LIFE DURING THE HAN DYNASTY (206 B.C. - 220 A.D.)

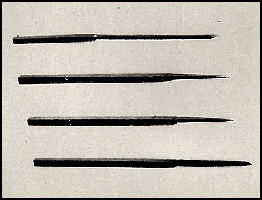

Accupuntcure needles found in

the Tomb of Liu Sheng Looking good and wearing make up appears to have been highly valued based on the number of cosmetic boxes found in the graves of Han women. Small vessels featured acrobats doing stunts; figures playing the board game Liud; and tomb murals depicting partygoers, jugglers, musicians and dancers seems indicate entertainment was also valued. In A.D. 2, a rhinoceros from an unidentified country was delivered to China. It was a bit hit in the court of the emperor. Eight years later an ostrich was delivered. It too was a big hit.

Confucian customs like respect towards elders were strictly enforced while women's rights were ignored. There was one law that stated that any wife who beat a grandfather was to be chopped to death in the marketplace. Slandering an old person was also a serious offense, but beating a wife wasn't even a crime.

Accupuncture needles and figurines with meridian lines drawn on them have been found, indicating that some form of acupuncture was practiced. Clasped hands was a sign of greeting. People who addressed the emperor were allowed to do so only after their breath has been sweetened with “odoriferous pistols”— Javanese cloves.

The rich clearly lived a privileged life, enjoying concubines, servants, slaves, pearls, jade and fine clothes One observer wrote that people in Luoyang “are extravagant in clothing, excessive in food and drink... Rich men convicted of a crime could hire peasants to fulfill their sentences. Over time, peasants were squeezed off their land and many became unhappy indentured servants, increasing the likelihood of a rebellion.

RELATED ARTICLES IN THIS WEBSITE: ZHOU, QIN AND HAN DYNASTIES factsanddetails.com; HAN DYNASTY (206 B.C.-A.D. 220) factsanddetails.com; LIU BANG AND THE CIVIL WAR THAT BROUGHT THE HAN TO POWER factsanddetails.com; HAN DYNASTY RULERS factsanddetails.com; EMPEROR WU DI factsanddetails.com; WANG MANG: EMPEROR OF THE BRIEF XIN DYNASTY factsanddetails.com; RELIGION AND IDEOLOGY DURING THE HAN DYNASTY factsanddetails.com; CONFUCIANISM DURING THE EARLY HAN DYNASTY factsanddetails.com; CULTURE, ART, SCIENCE AND LITERATURE DURING THE HAN DYNASTY (206 B.C. - 220 A.D.) factsanddetails.com; HAN DYNASTY GOVERNMENT factsanddetails.com; HAN DYNASTY ECONOMY factsanddetails.com

Good Websites and Sources: Han Dynasty Wikipedia ; Early Chinese History: 1) Robert Eno, Indiana University indiana.edu; 2) Chinese Text Project ctext.org ; 3) Visual Sourcebook of Chinese Civilization depts.washington.edu ;

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: “Daily Life in Ancient China” by Mu-chou Poo Amazon.com; “Life in Ancient China” by Paul Challen Amazon.com ; “Early Chinese Religion” edited by John Lagerwey & Marc Kalinowski (Leiden: 2009) Amazon.com; “Age of Empires: Art of the Qin and Han Dynasties” by Zhixin Sun, I-tien Hsing Amazon.com; “Tomb Treasures: New Discoveries from China's Han Dynasty” by Jay Xu Amazon.com; “The Organization of Imperial Workshops during the Han Dynasty” by Dr. Anthony Jerome Barbieri-Low Amazon.com; "The Cambridge Illustrated History of China" by Patricia Buckley Ebre Amazon.com

Han Era Houses

sculpture of a stove

There are few remains of Han-era houses except for their foundations but what houses were like at that time can be ascertained from models of houses buried with dead. Archaeology magazine reported: “Since the beginning of the twentieth century, many mingqi (a word that literally means "visible objects," used to mean all types of grave furnishings) have been discovered in Han Dynasty tombs in Henan Province. A particularly impressive one is a two-meter-tall model of a seven-story manor house dated to the A.D. first century. [Source: Archaeology magazine,Volume 64 Number 1,January-February 2011; Qinghua Guo, “The Mingqi Pottery Buildings of Han Dynasty China (206 B.C.–A.D. 220): Architectural Representations and Represented Architecture”, Sussex Academic Press, 2010.]

“Actual remains of ancient Chinese domestic architecture are rare. Scholars, however, are still able to glean the appearance of some types of houses from pottery modelsthat reveal a higher level of architectural achievement than had previously been imagined. From the carefully constructed main house and tower with its brightly colored exterior, to the enclosed courtyard with its model dog, the level of detail shown in this mingqi is impressive. The artist even inscribed small markings on the home's exterior, both to sign his work and to help him assemble the model.

“Many Han Dynasty tombs were equipped with the necessities of everyday life including furniture, cooking utensils, and even food — items thought to provide comfort and ease the soul's transition to the afterlife. Mingqi as elaborate as this, however, would only have been buried with the wealthiest members of Han society. The manor house model was discovered in 1993 in Tomb no. 6 at Baizhuang, Jiaozuo, Henan Province. It is currently located in the Henan Museum, China.

Posthouses and Communications in the Han Dynasty

The Xuanquan Posthouse (50 kilometers east of Duanhuang in Gansu Province) refers to the remains of an important courier station in the Hexi Corridor built in the Han Dynasty (206 B.C. - A.D. 220) in the Gobi desert to the north of Huoyan Hill, which is an offshoot of Qilian mountains. A large number of Chinese documents written in bamboo and wooden slips from Han Dynasty were unearthed there, recording the postal system in the large transportation system of the Han Empire. These documents provided information on how transportation and communication was carried out along the Silk Roads. [Source: silkroad.org.cn]

The main function of the Xuanquan Posthouse to help relay a variety of mail, cummunications and information and provide lodging for passing messengers, officials, official personnel and foreign guests. The site of Xuanquan Posthouse covers an area of 22,500 square meters in which 4675 square meters have been excavated. The site contains complete architectural community remains of the Han Dynasty, including Wubao (fortress), stables, houses and auxiliary buildings outside the fortress and sites of beacon towers in the northwest corner of the Wei and Jin dynasties (3-4 century AD). Han Dynasty Post Road remainswere discovered 20 meters north of the north wall. The Wubao takes up a square area of 50 meters × 50 meters and faces east. On the northeast and the southwest corners of the square are turret ruins, surrounded by other architectural sites. The site of stables is located outside the south wall of the Wubao. More than 70,000 cultural relics have been excavated, mostly bamboo and wooden slips, silk manuscripts, paper-based documents, silk, calendars, stationery, lacquer ware, bronze ware, barley, alfalfa and other crops, as well as bones of horses, camels and other animals.

The slips document the passing horses and carts and the official settings, with descriptions of sealing, delivery and receipt of mails and records of diplomatic missions. Messengers from Asian territories such Uisin, Ferghana, Loulan, Khotan and Kucha in what is now western China and Central Asia and places further west such as Kapisa, Alexandra Prophthasia and Rouzhi, Qangly, Jiyue, and Junqi Phi Ogak. All this gives an idea of how extensive the Han Dynasty postal system and communications were. Xuanquan Posthouse faced the Shule River and Great Wall of the Han Dynasty and was connected with the Xuanquan Spring of Xuanquan Valley, showing how ancient posthouses relied on provision support from towns and rivers and how people of that time utilized nature to cross the Gobi desert.

Food and Drink in the Han Dynasty

The Book of Rites, a Chinese history book compiled in the Western Han Dynasty (202 B.C.-9), put melons, apricots, plums and peaches among the 31 categories of food favored by aristocrats of the time.

In May, 2011, Chinese scientists announced they had found 2000-year-old wine in Henan province. Wang Hanlu wrote in the People's Daily, “A Western Han dynasty ancient tomb group was accidentally found at a construction site in Puyang city, China’s Henan province, on April 10. After a period of protective excavation of the tomb group, archaeologists found more than 230 ancient tombs in all, and a total of more than 600 cultural relics have been unearthed so far. During the excavation, archaeologists discovered an airtight copper pot covered in rust. They found the pot had a liquid weighing about half a kilogram in it. On May 10, the Beijing Mass Spectrum Center, which is a joint accrediting body based on the Chinese Academy of Science, identified the liquid in the ancient pot as wine. [Source: Wang Hanlu, People's Daily Online, May 11, 2011]

In August 2014, archeologists announced they discovered a 2,100-year-old mausoleum built for a king named Liu Fei in present-day Xuyi County in Jiangsu, China. In the tomb was a kitchen with food for the afterlife. Livescience.com reported: “Archaeologists found an area in the burial chamber containing bronze cauldrons, tripods, steamers, wine vessels, cups and pitchers. They also found seashells, animal bones and fruit seeds. Several clay inscriptions found held the seal of the “culinary officer of the Jiangdu Kingdom.”“ [Source: livescience.com, August 16, 2014]

In the late 2010s, archaeologists unearthed a bronze kettle containing liquor from a Qin Dynasty (221–206 B.C.) tomb that dates back to just before the Han . China.org reported: “The kettle is a sacrificial vessel. It was among among 260 items unearthed from a graveyard of commoners’ tombs from the Qin Dynasty (221-207 B.C.). Most of the relics were for worshiping rituals. Xu Weihong, a researcher with the provincial archeological institute, said about 300 ml of liquor was found in the kettle, which had its opening sealed with natural fibers. The liquor is a transparent milky white. Researchers believed it was made using fermentation techniques, as it was composed of glutamic acid substances. [Source: China.org.cn, May 5, 2018]

Chinese Emperors Living Far From the Sea Enjoyed Sea Snails and Clams

In October 2010, Chinese scientists announced that ancient Chinese emperors living in inland China may have dined on seafood that came from the eastern China coast more than 1,600 kilometers after investigating an imperial mausoleum that dates back 2,000 years. “We discovered the remains of sea snails and clams among the animal bone fossils in a burial pit,” Hu Songmei, a Shaanxi Provincial Institute of Archaeology researcher told Xinhua. “Since the burial pit appears to be that of the official in charge of the emperor’s diet, we conclude that seafood must have been part of the imperial menu,” Hu said. [Source: Zhang Xiang, Xinhua, October 30, 2010 \=]

Xinhua reported: The discovery was made in the Hanyang Mausoleum in the ancient capital of Chang’an, today’s Xi’an City in northwest China’s Shaanxi Province. The monument is the joint tomb of Western Han Dynasty (202 B.C.- A.D. 8) Emperor Jing and his empress. Archaeology at the mausoleum began in the 1980s. Since 1998, researchers from the Shaanxi Provincial Institute of Archaeology have been excavating the burial pit east of the mausoleum. \=\

“Of the 43 animal fossils discovered in the pit, archaeologists found more than 18 kinds of animals, including three kinds of sea snails and one kind of clam. “The ancient people believed in the afterlife. They thought the dead could possess what they had when they were alive,” said Hu. Many royal tombs were designed and constructed like the imperial palace. The burial pits usually represented different departments of the imperial court, Hu said. “The discovery of animal fossils in this particular pit may shed light on what the emperor ate everyday.” Ge Chengyong, the chief editor of Chinese Culture Relics Press, said, “The seafood may have been tribute offered to the emperor by imperial family relatives living on the Chinese coast. It may also have been businessmen that brought them inland to the capital city.” \=\

“Xi’an is more than one thousand miles away from the Chinese coast, so how could it have arrived in the capital without first spoiling? “During the Qin Dynasty (221-206 B.C.), Chinese people used vehicles with refrigeration,” said Ge. “It is thought they may have put ice in the vehicles to preserve perishable cargo.” “The seafood may also have been dried before it was transported,” Ge added. \=\

“Alongside the fossilized seafood shells, fossils of various other kinds of animals — rabbit, fox, leopard, sheep, deer, cat and dog — were also discovered. Hu said, “The cat was kept in the imperial kitchen to catch rats, and so the other animals were all part of the imperial diet.” “Ancient Chinese people valued diversity in their diet. The imperial diet would have include multiple nutrients, multiple flavors and a vast number of dishes.” “Just from the animal fossils discovered so far, we cannot know the whole story of the emperor’s diet. There will be more findings.” \=\

2,000-Year-Old Ice Box Found in North-Central China

model of a pig pen

In May 2011, archeologists in Shaanxi Province announced they found a primitive “icebox” that dated back at least 2,000 years ago in the ruins of a temporary imperial residence of the Qin Dynasty (221 B.C. – 207 B.C.). The “icebox”, in the shape of a shaft 1.1 meters in diameter and 1.6 meters tall, was unearthed about 3 meters underground in the residence.

Xinhua reported: “The "icebox," unearthed in Qianyang county, contained several clay rings 1.1 meters in diameter and 0.33 meters tall, said Tian Yaqi, a researcher with the Shaanxi Provincial Institute of Archeology. "The loops were put together to form a shaft about 1.6 meters tall," Tian said. [Source: Xinhua, May 26, 2010 |+|]

“The shaft was unearthed about 3 meters underground within the ruins of an ancient building which experts believed was a temporary imperial residence during the Qin Dynasty (221 - 207 B.C.). "The shaft led to a river valley, but it could not have been a well," said Tian. A well, he explained, would have been much deeper as groundwater could not have been reached only 3 meters underground in arid northwest China. "Nor would it have been possible to build a well inside the house." |+|

“Tian and his colleagues believe the shaft was an ice cellar, known in ancient China as "ling yin," a cool place to store food during the summer. A poem in the "Book of Songs" - a collection of poetry from the Western Zhou Dynasty (11th century -771 B.C.) to the Spring and Autumn Period (770 - 475 B.C.) - says food kept in the "ling yin" will to stay fresh for three days in the summer. "If ice cellars were popular more than 2,000 years ago, it certainly sounds reasonable that the emperor and court officials would have one in their residence," said Tian. Covering an area of about 22,000 square meters, the shaft and the residence were first discovered by villagers building homes in 2006. The area was immediately fenced off by authorities to protect the heritage site.” Research work began in March 2010 and ended in May the same year. |+|

World’s Oldest Tea — 2,150 Years Old — Found in Xian Emperor’s Tomb

tea leaves

In January 2016, archaeologists announced they had discovered the oldest tea in the world (2,150 years old) among the treasures buried with a Chinese emperor in Xian and in a tomb in Tibet. Archaeology magazine reported: The finds contain traces of caffeine and theanine — substances particularly characteristic of tea. The tombs are more than 2,000 years old, indicating the beverage was consumed during the Han Dynasty (206 B.C.–A.D. 220). A Chinese document from 59 B.C. that mentions a drink that might be tea was previously the earliest known record of the beverage. Tea does not grow near the tombs, so the discovery indicates that the Silk Road was a “much more complicated and complex long-distance trade network than was known from written sources,” says researcher Dorian Fuller, an archaeobotany professor at University College London. Tea-producing regions, including remote areas of China and even Myanmar, he adds, had “well established supply lines” feeding into the Silk Road. [Source: Lara Farrar, Archaeology magazine, May-June 2016]

David Keys wrote in The Independent, “New scientific evidence suggests that ancient Chinese liked tea so much that they insisted on being buried with it – so they could enjoy a cup of char in the next world. The new discovery was made by researchers from the Chinese Academy of Sciences and published in Nature’s online open access journal Scientific Reports. “Previously, no tea of that antiquity had ever been found – although a single ancient Chinese text from a hundred years later claimed that China was by then exporting tea leaves to Tibet. By examining tiny crystals trapped between hairs on the surface of the leaves and by using mass spectrometry, they were able to work out that the leaves, buried with a mid second century B.C. Chinese emperor, were actually tea. The scientific analysis of the food and other offerings in the Emperor’s tomb complex have also revealed that, as well as tea, he was determined to take millet, rice and chenopod with him to the next life. [Source: David Keys, The Independent, January 10, 2016 -]

“The tea aficionado ruler – the Han Dynasty Emperor Jing Di – died in 141 B.C., so the tea dates from around that year. Buried in a wooden box, it was among a huge number of items interred in a series of pits around the Emperor’s tomb complex for his use in the next world. Other items included weapons, pottery figurines, an ‘army’ of ceramic animals and several real full size chariots complete with their horses. -

“The tomb, located near the Emperor Jing Di’s capital Chang’an (modern Xian), can now be visited. Although the site was excavated back in the 1990s, it is only now that scientific examination of the organic finds has identified the tea leaves. The tea-drinking emperor himself was an important figure in early Chinese history. Often buffeted by intrigue and treachery, he was nevertheless an unusually enlightened and liberal ruler. He was determined to give his people a better standard of living and therefore massively reduced their tax burden. He also ordered that criminals should be treated more humanely – and that sentences should be reduced. What’s more, he successfully reduced the power of the aristocracy. -

“The tea discovered in the Emperor’s tomb seems to have been of the finest quality, consisting solely of tea buds – the small unopened leaves of the tea plant, usually considered to be of superior quality to ordinary tea leaves. “The discovery shows how modern science can reveal important previously unknown details about ancient Chinese culture. The identification of the tea found in the emperor’s tomb complex gives us a rare glimpse into very ancient traditions which shed light on the origins of one of the world’s favourite beverages,” said Professor Dorian Fuller, Director of the International Centre for Chinese Heritage and Archaeology, based in UCL, London.” -

Everyday Items from Han Dynasty Tombs

According to the National Palace Museum, Taipei: “During the Ch'in and Han, bronze and jade objects were still considered valuables reserved for the upper echelons of society. The sword, knife, seal, and jade ornaments, as well as a bronze mirror, were what a gentleman would carry on him.” Everyday objects used by people of different classes include “vessels for cooking food, such as "ting", "tseng", and "yen"; containers for drinks, such as "tsun", "ho", "hu" and cups; water vessels, such as "chien" and "p'an"; lamps for providing light; "po-shan" censers for making the air fragrant; and sheep-shaped weights for holding things down. [Source: National Palace Museum, Taipei \=/ ]

model well

Patricia Buckley Ebrey of the University of Washington wrote: “ In 1968 two tombs were found in present-day Mancheng County in Hebei province (review map). The first undisturbed royal Western Han tombs ever discovered, they belong to the prince Liu Sheng (d. 113 B.C.), who was a son of Emperor Jing Di, and Liu Sheng's consort Dou Wan. For the first time images of daily life began to appear in tombs in the form of wall reliefs and earthenware models. Before this time, representations of scenes from life had been rare, a minor artistic concern when compared to the interest in shapes and surface decoration. In the tombs at Mancheng, however, the bronzes are mostly unadorned vessels meant for everyday use. [Source: Patricia Buckley Ebrey, University of Washington, depts.washington.edu/chinaciv /=]

Liu Sheng's tomb contained over 2,700 burial objects. Among them, bronze and iron items predominate. Altogether there were: A) 419 bronze objects; B) 499 iron objects; C) 21 gold items; D) 77 silver items; E) 78 jade objects; F) 70 lacquer objects; G) 6 chariots (in south side-chamber); H) 571 pieces of pottery (mainly in north side-chamber); I) silk fabric; J) gold and silver acupuncture needles (length: 6-7 centimeters); J) an iron dagger (length: 36.4 centimeters width: 6.4 centimeters); K) three bronze leopards inlaid with gold and silver plum-blossom designs; L) bronze weights (height: 3.5 centimeters, length: 5.8 centimeters; M) a bronze ding with two ears fitted with movable animal-shaped pegs to keep the cover tight; N) a double cup with a bird-like creature in the center that holds a jade ring in its mouth and its feet are planted on another animal. /=\

There was also a bronze incense burner inlaid with gold (height: 26 centimeters). According to Ebrey: “Three dragons emerge from the openwork foot to support the bowl of the burner. The bowl is decorated with a pattern of swirling gold inlay suggestive of waves. The lid of the burner is formed of flame-shaped peaks, among which are trees, animals, and immortals. There are many tiny holes in the peaks. Oil-burning lamps were a common means of night-time illumination in this and later periods. A bronze lamp (height: 48 centimeters) has an ingenious movable door to regulate the supply of oxygen and thus the strength of the fire. Smoke from the fire would go up the sleeve, keeping the room from getting too smoky.” /=\

2,100-Year-Old King’s Mausoleum

In August 2014, archeologists announced they discovered a 2,100-year-old mausoleum built for a king named Liu Fei in present-day Xuyi County in Jiangsu, Liu Fei died in 128 B.C. during the 26th year of his rule over a kingdom named Jiangdu, which was part of the Chinese empire. Livescience.com reported: “Although the mausoleum had been plundered, archaeologists found that it still contained more than 10,000 artifacts, including treasures made of gold, silver, bronze, jade and lacquer. They also found several life-size chariot and dozens of smaller chariots. [Source: livescience.com, August 16, 2014, The journal article was originally published, in Chinese, in the journal Kaogu, by archaeologists Li Zebin, Chen Gang and Sheng Zhihan. It was translated into English by Lai Guolong and published in the journal Chinese Archaeology +++]

brick depicting wine brewing

“Excavated between 2009 and 2011, the mausoleum contains “three main tombs, 11 attendant tombs, two chariot-and-horse pits, two weaponry pits” and the remains of an enclosure wall that originally encompassed the complex, a team of Nanjing Museum archaeologists said in an article recently published in the journal Chinese Archaeology. The wall was originally about 1,608 feet (490 meters) long on each side. A large earthen mound — extending more than 492 feet (150 meters) — once covered the king’s tomb, the archaeologists say. The tomb has two long shafts leading to a burial chamber that measured about 115 feet (35 meters) long by 85 feet (26 meters) wide. Sadly, the king’s coffins had been damaged and the body itself was gone. “Near the coffins many jade pieces and fragments, originally parts of the jade burial suit, were discovered. These pieces also indicate that the inner coffin, originally lacquered and inlaid with jade plaques, was exquisitely manufactured,” the team writes. +++

“A second tomb, which archaeologists call “M2,” was found adjacent to the king’s tomb. Although archaeologists don’t know who was buried there it would have been someone of high status. Although it was looted, archaeologists still discovered pottery vessels, lacquer wares, bronzes, gold and silver objects, and jades, about 200 sets altogether,” the team writes. The ‘jade coffin’ from M2 is the most significant discovery. Although the central chamber was looted, the structure of the jade coffin is still intact, which is the only undamaged jade coffin discovered in the history of Chinese archaeology,” writes the team. +++

“In addition to the chariot models and weapons found in the king’s tomb, the mausoleum also contains two chariot-and-horse pits and two weapons pits holding swords, halberds, crossbow triggers and shields. In one chariot-and-horse pit the archaeologists found five life-size chariots, placed east to west. “The lacquer and wooden parts of the chariots were all exquisitely decorated and well preserved,” the team writes. Four of the chariots had bronze parts gilded with gold, while one chariot had bronze parts inlaid with gold and silver. The second chariot pit contained about 50 model chariots. “Since a large quantity of iron ji (Chinese halberds) and iron swords were found, these were likely models of battle chariots,” the team writes. +++

“A series of 11 attendant tombs were found to the north of the king’s tomb. By the second century B.C. human sacrifice had fallen out of use in China so the people buried in them probably were not killed when the king died. Again, the archaeologists found rich burial goods. One tomb contained two gold belt hooks, one in the shape of a wild goose and the other a rabbit. Another tomb contained artifacts engraved with the surname “Nao.” Ancient records indicate that Liu Fei had a consort named “Lady Nao,” whose beauty was so great that she would go on to be a consort for his son Liu Jian and then for another king named Liu Pengzu. Tomb inscriptions suggest the person buried in the tomb was related to her, the team says. +++

“About seven years after Liu Fei’s death, the Chinese emperor seized control of Jiangdu Kingdom, because Liu Jian, who was Liu Fei’s son and successor, allegedly plotted against the emperor. Ancient writers tried to justify the emperor’s actions, claiming that, in addition to rebellion, Liu Jian had committed numerous other crimes and engaged in bizarre behavior that included having a sexual orgy with 10 women in a tent above his father’s tomb.” +++

Items in 2,100-Year-Old King’s Tombs Offer Hints Of Han-Era Life

Han emperors and noblemen commonly decorated their tombs with pottery replicas of warriors, concubines, servants, horses, domestic animals, trees, plants, furniture, models of towers, granaries, mortars and pestles, stoves and toilets, and almost everything found in the real world so the deceased would have everything he needed in the next world.

Livescience.com reported: “When archaeologists entered the burial chamber they found that Liu Fei was provided with a vast assortment of goods for the afterlife. Such goods would have been fitting for such a “luxurious” ruler. “Liu Fei admired daring and physical prowess. He built palaces and observation towers and invited to his court all the local heroes and strong men from everywhere around,” wrote ancient historian Sima Qian (145-86 B.C.), as translated by Burton Watson. “His way of life was marked by extreme arrogance and luxury.” [Source: livescience.com, August 16, 2014 +++]

“His burial chamber is divided into a series of corridors and small chambers. The chamber contained numerous weapons, including iron swords, spearheads, crossbow triggers, halberds (a two-handled pole weapon), knives and more than 20 chariot models (not life-size). The archaeologists also found musical instruments, including chime bells, zither bridges (the zither is a stringed instrument) and jade tuning pegs decorated with a dragon design. +++

“Liu Fei’s financial needs were not neglected, as the archaeologists also found an ancient “treasury” holding more than 100,000 banliang coins, which contain a square hole in the center and were created by the first emperor of Chinaafter the country was unified. After the first emperor died in 210 B.C., banliang coins eventually fell out of use. In another section of the burial chamber archaeologists found “utilities such as goose-shaped lamps, five-branched lamps, deer-shaped lamps, lamps with a chimney or with a saucer ….” They also found a silver basin containing the inscription of “the office of the Jiangdu Kingdom.” +++

“The king was also provided with a kitchen and food for the afterlife. Archaeologists found an area in the burial chamber containing bronze cauldrons, tripods, steamers, wine vessels, cups and pitchers. They also found seashells, animal bones and fruit seeds. Several clay inscriptions found held the seal of the “culinary officer of the Jiangdu Kingdom.” +++

Wang Zhaojun: One of the Four Beauties of China

Wang Zhaojun

Wang Zhaojun, also known as Wang Qiang, was born in Baoping Village, Zigui County (in current Hubei Province) in 52 B.C. in the the Western Han Dynasty (206 B.C.– A.D. 8). One of the Four Great Beauties of Ancient Chinese, she is said to have been a gorgeous lady and talented at painting, Chinese calligraphy, playing chess and music. She lived at a time when the Han Empire was having conflicts with Xiongnu, a nomadic people from Central Asia based in present-day Mongolia. Before her life took a dramatic turn, she was a neglected palace concubine, never visited by the emperor.

In 33 B.C., Hu Hanye, leader of the Xiongnu paid a respectful visit to the Han emperor, asking permission to marry a Han princess, as proof of the Xiongnu people's sincerity to live in peace with the Han people. Instead of giving him a princess, which was the custom, the emperor offered him five women from his harem, including Wang Zhaojun. No princess or maids wanted to marry a Xiongnu leader and live a distant place so Wang Zhaojun stood out when she agreed to go to Xiongnu.

The historical classic, "Hou Han Shu", reveals that Wang Zhaojun volunteered to marry Hu Hanye. When the Han emperor finally met her, he was astonished by her beauty, but it was too late for regrets. She married Hu Hangye and had children by him. Her life became the foundation and unfailing story of "Zhaojun Chu Sai", or "Zhaojun Departs for the Frontier". Peace ensued for over 60 years thanks to her marriage. [Source: Peng Ran, CRIENGLISH.com, July 17, 2007]

In the most prevalent version of the "Four Beauties" legend, it is said that Wang Zhaojun left her hometown on horseback on a bright autumn morning and began a journey northward. Along the way, the horse neighed, making Zhaojun extremely sad and unable to control her emotions. As she sat on the saddle, she began to play sorrowful melodies on a stringed instrument. A flock of geese flying southward heard the music, saw the beautiful young woman riding the horse, immediately forgot to flap their wings, and fell to the ground. From then on, Zhaojun acquired the nickname "fells geese" or "drops birds." Statistics show that there are about 700 poems and songs and 40 kinds of stories and folktales about Wang Zhaojun from more than 500 famous writers, both ancient (Shi Chong, Li Bai, Du Fu, Bai Juyi, Li Shangyin, Zhang Zhongsu, Cai Yong, Wang Anshi, Yelü Chucai) and modern (Guo Moruo, Cao Yu, Tian Han, Jian Bozan, Fei Xiaotong, Lao She, Chen Zhisui). [Source: Wikipedia +]

The mausoleum of Wang Zhaojun is called Qing Zhong, or the Green Tomb. It resembles the natural green slope of a hill. She is still commemorated in Inner Mongolia people as a peace envoy, who contributed greatly to the friendship between the Han and Mongolian ethnic groups. A Zhaojun Museum has been set up near her tomb, in which her beautiful likeness is displayed in a white-marble sculpture and her wedding scene has become a bronze statue. In these artistic representations Wang Zhaojun always looks happy and resolved, in accordance with the widely accepted image of her as a brave woman who sacrificed for her country. Her sorrows as a tragic heroine deprived of true love may be buried along with her deep in the green tomb.

For more on Wang Zhaojun see: FOUR BEAUTIES OF ANCIENT CHINA factsanddetails.com

Same Sex Love In Han Dynasty China

Sarah Prager wrote in Jstor Daily: “In the last years BCE, Emperor Ai was enjoying a daytime nap. He was in his palace, in Chang’an (now Xi’an, China), hundreds of miles inland, wearing a traditional long-sleeved robe. Lying on one of his sleeves was a young man in his 20s, Dong Xian, also asleep. So tender was the emperor’s love for this man that, when he had to get up, instead of waking his lover, he cut off the sleeve of his robe. This story of the cut sleeve spread throughout the court, leading the emperor’s courtiers to cut one of their own sleeves as tribute. The tale’s influence outlived its time, producing the Chinese term “the passion of the cut sleeve,” a euphemism for intimacy between two men.[Source: Sarah Prager, Jstor Daily, June 10, 2020]

“Emperor Ai was far from the only Chinese emperor to take a male companion openly. In fact, a majority of the emperors of the western Han dynasty (206 BCE to 220 CE) had both male companions and wives. The historian Bret Hinsch asserts in Passions of the Cut Sleeve: The Male Homosexual Tradition in China that all ten emperors who ruled over the first two centuries of the Han dynasty were “openly bisexual,” with Ai being the tenth. They each had a “male favorite” who is listed in the Records of the Grand Historian (the “Shiji”) and the Book of Han (the “Hanshu”).

“Hinsch quotes the Shiji: “Those who served the ruler and succeeded in delighting his ears and eyes, those who caught their lord’s fancy and won his favor and intimacy, did so not only through the power of lust and love; each had certain abilities in which he excelled.” Sima Qian, the author of the Shiji, who also wrote “The Biographies of the Emperors’ Male Favorites,” continues (as quoted by Hinsch): “It is not women alone who can use their looks to attract the eyes of the ruler; courtiers and eunuchs can play that game as well. Many were the men of ancient times who gained favor this way.”

“Emperor Gao favored Jiru. Emperor Hui favored Hongru. Emperor Jing, Zhou Ren. And Emperor Zhao, Jin Shang. These rulers were also married to women, but their male companions were important parts of their lives as well. Thanks to detailed records that have survived two millenia, we know that these favorites received great privilege and power in exchange for their intimacy. Ai bestowed Dong Xian with the highest titles and ten thousand piculs of grain per year. Everyone in Dong Xian’s family benefitted from the emperor’s patronage; Dong Xian’s father was named the marquis of Guannei and everyone in Dong Xian’s household, including his slaves, received money. Dong Xian and his wife and children were all moved inside the imperial palace grounds to live with Emperor Ai and his wife.

“According to medical anthropologist Vincent E. Gil, writing in the Journal of Sex Research, China had “a long history of dynastic homosexuality” before the Revolution of 1949, with “courtly love among rulers and subjects of the same sex being elevated to noble virtues.” He says that the surviving literature from that time period in China “indicates that homosexuality was accepted by the royal courts and its custom widespread among the nobility.” Writing in the Journal of the History of Sexuality, James D. Seymour agrees that relationships between men were “widely accepted and sometimes formalized by marriage,” adding that “almost all of the emperors of the last two centuries B.C. had ‘male favorites.’”

Hinsch asserts that “not only was male love accepted, but it permeated the fabric of upper-class life” during Emperor Ai’s time. Since marriage was divorced from romance in this culture and time period, and primarily represented the union of two families, “a husband was free to look elsewhere for romantic love and satisfying sex. Even in the ancient period, we see men who maintained a heterosexual marriage and a homosexual romance without apparently seeing any contradiction between the two.” When Emperor Ai died in 1 BCE, he wanted to leave the kingdom to his beloved Dong Xian. Unfortunately, the court considered this display of favoritism one step too far. They ignored the emperor’s deathbed decree and forced Dong Xian and his wife to kill themselves. It was the end of the Western Han dynasty.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Robert Eno, Indiana University /+/ ; Asia for Educators, Columbia University afe.easia.columbia.edu ; University of Washington’s Visual Sourcebook of Chinese Civilization, depts.washington.edu/chinaciv /=\; National Palace Museum, Taipei \=/; Library of Congress; New York Times; Washington Post; Los Angeles Times; China National Tourist Office (CNTO); Xinhua; China.org; China Daily; Japan News; Times of London; National Geographic; The New Yorker; Time; Newsweek; Reuters; Associated Press; Lonely Planet Guides; Compton’s Encyclopedia; Smithsonian magazine; The Guardian; Yomiuri Shimbun; AFP; Wikipedia; BBC. Many sources are cited at the end of the facts for which they are used.

Last updated August 2021