CHIANG KAI-SHEK

Chiang Kai-shek (Jiang Jieshi, 1887-1975) took over as leader of the Kuomintang (Nationalist Party) after the death of Sun Yat-sen (b. 1866) in 1925. As leader of the Kuomintang and, from 1928 until 1949, of China, Chiang Kai-shek inherited, among other things, the role of defining and strengthening Chinese nationalism, a force that he hoped to use to unify the Chinese people behind him and his government.

Chiang Kai-shek (Jiang Jieshi, 1887-1975) took over as leader of the Kuomintang (Nationalist Party) after the death of Sun Yat-sen (b. 1866) in 1925. As leader of the Kuomintang and, from 1928 until 1949, of China, Chiang Kai-shek inherited, among other things, the role of defining and strengthening Chinese nationalism, a force that he hoped to use to unify the Chinese people behind him and his government.

Chiang Kai-shek was a militarist and former warlord who opposed reform but was associated with reform and established a system described as Confucian fascism. One of Sun Yat-sen’s lieutenants from the early revolution days, he was married to Sun's sister-in-law, became the President of Chinese Republic in 1928, battled the Communists for more than two decades, and ruled Taiwan from 1945 until his death in April 1975. Chiang’s name in Mandarin is Jiang Jieshi. Chiang Kai-shek is Yue dialect,

Chiang Kai-shek was regarded as a shrewd politician but a poor administrator. His life was defined by his battle against the Communists which took a variety of forms over the years. In many respect there wasn’t much that separated him from other warlords except they managed to hold on to some kind of power and stay relevant for a long time. Chiang is sometimes called the man who lost China but in reality he never held it to begin with.

In his book "The Generalissimo: Chiang Kai-Shek and the Struggle for Modern China" former U.S. foreign service officer Jay Taylor argues that Chiang was not the corrupt bumbler he was made out to be but rather was “far-sighted, disciplined and canny strategist” who “made the most of the weak hand dealt him.”

In his book "Enter the Dragon: A Look at the Western Fever Dream of Insatiable Chinese Power" Tom Scocca wrote, “Generalissimo Chiang, emerges here as neither a politician nor a military genius but a man with a gift for the sort of politics practiced with armies: warlord politics, in the warlord-ruled aftermath of Qing China. Unfortunately for Chiang, Mao was better at it, and better at ruling the territory he controlled. Chiang's struggle to defeat the Japanese, only to lose the country to the Communists...as the Nationalists fall back from one provisional capital to the next, till they end up off the mainland entirely.]

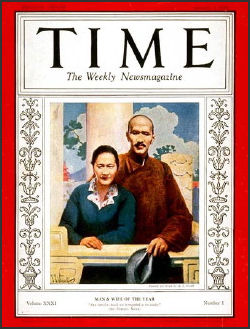

Arthur Waldron, a professor of history at the University of Pennsylvania, wrote in China Brief, “Chiang Kai-she is one of the most important figures in modern China, but also one of the least understood and most regularly caricatured. Chiang unified his country with the Northern Expedition of 1925-29 and presided over the Nanking decade, a period of economic and institutional development as well as considerable freedom that was cut short by the Japanese invasion of 1937. Against that onslaught, Chiang led an indomitable resistance that was arguably China’s finest twentieth century hour, but when the struggle was completed, he gambled on an offensive war to destroy his Communist rivals for power, and lost almost everything...Chiang inspired powerful loyalty among his closest Chinese followers and had Western friends as well, not the least of whom was Henry Luce, publisher of Time magazine. “[Source: Arthur Waldron, a professor of history at the University of Pennsylvania, China Brief (Jamestown Foundation), October 22, 2009]

RELATED ARTICLES IN THIS WEBSITE: REPUBLICAN CHINA, MAO AND THE EARLY COMMUNIST PERIOD factsanddetails.com; REFORMERS, MODERNIZATION AND REFORM EFFORTS IN CHINA IN THE LATE 1800s factsanddetails.com; OBSERVATIONS BY CHINESE ON LIFE IN THE WEST factsanddetails.com; THE 1911 REVOLUTION, SONG JIAOREN AND ATTEMPTS AT DEMOCRACY IN CHINA factsanddetails.com; MAY 4TH MOVEMENT AND THE POLITICAL IDEAS AND REFORMERS ITS SPAWNED factsanddetails.com; KUOMINTANG AND CHINESE WARLORDS factsanddetails.com; SUN YAT-SEN AND REPUBLICAN CHINA factsanddetails.com

Early 20th Century China : John Fairbank Memorial Chinese History Virtual Library cnd.org/fairbank offers links to sites related to modern Chinese history (Qing, Republic, PRC) and has good pictures;

Chiang Kai-shek Wikipedia article Wikipedia Madame Chiang Kai-shek Wikipedia article Wikipedia

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: "The Generalissimo: Chiang Kai-Shek and the Struggle for Modern China" by Jay Taylor Amazon.com; “Victorious in Defeat: The Life and Times of Chiang Kai-shek, China, 1887-1975" by Alexander V. Pantsov, Steven I. Levine - Amazon.com; “Chiang Kai Shek: China's Generalissimo and the Nation He Lost” by Jonathan Fenby Amazon.com; “The Last Empress: Madame Chiang Kai-shek and the Birth of Modern China” by Hannah Pakula Amazon.com; “Soong Dynasty” by Sterling Seagrave Amazon.com; “The Soong Sisters” by Emily Hahn, Nancy Wu, et al. Amazon.com; Amazon.com; “Big Sister, Little Sister, Red Sister: Three Women at the Heart of Twentieth-Century China” by Jung Chang Amazon.com; Film: Soong Sisters Amazon.com “Sun Yat-sen” by Marie-Claire Bergère and Janet Lloyd Amazon.com; “The Unfinished Revolution: Sun Yat-Sen and the Struggle for Modern China” by Tjio Kayloe Amazon.com; “The Birth of a Republic” by Hanchao Lu Amazon.com; “Republican China: Nationalism, War, and the Rise of Communism 1911-1949" by Franz Schurmann and Orville Schell Amazon.com; The Cambridge History of China, Vol. 12: Republican China, 1912-1949, Part 1 by John K. Fairbank Amazon.com; “The Chinese Enlightenment: Intellectuals and the Legacy of the May Fourth Movement of 1919" by Vera Schwarcz Amazon.com; The Cambridge History of China, Vol. 13: Republican China 1912-1949, Part 2 by John K. Fairbank and Albert Feuerwerker Amazon.com; “Penguin History of Modern China: 1850-2009” by Jonathan Fenby Amazon.com;; "China: A New History" by John K. Fairbank Amazon.com

Chiang Kai-shek's Early Life

Young Chiang Kai-shek

Chiang Kai-shek was born in 1887 in a remote village in the eastern province of Zhejiang. The son of a village salt merchant, he was raised by his widowed mother and began working at the age of nine after his father died. When he was 14, he entered an arranged marriage. He later obtained a divorce from wife.

At the age of 18, Chiang left China to train at Tokyo's Military Preparatory Academy. Chiang was impressed by Japanese discipline and sophistication and hoped to bring the same qualities to the Chinese army. He liked the Japanese winters and said that living in Japan gave him a fondness for "eating bitterness."

In 1911, Chiang returned to China and joined the Kuomintang and became a young officer in the new Republic of China army. He became a military aid to Sun Yat-sen but lost his position when Sun was ousted and was forced to seek exile in Japan

Chiang’s rise to power began as a disciple of Sun Yat-sen, founder of the Kuomintang or Nationalist Party, who was supported by the Soviet Union. In 1923, Chiang had spent three months in the USSR consulting, seeking cooperation and addressing the executive committee of the Comintern. In June 1924, he stood beside Sun Yat-sen on the platform as the Whampoa Military Academy, of which he would become superintendent, was opened. It is here that the soon-to-be-victorious Nationalist army was trained. It was made possible by a Russian gift of 2.7 million yuan and a monthly stipend of 100,000 yuan. Chiang Kai-shek’s military academy trained a new generation of officers who would soon embark on the Northern Expedition. Zhou Enlai (1898-1976), who later become premier of China under the communists, was a political commissar at this academy.[Source: Arthur Waldron, a professor of history at the University of Pennsylvania, China Brief (Jamestown Foundation), October 22, 2009]

Chiang Kai-shek’s Character and Background

Chiang Kai-shek was a man full of contradictions. After he converted from Buddhism to Methodism in 1930 he felt the Bible revealed God's plan for China. He said, "To my mind the reason we should believe in Jesus is that He was a leader of a national revolution." Yet, despite his Christian inspirations, he was not shy about using violence or underhanded methods to achieve his objectives. In Shanghai, for example, he hired gangsters from the brutal Green Gang to kill thousands of students and labor organizers with purported ties to the Communists. His ties to corruptions earned him the nickname “General Cash-My-Check.”

Sometimes Chiang Kai-shek lived like a monk and dressed in unadorned military fatigues. He didn’t like Western toilets. He could also be quite extravagant. In Taiwan, he lived in a home with rare Amur leopard skins draped on the walls and a panda skin rug in front of the fireplace.

In a review of "Chiang Kai-shek, The Generalissimo" by Jay Taylor, Perry Anderson wrote in the London Review of Books: Taylor makes a real attempt to capture Chiang’s tortuous personality. Seething with an inner violence that exploded in volcanic rages as a young man, once in power he succeeded in outwardly controlling it beneath a mask so rigid and cold that it isolated him even from his followers. Sexual rapacity was combined with puritan self-discipline, skills in political manoeuvre with bungling in military command, nationalist pride with retreatist instinct, threadbare education with mandarin pretension. ... A better sense of Chiang’s vindictiveness, and of the low-grade thuggishness of his regime, in which torture and assassination were routine, can be gained from Jonathan Fenby’s less inhibited account, Chiang Kai-shek: The Generalissimo and the China He Lost. [Source: Perry Anderson, London Review of Books, February 9, 2012]

"No other figure in the tangled constellation of the interwar Kuomintang acquires any relief in his story. The reasons why Chiang could rise to power require a contextual explanation, however. They do not lie in his individual abilities. For these were, on any reckoning, very limited. The extremes of his psychological make-up cohabited with his mediocrity as a ruler. He was a poor administrator, incapable of properly co-ordinating and controlling his subordinates, and so of running an efficient government. He had no original ideas, filling his mind with dog-eared snippets from the Bible. Most strikingly, he was a military incompetent, a general who never won a really major battle — decisive victories in the Northern Expedition that brought him to power going to other, superior commanders. What distinguished him from these were political cunning and ruthlessness, but not by a great margin. They were not enough on their own to take him to the top. [Ibid]

"The historical reality was that no outstanding leaders emerged from the confused morass of the KMT in the Republican period. The contrast between Nationalists and Communists was not just ideological. It was one of sheer talent. The CCP produced not simply one leader of remarkable gifts, but an entire, formidable cohort, of which Deng was one among several. By comparison, the KMT was a kingdom of the blind. Chiang’s one eye was a function of two accidental advantages. The first was his regimental training in Japan, which made him the only younger associate of Sun Yat-sen with a military background, and so at the Whampoa Academy commanding at the start of his career means of violence that his rivals in Guangzhou lacked. The second, and more important, was his regional background. Coming from the hinterland of Ningbo, with whose accent he always spoke, his political roots were in the ganglands of nearby Shanghai, with its large community of Ningbo merchants. It was this base in Shanghai and Zhejiang, and the surrounding Yangtze delta region, where he cultivated connections in both criminal and business worlds, in what was by far the richest and most industrialised zone in China, that gave him his edge over his peers. The military clique that ruled Guangxi, on the border with Indochina, were better generals and ran a more progressive and efficient government, but their province was too poor and remote for them to be able to compete successfully against Chiang. [Ibid]

Chiang Kai-shek Marries Madame Chiang Kai-shek

Chiangs wedding's

In 1926, a year after he became leader of the Kuomintang, Chiang Kai-shek married Soong Mei-ling, Known to some people as the "Dragon Lady," Soong was born in 1897 in Shanghai. She grew up in Piedmont, Georgia in the United States and graduated from Wellesley College in 1917. Her English was better than her Chinese.

In his diary the American General Joseph Stilwell described her as a “clever, brainy woman....Direct, forceful, energetic. Loves power, eats up publicity and flattery, pretty weak on her history. Can turn on charm at will and knows it.”

In her letters to her American friends, Madame Chiang Kai-shek wrote that her husband had the power and charisma of a military man and the charm and tenderness of a poet, sometimes suprising her with presents of plum blossoms.

Even so Chiang Kai-shek and his wife had a notoriously tempestuous relationship. He converted to Christianity They had no children. Chiang had a son from his first, marriage, who later became leader of Taiwan. Chiang had a second, adopted son, from his second marriage to a woman he chased when he was 32 and she was 13 and who later got a doctorate at Columbia University in New York.

Soong Sisters

Madame Chiang Kai-shek was one of the Soong Sisters. Zhang Kun wrote in the China Daily: “There has never been a trio of sisters more famous in China than the Soongs, The three women - Ai-ling (1888-1973), Ching-ling (1893-1981) and Mei-ling (1898-2003) - are well-known for their key roles in China's political scene throughout the 20th century. Two were once the first ladies of China - Ching-ling married Sun Yat-sen (1866-1925), also known as the Father of Modern China while Mei-ling wedded Chiang Kai-shek (1887-1975), the former leader of the Kuomintang government and president of the Republic of China. The eldest sibling, Ai-ling, was married to Kung Xiang-hsi (1881-1967), the richest man in China in the early 1900s. [Source: Zhang Kun, China Daily, June 3, 2016]

“While Mei-ling and Ai-ling were ardent supporters of the Kuomintang, Ching-ling was steadfast in her Communist beliefs. Despite their differences in ideology, the three sisters nonetheless joined hands to lend vital support to war relief efforts in the fight against Japanese invaders. “In 1940, when the Japanese occupied the capital city of Nanjing, the three reunited in Chongqing and established the Chinese Industrial Cooperatives. The three sisters provided aid to numerous schools, hospitals, air raid shelters and war-torn communities.

It was said of Soong sisters: “One loved money; one loved power; and one loved China.” Madame Chiang Kai-shek was the one who loved power. Soong Ching-ling, the wife of Sun Yat-sen. was the one who loved China. The third sister Soong Ai-ling, who married the banker H.H. Kung, a scion in one of China’s wealthiest banking families, was the one who loved money. The sister’s brother T.V. was an influential politician, serving as the Kuomintang finance minister and prime minister at various times.

See Separate Article: SOONG SISTERS AND MADAME CHIANG KAI-SHEK factsanddetails.com

Revelations from Chiang Kai-shek’s Diary

Chiang, Soong and Chennault

The diaries of Chiang Kai-shek are looked over by research fellow Tai-chun Kuo at the Hoover Institution at Stanford University. "There are many private things," Kuo told Caixin Online. "He wrote about daily life, philosophy, competitors, friends. He was very honest and straightforward. He wrote about how he felt, about how he controlled his sexual desire." [Source: Sheila Melvin, Caixin Online, July 12, 2013 +=+]

Sheila Melvin wrote on Caixin Online, “The diaries reveal a man who appears to have been trying to do what he thought best for his country – even if he wasn't immediately succeeding and the collateral damage was terribly high. They also seem to show that his Christian faith – which has often been seen as a political ploy – was in fact genuine. Many people, including myself, thought Chiang Kai-shek was a fake Christian – that he did it to marry Mei-ling," explained Kuo. "But after we read the diaries none of us questioned it. He read the Bible every day, he copied sentences from the Bible, he mentioned God, he asked for God's help – if not every day, then every other day." On one occasion in 1944, during the battle of Hengyang, Chiang bargained with God, promising in his diary to build the world's largest cross and have it set on Mt. Hengyang, if only God would help him to successfully defend the city. As Kuo explained, "He wrote, 'God, I have tried my best.' Every time when he was suffering, he turned to God." When prayer failed, he even contemplated suicide, suggesting it would be the only alternative if the war were lost; in later years, when the civil war was indeed lost by his side, he criticized himself for being too stubborn, overly confident, and failing to listen to advice. +=+

"Soong Mei-ling, apparently did not understand her husband's obsession with diary writing. She perhaps recognized its dangers and, according to Kuo, believed that "we should go out without leaving any traces, only ashes." But Chiang's decision to keep this long and detailed record of his thoughts – to leave traces - will ultimately enable scholars to further flesh out the caricature he has become, and the historical record along with it. Chiang Kai-shek will never be a hero to anyone, and the list of his errors, miscalculations, and outright wrongs is likely to remain long. But perhaps one day he will be perceived as a man who, in his own words, did his best." +=+

Chiang Kai-shek and the Whampoa Academy

Edward Wong wrote in the New York Times, “It was 1926, not long after the fall of the Qing dynasty, and much of China had been divided among warlords. In the south, leaders of the young Kuomintang mustered an army. At its head rode Chiang Kai-shek, who called to his side officers he had helped train, and together they marched north to take down the warlords, one by one. [Source: Edward Wong, New York Times, December 27, 2012 +++]

“The Northern Expedition was one of the first major tests for graduates of the Whampoa Military Academy, founded just two years earlier on quiet Changzhou Island, about 10 miles east of central Guangzhou, then known to the West as Canton. Mr. Chiang was the academy’s first commandant, appointed by Sun Yat-sen, the idealistic firebrand who wanted to build an army that would unite China. +++

“When Sun Yat-sen founded the Whampoa academy, his goal was to unite China and to revive China as a nation, which is exactly the same mission that Secretary Xi is on,” said Zeng Qingliu, a historian with the Guangzhou Academy of Social Sciences who wrote a television script for a drama series on Whampoa. “Under that goal and that mission, Chinese people from all over the world and across the country were attracted to Whampoa.” +++

“The first class at Whampoa had 600 students, 100 Communists among them, Mr. Zeng said. Prominent Russian advisers worked at the school. Zhou Enlai was the political director, and other famous Communists held posts or trained there. But the school was never under the party’s control. +++

“The Kuomintang moved it to the city of Nanjing in 1927, after a split with the Communists, and then to the southwestern city of Chengdu, after the Japanese occupied Nanjing, then known as Nanking. After the Kuomintang moved to Taiwan, they established a military academy there that they called the successor to Whampoa. But when historians speak of Whampoa, they mean the original incarnation of the school, before it moved from Guangzhou, Mr. Zeng said. Japanese bombs decimated the campus in 1938.” +++

Chiang and Sun Yat-sen at Whampoa

Kuomintang Under Chiang Kai-shek

After Sun Yat-sen's death in 1925, the Kuomintang splintered into competing factions. Chiang Kai-shek allied himself with warlords in southern and central China and emerged as the Kuomintang leader in 1926. He built up his army with the help of the Soviet Union, who regarded the Kuomintang as more progressive than the warlords in the north, and was able to crush the warlords in the north.

Chiang Kai-shek formally became head of the Kuomintang in 1927.In 1928, Chiang led his army from southern China into Beijing. For political ideology he combined Sun's "Three Principles of the People" with his own "New Life Movement," based on Methodist principals.

In December 1931, Chiang’s government collapsed after the Japanese took control Manchuria. Tens of thousands of students rioted in Nanking, taking virtual control of the government there. In Manchuria students demonstrated against the unwillingness of the Chinese army under Chiang to fight the Japanese.

Around the time this was happening Chiang wrote in his journal, “The war with Japan is not a matter of victory or defeat. It’s a matter of life or death for a people and their country” and “our determination will even overcome fate. I’ll wipe out the disgrace” and “we will not think about victory or defeat and national interest. We will sacrifice ourselves to show the class of our country and display national spirit.” Before and during World War II the Kuomintang mounted little resistance against the Japanese.

KMT soldiers needed “marriage report” to get married and could not get married without their superiors' approval. [Source: China Post, July 27, 2014]

China Under Chiang Kai-shek and the Kuomintang

Chiang Kai-shek and the warlord Long Yun

Chiang succeeded Sun Yatsen as the de facto leader of China. He broke with his Soviet advisers and with the communists but by 1927 was successful in defeating the northern warlords and unifying China. The years 1928 to 1937 are often referred to as the Nanjing Decade because of the national development that took place under Chiang’s presidency before World War II when China’s capital was in Nanjing (Southern Capital). The Northern Expedition had culminated in the capture of Beijing, which was renamed Beiping (Northern Peace). Thereafter, the Nanjing government received international recognition as the sole legitimate government of China.

Ordinary Chinese suffered greatly under Kuomintang leadership. Children were forced to work in factories 13 hours a day and sleep by their machines. Women were sold off as concubines and slaves. And magistrates lent money to peasants at outrageously high interest rates so they could buy expensive fertilizers, then lowered the price of the crops at harvest time and seized the land when the peasant couldn't pay back the loans. While Chiang Kai-shek's army warehouses overflowed with grain, people in the Hunan province were starving to death, and eating bark and leaves to survive.

Kuomintang soldiers were largely feared by the general population. Parents feared their daughters would be raped by them when they appeared in town. In some places bowls of urine were placed in houses when the soldiers were around to create a smell so vile no one would want to enter. One elderly woman told the New York Times, “None of the parents wanted to have their older girls at home. When the Nationalist soldiers came...young girls fled to the mountains, cut their hair and covered their faces with dirt.”

Chiang never controlled China, just changing parts of it. In the 1930s, Japan controlled Manchuria, the Communist held much of Shanxi, the Soviet Union controlled Mongolia and Xinjiang, and Europeans held the treaty ports on the coast. In these conditions Chiang moved his government from city to city based largely on which enemy he could strike a deal with.

Chiang attempt to hold the Japanese armies at bay while battling the Communists. After the Japanese launched a full-scale invasion in 1937 he joined forces with Mao and then joined the allies after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor.

During the Rape of Nanking Chiang Kai-skek and his top general escaped from Nanking while ordering Kuomintang troops to defend the city oven though he knew there was little they could do to stop he Japanese advance. Japanese historians have argued that many lives would have been saved had the nationalist army turned over the city to the Japanese .

Chiang Kai-shek and the New Life Movement

Chiang and Dai Li

According to Columbia University’s Asia for Educators: “In 1934, Chiang Kai-shek called for China to carry out a “New Life Movement.” At the time, Chiang was leader of the Republic of China, with his government in Nanjing. Chiang’s government, seriously underfunded, had only nominal control over vast areas of the country, which were actually run by warlords who had allied with Chiang and acknowledged the authority of his ROC government in theory while retaining substantial power (backed by their own armies) in practice. Chiang’s government was notoriously corrupt and not averse to cooperating with organized crime on projects such as opium “suppression” (i.e., monopoly), kidnapping, and assassination of political enemies. Japan had taken over northeastern China, or Manchuria, in 1932-1933 and renamed it “Manchukuo.” Within China, intellectuals had debated (and attacked) traditional Chinese values in the New Culture or May Fourth Movement, and the Communist Party, although driven underground in the cities, was active in the countryside. [Source: Asia for Educators, Columbia University, Primary Sources with DBQs, afe.easia.columbia.edu ]

“Chiang Kai-shek heralded the "New Life Movement" to rally the Chinese people against the Communists and build up morale in a nation that was besieged with corruption, factionalism, and opium addiction. Rather than turning away from Confucian values as did the May 4 Movement, Chiang Kai-shek used the Confucian notion of self-cultivation and correct living for this movement. Here we see an attempt to revitalize what was seen by Chiang as the "essence" of being Chinese.” It was in this context that Chiang Kai-shek delivered his “Essentials of the New Life Movement” speech.

See Chiang Kai-shek, 1887-1975 "Essentials of the New Life Movement" (Speech, 1934) [PDF] afe.easia.columbia.edu

Chiang Kai-shek Taken Prisoner During the Xian Incident

In 1932, taking advantage of divisions in China, the Japanese established the puppet state of Manchukuo in Manchuria. While Japan moved southward from Manchuria, Chiang chose to campaign against the Communists rather the the Japanese. In the "Xi'an Incident" in December, 1936, Chiang was kidnapped by Nationalist troops from Manchuria and held until he agreed to accept Communist cooperation in the fight against Japan. [Source: Columbia Encyclopedia, 6th ed., Columbia University Press]

On December 12, 1936, a year after the Long March, Chiang Kai-shek was taken prisoner by his own generals at Hua Qing Pool, a Tang Dynasty resort near Xian. In what later became known as the Xian Incident, Chiang was taken, reportedly wearing only pajamas, after a Manchurian general named Zhang Xueiling (General Chang) — who wanted Chiang to turn his attention form fighting the Communists to fighting the Japanese — made a deal with Zhou Enlai for the Communists and Kuomintang to cease hostilities and unite against the Japanese.

According to one story Chiang was held for two weeks before he escaped by jumping out of window. In truth, Chiang met with Communist and Manchurian leaders and endorsed the deal made by Zhang and Zhou, bringing a temporary end of the Civil War. The deal was reportedly worked out by Madame Chiang who arrived in Xian 11 days after her husband was captured and managed to sweet talk Zhang into setting him free within 48 hours. Chiang was released by Zhang who was later arrested and imprisoned by Chiang who never forgave him. Zhang remained in a Taiwan jail until 1992, seventeen years after Chiang's death.

A few months later, Chiang maneuvered the Manchurian troops out of the Xian area and was getting ready to make a move on the Communists when the Japanese mounted a massive invasion in 1937 and Chiang was forced to cancel his plans and defend his territory against the Japanese.

Xian Incident

Zhang Xueliang

Zhang Xueliang was the eldest son of Zhang Zuolin, a warlord who ruled parts of northeast China. After his father was assassinated by the Japanese in 1928, Zhang swore allegiance to the Nationalist government. Although he fought against the Communists, he contributed to uniting China’s forces against Japan in the Xian Incident. After being court-martialed for kidnapping Chiang Kai-shek, Zhang was kept under house arrest in several locations in China and Taiwan. He regained his freedom around 1990 and later emigrated to Hawaii. He is regarded as a “hero of history” in China.

Kiyota Higa wrote in the Yomiri Shimbun, “Zhang Xueliang, who in 1936 was instrumental in forging a united front between the Kuomintang (Chinese Nationalist Party) and Communists to fight the Japanese, spent more than 10 years under house arrest in the sleepy mountain village of Hsinchu, northern Taiwan. In what is now known as the Xian Incident, Zhang, then a Kuomintang general, helped kidnap the party’s leader, Chiang Kai-shek. Zhang later spent nearly 50 years under house arrest, first in mainland China and later in Taiwan. [Source: Kiyota Higa, Yomiri Shimbun, July 4, 2013]

In 1946, Zhang was moved to this village from Chongqing, the Nationalist government’s wartime base in mainland China. “Tossing and turning, I could not sleep. Tears dry slowly on my pillow,” Zhang wrote. He filled his time writing poetry, in addition to reading and gardening. A statue of Zhang reading as an old man stands in one of the house’s tatami rooms.

"China Cannot Be Conquered”: 1939 Speech by Chiang Kai-shek

According to Columbia University’s Asia for Educators: “Chiang Kai-shek inherited, among other things, the role of defining and strengthening Chinese nationalism, a force that he hoped to use to unify the Chinese people behind him and his government. The speech below on national unity was delivered by Chiang in January 1939 when China was in a full.scale war with Japan. [Source: Asia for Educators, Columbia University, Primary Sources with DBQs, afe.easia.columbia.edu ]

Chiang and Mao toasting Japan's defeat in 1945

In his “China Cannot Be Conquered” speech, Chiang Kai-shek said: “We are fighting this war [against the Japanese] for our own national existence and for freedom to follow the course of national revolution laid down for us in the Three Principles of the People. … You [high.level Kuomintang officials] should instruct our people to take lessons from the annals of the Song and Ming dynasties. [Source: "China Cannot Be Conquered" (Speech, 1939) by Chiang Kai-shek from “Chinese Civilization: A Sourcebook”, edited by Patricia Buckley Ebrey, 2nd ed. (New York: The Free Press, 1993), 401-406; Asia for Educators, Columbia University, Primary Sources with DBQs, afe.easia.columbia.edu ]

The fall of these two dynasties [to the Mongols and the Manchus, both non-Chinese] was not caused by outside enemies with a superior force, but by a dispirited and cowardly minority within the governing class and society of the time. Today the morale of our people is excellent. … Our resistance is a united effort of government and people. … Concord between government and people is the first essential to victory. “The hearts of our people are absolutely united.”

Dai Li: Chiang Kai-shek’s Favorite Assassin

Dai Li (also known as Dai Yunong) was China’s most accomplished assassin during the War of Resistance against Japan. He took out some of Chiang Kai-shek’s most troublesome enemies and bedded with some of the most glamorous women of his day. Born Dai Chunfeng in Zhejiang Province’s Jiangshan City in 1897, he began training at the Whampoa Military Academy in Guangzhou, where he met Chiang Kai-shek. Among Dai’s nicknames were “Chiang Kai-shek’s Personal Saber”, “China’s Global Bodyguard”, “China’s Himmler”, and “China’s Most Mysterious Man”.[Source: Kevn McGeary, China Channel, LARB, March 22, 2019]

Kevn McGeary wrote: In May 1933 in Beijing’s Grand Hotel, Dai personally assassinated Zhang Jingyao, a fearsome warlord who tried to help the Japanese set up a puppet Manchu government. In June of the same year he was responsible for assassinating the democratic activist Yang Xingfo. In 1934 he killed the celebrity journalist Shi Liangcai and Communist Party member Ji Hongchang. From 1937 onwards, Dai Li would often carry out reconnaissance work in the most dangerous occupied territory. In January 1938, he was involved in trapping and killing Shandong Governor Han Fuju, who was suspected of colluding with the Japanese to spare his province and position. In March of the same year, he was part of the unsuccessful assassination attempt on Wang Kemin, who would later commit suicide while on trial for treason.

"In February 1939 he assassinated Chen Lu, foreign affairs minister of the puppet government, in Shanghai. In March of the same year Dai was sent on a special mission to Hanoi to assassinate Chiang Kai-shek’s political rival and Japanese collaborator Wang Jingwei. Wang survived the bullet wound but died in Japan in 1944 when receiving treatment for an infection caused by it, avoiding a likely execution for treason. In August 1940 he shot to death Zhang Xiaolin, leader of notorious Shanghai criminal organization The Green Gang, and in October of the same year he stabbed to death Shanghai’s puppet mayor Fu Xiao’an.

"After the attack on Pearl Harbor (which Dai had accurately predicted) he was invited to collaborate with American intelligence agencies. In 1943, Dai was behind the successful poisoning of Li Shiqun, who had defected from the Communist Party to the Chiang Kai-shek’s Guomindang (KMT) and later headed the No. 76 Spy Organization, which became notorious for torturing their political enemies. In January 1944, Dai was behind the bombing of a Japanese-occupied coal mine in Hebei. When the war ended in 1945, he began a campaign to arrest suspected traitors throughout the country.

"As well as being a feared assassin, Dai was also a notorious lothario. His lovers included actress Hu Die, one of the most famous beauties of the era. However, the woman who brought out his softer side was Chen Hua, whom he affectionately knew as “Huamei.” Chen Hua was sold as a concubine at age 13, and at 16 she married Yang Hu, Sun Yat-sen’s Shanghai garrison commander. Dai met her on a train in 1932 and was enchanted by her beauty. He tried to arrange for his student Ye Xiazhui (the wife of General Hu Zongnan) to be her assistant, but Chen saw what he was up to and refused."

Chiang Kai-skek’s Bad Rap and General Stilwell

Sheila Melvin wrote on Caixin Online, “ Chiang was put into impossible military and political positions by an unreliable Washington and the cantankerous “Vinegar Joe” Stilwell, the American general in China, who once referred to Chiang as ‘Peanut.’ “It is well known that Stilwell detested Chiang Kai-shek....This was not only because of the shape of his head, which have rise to the "Peanut" moniker, but because Stilwell regarded Chiang as a "little person." Chiang's diaries seem to reveal that he was oblivious to Stilwell's disdain. "When Stilwell arrived in Chongqing in March 1942, Chiang Kai-shek opened his arms. He saw himself as senior and was willing to educate Stilwell – he told him to be patient and consult, to learn from the experiences of Chinese generals." In his diary, Chiang noted, "I gave Stilwell lessons." Stilwell, however, in his own diary – also in Hoover Institution archives – wrote, "Peanut gave me lessons – bullshit." [Source: Sheila Melvin, Caixin Online, July 12, 2013]

In World War II, Chiang was accused of caring little for ordinary Chinese and getting others to fight his battles so he could conserve his forces to fight the Communists after the war. Arthur Waldron wrote: "The negative picture of Chiang can to a certain extent be traced back to one man, the American General Joseph W. Stilwell, whom Roosevelt sent to advise Chiang, and who soon came to despise him. Stilwell, not called Vinegar Joe for nothing... Stilwell was himself the poor strategist: for example, now that we have all the documentation, it is clear that the American four star gravely under-estimated the Japanese in Burma (Myanmar), throwing away tens of thousands of troops in the ill-judged and failed Myitkina offensive. Chiang’s inclination to hold to the defensive was clearly prudent and would have been a better course of action. [Source: Arthur Waldron, a professor of history at the University of Pennsylvania, China Brief (Jamestown Foundation), October 22, 2009]

Chiang, Soong and Stilwell

"A second wellspring of anti-Chiang sentiment was the unhappy American attempt, led by General George C. Marshall, to bring internal peace to post-War China by creating a coalition government between Chiang’s Nationalists and Mao Zedong’s Communists which foundered for many reasons, one of which was that Marshall had great leverage over Chiang, who depended upon the United States for support, but none whatsoever over the Communists, who were amply supplied by Moscow. Marshall never fully understood this fact, nor did many others. The American ambassador, Leighton Stuart, for example, who had lived in China for decades as an educator and was fluent in the language, believed that ties between the Chinese Communists and Moscow were tenuous and insignificant.

In a review of "Chiang Kai-shek, The Generalissimo" , Perry Anderson wrote in the London Review of Books: Central to The Generalissimo is the aim of reversing the verdict of Barbara Tuchman’s book on the American role, personified by General Stilwell, in the Chinese theatre of the Pacific War. For Taylor, it wasn’t the long-suffering Chiang, but the arrant bully and incompetent meddler Stilwell who was to blame for disputes between the two, and failures in the Burma campaign. Stilwell was no great commander. Taylor documents his abundant failings and eccentricities well enough. But they scarcely exonerate Chiang from his disastrous sequence of decisions in the war against Japan, many of them — even at the height of the fateful Ichigo offensive of 1944 — motivated by his conviction that Communism was the greater danger. From the futile sacrifice of his best troops in Shanghai and Nanjing in 1937 to the gratuitous burning of Changsha in 1944, it was a story without good sense or glory. Despite strenuous scrubbings by recent historians to blanco his military record, it is no surprise that, from a position of apparent overwhelming strength after the surrender of Japan, he crumpled so quickly against the PLA in the Civil War. [Source: Perry Anderson, London Review of Books, February 9, 2012]

“There too Taylor tends to attribute to the US substantial blame for the debacle — Marshall, who had picked Stilwell, cutting a not much better figure in this part of his narrative — which he hints could have been avoided had Washington been willing to provide the massive support needed to help Chiang hold North China or, failing that, a line south of the Yangtze. These are not the sentiments of the Republican lobby that denounced the “loss of China” in the 1950s. Taylor has an independent mind. Describing himself as a moderate liberal and foreign policy pragmatist, he is quite capable of scathing criticism of US policies in full support of Chiang — attacking the “breathtaking” irresponsibility of Eisenhower in threatening war with the PRC during the Quemoy crisis of 1955, and composing with Dulles a secret policy document on the same island three years later, “extraordinary for its ignorant and far-fetched analysis.” What remains constant, however, is the American visor through which Chinese developments are perceived.

"Taylor concludes his story with the claim that Chiang has triumphed posthumously, since the China of today embodies his vision for the country, not that of the Communists he fought. This trope is increasingly common. Fenby retails a lachrymose variant of it, quite out of character with the rest of his book, a tourist guide in the PRC — as good as a taxi-driver for any passing reporter — telling him what an unnecessary tragedy KMT defeat in the Civil War was. In such compensation fantasies, Deng becomes Chiang’s executor, and Western visions of what China should be, and will become, are reassured.

Image Sources: Chiang Kai shek, Ohio State University; Chiangs wedding, wikipedia ; Soong sisters, wikipedia; 5) Soong Sisters film ; Kuomintang army, wikipedia

Text Sources: Asia for Educators, Columbia University afe.easia.columbia.edu; New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated August 2021