EWENKI

Ewenki diorama

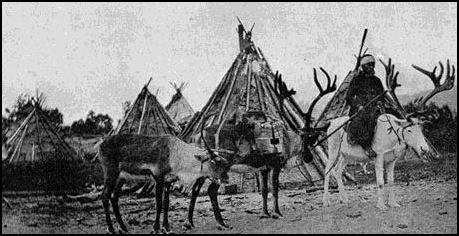

The Ewenki are a small ethnic minority that live in northern Heilongjiang Province and eastern Inner Mongolia. Closely related to the Tungus, Evenski and Yakut in Siberia and more distantly related to Kazakhs and Kyrgyz, they are a Turkic people who originated from the Lake Baikal region of Russia. They speak Tungus-Manchu languages, look like Mongolians and have traditionally herded reindeer, traded furs and hunted and fished. Many Ewenki migrated to northern China from the Lena River Valley in Siberia beginning in the mid 17th century. Reindeer were used mainly to haul tepees and bedrolls on long expeditions to hunt for moose, bear and wild boar. [Source:Liu Xingwu, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 6: Russia-Eurasia/China” edited by Paul Friedrich and Norma Diamond, 1994 |~|]

Ewenki (pronounced ee-WEHN-kee) are also known as the Tungus (Tongusi), Sulun (Suolun), Yakut (Yakute) and Kamonikan; . Some regard them as members of the Tungus group, which lives in Siberia and includes the Evenks. In China, they have traditionally been grouped with the Oroqens and Dauers, who were collectively referred to as the ‘Sulun Tribes,” and have been ruled by Manchus, Russians, Japanese and Chinese. Since the Communists have come to power many have given up their traditional ways. Few herd reindeer anymore. Most Ewenki are engaged in farming, farm-herding or animal husbandry. A few live as their ancestors did, as roving hunters and reindeer herders, in the forests around the Greater Xingan Mountains.

'Ewenki' is the name used by the Ewenki to describe themselves. It means “folks living in mountain forests” or "people living in the big mountain". Ewenki people used to live in the forest north of Lake Baikal and later moved east to the middle reaches of Heilong Jiang (Amur River). In the past, the Ewenki were known as the 'Suolun', 'Tonggusi' and 'Yakute'—the names of different Ewenki groups that lived separately from one another. The joint name 'Ewenki' did not emerge as a widely used name until 1957.

Websites: 1) Northern Hunting Culture has pictures of the Aoluguya Evenki, their lifestyle and handicrafts.

See Separate Article EWENKI LIFE AND CULTURE factsanddetails.com ; EVENKI AND EVEN factsanddetails.com ; REINDEER factsanddetails.com REINDEER AND PEOPLE factsanddetails.com; ETHNIC GROUPS IN NORTHERN CHINA factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: “Ecological Migrants: The Relocation of China's Ewenki Reindeer Herders” by Yuanyuan Xie Amazon.com; “Reclaiming the Forest: The Ewenki Reindeer Herders of Aoluguya” by Åshild Kolås and Yuanyuan Xie Amazon.com; The Fire God Festival of the Ewenki Ethnic Group (Bilingual Version of English and Chinese) by Yan Xiangjun and Pi Xuan Amazon.com; “The Moose of Ewenki” (Children’s Book) by Gerelchimeg Blackcrane, Jiu Er, Helen Mixter Amazon.com; “The Ewenki Dialects of Buryatia and Their Relationship to Khamnigan Mongol (Tunguso-Sibirica) by Bayarma Khabtagaeva Amazon.com; “Reindeer Herders in My Heart: Stories of Healing Journeys in Mongolia” by Sas Carey (Author) Amazon.com; “The Minorities of Northern China: A Survey” by Henry G. Schwarz (1984) Amazon.com; “On the Edge: Life along the Russia-China Border” by Franck Billé and Caroline Humphrey Amazon.com; “Evenki (Languages of the World) by N. I A Bulatova Amazon.com; “Evenki Economy in the Central Siberian Taiga at the Turn of the 20th Century: Principles of Land Use” by Mikhail G. Turov, Andrzej W. Weber, et al. Amazon.com; “Katanga Evenkis in the 20th Century and the Ordering of their Life-World” by Anna A. Sirina, David G. Anderson, et al. Amazon.com; “Shamanism in Siberia: Animism and Nature Worship: The Shaman Spirit of Buryat, Altai, Yakut, Tuvan, Evenki, Sakha, Chukchi, Dolgan, Khanty, Mansi, Amazon.com; “The Flying Tiger: Women Shamans and Storytellers of the Amur” by Kira Van Deusen Amazon.com

Ewenki Language

The Ewenki-Evenk language belongs to the Manchu-Tungusic family of languages. There are three dialects — 1) River Hui and Yimin (Buteha), 2) River Moerge (Chenbaerhu) and 3) Aoluguya (Erguna). Mongolian is the language generally used in pasturing areas, and Chinese is the language generally used in agricultural and mountainous areas. Ewenki has no writing system. Ewenki children are educated in schools set up in pastoral areas. Schools use the Han Chinese and Mongolian language, both oral and written.

Where the Ewenki live

Tungusic languages (also known as Manchu-Tungus and Tungus) are spoken in Eastern Siberia and Manchuria by Tungusic peoples. Many Tungusic languages are endangered. There are approximately 75,000 native speakers of the dozen or so living Tungusic languages.Some linguists consider Tungusic to be part of the controversial Altaic language family, along with Turkic, Mongolic, and sometimes Koreanic and Japonic. The term "Tungusic" is from an exonym for the Evenk(Ewenki) and people used by the Yakuts ("tongus"). It was borrowed into Russian and ultimately transliterated into English as "Tungus". [Source: Wikipedia]

The Evenki language is spoken by several tens of thousands of Evenki in China, Russia and Mongolia. Bruce Hume wrote on Ethnic China Lit: According to an expert cited in Wikipedia (Evenki Language), in Russia, ‘since the 1930s “folklore, novels, poetry, numerous translations from Russian and other languages, textbooks, and dictionaries have all been written in Evenki.” Evenki elementary and middle school textbooks have also been published.

“As I understand it, however, nothing similar has taken place on the Chinese side of the border. In my piece on Evenki Place Names Behind the Hànzì, I describe how related research is carried out in the PRC: Indeed, a book called “Evenki Place Names,” compiled by a committee of Evenki scholars in 2007, confirms that those [Evenki place] names [cited in a novel about the Evenki, Last Quarter of the Moon] definitely exist. This book alone cites some 1,800 Evenki place names, and the overwhelming majority are not translations from the Chinese, although many have been influenced by Russian, Mongolian and Manchu names.

“As might be expected in politically correct China today, the book cites only those place names that are located within the People’s Republic of China. Considering that the Evenki traditional homeland extended into Russia, that’s an annoying blind spot! I have found the same approach in other Evenki-related reference works written and published in China. For instance, “Evenki: A Reference Grammar”, by the respected Evenki scholar Dr. Chao Ke who earned his doctorate in Japan, is a 365-page tome which mentions that about half of all Evenki live in Russia, and speak a dialect that differs somewhat from those spoken in China. Period. There is no further discussion of how this dialect has been impacted by contact with a Slavic language, for instance, or how it otherwise differs from those spoken on the Chinese side of the border.

Ewenki Population and the Region Where They Live

The Ewenki are the 41st largest ethnic group and the 40th largest minority out of 55 in China. They numbered 30,875 in 2010 and made up less than 0.01 percent of the total population of China in 2010 according to the 2010 Chinese census. Ewenki populations in China in the past: 30,545 in 2000 according to the 2000 Chinese census; 26,315 in 1990 according to the 1990 Chinese census. A total of 4,957 were counted in 1953; 9,681 were counted in 1964; and 19,440 were, in 1982.

Ewenki are regarded as part of the Evenks group in China and eastern Russia and Siberia. The total Evenks population is 69,856, with 37,843 in Russia, 30,875 in China, 537 in Mongolia and 48 in Ukraine. [Sources: People’s Republic of China censuses, Wikipedia]

The Ewenki are distributed across seven banners (counties) in the Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region and in Nahe County of Heilongjiang Province. Most reside in Ewenki Autonomous Banner, Hulunbei'er city in the Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region. Others are found in Chenba'erhu District, Erguna Zuo district, Molidawa District , Arong District, Zhalantun City, and Nehe County in Heilongjiang province. They usually live in these places alongside members of the Mongolian ethnic minority, Han Chinese and the Oroqen ethnic minority group.[Source: Liu Jun, Museum of Nationalities, Central University for Nationalities, Science of China, China virtual museums, Computer Network Information Center of Chinese Academy of Sciences]

The Ewenki have traditionally lived in the hills of a branch range of the Da Xing'an Mountains. According to China Ethnic Groups: "Known as the last hunting tribe of China, Ewenki people had lived of hunting and raising reindeer deep in the Greater Hingan Mountain for generations"- Their homeland is a region of grasslands, dense virgin forests, rivers and lakes and lots of game and fish. Ewenki living in different areas lead different lives. Those who inhabited the Ewenki autonomous district and the Chenba'erhu district traditionally lead a stockbreeding life; those in Nehe County were farmers; those in Molidawa and Arong Districts and Zhalantun City were hunters and farmers; and those who inhabited the Ewenki village of Aoluguya in Erguna Zuo District lead a traditional life of hunting. Since reindeer were vital to living the nomadic, hunting, life they were called “the reindeer-using Ewenki”.

Ewenki Autonomous Banner

The Ewenki Autonomous Banner, nestled in the ranges of the Greater Hinggan Mountains, is where the Ewenkis live in compact communities. A total of 19,110 square kilometers in area, it is a hilly grassland with more than 600 lakes, 11 springs and a large number of rivers flowing in different directions. . The pastureland here totaling 9,200 square kilometers is watered by the Yimin and four other rivers, all rising in the Greater Hinggan Mountains. Nantunzhen, the seat of the banner government, is a rising city on the grassland. A communication hub, it is the political, economic and cultural center of the Ewenki Autonomous Banner. Under the influence of the Siberian winds, the climate is severe, with a long snowy winter and virtually no summer. [Source: China.org |]

Large numbers of livestock and great quantities of knitting wool, milk, wool-tops and casings are produced in the banner. The yellow oxen bred on the grassland have made a name for themselves in Southeast Asian countries. Pelts of a score or so of fur-bearing animals are also produced locally. Reeds grow in great abundance along the Huihe River in the banner. Some 35,000 tons are used annually for making paper. Lying beneath the grassland are rich deposits of coal, iron, gold, copper and rock crystal. |

See Separate Articles: HEILONGJIANG AND THE AMUR: THEIR HISTORY, SIGHTS AND ETHNIC MINORITIES factsanddetails.com ; INNER MONGOLIA: ITS STEPPES, ETHNIC GROUPS AND NEOLITHIC CULTURES factsanddetails.com

Origin of the Ewenki and Oroqen

The ancestors of the Ewenki and Oroqen and other groups lived in the forests northeast of Lake Baikal and in the forest bordering the Shilka River (upper reaches of the Heilong River). They survived by hunting, fishing, and raising reindeer. Historically they were often grouped together with Oroqens and Daurs, who share much of their cultural tradition, and referred to as the “Sulun Tribes."

The forefathers of the Ewenkis trace their ancestry to the "Shiweis", particularly the ""Bei Shiwei" (Northern Shiweis") and "Bo Shiweis" living at the time of Northern Wei (386-534) on the upper reaches of the Heilong River, and the "Ju" tribes that bred deer at the time of the Tang Dynasty (618-907) in the forests of Taiyuan to the northeast of Lake Baikal. The Shiwei were a Mongolic people that inhabited far-eastern Mongolia, northern Inner Mongolia, northern Manchuria and the area near the Okhotsk Sea. The oldest records mentioning the Shiwei date to the time of the Northern Wei (386-534). The term Shiwei remained until the rise of the Mongols under Genghis Khan in 1206 when the name "Mongol" and "Tatar" were applied to all the Shiwei tribes. The Shiwei-Mongols were closely related to the Khitan people to their south.

During the Tang Dynasty (618–907), Imperial China set up a government office in the area where the ancestors of Ewenki lived. Before the Mongol era the tribed that gave birth to the Ewenki migrated east, with one group making its home on the middle reaches of the Heilong River. During the Yuan Dynasty (1280-1368) the Ewenkis, Oroqens and Mongolians living in forests to the east of Lake Baikal and the Heilong River Valley were known as a "forest people." In the Ming Dynasty they were called “the northern mountains deer riding people."

Ewenki History

Ewenki-like tribes in the 1860s

Between 1633 and 1640, the Manchus of northeast China conquered the people who became the Ewenkis. After the Manchu took over all of China, the Ewenki were organized by the Manchu into zuos, administrative units based on clan organization and required to pay marten fur tributes. After the mid-17th century, the Qing moved the Ewenki to the Nen River Valley, close to the Greater Xing'an Mountains after czarist Russia invaded Manchu territory. In 1732, the Imperial Chinese government ordered 1,600 “Kamonikan" soldiers to go to a military post in the Hulunbeir grassland of present-day Mongolia. They brought their wives and children and settled there, and formed into a group that was later given the name Ewenki by the Chinese. [Source: C. Le Blanc, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009]

In the Qing period (1644-1911) the people that became the Ewenki belonged to two groups: the "Sulongs" and the "Kemunikans". In 1635, the Kemunikans came under the domination of Manchu rulers after their conquest of the Lake Baikal area, to be followed around the years from 1639 to 1640 by their control of the Sulongs living to the east of Lake Baikal. From the mid-17th century onwards, aggression by Tsarist Russia had led the Qing government to remove the Ewenkis to the area along the Ganhe, Nuomin, Ahlun, Jiqin, Yalu and Namoer — tributaries of the Nenjiang River. In 1732, 1,600 Ewenkis were called up in the Buteha area and ordered together with their family dependents to perform garrison duties as frontier guards on the Hulunbuir Grassland. Their descendants are now the inhabitants of the Ewenki Autonomous Banner. [Source: China.org |]

With the institution of the "eight banner system" way back in the 17th century, Ewenki nomads were drafted into the army and had the obligation to pay leopard skins as tributes to the Qing rulers. A "nimoer" mutual-aid group consisting of a few to 10-odd families was usually formed by the Ewenkis to pasture their herds. People in the group were members of the same clan. Immigrations in the past led to population dispersion which in turn resulted in great unevenness in the social development of the Ewenki people dwelling in different places with diverse natural conditions. As a result, some Ewenkis have traditionally been nomads; others are farmers or farmer-hunters. A small number of them were hunters. The Ewenkis in the Ewenki Autonomous Banner and the Chenbaerfu Banner led a nomadic life, wandering with their herds from place to place in search of grass and water. They lived in yurts. |

In the forests of the Ergunazuo Banner Ewenki hunters had no permanent homes and wandered from place to place with their reindeer in search of game. When they stopped these Ewenki hunters lived in teepee-like tents built on 25 to 30 larch poles. In summer these tents were roofed over with birch bark, and in winter with reindeer hides. When the hunters were on the move, their tents and belongings as well as their capture were carried by reindeer, which lived on moss. Five or six to a dozen families who were very closely related were grouped in a clan. All members of the clan took part in hunting, and the game bagged was divided equally among the families. Shot-guns, reindeer and animal pelts were valued. |

At the end of the nineteenth century the Ewenki were part of the Boxer Rebellion, and later they played an important role in the anti-Japanese war in the 1930s and 40s. Wars, diseases and other hardships decimated their population. After the founding of the People's Republic, the government of China carried out a policy of social reform and economic development; the Ewenki were gradually integrated into the national efforts for modernization.

Reindeer-carried tents

Ewenki in the 19th Century

Describing Tungus in the 1820s, the explorer John Bell wrote: "They have no homes where they remain for any time, but range throughout the woods and long rivers for pleasure; and, wherever they come, they erect a few spars, in clinging to one another at the top; these they cover with pieces of boiled birch bark, sewed together, leaving, a hole at the top to let out smoke.

"They can not bear to sleep in a warm room, but retire to their huts and lie about the fire on skins of wild bears. It is surprising that these creatures can suffer the very piercing cold of these parts,"

"They are very civil and tractable, and like to smoke tobacco and drink brandy...I have seen many of the men with oval figures, like wreaths, on their foreheads and chins...These are made, in their infancy, by pricking the parts with needles and rubbing them with charcoal...They have many shamans among them, I was told of others, whose abilities for fortune-telling far exceeded those of the shaman."

"The women dressed in a fur-gown, reaching below the knee, and tied about the waist with a girdle...made of deer skins, having their hair curiously stitched down and ornamented...The dress of the men consists of a short jacket with narrow sleeves made of deer skin, having the fur outward; trousers and hoses of the same kind of skin...They have besides a piece of fur, that covers the breasts and stomach, which is hung about the neck with a string of leather."

"Their arms are a bow and several sorts of arrows, according to the different kinds of game they intend to hunt...In winter, the season for hunting wild beasts, they travel on what are called snow shoes...They have a different kind of shoe for ascending hills, with the skins of seal glued to the boards, having the hair inclined backwards which prevents them from sliding on there shoes...When a Tungsu goes hunting into the woods, he carries with him no provisions, but depends entirely on what he has to catch."

Near Extinction, Development and Settling of the Ewenki

Dispersed to live in different places and with many Ewenkis dragged into the army by the Qing rulers, the Ewenki ethnic group was threatened by extinction. Of a total number of 1,700 Ewenki troops sent to suppress a peasant army of other nationalities that rose against the Qing government in 1695, only some 300 survived the fighting. Following their occupation of northeast China in 1931, the Japanese drafted many Ewenki of them into the Japanese army. This, coupled with the spread of smallpox, typhoid fever and venereal diseases, brought about a sharp population decline. For example, there were upwards of 3,000 Ewenkis living along the Huihe River in 1931, but less than 1,000 remained in 1945. [Source: China.org |]

diorama of grasslands of Ewenki

After the Communists came to power in 1949, reforms were carried out in both the pastoral and farming areas. As for Ewenki hunters roving in the forests, efforts were made to help them develop production by setting up cooperatives. Socialist reforms in most of the Ewenki area were completed towards the end of 1958. The Ewenki Autonomous Banner was established on August 1, 1958, in the Hulun Beir League (Prefecture). Five Ewenki townships and an Ewenki district were set up later. A large number of Ewenkis were trained for administrative work. |

A series of measures, including the introduction of fine breeds of cattle, the opening of fodder farms, improved veterinary services, the building of permanent housing for nomads and the use of machinery have boosted livestock production in the Ewenki Autonomous Banner but compromised teir traditional way of life. In the forested areas, Ewenki hunters, who used to be on the move after their game, now live in permanent homes. They still hunt, but they have also gone in for other occupations. |

In the old days almost all the Ewenkis were illiterate. Today more than 90 per cent of all school-age children are at school. Some Ewenkis have been enrolled in the Central Nationalities Institute in Beijing, Inner Mongolia University in Hohhot and other institutions of higher learning. With improved health care tuberculosis and other diseases that used to plague the Ewenki people have been put under control. Hospitals, maternity and child care centers, tuberculosis and venereal disease prevention clinics are now at the service of the Ewenkis. As a result the population in the banner, which had dwindled for a century or more, has increased by many folds in recent decades. |

Ewenki Religion and Funerals

Some Ewenki have adopted Tibetan Buddhism but have traditionally been animists, worshiping many natural elements, including a wind god, mountain god and fire god. Ancestor worship has also been practiced. Ewenki who inhabited pasturing areas alongside Mongolians adopted Tibetan Buddhism. A few living in the Chenbaerhu area are believers of the Eastern Orthodox Church. An aobao is a pile of stones or earth regarded as the dwelling place of a god and where sacrifices were offered. See Aobao Festival Below. [Source: "Encyclopedia of World Cultures: Russia and Eurasia/ China", edited by Paul Friedrich and Norma Diamond (C.K. Hall & Company, 1994)]

museum Ewenki shaman

Shaman have traditionally been consulted for spiritual matters and health problems. The shaman can be men or women. Usually the became shaman after a long illness and accept no payment for their services. Ewenki shamans were highly respected. Among the Ewenki in Ergun Banner, the clan chief is often a shaman. The Ewenki have traditionally relied on shamans to cure the sick along with certain herbs and internal organs of animals.

In the old days, the Ewenki practiced wind burial, in which the bones of the dead were hung in a hollow tree suspended on tree stumps. Under the influence of the Russian Orthodox Church, they have mostly abandoned that custom and now practice mostly earth burials. With a wind burial, the corpse was placed in a coffin, or wrapped with bark or willow twigs and then hung high in a tree, put into a hollowed-out tree trunk or put on a two-meter high suppor in the forest with head pointing south. The blowing of the wind, drenching of the rain, scorching of the sun, and beaming of the moon were believed to transform the dead into a star. Sometimes the horse of the deceased is killed to accompany the departing soul to netherworld. Only the bodies of young people who die of contagious diseases are cremated. [Source: China.org |]

Traditional Ewenki Religion

The traditional Ewenki beliefs are rooted in shamanism (the belief in good and evil spirits that can be influenced by the shaman or holy person) and totemism (the practice of having animals or natural objects as personal and clan symbols). Ewenki religion stresses the worship of ancestors, animals, and nature. Special rituals are performed for Jiya (the livestock god), and fire. Fire should never be allowed to die out, even when Ewenki families migrate. [Source: C. Le Blanc, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009 ++]

Bears and some birds are revered and prayed to for good weather and hunting. The swan is an important totemic animal. Bears are sacred animals protected by hunting taboos. Traditionally, whenever the Ewenki ate bear meat they conducted the same rituals they did for their own dead. The lingering influences of bear worship is still found among Ewenki hunters. After killing a bear, the Ewenkis would conduct a series of rituals at which the bear's head, bones and entrails are bundled in birch bark or dry grass and hung on a tree to give the beast a "wind burial." The hunters weep and kowtow while making offerings of tobacco to the dead animal. [Source: China.org |]

Special rituals are performed for Jiya (the livestock god) and fire. Fire should never be allowed to die out, even when Ewenki families are on the move. te. In the Chenbaerhu area every clan has its own totem — usually a bird such as a swan, eagle or a duck — as an object of veneration. People toss milk into the air upon seeing a real swan or duck flying overhead. Killing or doing harm to a bird is considered taboo, especially if the bird is one's own totem. ++

Reverence for fire See Customs Under EWENKI LIFE AND CULTURE factsanddetails.com

Excerpt on Shamanism from Last Quarter Moon

spirit tree

In a fictional account of Ewenki shamanism, Chi Zijian wrote in “Last Quarter of the Moon”: The grass grew green, flowers bloomed, swallows flew back from the south, and the waves shimmered again on the river. The ceremony marking Nihau’s designation as our clan’s Shaman was set to take place amidst the sights and sounds of springtime. According to established practice, a new Shaman’s initiation should take place at the urireng of the former Shaman. But Nihau was pregnant again, and Luni was worried that it would be hard for her to travel to Nidu the Shaman’s old urireng, so Ivan invited a Shaman from another clan to come and preside over the Initiation Rite. [Source: Chi Zijian, “Last Quarter of the Moon”, ethnic-china.com]

“She was known as Jiele the Shaman. Past seventy, she still had a straight back, a set of neatly spaced teeth and a head of jet-black hair. Her voice carried far, and even after downing three bowls of baijiu without a pause her gaze didn’t waver. We erected two Fire Pillars to the north of our shirangju, a birch tree on the left, a pine on the right, symbolising the co-existence of mankind and the Spirits. They had to be big trees. In front of them we also placed two saplings – once again, a birch on the left and a pine on the right. We stretched a leather strap between the two big trees, and attached sacrificial offerings – reindeer hearts, tongues, livers and lungs – to show reverence to the Shaman Spirit. Blood from a reindeer heart was smeared onto the saplings. Besides all this, Jiele the Shaman hung a wooden sun to the east of the shirangju, and a moon to the west. She also carved a wild goose and a cuckoo out of wood, and suspended them separately.

“The Spirit Dance Ceremony commenced. Everyone in our urireng sat next to the blazing fire observing Jiele the Shaman as she taught Nihau the Spirit Dance. Nihau was wearing the Spirit Robe left behind by Nidu the Shaman, but Jiele the Shaman had adapted it because he had been fat and taller than Nihau, so the Spirit Robe was too loose for her. That day it seemed that Nihau was a bride again. Clothed in a Shaman’s costume, she was lovely and dignified. Attached to the Spirit Robe were small wooden replicas of the human spine, seven metal strips symbolising human ribs, and lightning bolts and bronze mirrors of every size. The shawl draped on her shoulders was even more resplendent with teal, fish, swan and cuckoo bird adornments fastened to it. Twelve colourful ribbons symbolising the twelve Earthly Branches hung from the Spirit Skirt she wore, and it was also embellished with myriad strings of tiny bronze bells.

“The Spirit Headdress she donned resembled a large birch- bark bowl covering the back of her head. Behind it draped a short, rectangular ‘skirt,’ and at the top rose a pair of small bronze reindeer antlers. Several red, yellow and blue ribbons were suspended from the branches, symbolising a rainbow. In front of the Spirit Headdress dangled strands of red silk that reached the bridge of her nose, endowing her gaze with a mysterious air, since her eyes were visible only via the gaps between the strands of silk. As Jiele the Shaman had instructed her, before the Spirit Dance Nihau first addressed a few words to the entire urireng. She proclaimed that after she became a Shaman she would unquestionably use her own life and the abilities bestowed upon her by the Spirits to protect our clan, and ensure that our clansmen would multiply, our reindeer teem, and the fruits of our hunting abound year after year.

“With her left hand holding the Spirit Drum and her right hand grasping the drumstick made from the leg of a roe-deer, she followed Jiele the Shaman and began her Spirit Dance. Although Jiele the Shaman was very elderly, as she began to perform the Spirit Dance she was full of energy. When she beat the Spirit Drum, birds came flying from afar and alighted on the trees in our camp. The drumbeat and the chirping of the birds blended poignantly. That was the most glorious sound I’ve heard in my life.

“Nihau danced with Jiele the Shaman without pause from high noon until the sky went dark. Luni lovingly brought Nihau a bowl of water to get her to take a sip, but she didn’t even glance at it. Meanwhile, the rhythm of Nihau’s drumbeats grew more compelling, and her dancing more skillful and eye- catching with every step.Jiele the Shaman stayed in our camp for three days and danced the Spirit Dance each day, and she used her drumming and dancing to transform Nihau into a Shaman.”

Ewenki Festivals

The major Ewenki festivals are the Aobao Gathering, Spring Festival and Mikuole Festival. In agricultural areas, the festivals of the Ewenki are so different from those of the Han Chinese. In pastoral areas, the Aobao Gathering and the Mikuole Festival are more widely celebrated. Like the Han Chinese and most ethnic groups in China, the Ewenki celebrate the Spring Festival (Lunar New Year, Chinese New Year) between January 21 and February 20 on the ; Western calendar. The Aomi Naneng Festival is a festival held in the eighth lunar month in the fall in the pasturing area. Huge celebrations of religious activities and entertainments are held. [Source: C. Le Blanc, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009, China.org, Chinatravel.com]

The Aobao Gathering is one of the most important Ewenki festivals. Held in the summer during sixth or seventh lunar month (between June 22 and August 21 on the Western calendar), the festival includes popular sporting events, such as wrestling, horse racing and pushing and pulling. Oxen, goats and sheep are slaughtered as sacrificial offerings to honor the Aobao God and to pray for safety and health and favorable weather for crops. Aobao is a Mongolian term meaning “a pile".

An Aobao is a pyramidal pile of stones, mud bricks, earth or grass, flanked by a certain number of poles from which multicolored silk streamers are flown. Some streamers are covered with sacred Buddhist inscriptions. The Aobao is regarded as the dwelling of God in shamanism. In some areas, the Aoboa is a large tree, called the Aobao tree. Traditionally, Mongolians and other ethnic groups in northeastern China used aoboa as road or boundary markers and because it the dwelling place of a god sacrifices were offered.

Mikuolu Festival

The Mikuolu Festival is essentially a livestock fair. Regarded as a special occasion to see old friends and gather at feasts, it is held in the last ten days of lunar fifth lunar month (between June 11 and July 21 on the Western calendar). Men, women and children gather in the grasslands and enjoy wine, fine foods and other delicacies prepared for the occasion. It is a time for nomads to count new-born lambs and cattle, celebrate the harvest and take stock of their wealth. Young, sturdy lads demonstrate their skills in lassoing horses and branding or castrating them. Horses are branded and their manes are cut and sheep's ears are incised with the owner's mark.

"Mikuolu" is the most festive day of the year for the pasture Ewenki. People dress up in beautiful national dress. Relatives and friends get together to castrate and brand the animals. Strong and vigorous young men, on horseback, chase and lasso fierce, two-year-old horses. When the horses are lassoed, riders jump on the horse. Some draw its tail and some seize its ears. They hurl the horse to the ground, Some cut its mane, some cut the end of the tail and some make a brand. The owner of the horse is branded on the right side of a hinder leg. The whole process is very tense, exiting and interesting labor, as well as a good chance for Ewenki riders to compete with each other and show their riding skills. [Source: Liu Jun, Museum of Nationalities, Central University for Nationalities, Science of China ~]

Traditionally, when the Ewenki are castrating and branding sheep, the old give children female lambs as gifts, with a blessing of prolificacy and happiness. After all the work is done, a chief or group leader hosts a feast for relatives and friends. The number of newly born cattle and sheep are declared. When the feast of one household finishes, people rush to another house for a feast there. ~

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, Donsmaps, University of Washington

Text Sources: 1) "Encyclopedia of World Cultures: Russia and Eurasia/ China", edited by Paul Friedrich and Norma Diamond (C.K. Hall & Company; 2) Liu Jun, Museum of Nationalities, Central University for Nationalities, Science of China, China virtual museums, Computer Network Information Center of Chinese Academy of Sciences, kepu.net.cn ~; 3) Ethnic China *\; 4) Chinatravel.com \=/; 5) China.org, the Chinese government news site china.org | New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Lonely Planet Guides, Library of Congress, Chinese government, The Guardian, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, The New Yorker, Reuters, AP, AFP, Wikipedia, BBC and various books, websites and other publications.

Last updated October 2022