth in a special tent or hut. Specific plans were never made for a hunt because it was widely believe they prey were able to sense such plans.

One taboo prohibited a woman from giving birth in the home. She had to do that in a little hut built outside the house in which she would be confined for a month before she could return home with her newborn. [Source: China.org ]

The Oroqens have a long list of don'ts rooting in their hunting traditions and way of life in the forests. For instance, they never call the tiger by its actual name but just "long tail," and the bear "granddad." Bears killed are generally honored with a series of ceremonies; their bones are wrapped in straw placed high on trees and offerings are made for the souls of dead bears. Oroqens do not work out their hunting plans in advance, because they believe that the shoulder blades of wild beasts have the power to see through a plan when one is made.

Oroqen Teepee: the Immortal Pillar

"The immortal pillar" (also called a slashing pillar and known in Oroqen language as a "wooden pole horse") is the name of the traditional Oroqen dwelling—a teepee-like tent built by using twenty or thirty five-to-six meter-long wooden poles, animal skins and birch bark. Constructing an immortal pillar is very simple: 1) use several wooden poles—which have branches on top that help to hold the other poles up—to prop up a conical framework of poles with a slope of 60 degree. 2) Add other wooden poles to the framework with the proportional spacing similar to that of an umbrella. 3) Cover frame with deer skins and birch bark.[Source: Liu Jun, Museum of Nationalities, Central University for Nationalities ~]

The "immortal pillar" is built to keep out rain in summer and cold and snow in the winter—and it can be bitterly cold, as cold as Siberia, where the Oroqen live. Like a teepee there, there is a hole at the top, where the branches come together, to let in the light and let out smoke when a fire is going. The door is located in the south or southeast part of the house. The cover of the immortal pillar is changed with the seasons. In winter, it is mostly covered in deer skin.

About 50 or 60 deer skins are needed. In spring, birch bark is the preferred material. To prepare the birch bark, the hard external layer is removed and the internal soft layer is heated to make it softer and tougher. Threads made from horsetails or deer and elk tendons are used to sew together the small pieces of bark together to form several large pieces. The coverings are placed over the frame from bottom to top, one layer over another, fixed on the wooden poles with pitons and straps in the corners. In winter, the immortal pillar is built on the leeward of hills with a sunny exposure while in summer, it is mostly built in on the place with a good breeze. ~

Orochen tents (Orochen are similar to the Oroqen)

The inner furnishings of the immortal pillar are very simple and consist mainly of beds for sleeping. There are two kinds of beds: one is the shakedown which is made by directly laying wood, hay, birch bark and deerskins on the ground. The other is the doss which is made by erecting wooden stakes to set up a bed. In a immortal pillar, people can sleep on the three sides, with the other side left for door. In the middle of the dwelling is a fire for warm and an iron boiler on the fire, which can be used to prepare a meal or hot drink. ~

The framework of the immortal pillar is very simple and is easy to put together and take apart. The materials are very easy to gather from the forest—a product of the Oroqen's hunting life. Even when they were nomads, the Oroqen sometimes settled temporarily in "Mukeleng" houses built with logs. After they were settled, the Oroqen began to live in tile or concrete structures with normal roofs and windows. Some Oroqen families still raise immortal pillars outside their modern homes or build them temporarily in winter for shelter from cold or when they go out hunting. ~

Oroqen Food: Roe Meat and Wormwood Buds

The traditional food of Oroqen is mainly the game meat and fish, in which the meat of the roe deer was favored followed by the meat of deer, elk, bear and boar. Roe meat tastes fresh and tender, the Oroqen say, and is rich in nutrition. In the past, there were many roes in the forests of the Great and Small Xingan Mountains, so roes were the primary target of hunting and the source of clothes for Oroqen people. [Source: Liu Jun, Museum of Nationalities, Central University for Nationalities ~]

The Oroqen cook roe meat many ways: bake it, steam it, braise it, but stewing it to be eaten with the hands is the most common way. Half-cooked, even with some blood, is regarded as the best. Hunters have traditionally liked eating the kidney and liver of roes. Every time they kill a roe, they take out the kidney and liver on the spot and share it and eat it. They believe that eating the raw kidney and liver is good for their eyes and health. ~

At weddings, festivals and feasts, the Oroqen prepare a rich feast of roe meat, with a variety of roe meat dishes. According to tradition, at an Oroqen wedding, both the bridegroom's family and the bride's family prepare a roe meat feast. A respected elder is put in charge of this roe meat wedding feast. The roe deer are supposed to be captured alive and slaughtered and prepared at the wedding feat. The deer skin is supposed to be singed on fire so the smoke spreads everywhere, letting everyone share the happiness and joy of the wedding. ~

In the past, the Oroqen people didn't grow vegetables and the wild wormwood bud was their favorite and most important plant dish. Even now, when Oroqen have access to a wide variety of vegetables and their diet has changed a lot, their passion for wormwood bud is undiminished. The wormwood bud grows wild along river sides. Oroqen describe the taste as fresh and fragrant. The wormwood is also considered a highly-prized medicine plant useful in treating colds, fevers, stomachaches, hypertension and diabetes. Every spring and summer, the Oroqen women go out with baskets and collect wormwood buds. They can be braised with meat or fish or fried and slathered in sauce. Sometimes they are pickled and preserved to be eaten later.

Oroqen settlement in the 1950s

Oroqen Roe Deerskin Clothes

Oroqen have traditionally worn clothes made from skins of animals they hunted. They wear leather clothes in winter, spring and autumn, and even in summer, especially when they go hunting in the mountain because the leather clothes can keep out cold and are waterproof and wearable. Oroqen women like to wear roe skin gloves with all kinds of patterns of birds or animals sewed on them. [Source: Chinatravel.com \=/]

An Oroqen “Girl’s Robe with Banded Hem and Patched Motif” is on display at the Shanghai Museum. According to the museum: Roe deer hide of different seasons can be made into different clothes for men and women of all ages. Roe deer skin is also made into quilts, cushions, even small tents to shelter from the wind and rain. The robe is the main style of Oroqen clothing, with fur coat and leather pants inside and fur lined robe and leather chaps as outer wear, with accessories including leather socks, hats and boots. The roe deer fur hat is made from a complete scalp of a roe deer, which is very deceptive. To prevent friendly fire during hunting, they will patch a piece of black leather on the eye socket, and change the two ears to false ones. The roe deer leather clothing and supplies are both long wearing and proof against the cold. [Source: Shanghai Museum]

The Oroqen's traditional way of living is "eating meat and sleeping on the fell", with “fell” meaning a roe deer skin and fur. During the long life of hunting, the Oroqen displayed their originality and resourcefulness by putting roe deer skin to numerous uses and developing a whole culture around it. Their clothes—from hat to shoes—their bedclothes and tent covers and household goods were mainly made of roe fell. Roe fell is not only durable it is also waterproof and good at keeping out cold. Roe fell of different seasons can be used to make different kinds of clothes. The roe head winter hat, for example, is made of autumn and winter roe fell, which is very thick and tough and has long and dense hair. The roe fell of summer has short and sparse hair, abd is suitable for spring and summer dress. [Source: Liu Jun, Museum of Nationalities, Central University for Nationalities ~]

Oroqen clothes consist mainly of robes and gowns and includes fur robes, fur jackets, fur trousers, chaps, fur shoes, fur socks, fur gloves, fur waistcoats, and roe head hats. The roe head hat is the most unique and distinctive. It is made completely from the fur of a roe deer head and looks like a deer head. To make one: 1) take off the skin and fur from the roe head and steam it. 2) Place two pieces of black fur on the two holes of eyes. 3) Cut off the two ears and sew up two artificial ears made of roe fell. Retain the roe horns. This kind of hat not only keeps one warm, it also is the perfect disguise for of hunting. The artificial ears are added in part so hunters can tell the difference between a roe head hat and a real roe deer and not take a shot at the hat and its wearer.

modern Oroqen settlement

Oroqen Culture

Oroqens enjoy dancing and singing. Men, women and children often gather to sing and dance when the hunters return with their game or at festival times. The Oroqens have many tales, fables, legends, proverbs and riddles that have been handed down from generation to generation.

The Oroqen have a rich and varied repertory of folk songs. They sing praises of nature and love, hunting and struggles in life in a lively rhythm. Among the most popular Oroqen dances are the "Black Bears Fight" and "Wood Cock Dance," at which the dancers execute movements like those of animals and birds. Also popular is a ritual in which members of a clan gather to perform dances depicting events in clan history. [Source: China.org |]

"Pengnuhua" (a kind of harmonica) and "Wentuwen" (hand drum) are among the traditional instruments used. Played by Oroqen musicians, these instruments produce tunes that sound like the twittering of birds or the braying of deer. These instruments are sometimes used to lure wild beasts to within shooting range. Pelts prepared by Oroqen women are soft, fluffy and light, and they are used in making garments, hats, gloves, socks and blankets as well as tents. |

Both men and women hunt and fish, though normally these activities were pursued by men. Young women were trained in tanning, drying meat, collecting, and needlework. The Oroqen are excellent tanners and make handsome leather works. Their embroidery is known for its delicate and exquisite designs. They also make beautiful basins, bowls, boxes, and other containers out of birch bark, with bird, animal, and flower designs. Oroqen women cshow extraordinary skill in embroidering patterns of deer, bears and horses on pelts and cloth that go into the making of head gears, gloves, boots and garments. Oroqen women also make basins, bowls, boxes and other objects from birch barks. Engraved with various designs and dyed in color, these objects are artistic works that convey the idea of simplicity and beauty.

Oroqen Birch Bark Products and Crafts

The Oroqens have preserved the birch bark culture in northern China. Most of their daily utensils are made of birch barks, such as bowl (A Shen in the local language), basin (A Han), wooden cask (Mulin Kaiyi), basket (Kunji), sewing box (Ao Sha), box (Ada Mala) and the curtain put around the poles of their houses (Tiekesha). All of these tools have colored patterns on them and are very beautiful. [Source: Chinatravel.com]

Oroqen cradle

There are many birch trees in the Great and Small Xingan Mountains where the Oroqen people live. The diligent Oroqen are as resourceful and creative with the things they make from birch bark as they are with roe fell. They make birches and barks into various household appliances and crafts, including birch bark vessels and birch bark boats. [Source: Liu Jun, Museum of Nationalities, Central University for Nationalities]

In the early summer, birches are rich in sap and moisture and this is regarded as the best time to harvest birch bark. The Oroqen select sturdy, straight and smooth birches. They use a knife to make gashes around the trunk on the top and bottom and then make a gash between the top gash and the bottom gash. They use hands to peal off the bark, and try to get as large of piece as possible. New bark grows where the bark was peeled off.

Oroqen have traditionally been skilled as craftsmen of making products using birch bark and threads made from twisted horsetail hair or roe, deer or elk tendons. They sometimes carve various patterns on the products. Large-sized articles include suitcases, water pot and baskets. Among the mid-sized ones are basins, hatboxes, needle and thread boxes and the little barrels used for collecting and storing wild fruits. Small articles include bowls, cigarette cases and medicine boxes. Birch products are easy to make, solid and endurable. They are relatively waterproof and portable.

The Oroqen also have traditionally used birch bark to build boats. These boats are long and narrow and somewhat like a canoe. Generally, the width is less than 1 meter and the length is about 5 meters. The boat's framework is made up of two logs (or long pieces of wood) covered by a large piece of birch bark without holes. There are no metal nails in the boat. Every part of the boat is fixed with nails made of wood. Two or three persons can fit into this kind of boat. People can row the boat with a single oar. The rowing produces little sound, which is helpful when hunting, making it is easy to get close to game. One person can cross the river by using this boat and bind the boat to his body and carry it.

Oroqen Sleighs and Skis

In the homeland of the Oroqen, there are many mountains, trees and creeks, making transportation difficult. Snow and ice can last six or seven months. In the old days, Oroqen used reindeer, horses, sleighs, skis and birch bark boat to travel through the woods and across the snow. Reindeer were once the important means of transport for the Oroqen people but because reindeer are relatively slow and have relatively small carrying capacities, they were gradually replaced by horses that are faster and have a larger carrying capacity. Even now horses continue to be widely used by the Oroqen. [Source: Liu Jun, Museum of Nationalities, Central University for Nationalities ~]

shaman jacket made with cowrie shells

Sleighs and skis have also played important roles in Oroqen's life. To make a traditional Oroqen sleigh is simple: use two curved wooden poles as the bottom for runners and install four wooden stakes and a beam on it for the carriage. This kind of sleigh was very basic but it was convenient for carrying loads through the winter forest. The Oroqen used to carry the necessary household articles on this kind of sleigh to their hunting grounds. ~

Primitive skis have been used for a long time in Oroqen areas. In the old days, the Orqen liked to hunt in the winter because it was easy to track animals in the snow. Every year, when the mountains became sealed by heavy snow, hunters donned skis to search for animals and ordianry oroqen wore them to make visits and pass message. The skis were generally made of the solid and whippy wooden planks of birch or larch. The front of the ski was curved upwards. There was a fur sheath for the foot in the middle of the ski. Oroqen used two kinds of skis: short ones and long ones. The long skis were about two meters long and the short ones were about one long. The longer skis were stiffer and faster and suitable for travel on flat areas in snow that wasn’t too hard. The shorter skis were lighter and more flexible and more suitable for travel through woods, on slopes and on harder snow. Skis fixed with boar skin at the bottom slid better on flat and downhill surfaces and gripped better going uphill. ~

Oroqen Hunting

The Oroqen have traditionally been expert hunters. Both the males and females were sharp shooters on horseback. Boys usually started to go out on hunting trips with their parents or brothers at the age of seven or eight. At age 17 they began stalking animals in the deep forest all on their own at 17. A good hunter was respected by all and young women wanted to marry him. Horses were indispensable to the Oroqens on their hunting expeditions. Hunters rode on horses, which also carried r family belongings and provisions as well as the game they killed over mountains and across marshes and rivers. The Oroqen horse is a very sturdy breed with extra-large hooves that prevent the animal from sinking into marshland and snow. |

Oroqen hunters relied on dogs and shotguns and used horses obtained from the Manchus and Mongols. They hunted year round, going after furs in the winter, deer with antlers in May and June and deer for venison and male organs in September. Hunters wore animal skins clothes and wore hats made from the head of a deer or other animals. They also engaged in some fishing and collecting.[Source: Liu Xingwu,“Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 6: Russia-Eurasia/China” edited by Paul Friedrich and Norma Diamond, 1994 |~|]

Collective hunting was normally organized within traditional regional communes called wulilengs. Hunters traditionally worked in groups of three to five, called anag, led by a tatanda, who was usually the most senior member in the group, with the most hunting experience.. Meat was shared equally, with special care taken to make sure the sick, aged and disabled were provided for. The hunters usually cooked and ate the internal organs and head together. Women sometimes hunted and fished but usually they were responsible for drying the meat and tanning hides.

The Oroqen no longer rely on hunting but hunters south of the Amur River still brave -30̊F temperatures in the winter to track deer and moose. The winter was often the best time to hunt because animals could be easily located by following their tracks in the snow. An 83-year-old former Oroqen leader named Baiyaertu told Time magazine in 2008. “Hunting is good. It’s good for the body. After you came back with something, you feel really happy...In the past there was no road, no railroad. There were no Han people. There was nobody here. You could see deer, roe deer, everything. Now there are people here, and the animals have all gone.” Because of a scarcity of game the Chinese government outlawed hunting in the Oroqen banner in 1996. While some hunt in Heilongjiang Province where hunting is allowed and poach in the mountains hunting as a way of life has vanished.

Excerpt The Last Quarter of the Moon

Chi Zijian wrote: “The birth of a literary work resembles the growth of a tree. It requires favorable circumstances. Firstly, there must be a seed, the Mother of All Things. Secondly, it cannot lack for soil, nor can it make do without the sunlight’s warmth, the rain’s moisture or the wind’s caress.In the case of The Last Quarter of the Moon, however, first there was soil, and only then was there a seed. For this land that turns muddy as the ice thaws in the spring, shaded by green trees in the summer and covered by motley leaves in the autumn and endless snow-white in the winter, is very familiar to me. “[Written for the GLLI – Paper Republic collaboration, February, 2017]

“After all, I was born and raised on this land. As a child entering the mountains to fetch firewood, more than once I discovered an odd head-shape on a thick tree trunk. Father told me that was the image of the Mountain Spirit Bainacha, carved by the Oroqen. I knew the Oroqen were an ethnic minority who lived on the outskirts of our mountain town. They resided in their open-top cuoluozi (teepees) where they could spy the stars at night. In the summer they fished in their birch-bark canoes, and in the winter they hunted in the mountains wearing their parka and roe-deerskin boots. They liked to go horse riding, drink liquor and sing songs. In that vast and frigid land, their small tribe was like a pristine spring trickling deep in the mountains. Full of vitality, yet solitary.

“I once believed that the masses of forestry workers, those loggers, were the genuine masters of the land, while the Oroqen in their animal hides were aliens from another galaxy. Only later did I learn that before the Han came to the Greater Khingan Range, the Oroqen had long lived and multiplied on that frozen land. Dubbed the “green treasure house,” the forest grew thick and animals abounded before it was exploited. There were very few roads and no railroad. Most paths in the wooded mountains were trodden by the nomadic hunting peoples, the Oroqen and the Evenki.

“After large-scale exploitation of the forest began in the sixties, bevies of loggers were stationed in the forest and one road after another — for timber transport — appeared, along with railroad tracks. Whizzing along those roads and tracks each day were trucks and trains laden with logs bound for destinations beyond the mountains. The sound of trees falling displaced birdcalls, and chimney smoke displaced clouds. In reality, the exploitation of nature is not wrong; when God left man to fend for himself in the mortal world, wasn’t it to force him to find the answer to survival within Nature? The problem is, God wished us to seek a harmonious form of survival, not a rapacious, destructive one.

“One, two, three decades passed, and the sound of tree felling quieted but didn’t cease. Continuous exploitation and certain irresponsible, reckless actions made the virgin forest begin to display signs of aging and decline. Like an apparition, dust storms suddenly appeared at the dawn of the new century. At last, the sparse tree coverage and decimated animal population alerted us: We have exacted too much from Mother Nature! It is the hunting peoples living in the mountain forests who have suffered the most grievously. Specifically, I mean those we call the “Last of the Nomadic Hunters”: the reindeer-herding Aoluguya Evenki.

Image Sources: Nolls China website, Donsmaps, University of Washington, San Francisco Museum, CNTO

Text Sources: 1) "Encyclopedia of World Cultures: Russia and Eurasia/ China", edited by Paul Friedrich and Norma Diamond (C.K. Hall & Company; 2) Liu Jun, Museum of Nationalities, Central University for Nationalities, Science of China, China virtual museums, Computer Network Information Center of Chinese Academy of Sciences, kepu.net.cn ~; 3) Ethnic China *\; 4) Chinatravel.com \=/; 5) China.org, the Chinese government news site china.org | New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Lonely Planet Guides, Library of Congress, Chinese government, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, Reuters, AP, AFP, Wikipedia, BBC and various books, websites and other publications.

Last updated October 2022