CHINGLISH

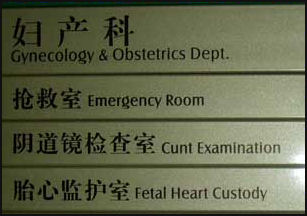

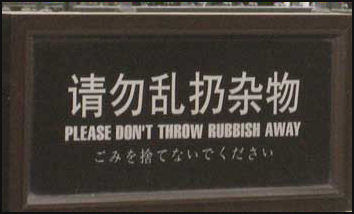

Amusing "Chinglish" or "fractured English" expression observed in China include "Let's Joy," "Be careful not to be stolen," and "shoplifter will be fined ten times." In hotels there are signs that read “Please Take Advantage of the Chambermaids.” On the highway drivers are warned of slippery conditions with the sign: “the slippery are very craftily.” Restaurant menus are filled with mistakes. One offers “fried rice with crap” rather than crab and “chop the strange fish” Others offer “worm pig stomach,” “corrugated iron beef” and “cow bowel in sauce.”

A sign at the Park of Ethnic Minorities in Beijing reads “Racist Park.” Signs on emergency exits at Beijing international airport inform people: “No entry in peacetime.” In Shenzhen people wear T-shirts that read “What the Wish Are Blackwore” and “Bizarre Must Awesome Want.” In preparation of the Beijing Olympics one restaurant ran its name through a translation website and put the result above the door: “TRANSLATE SERVER ERROR.”

According to Lonely Planet, bathroom signs which read "Please don't take the odds and ends put into the nightstool" means "don't drop any cigarette butts or trash into the toilet"; "Question authority" really means "address your questions to the government official"; and "Don't stoke the works" means "Don't touch."

An article in the English-language China Daily supporting government efforts to purge foreign words from the Chinese language, read: "names containing vulgar, feudalist, bizarre and absurd content and Western-sounding color must be banned...They could have an adverse effect on our children." Officers with the Beijing Speaks Foreign Languages Program give out dialogues to workers and fine businesses that hang signs with goofy “Chinglish” phrases.

English-inspired slang expressions include “my ga” ("My God") and “ku” ("cool"). Among some of the new words that have entered China in recent years are “fang nu” (“house slave”) — homeowners stuck with debilitating mortgages payments — and “ban tang fu qi” (“semi-honey couples”) — couples that live in separate houses to keep their romance alive — and “duan bel” (“brokeback”) — male homosexual — and “ding chong” jia ting (DINK with pets) — double income, no kids with pets.

Sometimes they appear to be trying to say something philosophical. A sign at a building site warned “construction to cause inconvenience to your understanding.” A sign at a nation park read: “Cherish monkeys at the moment of entertainment, which are good friends of mankind.” [Source: Times of London]

A sign in Hainan reads: “Do not disturb — tiny grass dreaming.” One at a dentist office asked patients to “not scream.” One outside an elevator prohibited ‘smoking or joking.” Actor Jackie Chan promotes “anti-falling shampoo.” [Source: Times of London]

Websites and Sources: Chinglish Chinglish Files chinglish.de Chinese English.com Chinglish Archives chineseenglish.com ; Links in this Website: CHINESE LANGUAGE TYPEWRITERS AND TATTOOS factsanddetails.com ; CHINESE SAYINGS, PROVERBS, PUNS AND SLOGANS factsanddetails.com ; ENGLISH IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; CHINGLISH AND CRAZY ENGLISH IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; CHINESE NAMES factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: “Chinglish: Found in Translation” by Oliver Lutz Amazon.com; “Plain Chinglish” by Oliver Radtke Lutz Amazon.com; “More Chinglish: Speaking in Tongues (English and Chinese Edition)” by Oliver Lutz Radtke Amazon.com “Teaching English in China” by Michael Pollock Amazon.com; “Crazy English: An Ethnography Examining the Fascination with English in Contemporary China” by Arion Thiboumery (2009) Amazon.com; “Teaching in China: A Snapshot of Working in the Middle Kingdom” by Stephen Johnson Amazon.com

Mangled English in Shanghai

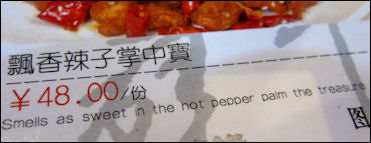

Andrew Jacobs of the New York Times wrote that in Shanghai, “There are banks with machines for cash withdrawing and cash recycling. The menus of local restaurants might present such delectables as fried enema, monolithic tree mushroom stem squid and a mysterious thirst-quencher known as The Jew’s Ear Juice. Those who have had a bit too much monolithic tree mushroom stem squid could find themselves requiring roomier attire: extra-large sizes sometimes come in fatso or lard bucket categories. These and other fashions can be had at the clothing chain known as Scat.” [Source: Andrew Jacobs, New York Times, May 2, 2010]

These managed to slip through despite effort the Shanghai Commission for the Management of Language army of 600 volunteers and a politburo of adroit English speakers to clean up signs there before Expo 2010. The commission had managed to fix more than 10,000 public signs, including “Teliot and urine district”, rewrote English-language historical placards and helped hundreds of restaurants find new ways to word their offerings and fix things like “The tableware reclaims a place” (Translation: drop off dirty dishes here.). ‘signage is to be useful, not to be amusing,” one official said.

Amusing Food and Product Names in China

Because Coca-cola is difficult for Chinese to pronounce and the word "Coca-cola" sounds like "bite the wax tadpole" in Chinese, the company changed the name of the soft drink to ke-kou-ke-le. The slogan "Coke Adds Life" was also changed after Chinese interrupted the slogan as a claim to bring the people back from the dead. The original translation for Kentucky Fried Chicken’s slogan “finger lickin” good” in Chinese was “eat your fingers off.”

Restaurants in China with names like "Accumulated Virtue" and "Unbounded Virtue and Happiness" serve specialties like "Beautiful Butterfly Greeting Guest" (a fish appetizer), "Eight Precious Rice" (a desert made of a sticky rice doused with eight kinds of candied fruit), "Fire Pot Eggs" (a souffle made from thinly slices lily bulbs) and "Dried Fish With Minority Flavor."

Pigeons are regarded as symbols of beauty, and Flying Pigeon bicycles for a long time were one of China's most successful products. Among the other products with amusing names are White Elephant tools, Pansy brand men's underwear, Golden Elephant buses, Flying Man sewing machines, Panda brand cigarettes, Double Swallow rice noodles, 10,000 Precious refrigerators, Person athletic shoes, and Typical sewing machine.

Supermarkets and department stores sell White Cat detergent, White Rabbit creamy candies, Horse Head tissues, Golden Cock alarm clocks, Imperial Concubine tea, Billion Strong Pulpy C orange drink, Moon Rabbit batteries, Long March tires, Gensenocide ginseng products, Flying Baby toilet paper, and Puke cigarettes

Defending Chinglish

Oliver Lutz Radtke, a former German radio reporter who is regarded by some as the world’s foremost authority on Chinglish, told the New York Times he believes that China should embrace the fanciful melding of English and Chinese as the hallmark of a dynamic, living language. As he sees it, Chinglish is an endangered species that deserves preservation. [Source: Andrew Jacobs, New York Times, May 2, 2010]

Oliver Lutz Radtke, a former German radio reporter who is regarded by some as the world’s foremost authority on Chinglish, told the New York Times he believes that China should embrace the fanciful melding of English and Chinese as the hallmark of a dynamic, living language. As he sees it, Chinglish is an endangered species that deserves preservation. [Source: Andrew Jacobs, New York Times, May 2, 2010]

“If you standardize all these signs, you not only take away the little giggle you get while strolling in the park but you lose a window into the Chinese mind,” said Radtke, who is the author of a pair of picture books that feature giggle-worthy Chinglish signs in their natural habitat. Radtke is currently pursuing a doctoral degree in Chinglish at the University of Heidelberg.

Still, the enemies of Chinglish say the laughter it elicits is humiliating. Wang Xiaoming, an English scholar at the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, painfully recalls the guffaws that erupted among her foreign-born colleagues as they flipped through a photographic collection of poorly written signs. They didn’t mean to insult me but I couldn’t help but feel uncomfortable, said Wang, who has since become one of Beijing’s leading Chinglish slayers.

Explaining Chinglish

Those who study the roots of Chinglish say many examples can be traced to laziness and a flawed but wildly popular translation software. Victor H. Mair, a professor of Chinese at the University of Pennsylvania, said the computerized dictionary, Jingshan Ciba, had led to sexually oriented vulgarities identifying dried produce in Chinese supermarkets and the regrettable fried enema menu selection that should have been rendered as fried sausage. [Source: Andrew Jacobs, New York Times, May 2, 2010]

Although improved translation software and a growing zeal for grammatically unassailable English has slowed the output of new Chinglishisms, Mair said he still received about five new examples a day from people who knew he was good at deciphering what went wrong. If someone would pay me to do it, I’d spend my life studying these things, he said.

Among those getting paid to wrestle with Chinglish is Jeffrey Yao, an English translator and teacher at the Graduate Institute of Interpretation and Translation in Shanghai who is leading the sign exorcism. But even as he eradicates the most egregious examples by government fiat — businesses dare not ignore the commission’s suggested fixes — he has mixed feelings, noting that although some Chinglish phrases sound awkward to Western ears, they can be refreshingly lyrical. Some of it tends to be expressive, even elegant, he said, shuffling through an online catalog of signs that were submitted by the volunteers who prowled Shanghai with digital cameras. They provide a window into how we Chinese think about language.

He offered the following example: While park signs in the West exhort people to “Keep Off the Grass,” Chinese versions tend to anthropomorphize nature as a way to gently engage the stomping masses. Hence, such admonishments as “The Little Grass Is Sleeping. Please Don’t Disturb It or Don’t Hurt Me. I Am Afraid of Pain.”

Yao pointed out that this linguistic mentality helped create such expressions as long time no see, a word-for-word translation of a Chinese expression that became a mainstay of spoken English. But Yao, who spent nearly two decades working as a translator in Canada, has his limits. He showed a sign from a park designed to provide visitors with the rules for entry, which include prohibitions on washing, scavenging, clothes drying and public defecation, all of it rendered in unintelligible — and in the case of the last item — rather salty English. The sign ended with this humdinger: “Because if the tourist does not obey the staff to manage or contrary holds, Does, all consequences are proud.”

In Crackdown on Chinglish, Issues Standards for English Signs

In 2017, the Chinese government issued standards for English signs at least in part to crackdown on Chinglish. The Strait Times reported: China has had enough of bad English signs and the jokes that come with them. A new standard for English translations has been issued and it is to take effect by December 1. The standard aims to improve the quality of English translations in 13 public arenas, including transportation, entertainment, medicine and financial services, People's Daily. [Source: Strait Times,, 23 June, 2017]

“The guidelines prioritise correct grammar, the paper said, and warns against using rare words and expressions. The translations should not "contain content that damages the images of China or other countries", while discriminatory and "hurtful" words have been banned. Authorities have provided sample translations for reference, and warned against direct translation, People's Daily reported. "The standard will provide linguistic support for the country's reform and opening policies," said an official announcement.

“The report pointed out that the Park of Ethnic Minorities used to be translated as "Racist Park", which was offensive to many. That is just one of many badly translated public signs, menu items and shop names that have generated hilarity, to the amusement of English speakers. Some examples include a fire extinguisher labelled "hand grenade" and direct translations that alert passers-by of an "Execution in Progress" when they mean "Under Construction".

“Websites, blog posts and memes have been created to mock China's infamous Chinglish signs. But some are sad to see them go. Ray Kwong, senior adviser to the University of Southern California's US-China Institute told the South China Morning Post: "Bad translations on signage, menus and whatnot have been part of China's charm since I first visited 30-something years ago."

Hot in the Early 2000s: Mangled English Words

At the end of 2012, the blog China Smack reported: “This list of “terms” have appeared before in various forms, although the actual usage and “popularity” for many of the “English” terms are highly questionable. The original Chinese words or phrases are — or have been — legitimate notable terms and Chinese internet memes, but the English words are attempts to use English wordplay to capture or communicate some amusing angle about them. It is safe to say these are definitely not the hottest English terms related to China on Twitter, but the list gets attention from Chinese netizens every so often for its overall theme of being self-critical of situations and phenomenon found in present-day China and Chinese society. Below is the list with some explanations of the English wordplay, the original Chinese term the English wordplay is based on, or some context for the term:[Source: China Smack, November 26, 2012]

1) Freedamn: Freedom with Chinese characteristics. 2) Smilence: ‘smiles” but keeps one’s ‘silence”, indicating a sort of awkward, mocking, or even dismissive reaction to something. It may also be used by “knowing” Chinese netizens to suggest they know the truth but will refrain from saying anything further, either out of such things as self-preservation, pity, or even disinterest depending on context. 3) Togayther: The original Chinese is an idiom to suggest that love will always find a way, but the English wordplay specifically refers to an attitude of tolerance for homosexuality. 4) Democrazy: “Wishful thinking” regarding democracy. 5) Shitizen: A self-depreciating name for Chinese citizens invented by Chinese netizens, which chinaSMACK translates as “rabble”.

6) Innernet: China’s Internet, referring to Chinese netizens having restricted or unreliable access to foreign websites, thereby promoting Chinese internet users to stick with domestic online sites and services that the government ultimately has control over. 7) Departyment: The relevant (government) departments. Refers to the ambiguous way the government, authorities, and media often refer to government response and action in issues of interest. 8) Chinsumer: Chinese people who go on wild extravagant shopping sprees when abroad. 9) Emotionormal: Emotional stability, a phrase used by the mainstream media to describe the victims and their family’s reaction to the Wenzhou high-speed train crash in 2011. Netizens were aggravated because this term apparently did not reflect reality and was more motivated by what the government wanted of the people. 10) Sexretary: A female secretary involved in an illicit or inappropriate relationship with her boss. 11) Halfyuan: The 50 Cent Party. 13) Canclensor: Broadly refers to internet censorship and those hired to conduct internet censorship in China. [Note: There is probably a typo — it should be "Cancelsor".] 13) Wall.e: A cute name for China’s “firewall”.

6) Innernet: China’s Internet, referring to Chinese netizens having restricted or unreliable access to foreign websites, thereby promoting Chinese internet users to stick with domestic online sites and services that the government ultimately has control over. 7) Departyment: The relevant (government) departments. Refers to the ambiguous way the government, authorities, and media often refer to government response and action in issues of interest. 8) Chinsumer: Chinese people who go on wild extravagant shopping sprees when abroad. 9) Emotionormal: Emotional stability, a phrase used by the mainstream media to describe the victims and their family’s reaction to the Wenzhou high-speed train crash in 2011. Netizens were aggravated because this term apparently did not reflect reality and was more motivated by what the government wanted of the people. 10) Sexretary: A female secretary involved in an illicit or inappropriate relationship with her boss. 11) Halfyuan: The 50 Cent Party. 13) Canclensor: Broadly refers to internet censorship and those hired to conduct internet censorship in China. [Note: There is probably a typo — it should be "Cancelsor".] 13) Wall.e: A cute name for China’s “firewall”.

14) Circusee: Refers to the phenomenon of bystanders gathering around to look on at a commotion, often without getting involved, or the notion that “the people are watching”. The English term itself is a combination of “encircling” and ‘seeing”, the literal translations of each character in the Chinese term. 15) Vegeteal: Refers to stealing vegetables, an activity in Happy Farm, a once highly popular casual online social network game in Mainland China and Taiwan (with analogues around the world), where the players can steal each other’s farm products. 16) Yakshit: This English word is based on [ya( kè xi-], the Chinese transliteration of the Uyghur term “yaxshi”, which means “good” or “great”. The term was made famous by the Xinjiang musical dance program “Happy Life Yaxshi” (formerly “The Party’s Policy Yaxshi”) in the 2010 CCTV Spring Festival’s Gala. Later, “Yaxshi” was often used by netizens to make satiric judgments against the Party and its propaganda.

15) Animale: Male instincts or innate behavior/mentality. 16) Corpspend: The fee for dredging up and recovering dead bodies from a river. The term was first made famous in 2009 when the fishing boat bosses in the Changjiang (Yangtze) River refused to save drowning students near them until the school leaders came to the scene two hours later and offered to pay the 12,000-per-body recovery fee. 17) Suihide: Refers to the game of hide and seek that Yunnan police claim led to the the death of a prisoner in their custody. 18) Niubility: The ability to be niubi 19) Antizen: The “ant tribe”, a term used to describe the demographic of low-income college graduates who settle for a poverty-level existence in the cities of China. Those who belong to the ant tribe class hope that, in time, they will find the jobs for which they were trained for in college. 20) Gunvernment: Refers to Mao Zedong’s quote, “All political power from the barrel of a gun”, sarcastically used today with regards to the authoritarian regime maintained through military control.

21) Propoorty: Refers to the real estate industry and the systematic poverty of various demographics in China in relation to property rights, transactions, and development. 22) Stuck Market: China’s stock market, its performance, and the position of its investors. 23) Livelihard: A play on “livelihood”, suggesting that life in China is “hard”. 24) Stupig: Stupid + pig. 25) Z-turn: An English transliteration of the Chinese term [zhe- teng], which literally means “to toss about” or “to turn from side to side”, and figuratively refers to doing things that are unnecessary or making a fuss without accomplishing anything, as if taking a zigzag route. 26) Gambller: Part transliteration and part suggestive pun on the Chinese term [gàn bù] “cadre”. 27) Goveruption: Refers to the corruption that plagues China’s government. 28) Harmany: The Chinese terms refers to “river crab”, itself a pun on the Chinese term for “harmony” or “harmoniousness”, a government buzzword reflecting its policy of maintaining and fostering social stability. The pun alludes to internet censorship of news and information believed to jeopardize social “harmony”, resulting in a state of disguised harmony (maintained through censorship). “Harmany” itself is clearly a combination of “harm” + “many”, suggesting that the policy of “harmony” simply “harms” “many” people.

Crazy English in China

"Crazy English," a method of learning English that involves shouting out English words at the top of one's lungs, was very popular in the 2000s. Its founder, Xinjiang-born and Beijing-based Li Yang, is paid $20,000 a year by rich parents to teach their kids. Sometimes 40,000 paying customers show up to see him at stadium appearances.

Li Yang, the founder of Crazy English, has a cult-like following, Students sometimes travel for days to see him in person, wave their textbooks in the air like Red Guards with Little Red Books, and burst into tears during the lessons. Sometimes things get out of control and crowds push and shove to such an extent and there is danger of a stampede or people being crushed to death

The main thrust behind Crazy English is shouting, a method that one Chinese newspaper called “English as a Shouted Language.” Li has said that shouting unleashes one’s “international muscles” and makes it easier not only to learn a language but also to turn one’s life around. One happy student told The New Yorker, “When I didn’t know about Crazy English I was a very shy person. I couldn’t say anything. I was timid. Now I am very confident. I can speak to anyone in public, and I can inspire people to speak together.” In China, there are a tradition of reading aloud to improve pronunciation.

Osnos wrote, "Li combines the physical confidence of shouting English at the top of one’s lungswith stridently nationalistic slogans such as “Conquer English to Make China Stronger!” His classroom megalomania has no shortage of critics. “It’s a kind of old witchcraft,” Wang Shuo, one of China’s best-known novelists, wrote.

Crazy English’s Li Yang

Li was brought up by grandparents while his parents served as propagandist in a bleak town in Xinjiang. He was variously described as introverted and uninspired as a student. He enrolled in the mechanical engineering department of Lanzhou University. It was there, while studying English with a friend in1987 that he decided to prepare for a mandatory English test by reading loudly. Later he recalled that by yelling “I could concentrate, I felt really brave. If I stopped yelling, I stopped learning.”

Li never studied English abroad but his wife is Canadian. In 1989 he began teaching English classes to small groups, He soon moved onto to Guangzhou, where his fathers connections helped to get some television and radio work and he became fairly well know. He quickly tired of that though and founded a company with his sister whose name was a phonetic spelling of “crazy” and started giving lectures. By the late 1990s he was regularly filling 3,000-seat arenas, lecturing at the Forbidden City and leading soldiers in English yelling sessions on the top of the Great Wall.

Evan Osnos wrote in The New Yorker: “Li’s indispensable asset is his voice, a full-throated pitchman’s baritone. He delivers it an accent of his own creation that veers between Texan and Midwestern, stretched by roomy vowels...His yelling occupies a specific register: to my era, it’s not quite the shriek reserved for alerting someone to an oncoming truck, but its more urgent than a summons to he dinner table.”

Li, a bundle of energy who regularly goes 36 hors without sleep, acts like a performer at his Crazy English "seminars." He prances around the stage to rock music and shouts out English phrases and nationalist slogans with 20 special gestures. "I enjoy losing face," he and his audience shouts. "Let the voice of China be heard all over the world."

On a lecture in Guangzhou, Osnos wrote, “Li swooped from hectoring to inspiring; he preened for the camera; he mocked Chinese speakers with fancy college degrees. By the time the lecture ended, he had spoken for four hours, without a break in numbing cold — and the crowd was rapt.”

Evan Osnos wrote on The New Yorker website, “I was struck, as people usually are, by his weirdness, and then surprised to discover that he was accompanied off-stage by an exceedingly normal wife: Kim Lee, a tall brunette from Florida who had met him on a business trip to China. They had three kids, and she once told me, “I’m just a mom who came into a bizarre life by happenstance.” [Source: Evan Osnos, The New Yorker, September 13, 2011]

Criticism and Marketing of Crazy English

The jury is still out whether shouting and other Crazy English methods actually helps someone learn a language let alone turn their life around, The linguist Kingsley Bolton, an expert on English teaching in China, calls Li’s program “huckster nationalism.” Some Chinese are reminded of the Cultural Revolution by Li’s methods.

The Chinese novelist Wang Shou wrote, “It’s a kind of old witchcraft: Summon a big crowd of people, get them excited with words, and create a sense of power strong enough to move mountains and overturn the seas...I believe that Li Yang loves the country. But act this way and your patriotism, I fear, will become the same shit as racism.”

Li gives about 300 lectures a year. About 30 million people have taken his courses as of 2005. The key to his success is perhaps his mix of nationalism and inspiration lectures. Among the things he tells his audience are: “English is merely a tool for earning money. It’s an inferior language that relies on an alphabet with just 26 letters. How can it even compare to our language with a sea of Chinese characters.”

Another secret of the success of Crazy English has been the ability of Li and his marketing staff to lure people in and keeping them dishing out money for lessons, lectures, books and other products. Li’s name is found on more than 100 books, videos, DVDs, audio boxed sets and software packages with names like “Li Yang Crazy English Blurt Out MP3 Collection.”

Some Crazy English schools are called Tongue Muscle Training Houses. The Crazy Intensive Winter Training Camp has military feel, with instructors dressed in camouflage, using megaphones to communicate. Students sleep in freezing cold, unheated dormitories, run at dawn shouting English and end their stay by walking on hot coals. Speaking English is tied with physical strength and physical strength, Crazy English instructors say, is tied to national powers.

Crazy English has a strong nationalist bent as manifested by some of the slogans that students shout out such as “Conquer English to Make China Stronger!” In his books Li described the United States, Japan and the countries of Europe as nations that have gone astray and “don’t want China to be big and powerful!” “What they want most is for China’s youth to have long hair, wear bizarre clothes, drink soda...have no fighting spirit, love pleasure and comfort!, Li said. “The more China’s youth degenerates the happier they are.” When asked why it is necessary for Chinese to lean English he said, “Because were pity foreigners for not being able to speak Chinese.”

Li said that before he devised the shouting, crazy method of learning English he was shy "tofu scum" and failed his college English class. "You can concentrate your mind better when you shout" he said. He credits the method with improving his English and overcoming his shyness.

Crazy English Teacher Accused of Domestic Violence

Evan Osnos wrote on The New Yorker website, In September 2011, Li's American wife Kim Lee "publicly posted photos of her herself online with severe bruises on her head and knees and, in a series of Twitter-like messages, she vowed to seek a divorce. (She wrote, “You knocked me to the floor. You sat on my back. You choked my neck with both hands and slammed my head into the floor. When I pried your hands from my neck you grabbed my hair and slammed my head into the floor ten more times!”)

"In China, it was a sensation, drawing headlines and thousands of online comments; people condemned the Crazy English founder and demanded that he respond. For days Li stayed silent, but later he admitted to “domestic violence” against his wife and kids that “caused them serious physical and mental damage.” In a strange interview with China Daily...he sounded less than contrite, saying the “problem involves character and cultural differences, which are difficult to solve through counseling.” According to the article, he also said, “I hit her sometimes but I never thought she would make it public since it’s not Chinese tradition to expose family conflicts to outsiders. But I still respect her for raising three girls on her own and for her passion for her students.”

"If there is anything positive to be sifted from the sad affair, it is that the case has focused attention to China’s under-discussed problems of domestic violence, especially in high-income urban families. When it is discussed, abuse is usually described as a problem left over in remote rural areas, but Li’s case has prompted Chinese counselors to report that “nearly half of domestic violence abusers are people who have higher education, senior jobs and social status.”"

NPR reported: “ Their 18-month legal battle became the country's most closely watched divorce case. When the verdict finally came on February 3, 2013, it made the nightly news. A Beijing court ruled in Kim Lee's favor, granting her a divorce, custody of their three children, compensation of $8,000 for the abuse and assets of almost $2 million. The court issued a restraining order against her ex-husband — the first time ever in Beijing. [Source: NPR, February 7, 2013]

Image Sources: Mostly from Asia Obscura . Also Crazy English, Pardo com; 3) Chinglish poco pico blog and Wikipedia

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated September 2021