REPUBLICAN CHINA

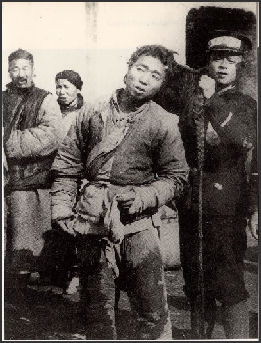

Cutting of the queue in 1911

The 1911 Revolution — also known as the Xinhai Revolution — culminated in 1912 finally overthrew Qing (Manchu) imperial rule over China. The new Chinese republic soon fell apart and passed into the hands of warlords. China had a peripheral role in World War I (1913–18) on the Allied side in 1917. After the war, the Kuomintang (Chinese nationalist party) formed an alliance with the communists built a strong, disciplined political force. The leader of the Kuomintang — Chiang Kai-shek (Jiang Jieshi) — unified China under Nationalist rule in 1928, establishing a capital in Nanjing and then undertook a bloody purge of the communists to gain full control of the government. The communists sought refuge in the mountains of southern Jiangxi Province and from there undertook the Long March during 1934–35 under the leadership of Mao Zedong, who set up a stronghold in Yan’an (Yenan). [Source: Junior Worldmark Encyclopedia of the Nations, Thomson Gale, 2007]

According to “Countries of the World and Their Leaders”: “Frustrated by the Qing court's resistance to reform, young officials, military officers, and students—inspired by the revolutionary ideas of Sun Yat-sen — began to advocate the over-throw of the Qing dynasty and creation of a republic. A revolutionary military uprising on October 10, 1911, led to the abdication of the last Qing monarch. As part of a compromise to overthrow the dynasty without a civil war, the revolutionaries and reformers allowed high Qing officials to retain prominent positions in the new republic. [Source: “Countries of the World and Their Leaders Yearbook,” 2009, Gale, 2008]

One of these figures, Gen. Yuan Shikai, was chosen as the republic's first president. Before his death in 1916, Yuan unsuccessfully attempted to name himself emperor. His death left the republican government all but shattered, ushering in the era of the “warlords” during which China was ruled and ravaged by shifting coalitions of competing provincial military leaders.In the 1920s, Sun Yat-sen established a revolutionary base in south China and set out to unite the fragmented nation. With Soviet assistance, he organized the Kuomintang (KMT or “Chinese Nationalist People's Party”), and entered into an alliance with the fledgling Chinese Communist Party (CCP). After Sun's death in 1925, one of his proteges, Chiang Kai-shek, seized control of the KMT and succeeded in bringing most of south and central China under its rule.

Early 20th Century China : John Fairbank Memorial Chinese History Virtual Library cnd.org/fairbank offers links to sites related to modern Chinese history (Qing, Republic, PRC) and has good pictures; Website on the Qing Dynasty Wikipedia Wikipedia ; Qing Dynasty Explained drben.net/ChinaReport ; Recording of Grandeur of Qing learn.columbia.edu Empress Dowager Cixi: Court Life During the Time of Empress Dowager Cixi etext.virginia.edu; Wikipedia article Wikipedia Books on Cixi royalty.nu; The Last Emperor Puyi Wikipedia article Wikipedia ; His Widow's Account hartford-hwp.com/archives; Puyi Biography royalty.nu/Asia;

RELATED ARTICLES IN THIS WEBSITE: REPUBLICAN CHINA, MAO AND THE EARLY COMMUNIST PERIOD factsanddetails.com; REFORMERS, MODERNIZATION AND REFORM EFFORTS IN CHINA IN THE LATE 1800s factsanddetails.com; OBSERVATIONS BY CHINESE ON LIFE IN THE WEST factsanddetails.com; MAY 4TH MOVEMENT AND THE POLITICAL IDEAS AND REFORMERS ITS SPAWNED factsanddetails.com; KUOMINTANG AND CHINESE WARLORDS factsanddetails.com; SUN YAT-SEN AND REPUBLICAN CHINA factsanddetails.com; CHIANG KAI-SHEK AND MADAME CHIANG KAI-SHEK factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: “The Birth of a Republic” by Hanchao Lu Amazon.com; “Republican China: Nationalism, War, and the Rise of Communism 1911-1949" by Franz Schurmann and Orville Schell Amazon.com; The Cambridge History of China, Vol. 12: Republican China, 1912-1949, Part 1 by John K. Fairbank Amazon.com; The Cambridge History of China, Vol. 13: Republican China 1912-1949, Part 2 by John K. Fairbank and Albert Feuerwerker Amazon.com; “Empress Dowager Cixi: The Concubine Who Launched Modern China” by Jung Chang Amazon.com; “Sun Yat-sen” by Marie-Claire Bergère and Janet Lloyd Amazon.com; “The Unfinished Revolution: Sun Yat-Sen and the Struggle for Modern China” by Tjio Kayloe Amazon.com; “The Chinese Enlightenment: Intellectuals and the Legacy of the May Fourth Movement of 1919" by Vera Schwarcz Amazon.com; "The Generalissimo: Chiang Kai-Shek and the Struggle for Modern China" by Jay Taylor Amazon.com; “Penguin History of Modern China: 1850-2009” by Jonathan Fenby Amazon.com;; "China: A New History" by John K. Fairbank Amazon.com

Upheaval and Chaos in China During the Early Republican Period

Beheaded revolutionists in Wuchang

The end of imperial rule was followed by nearly four decades of major socioeconomic development and sociopolitical discord. The initial establishment of a Western-style government — the Republic of China — was followed by several efforts to restore the throne. Lack of a strong central authority led to regional fragmentation, warlordism, and civil war. The main figure in the revolutionary movement that overthrew imperial rule was Sun Yat-sen (1866-1925), who, along with other republican political leaders, endeavored to establish a parliamentary democracy. They were thwarted by warlords with imperial and quasi-democratic pretensions who resorted to assassination, rebellion, civil war, and collusion with foreign powers (especially Japan) in their efforts to gain control.

Ignored by the Western powers and in charge of a southern military government with its capital in Guangzhou, Sun Yatsen eventually turned to the new Soviet Union for inspiration and assistance. The Soviets obliged Sun and his Kuomintang (Guomindang, Nationalist Party). Soviet advisers helped the Kuomintang establish political and military training activities. But Moscow also supported the new Chinese Communist Party (CCP), which was founded by Mao Zedong (1893-1976) and others in Shanghai in 1921. The Soviets hoped for consolidation of the Kuomintang and the CCP but were prepared for either side to emerge victorious. The struggle for power in China began between the Kuomintang and the CCP as both parties also sought the unification of China.

A major political and social movement during this time was the May Fourth Movement (1919), in which calls for the study of “science” and “democracy” were combined with a new patriotism that became the focus of an anti-Japanese and antigovernment movement. Sun’s untimely death from illness in 1925 brought a split in the Kuomintang and eventually an uneasy united front between the Kuomintang and the CCP.

Political and Social Conditions at the Time of the Chinese Republic

Wolfram Eberhard wrote in “A History of China”: “The situation of the Republic after its foundation was far from hopeful. Republican feeling existed only among the very small groups of students who had modern education, and a few traders, in other words, among the "middle class". And even in the revolutionary party to which these groups belonged there were the most various conceptions of the form of republican state to be aimed at. The left wing of the party, mainly intellectuals and manual workers, had in view more or less vague socialistic institutions; the liberals, for instance the traders, thought of a liberal democracy, more or less on the American pattern; and the nationalists merely wanted the removal of the alien Manchu rule. The three groups had come together for the practical reason that only so could they get rid of the dynasty. They gave unreserved allegiance to Sun Yat-sen as their leader. He succeeded in mobilizing the enthusiasm of continually widening circles for action, not only by the integrity of his aims but also because he was able to present the new socialistic ideology in an alluring form. The anti-republican gentry, however, whose power was not yet entirely broken, took a stand against the party. The generals who had gone over to the republicans had not the slightest intention of founding a republic, but only wanted to get rid of the rule of the Manchus and to step into their place. This was true also of Yuan Shikai, who in his heart was entirely on the side of the gentry, although the European press especially had always energetically defended him. In character and capacity he stood far above the other generals, but he was no republican. [Source: “A History of China” by Wolfram Eberhard, 1951, University of California, Berkeley]

Dog devouring the remains of killed soldiers

“Thus the first period of the Republic, until 1927, was marked by incessant attempts by individual generals to make themselves independent. The Government could not depend on its soldiers, and so was impotent. The first risings of military units began at the outset of 1912. The governors and generals who wanted to make themselves independent sabotaged every decree of the central government; especially they sent it no money from the provinces and also refused to give their assent to foreign loans. The province of Canton, the actual birthplace of the republican movement and the focus of radicalism, declared itself in 1912 an independent republic.

“Within the Beijing government matters soon came to a climax. Yuan Shikai and his supporters represented the conservative view, with the unexpressed but obvious aim of setting up a new imperial house and continuing the old gentry system. Most of the members of the parliament came, however, from the middle class and were opposed to any reaction of this sort. One of their leaders was murdered, and the blame was thrown upon Yuan Shikai; there then came, in the middle of 1912, a new revolution, in which the radicals made themselves independent and tried to gain control of South China. But Yuan Shikai commanded better troops and won the day. At the end of October 1912 he was elected, against the opposition, as president of China, and the new state was recognized by foreign countries.

Border States at the Time of the Chinese Republic

Wolfram Eberhard wrote in “A History of China”: “China's internal difficulties reacted on the border states, in which the European powers were keenly interested. The powers considered that the time had come to begin the definitive partition of China. Thus there were long negotiations and also hostilities between China and Tibet, which was supported by Great Britain. The British demanded the complete separation of Tibet from China, but the Chinese rejected this (1912); the rejection was supported by a boycott of British goods. In the end the Tibet question was left undecided. Tibet remained until recent years a Chinese dependency with a good deal of internal freedom. The Second World War and the Chinese retreat into the interior brought many Chinese settlers into Eastern Tibet which was then separated from Tibet proper and made a Chinese province (Hsi-Kang) in which the native Khamba will soon be a minority. The communist regime soon after its establishment conquered Tibet (1950) and has tried to change the character of its society and its system of government which lead to the unsuccessful attempt of the Tibetans to throw off Chinese rule (1959) and the flight of the Dalai Lama to India. The construction of highways, air and missile bases and military occupation have thus tied Tibet closer to China than ever since early Manchu times. [Source: “A History of China” by Wolfram Eberhard, 1951, University of California, Berkeley]

“In Outer Mongolia Russian interests predominated. In 1911 there were diplomatic incidents in connection with the Mongolian question. At the end of 1911 the Hutuktu of Urga declared himself independent, and the Chinese were expelled from the country. A secret treaty was concluded in 1912 with Russia, under which Russia recognized the independence of Outer Mongolia, but was accorded an important part as adviser and helper in the development of the country. In 1913 a Russo-Chinese treaty was concluded, under which the autonomy of Outer Mongolia was recognized, but Mongolia became a part of the Chinese realm. After the Russian revolution had begun, revolution was carried also into Mongolia. The country suffered all the horrors of the struggles between White Russians (General Ungern-Sternberg) and the Reds; there were also Chinese attempts at intervention, though without success, until in the end Mongolia became a Soviet Republic. As such she is closely associated with Soviet Russia. China, however, did not quickly recognize Mongolia's independence, and in his work China's Destiny (1944) Chiang Kai-shek insisted that China's aim remained the recovery of the frontiers of 1840, which means among other things the recovery of Outer Mongolia. In spite of this, after the Second World War Chiang Kai-shek had to renounce de jure all rights in Outer Mongolia. Inner Mongolia was always united to China much more closely; only for a time during the war with Japan did the Japanese maintain there a puppet government. The disappearance of this government went almost unnoticed.

“At the time when Russian penetration into Mongolia began, Japan had entered upon a similar course in Manchuria, which she regarded as her "sphere of influence". On the outbreak of the first world war Japan occupied the former German-leased territory of Tsingtao, at the extremity of the province of Shandong, and from that point she occupied the railways of the province. Her plan was to make the whole province a protectorate; Shandong is rich in coal and especially in metals. Japan's plans were revealed in the notorious "Twenty-one Demands" (1915). Against the furious opposition especially of the students of Beijing, Yuan Shikai's government accepted the greater part of these demands. In negotiations with Great Britain, in which Japan took advantage of the British commitments in Europe, Japan had to be conceded the predominant position in the Far East.

Xinhai Revolution: the Republican Revolution of 1911 That Ended the Qing Dynasty

The Qing Dynasty was brought down by a highly organized revolutionary movement with overseas arms and financing and a coherent governing ideology based on republican nationalism. Failure of reform from the top and the fiasco of the Boxer Uprising convinced many Chinese that the only real solution lay in outright revolution, in sweeping away the old order and erecting a new one patterned preferably after the example of Japan. The conflict that brought down the Qing today is called the Republican Revolution of 1911 or the Xinhai Revolution.

Sun Yat-sen was then a republican and anti-Qing activist who became increasingly popular among the overseas Chinese and Chinese students abroad, especially in Japan. In 1905 Sun founded the Tongmeng Hui (United League) in Tokyo with Huang Xing (1874-1916), a popular leader of the Chinese revolutionary movement in Japan, as his deputy. This movement, generously supported by overseas Chinese funds, also gained political support with regional military officers and some of the reformers who had fled China after the Hundred Days' Reform. [Source: The Library of Congress]

“A revolution that finally overthrew Manchu rule began in 1911 in the context of a protest against a government scheme that would have handed Chinese-owned railways to foreign interests. It broke out on October 10, 1911, in Wuchang, the capital of Hubei Province, among discontented modernized army units whose anti-Qing plot had been uncovered. It had been preceded by numerous abortive uprisings and organized protests inside China. The revolt quickly spread to neighboring cities.A month later, Sun Yat-sen returned to China from the United States, where he had been raising funds among overseas Chinese and American sympathizers.

On January 1, 1912, Sun was inaugurated in Nanjing as the provisional president of the new Chinese republic. But power in Beijing already had passed to the commander-in-chief of the imperial army, Yuan Shikai, the strongest regional military leader at the time. To prevent civil war and possible foreign intervention from undermining the infant republic, Sun agreed to Yuan's demand that China be united under a Beijing government headed by Yuan. On February 12, 1912, the 6-year-old child emperor of the Qing Dynasty abdicated, ending more than 2,000 years of imperial rule in China. On March 10, in Beijing, Yuan Shikai was sworn in as provisional president of the Republic of China.

March of the revolutionary army on Wuhan

Background Behind the Xinhai Revolution

Pamela Kyle wrote in the Wall Street Journal, “China has a long history of uprisings against corrupt officials, high rents and foreign trespass. From the end of the 19th century, the Chinese demonstrated and occasionally rebelled against territorial seizures by foreign powers, the intrusion of foreign goods into Chinese markets, the foreign monopoly on railroads, official corruption and military incompetence. This resistance became a resource for those attempting to concentrate the fire of public discontent on the Qing court. [Source: Pamela Kyle, Wall Street Journal, October 9, 2011]

Traditional Chinese society was skilled in organizing the resources necessary for sustaining civil action — and uncivil if needed — against the government. The power of the Chinese public to mobilize fuels reform and creativity in China, while marking some real limits to government abuse. This continues to define the Chinese identity in the 21st century. Yet it is so loathed by the Chinese Communist Party that even the phrase "civil society" is banned online and in print.

The 1911 revolution was also international in origin and orientation. Its leading figures, including Sun Yat-sen, had been raised at the margins of traditional China, or had spent their entire adult lives abroad — whether in the British colony of Hong Kong, the United States and its Pacific possessions, the European colonies of Southeast Asia, or the cities and universities of liberal Meiji Japan. They were accustomed to legal protections on political speech, the idea of impartial government and the prospect of democracy.

After being banished from the Qing territories in the 1890s, reformers and revolutionaries traveled to or published in the Chinese communities of the Pacific, Latin America, North America and Europe to raise money for their cause. Not surprisingly, when the new republic was erected, its international orientation persisted, though it lost some credibility as Japan became financially and militarily more predatory. Nevertheless, collaborative relations with the United States, the Soviet Union and Europe (including the despatch of more than 100,000 men to support British and French armies in World War I) remained a defining element of the first Chinese Republic, and in many forms persisted in the P.R.C. until the late 1950s.

China was part of the Qing empire, ruled by foreign invaders, the Manchus. The Chinese themselves had no armies, no defined boundaries and above all no concept of national sovereignty. At the end of the 19th century, as in the cases of many peoples entering the twilight of the great land empires, Chinese leaders arose who claimed the banner of nationalism. Their opposition to the Qing, British and French empires was clear enough. What was unclear was the basis of this nationalism once the Qing fell and the assaults of foreign empires withered away.

Battle neat Hankow

Wuchang Uprising

Robert Saiget of AFP wrote: “When the army of the Qing Dynasty turned its guns on the state on October 10, 1911, it signalled the end of 2,000 years of imperial rule in China and the promise of a democratic republican government.The first shots were fired in Wuchang part of today's city of Wuhan sparking battles between imperial forces and rebel soldiers during which 16 other regions declared independence in what has come to be known as the Xinhai Revolution. The Wuchang Uprising led to the establishment of the Republic of China by revolutionary Sun Yat-sen's Nationalist Party, which fought under the banner of nationalism, democracy and the people's livelihood. [Source: Robert Saiget, AFP, October 10, 2011]

The revolt quickly spread to neighboring cities, and Tongmeng Hui members throughout the country rose in immediate support of the Wuchang revolutionary forces. By late November, fifteen of the twenty-four provinces had declared their independence of the Qing empire. "The eruption of the Xinhai Revolution overthrew several thousand years of imperial rule and has had a huge impact on the psychology of the Chinese people," historian Lei Yi of the China Academy of Social Sciences told AFP. "The Communist Party believes that they are continuing the spirit of the Xinhai Revolution and that the Nationalists betrayed the revolution."

China marked the centennial of the Wuchang Uprising with the release of "1911", a big-budget historical movie directed by Jackie Chan, and a new museum in the central metropolis of Wuhan where it began. But the celebrations were muted, particularly compared with those that marked the 90th birthday in July of the ruling Communist Party. That, say experts, is because of the troublesome connotations with democracy and Taiwan. October 10, the day the Wuchang Uprising began, is celebrated as Taiwan's national day.

"Wuhan has always been proud of the Wuchang Uprising and its contribution to China's development, but the people are actually very indifferent to it," said retiree Guo Xinglian as he strolled in a park near where the uprising began. "Today a lot of people think the Communist Party is more corrupt than the Qing Dynasty, but they also know that the Communist Party is very strong and any attempt at an uprising will be crushed."

Rebels entrenched at Kilometer 10

After the 1911 Revolution

According to the “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Nations”: The Chinese republic, ruled briefly by Sun Zhongshan (Sun Yatsen), followed by Yuan Shikai (Yuän Shihkai), entered upon a period of internal strife. Following Yuan's death in 1916, the Beijing regime passed into the hands of warlords. The Beijing regime joined World War I on the Allied side in 1917. In 1919, the Versailles Peace Conference gave Germany's possessions in Shandong to Japan, sparking the May Fourth Movement as student protests grew into nationwide demonstrations supported by merchants and workers. This marked a new politicization of many social groups, especially those intellectuals who had been emphasizing iconoclastic cultural change.

“Belated domestic reforms failed to stem a revolution long-plotted, chiefly by Sun Yat-sen, and set off in 1911 after the explosion of a bomb at Wuchang. With relatively few casualties, the Qing dynasty was overthrown and a republic was established. Sun, the first president, resigned early in 1912 in favor of Yuan Shih-kai, who commanded the military power. Yuan established a repressive rule, which led Sun's followers to revolt sporadically. [Source: “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Nations”, Thomson Gale, 2007]

Sebastian Veg wrote in the The China Beat, “China’s 1911 Revolution ushered in a constitutional monarchy, rapidly followed by the proverbial “first Republic in Asia, “with Sun Yat-sen as its short-lived first president. The 1911 revolution, whether because of the initial weakness of its proponents or through a series of unlucky historical coincidences, rapidly led to the restoration of Yuan Shikai to the imperial throne. The long-anticipated democratic system and the greater social and civic equality that was to result from it remained elusive, prompting a decade of soul-searching among China’s intellectuals. The most famous product of these reflections was without doubt Lu Xun’s Ah Q, the epitome of a revolutionary who is unequipped and unable to become a citizen. How were China’s Ah Qs to be made into citizens” This became the foremost preoccupation of the country’s intellectual elite for many years, setting them apart from the world of power politics. The New Culture movement, with its emphasis on education and individual autonomy, was followed by cultural agendas that became increasingly utopian as politics became more cynical and polarized. When Duan Qirui sent his troops into Beijing, Lu Xun’s brother Zhou Zuoren took his Beijing University students to study in the countryside, emulating the Japanese “New Village movement.” As Chiang Kai-shek massacred supposed communist sympathizers, Liang Shuming set up utopian rural schools in China’s remote backwaters. “Real” democracy was always seen as outside the corrupt institutions of party politics; however, the utopian vision of “fostering citizens” never led to the desired changes in the political system. Similarly to Weimar Germany, the Republic of China was a time of great freedom and intellectual ferment, but also a Republic without republicans, a regime whose institutions no one was prepared to invest in.

1911 Revolution and Efforts to Reform China

Sebastian Veg wrote in the The China Beat, “ Although political change had been expected, the revolution itself came as something of a surprise at the end of a decade of political reforms known as the “New policy “by the Manchu court, which had already largely transformed the organization of the Chinese state. The abolition of the century-old system of civil service examinations, the election of various provincial-level assemblies (albeit by a very small franchise) which fostered the power of the local gentry, the establishment of modern schools and universities, and the influx of western commodities and techniques under the motto “Chinese learning as substance, Western learning as function” all took place during the last years of Qing rule. When the revolution finally occurred, it came as the icing on the cake of an incremental institution-building process that had taken place over the preceding decade. [Source: Sebastian Veg, The China Beat, October 10, 2011. Sebastian Veg is the director of the French Centre for Research on Contemporary China (Hong Kong). He has published a monography on Lu Xun and European modernism, and his current research interests are in the area of literature and intellectuals in modern and contemporary China.]

Pitched battle between imperial and revolutionary army

However, the top-down reforms launched by the court throughout the 1900s were at the same time being outpaced by the growing radicalization of China’s intellectuals, many of whom spent this decade in Japan. While Kang Youwei’s idea of a constitutional, Confucian monarchy had appeared as revolutionary in 1898, by 1911 Kang was seen by most progressive thinkers and activists as a hopeless and eccentric reactionary. Even Liang Qichao, one of the most prominent and widely-read advocates of constitutionalism and an admirer of the British system, was outflanked by the cultural and political vanguard represented by activists like Zhang Binglin (Zhang Taiyan), the editor of the influential Minbao, published in Tokyo. Zhang and many of his followers, in particular the group known as the “Tokyo anarchists”, criticized what they saw as the pro-Western bias in the institution-building process and advocated a different kind of democracy, rooted in social equality and inspired by archaic and often esoteric Chinese thinkers.

"In this manner, mistrust of institutions remained strong among critical Chinese intellectuals for most of the century, and was notably instrumentalized to great effect by Mao during the Cultural Revolution — which is not to say that “organic” intellectuals did not crave recognition from the state when the opportunity arose. However, it was only after the beginning of Reform and Opening up that the Chinese elite again warmed to the theme of institution building: throughout the 1980s — a decade of intellectual ferment and political reform in many ways similar to the 1900s — the feeling dominated that an institutional compromise was possible between inner-Party reformers and idealistic intellectuals. After the violent crackdown of the 1989 student movement, a similar pattern emerged: rather than embarking on an uncertain long march through the institutions, many of China’s foremost critical thinkers once again took refuge in other realms: academia, legal activism, grassroots civil society organizations, personal investigations of recent history, documentary films, or emigration. Only Liu Xiaobo, loyal to the spirit of the 1980s, reaffirmed his commitment to formulating an institutional alternative, demonstrated most clearly in the Charter 08 he co-authored. On the whole, however, institutional reform was seen as both hopeless and useless (a point tragically demonstrated by Liu’s arrest) and the real battles were elsewhere.

"It took almost one century from the fall of the Bastille until French citizens of all political stripes could to come together at the funeral of Republican icon Victor Hugo, a sign, according to historian François Furet’s famous pronouncement, that “Revolution had entered port.” This has not happened in China. To the contrary, the opening ceremony of the Beijing Olympics in 2008, with its carefully crafted historical narrative, took great pains to avoid sketching out a possible political consensus on how to define the nation in the 20th century, closely confining itself to the cultural bric-a-brac of its “5,000-year history.” This absence of even a minimal consensus on the nature of the Chinese polity speaks eloquently to the open legacy of 1911. One hundred years on, the divide between an institutional apparatus that seems less and less amenable to reform and an aspirational form of democracy that has not yet found a satisfactory institutional translation on the Chinese mainland remains as deep as ever.

Captured Republican prisoners

Elections in China in 1912 and 1913

In August 1912 a new political party was founded by Song Jiaoren (1882-1913), one of Sun Yat-sen's associates. The party, the Kuomintang (Guomindang or KMT — the National People's Party, frequently referred to as the Nationalist Party), was an amalgamation of small political groups, including Sun's Tongmeng Hui. In the national elections held in February 1913 for the new bicameral parliament, Song campaigned against the Yuan administration, and his party won a majority of seats.The Economist reported: “In the elections of December 1912 to early 1913 more than 10 percent of the Chinese population would be eligible to cast votes, an elite but still large group of 40 million male taxpayers who owned some property and had a primary-school education. (Women had not won the right to vote; one suffragist slapped Song in the face for not taking up their cause.) China’s first real democratic campaign had begun. What did this first go at democracy look like? Partisans roughed up opposing candidates and activists, carried guns near polling stations to intimidate voters, bought votes with cash, meals and prostitutes (some lamented selling too early, as prices went up closer to election day), and stuffed ballot boxes. At least one victorious candidate was falsely accused of being an opium-taker. In a word, it looked like democracy. Some historians discount these reports as scattered abuses in a fairly clean election. The Nationalists were accused of the preponderance of the election shenanigans, and they won in a rout, in effect taking half the seats in the legislature. [Source: The Economist, December 22, 2012]

While the Republic prepared for its first elections President Yuan Shikai ran roughshod over the new government. He was also canny, ruthless and megalomaniacal. Yuan did not want a strong prime minister, nor did he want the Nationalist Party to write a constitution that would limit his own power. He most certainly did not want democracy—and snuffed it out. In 1915 he tried to restore imperial rule and have himself made emperor. His death in 1916 left a divided country, fought over by warlords and bandits.

“Jonathan Spence, a historian, writes that Liang Qichao—the pre-eminent Chinese intellectual of the era, an erstwhile monarchist and at that moment a close ally of Yuan’s— had come back to China to help organise a pro-Yuan party. He took this defeat for the authoritarians terribly, writing to his daughter, “What can one do with a society like this one? I’m really sorry I ever returned.” Disgusted, and believing his opponents had cheated, Liang would temporarily throw in his lot with Yuan’s rule, even as evidence suggested the president had assassinated his chief political rival. Ever the operator, Yuan worked to reverse the Nationalist victory at the polls by buying off elected officials, later banning the party altogether.

After the Election in 1913

The Kuomintang of China was one of the dominant parties of the early Republic of China, from 1912 onwards, and remains one of the main political parties in modern Taiwan. The Kuomintang won an overwhelming majority of the first National Assembly in December 1912. But Yuan soon began to ignore the parliament in making presidential decisions and had parliamentary leader Song Jiaoren assassinated in Shanghai in 1913. Members of the KMT led by Sun Yat-sen staged the Second Revolution in July 1913, a poorly planned and ill-supported armed rising to overthrow Yuan, and failed. Yuan, claiming subversiveness and betrayal, expelled adherents of the Kuomintang from the parliament. Yuan dissolved the KMT in November (whose members had largely fled into exile in Japan) and dismissed the parliament early in 1914. [Source: Wikipedia]

Amidst the anarchy that followed the collapse of Qing Dynasty, Sun made the bold decision of transforming his revolutionary society into a mainstream political party. The result: the Kuomintang (KMT or Nationalist Party), which emerged as the dominant political party in China. The Kuomintang won in China's first ever national elections in 1913 but didn’t hold on to power for long. The republic that Sun Yat-sen and his associates envisioned evolved slowly. The revolutionists lacked an army, and the power of Yuan Shikai began to outstrip that of parliament. Yuan revised the constitution at will and became dictatorial.

Yuan Shikai

Sun's power and charisma unfortunately was not enough to overcome the military muscle of China's divided warlords and the remnants of the Manchu army and forge China into a true nation. With the preservation of the republic taking precedence over his own ambitions, Sun relinquished power after only three months to Gen. Yuan Shikai, a commander in the Manchu Army who promised to get the Manchu's to surrender and install a republican government. Yuan Shikai had helped Sun's Nationalists to force the Manchu abdication. But once the KMT was in power Yuan reneged on his promise and set about shoring up his power by murdering political opponents, ignoring the new constitution, ruthlessly putting down local uprisings and later named himself emperor of a new dynasty.

While exiled in Japan in 1914, Sun established the Chinese Revolutionary Party, but many of his old revolutionary comrades, including Huang Xing, Wang Jingwei, Hu Hanmin and Chen Jiongming, refused to join him or support his efforts in inciting armed uprising against Yuan Shikai. In order to join the Chinese Revolutionary Party, members must take an oath of personal loyalty to Sun, which many old revolutionaries regarded as undemocratic and contrary to the spirit of the revolution. [Source: Wikipedia Thus, many old revolutionaries did not join Sun's new organisation, and he was largely sidelined within the Republican movement during this period. Sun returned to China in 1917 to establish a rival government at Guangzhou, but was soon forced out of office and exiled to Shanghai. There, with renewed support, he resurrected the KMT on October 10, 1919, but under the name of the Chinese Kuomintang, as the old party had simply been called the Kuomintang. In 1920, Sun and the KMT were restored in Guangdong.

Yuan Shikai Becomes the Leader of China

After Yuan had Song assassinated in March 1913, animosity towards him grew. In the summer of 1913 seven southern provinces rebelled against Yuan. When the rebellion was suppressed, Sun and other instigators fled to Japan. In October 1913 an intimidated parliament formally elected Yuan president of the Republic of China, and the major powers extended recognition to his government. To achieve international recognition, Yuan Shikai had to agree to autonomy for Outer Mongolia and Tibet. China was still to be suzerain, but it would have to allow Russia a free hand in Outer Mongolia and Britain continuance of its influence in Tibet. [Source: The Library of Congress]

In November 1913, Yuan Shikai, legally president, ordered the Kuomintang dissolved and its members removed from parliament. Within a few months, he suspended parliament and the provincial assemblies and forced the promulgation of a new constitution, which, in effect, made him president for life. Yuan's ambitions still were not satisfied, and, by the end of 1915, it was announced that he would reestablish the monarchy. Widespread rebellions ensued, and numerous provinces declared independence. With opposition at every quarter and the nation breaking up into warlord factions.

Wolfram Eberhard wrote in “A History of China”: “Meanwhile Yuan Shikai had made all preparations for turning the Republic once more into an empire, in which he would be emperor; the empire was to be based once more on the gentry group. In 1914 he secured an amendment of the Constitution under which the governing power was to be entirely in the hands of the president; at the end of 1914 he secured his appointment as president for life, and at the end of 1915 he induced the parliament to resolve that he should become emperor. [Source: “A History of China” by Wolfram Eberhard, 1951, University of California, Berkeley]

“This naturally aroused the resentment of the republicans, but it also annoyed the generals belonging to the gentry, who had the same ambition. Thus there were disturbances, especially in the south, where Sun Yat-sen with his followers agitated for a democratic republic. The foreign powers recognized that a divided China would be much easier to penetrate and annex than a united China, and accordingly opposed Yuan Shikai. Before he could ascend the throne, he died suddenly of natural causes in June 1916, deserted by his lieutenants—and this terminated the first attempt to re-establish monarchy.

After Yuan Shikai China Deteriorates Into Warlordism

Chinese warlord Feng Yuxiang

After Yuan Shikai's death in 1916, China deteriorated into anarchy as fragmented states ruled by rival warlords fought for control. The predecessors of the Communist party that existed at this time consisted of discussion groups at Beijing University who argued over points in the Communist Manifesto.

Wolfram Eberhard wrote in “A History of China”: “Yuan was succeeded as president by Li Yuanhong. Meanwhile five provinces had declared themselves independent. Foreign pressure on China steadily grew. She was forced to declare war on Germany, and though this made no practical difference to the war, it enabled the European powers to penetrate further into China. Difficulties grew to such an extent in 1917 that a dictatorship was set up and soon after came an interlude, the recall of the Manchus and the reinstatement of the deposed emperor (July 1st-8th, 1917). [Source: “A History of China” by Wolfram Eberhard, 1951, University of California, Berkeley]

“This led to various risings of generals, each aiming simply at the satisfaction of his thirst for personal power. Ultimately the victorious group of generals, headed by Tuan Ch'i-jui, secured the election of Fêng Kuo-chang in place of the retiring president. Fêng was succeeded at the end of 1918 by Hsu Shih-ch'ang, who held office until 1922. Hsu, as a former ward of the emperor, was a typical representative of the gentry, and was opposed to all republican reforms.

“The south held aloof from these northern governments. In Canton an opposition government was set up, formed mainly of followers of Sun Yat-sen; the Beijing government was unable to remove the Canton government. But the Beijing government and its president scarcely counted any longer even in the north. All that counted were the generals, the most prominent of whom were: 1) Zhang Zuolin (Chang Tso-lin), a former bandit who had control of Manchuria and had made certain terms with Japan, but who was ultimately murdered by the Japanese (1928); 2)Wu Peifu, who held North China; 3) the so-called "Christian general", Feng Yuxiang, and 4) Cao Kun (Ts'ao K'un), who became president in 1923.

According to the Columbia Encyclopedia: “ Civil war raged between Sun's new revolutionary party, the Kuomintang, which established a government in Guangzhou and received the support of the southern provinces, and the national government in Beijing, supported by warlords (semi-independent military commanders) in the north. As cultural ferment seethed throughout China, intellectuals sought inspiration in Western ideals; Hu Shih, prominent in the burgeoning literary renaissance, began a movement to simplify the Chinese written language. Labor agitation, especially against foreign-owned companies, became more common, and resentment against Western religious ideas grew. Columbia Encyclopedia, 6th ed., Columbia University Press]

Image Sources: Cutting queue, Ohio State University; Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated August 2021