PORTS AND SHIPPING IN CHINA

Yellow River animal skin raft China has 7,700 kilometers of navigable waterways (2020), 6th in the world. Merchant marine: total: 6,662, third in the world. By type: bulk carrier 1,558, container ship 341, general cargo 957, oil tanker 1,061, other 2,745 (2021). The merchant marine fleet in 2005 consisted of 1,649 ships of 1,000 gross registered tons (GRT) or more, for a total of over 18.7 million GRT carried. [Source: CIA World Factbook, 2022 =; Junior Worldmark Encyclopedia of the Nations, Thomson Gale, 2007]

Ports and terminals

Major seaports: Dalian, Ningbo, Qingdao, Qinhuangdao, Shanghai, Shenzhen, Tianjin

Container ports (TEUs): Dalian (8,760,000), Guangzhou (23,236,200), Ningbo (27,530,000), Qingdao (21,010,000), Shanghai (43,303,000), Shenzhen (25,770,000), Tianjin (17,264,000) (2019)

LNG terminals (import): Fujian, Guangdong, Jiangsu, Shandong, Shanghai, Tangshan, Zhejiang

river port: Guangzhou (Pearl) =

China has more than 2,000 ports, 130 of which are open to foreign ships. The major ports, including river ports accessible by ocean-going ships, are Beihai, Dalian, Dangdong, Fuzhou, Guangzhou, Haikou, Hankou, Huangpu, Jiujiang, Lianyungang, Nanjing, Nantong, Ningbo, Qingdao, Qinhuangdao, Rizhao, Sanya, Shanghai, Shantou, Shenzhen, Tianjin, Weihai, Wenzhou, Xiamen, Xingang, Yangzhou, Yantai, and Zhanjiang. Additionally, Hong Kong is a major international port serving as an important trade center for China. In 2005 Shanghai Port Management Department reported that its Shanghai port became the world’s largest cargo port, processing cargo topping 443 million tons and surpassing Singapore’s port. As of 2004, China’s merchant fleet had 3,497 ships. Of these, 1,700 ships of 1,000 gross registered tons (GRT) or more totaled 20. 4 million tons. In 2003 China’s major coastal ports handled 2.1 billion tons of freight.

Seven of the world’s ten largest container ports are in China. The the world's busiest container ports by total number of actual twenty-foot equivalent units (TEUs) transported through the port (rank, and container traffic in thousand TEUs) in 2011, 2010 , 2009 , 2008 , 2007 , 2006 , 2005 , 2004):

1) Shanghai: 31,740, 29,069, 25,002, 27,980, 26,150, 21,710, 18,084, 14,557;

2) Singapore: 29,940, 28,431, 25,866, 29,918, 27,932, 24,792, 23,192, 21,329;

3) Hong Kong: 24,380, 23,699, 20,983, 24,248, 23,881, 23,539, 22,427, 21,984;

4) Shenzhen, China: 22,570, 22,510, 18,250, 21,414, 21,099, 18,469, 16,197, 13,615;

5) Busan, South Korea: 16,170, 14,194, 11,954, 13,425, 13,270, 12,039, 11,843, 11,430;

6) Ningbo-Zhoushan, China: 14,720, 13,144, 10,502, 11,226, 9,349, 7,068, 5,208, 4,006;

7) Guangzhou, China: 14,260, 12,550, 11,190, 11,001, 9,200, 6,600, 4,685, 3,308;

8) Qingdao, China: 13,020, 12,012, 10,260, 10,320, 9,462, 7,702, 6,307. +

Also See Pirates Under Crime, Government and Shipbuilding, Under Industry, Economics

Chinese Trade and Shipping

Most of China’s exports are carried by ship. Some is carried to Russia and Europe by the Trans-Siberian Railroad. Shipping costs between Shanghai and New York are double those between Shanghai and Hamburg and ten times those between Shanghai and Osaka. It takes about 14 days for a container ship to travel from Hong Kong to California. Freight carried to Europe takes 40 days by ship and 15 days by the Trans-Siberian Railroad.

Most of the goods exported from China are transported by container ships. The largest of these ships are 397-meter-long, weight 70,000 tons, are 56 meters wide, 61 meters high and 30 meters deep and can carry 11,000 twenty-foot containers, enough to fill a 44-mile-long train. A patented lashing system is used secure the containers. Around a thousand refrigerators containers and their power supply can be accommodated. Although they only need a crew of 13 they often carry up to 30 people. The ships are powered by 14-cylinder diesel engines that produces 80,000 kilowatts of power and can propel the ships to speeds of 25.5 knots. The anchors weigh 29.4 tons.

Ships that leave China fully loaded with containers often return empty or nearly empty. For every 100 containers that cross the Pacific from Asia to North America only 60 return full, compared to 84 in 1996. Those that return often transport goods at a steep discount to get clients to use the service. Some are outfitted with cardboard and wooden planks so they can carry grain. Some shippers find it more profitable to return empty to China quickly rather than taking on cheap, time-wasting cargo.

See Separate Article CHINESE TRADE: WORLD ECONOMY, CONTAINER SHIPS AND THE WTO See Separate Article factsanddetails.com

Maritime Shipping in China

During the early 1960s, China's merchant marine had fewer than thirty ships. By the 1970s and 1980s, maritime shipping capabilities had greatly increased. In 1985 China established eleven shipping offices and jointly operated shipping companies in foreign countries. In 1986 China ranked ninth in world shipping with more than 600 ships and a total tonnage of 16 million, including modern roll-on and roll-off ships, container ships, large bulk carriers, refrigerator ships, oil tankers, and multipurpose ships. The fleet called at more than 400 ports in more than 100 countries. [Source: Library of Congress, 1987 *]

In 1985 the transportation system handled 2.7 billion tons of goods. Of this waterways handled 434 million tons; ocean shipping handled 65 million tons. The 1985 volume of passenger traffic was 428 billion passenger-kilometers. Of this, waterway traffic, for 17.4 billion passenger-kilometers; In the 1980s, the maritime fleet made hundreds of port calls in virtually all parts of the world, but the inadequate port and harbor facilities at home still caused major problems. Ownership and control of the different elements of the transportation system varied according to their roles and their importance in the national economy. The merchant fleet was operated by the China Ocean Shipping Company (COSCO), a state-owned enterprise.

Transportation was designated a top priority in the Seventh Five-Year Plan (1986-90). Port construction also was listed as a priority project in the plan. The combined accommodation capacity of ports was to be increased by 200 million tons, as compared with 100 million tons under the Sixth Five-Year Plan (1981-85).

The container ship fleet also was expanding rapidly. In 1984 China had only fifteen container ships. Seven more were added in 1985, and an additional twenty-two were on order. By the early 1980s, Chinese shipyards had begun to manufacture a large number of ships for their own maritime fleet. The China Shipping Inspection Bureau became a member of the Suez Canal Authority in 1984, empowering China to sign and issue seaworthiness certificates for ships on the Suez Canal and confirming the good reputation and maturity of its shipbuilding industry. In 1986 China had 523 shipyards of various sizes, 160 specialized factories, 540,000 employees, and more than 80 scientific research institutes. The main shipbuilding and repairing bases of Shanghai, Dalian, Tianjin, Guangzhou, and Wuhan had 14 berths for 10,000-ton-class ships and 13 docks.*

The inadequacy of port and harbor facilities has been a longstanding problem for China but has become a more serious obstacle because of increased foreign trade. Beginning in the 1970s, the authorities gave priority to port construction. From 1972 to 1982, port traffic increased sixfold, largely because of the foreign trade boom. The imbalance between supply and demand continued to grow. Poor management and limited port facilities created such backups that by 1985 an average of 400 to 500 ships were waiting to enter major Chinese ports on any given day. The July 1985 delay of more than 500 ships, for instance, caused huge losses. All of China's major ports are undergoing some construction. To speed economic development, the Seventh Five-Year Plan called for the construction by 1990 of 200 new berths — 120 deep-water berths for ships above 10,000 tons and 80 medium-sized berths for ships below 10,000 tons — bringing the total number of berths to 1,200. Major port facilities were developed all along China's coast.*

According to the Worldmark Encyclopedia of Nations: “China's merchant fleet expanded from 402,000 gross registered tonnage (GRT) in 1960 to over 10,278,000 GRT in 1986, and to 18,724,653 GRT in 2005. China's 1,649 merchant ships of 1,000 GRT or over can accommodate most of the country's foreign trade. The balance is divided among ships leased from Hong Kong owners and from other foreign sources. The principal ports are Tianjin, the port for Beijing, which consists of the three harbors of Neigang, Tanggu, and Xingang; Shanghai, with docks along the Huangpu River channel; Lüda, the chief outlet for the northeast and the Daqing oil field; and Huangpu, the port for Guangzhou, on the right bank of the Pearl River. Other important ports include Qinhuangdao; Qingdao; Ningbo, the port for Hangzhou; Fuzhou; Xiamen; and Zhanjiang. [Source: Worldmark Encyclopedia of Nations, Thomson Gale, 2007]

COSCO

China Ocean Shipping (Group) Company, known as COSCO or COSCO Group, is a Chinese shipping and logistics services supplier company. Headquartered at Ocean Plaza in the Xicheng District in Beijing, the company owns more than 130 vessels (with a capacity of 600,000 twenty-foot equivalent units (TEU)) and calls on over a thousand ports worldwide. Globally, it ranks sixth largest in number of container ships and ninth largest in aggregate container volume. Cosco should not to be confused with Costco, the popular shopping chain..[Source: Wikipedia]

COSCO contains seven listed companies and has more than 300 subsidiaries locally and abroad, providing services in freight forwarding, ship building, ship repair, terminal operation, container manufacturing, trade, financing, real estate, and information technology. It owns and operates a fleet of around 550 vessels, with total carrying capacity of up to 30 million metric tons deadweight (DWT).

COSCO was founded on April 27, 1961. It is a state-owned enterprise and a public company traded on the Stock Exchange of Hong Kong (SEHK). Key people include Wei Jiafu, Chairman and CEO. COSCO is the largest dry bulk carrier in China and one of the largest dry bulk shipping operators worldwide. In addition, the Group is the largest liner carrier in China.

Old Chinese Boats, Sampans and Rafts

Yangtze river boat

The world's oldest boats — dated to 8000-7000 years ago — have been found in Kuwait and China. One of the oldest boats was found in China's Zhejiang province in 2005 and was believed to date back about 8,000 years.

Sampans are traditional Chinese houseboats. They are associated mostly with southern China and have traditionally been used by fishermen who lived with their families and worked from their boats.

People in the western provinces of Ningxia, Qinghai and Gansu still use inflatable animal skin rafts as ferries to cross the Yellow River and other rivers. Traditionally made by Muslim Hui craftsmen, the rafts are made from the skins of sheep, goats and sometimes cattle, which have been soaked in oil and brine for several days before they are inflated.

A medium-size raft is composed of a dozen or so skins tied together under a wooden frame. A raft of this size is strong enough to transport four or five people and their bicycles. Single skin rafts which can accommodate one or two people are used for short ferry rides (the skin reportedly only holds air for about 15 minutes with passengers on board). Forty-by-twenty-five foot rafts made of 600 sheepskins were used in the 1950s on the 1,600-mile, two-week journey on the Yellow River between Lanzhou and Baotou. Few of animal-skin rafts are used anymore. They and their Muslim builders have largely been displaced by bridges.

Junks

The junk is a kind of Chinese ship first used in the 4th century B.C. The hull has traditionally been paneled with teak and the sails have traditionally been made of cloth or reed mats stiffened by bamboo battens. A junk has no keel. Instead it has a deep and sturdy rudder that turns the vessel and helps keep it stable in strong winds. A junk employs as many as five masts that support square lugsails that can spread and close like Venetian blinds.

Some of the largest ships in historical times were junks. A typical ocean-going junk in Marco Polo's time was a 100 feet long and had four masts, oars that required four men to pull and a dozen or so sails made of bamboo slats that rattled in the wind. Teak was prized in shipbuilding because it was strong and resistant to sea worms. It was harvested in forest in India and Southeast Asia. See ZHENG HE'S EXPEDITIONS factsanddetails.com

The technique for leak-proof partitions of Chinese junks was placed on List of Intangible Cultural Heritage in Need of Urgent Safeguarding in 2010. According to UNESCO: Developed in South China’s Fujian Province, the watertight-bulkhead technology of Chinese junks permits the construction of ocean-going vessels with watertight compartments. If one or two cabins are accidentally damaged in the course of navigation, seawater will not flood the other cabins and the vessel will remain afloat. The junks are made mainly of camphor, pine and fir timber, and assembled through use of traditional carpenters’ tools. They are built by applying the key technologies of rabbet-jointing planks together and caulking the seams between the planks with ramie, lime and tung oil. The construction is directed by a master craftsman who oversees a large number of craftsmen, working in close coordination. Local communities participate by holding solemn ceremonies to pray for peace and safety during construction and before the launch of the completed vessel. The experience and working methods of watertight-bulkhead technology are transmitted orally from master to apprentices. However, the need for Chinese junks has decreased sharply as wooden vessels are replaced by steel-hulled ships, and today only three masters can claim full command of this technology. Associated building costs have also increased owing to a shortage in raw materials. As a result, transmission of this heritage is decreasing and transmitters are forced to seek alternative employment. [Source: UNESCO]

Inland Waterways in China

Inland navigation is China's oldest form of transportation. In the 1980s waterborne transportation dominated freight traffic in east, central, and southwest China, along the Chang Jiang (Yangtze River) and its tributaries, and in Guangdong Province and Guangxi-Zhuang Autonomous Region, served by the Zhu Jiang (Pearl River) system.

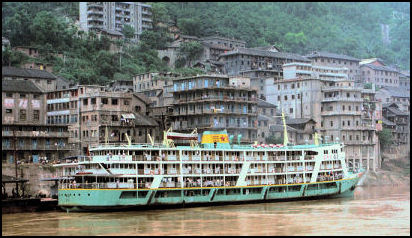

China has more than 140,000 kilometers of navigable rivers, streams, lakes, and canals, and in 2003 these inland waterways carried nearly 1.6 trillion tons of freight and 6.3 trillion passenger/kilometers to more than 5,100 inland ports. The main navigable rivers are the Heilongjiang; Yangzi; Xiangjiang, a short branch of the Yangzi; and Zhujiang. Ships of up to 10,000 tons can navigate more than 1,000 kilometers on the Yangzi as far as Wuhan. Ships of 1,000 tons can navigate from Wuhan to Chongqing, another 1,286 kilometers upstream. The Grand Canal is the world’s longest canal at 1,794 kilometers and serves 17 cities between Beijing and Hangzhou. It links five major rivers: the Haihe, Huaihe, Huanghe, Qiantang, and Yangzi.

Despite the potential advantages of water transportation, it was often mismanaged or neglected in the past. Beginning in 1960 the network of navigable inland waterways decreased further because of the construction of dams and irrigation works and the increasing sedimentation. But by the early 1980s, as the railroads became increasingly congested, the authorities came to see water transportation as a much less expensive alternative to new road and railroad construction. The central government set out to overhaul the inefficient inland waterway system and called upon localities to play major roles in managing and financing most of the projects. By 1984 China's longest river, the Chang Jiang, with a total of 70,000 kilometers of waterways open to shipping on its main stream and 3,600 kilometers on its tributaries, became the nation's busiest shipping lane, carrying 72 percent of China's total waterborne traffic. An estimated 340,000 people and 170,000 boats were engaged in the water transportation business. More than 800 shipping enterprises and 60 shipping companies transported over 259 million tons of cargo on the Chang Jiang and its tributaries in 1984. Nationally, in 1985 the inland waterways carried some 434 million tons of cargo. In 1986 there were approximately 138,600 kilometers of inland waterways, 79 percent of which were navigable. [Source: Library of Congress, 1987 *]

The Cihuai Canal in northern Anhui Province opened to navigation in 1984. This 134-kilometer canal linking the Ying He, a major tributary of the Huai He, with the Huai He's main course, had an annual capacity of 600,000 tons of cargo. The canal promoted the flow of goods between Anhui and neighboring provinces and helped to develop the Huai He Plain, one of China's major grainproducing areas.*

According to the Worldmark Encyclopedia of Nations: About 25 percent of the of navigable inland waterways are navigable by modern vessels, while wooden junks are used on the remainder. The principal inland waterway is the Yangtze River. Much work was done in the early 1980s to dredge and deepen the river, to improve navigational markers and channels, and to eliminate the treacherous rapids of the Three Gorges section east of Yibin. Steamboats can now travel inland throughout the year from Shanghai, at the river's mouth, upstream as far as Yibin, and 10,000ton oceangoing vessels can travel inland as far as Wuhan in the high-water season and Nanjing in the low-water season. Major ports on the river include: Chongqing, the principal transportation hub for the southwest; Wuhan, its freight dominated by shipments of coal, iron, and steel; Wuhu, a rice-exporting center; Yuxikou, across the river from Wuhu and the chief outlet for the region's coal fields; Nanjing; and Shanghai. The Pearl River is navigable via a tributary as far as Nanning. The ancient Grand Canal, rendered impassable by deposits of silt for more than 100 years, has been dredged and rebuilt; it is navigable for about 1,100 kilometers (680 miles) in season and 400 kilometers (250 miles) year-round. [Source: Worldmark Encyclopedia of Nations, Thomson Gale, 2007]

Boat Travel in 19th Century China

Arthur Henderson Smith wrote in “Chinese Characteristics”: “Chinese ferry boats are unprovided with any proper gangway planks, but are furnished with a miserable assortment of narrow and crooked boards,' over which it is next to impossible for an animal to walk. The philosopher who was told that his straitened apartments did not seem large enough to " swing a cat in," aptly replied that he did not wish to " swing a cat." The ferry-man is not open to criticism for not having planks over which mules and donkeys will walk, for he does not wish them to do so. What he does wish, and will most surely achieve, is that whoever has occasion to take animals over the river shall be obliged to hire some of the idlers who are always at hand in such places to help him get his live-stock aboard the venerable ark which does duty as a ferry-boat. [Source:“Chinese Characteristics” by Arthur Henderson Smith, 1894]

The so-called "Grand Canal" is at present largely disused from the lack of water, and is crossed on bridges of boats. But as this simple means of transit would abolish the profits arising from narrow and crooked planks leading to a ferry, a happy compromise has been adopted, by which the rotten old planks are so disarranged as to lead to the boats, and offer almost as much obstruction as those of a ferry, requiring the unharnessing of the whole team and the labour of several men to do what ought not to need doing at all. Sometimes ferry-men will conduct the traveller to an island in the middle of a river, and refuse to take him any further, unless the rest of the channel is considered as a new and distinct river, for which an additional price is to be paid. If the river is to be crossed by fording, there are always vagrants in the vicinity who insist upon being employed to lead the animals across. However shallow the stream may be, it is more necessary to secure their services than at first sight appears, for it often happens that they warn you of holes the extistence of which no one would suspect, and which have been purposely dug by themselves to break the legs of the animals of such travellers are refuse to submit to the demands of these guides.

“Travellers on the Peiho river, between Tientsih and Peking, have sometimes noticed in the river little flags, and upon inquiry have ascertained that they indicated the spots where torpedoes had been planted, and that passing boats were expected to avoid them!

Barge Travel on the Grand Canal

The Grand Canal is largest ancient artificial waterway in the world and an engineering marvel on the scale of the Great Wall of China. Begun in 540 B.C. and completed in A.D. 1327, it is 1,107 miles long and has largely been dug by hand by a work force described as a "million people with teaspoons." At its peak the Grand Canal extended from Tianjin in the north to Hangzhou in the south. It connected Beijing and Xian in the north with Shanghai in the south, and linked four great rivers—the Yellow, the Yangtze, Huai and Qiantang

Ian Johnson wrote in National Geographic:“Grand Canal barges have no fancy names, no mermaids planted on the bow, no corny sayings painted on the stern. Instead they have letters and numbers stamped on the side, like the brand on a cow. Such an unsentimental attitude might suggest unimportance, but barges plying the Grand Canal have knit China together for 14 centuries, carrying grain, soldiers, and ideas between the economic heartland in the south and the political capitals in the north. [Source: Ian Johnson, National Geographic, May, 2013]

“Outside the northern city of Jining, Zhu Silei—Old Zhu, as everyone calls him—fired up the twin diesels on Lu-Jining-Huo 3307, his shiny new barge. It was 4:30 a.m., and Old Zhu had hoped to get a jump on the other crews, who were still toying with their anchors. But as I gazed at the shore, I noticed that the trees had stopped moving against the graying sky. Looking out the other window, I was surprised to see barges overtaking us. Just then the radio crackled to life. “Old Zhu, what’s up with you?” a barge captain said, laughing. “You missed the channel!”

“We had run aground. Old Zhu narrowed his eyes in disgust. He had spent six months on land supervising his barge’s construction and now in his haste had underestimated the Grand Canal, with its challenging currents and its channels that silt up. Grudgingly, he picked up the mike and asked for advice. After hearing that the sandbar was small, he stared intently at the water and decided on quick action. He reversed hard, pushing the throttle to full. The diesels shook the 165-foot barge and its thousand metric tons of coal with a mighty shudder. He spun the wheel, flipped the gear, and gunned the engines again. The waters churned as we surged ahead. With trailing lights off to save power, and the water lit only by the moon, Lu-Jining-Huo 3307 was like a Uboat heading into enemy territory. Our target: Nantong, 430 miles to the south.

“Old Zhu had taken on huge debt. His barge has a capacity of 1,200 metric tons, but the global economic slowdown meant that the coal broker in Jining had only 1,100 tons to offer. And instead of getting 70 yuan ($11) a ton, as Old Zhu had before, he’d now get 45. That meant his gross revenue for this trip would be 49,500 yuan ($7,500). He’d burn about 24,500 yuan’s worth of diesel and pay more than 10,000 yuan in canal fees. On top of that there would be fines for everything from discharging wastewater to having the wrong kind of lighting. If he did well, he’d clear 5,000 yuan. But that was before the interest payment on his barge. To finance it, Old Zhu had borrowed 840,000 yuan from loan sharks at 15 percent. For this trip alone the interest would amount to 10,500 yuan. Overall, Lu-Jining-Huo 3307’s maiden voyage would probably lose him about 5,000 yuan. But Old Zhu was betting that the world recession bottomed out in 2009, when he started building his barge, and that steel prices would climb, making his boat look cheap compared to ones yet to be built. He also believed that coal prices would rebound. “I’ll lose money for five years but then be fine,” he said, with the conviction of a Wall Street trader with a very long position on the world economy.

See Separate Article GRAND CANAL OF CHINA factsanddetails.com; WATER PROJECTS AND CANALS IN ANCIENT AND IMPERIAL CHINA factsanddetails.com

Chuanmin: People of Grand Canal

Ian Johnson wrote in National Geographic:“Canal people, known as chuanmin, re-create village life on their $100,000 barges. Like farmers at harvest time, the small crews—generally just one family—start at dawn and go till evening, when they tie up their boats next to each other. Old Zhu’s wife, Huang Xiling, now posted at the stern, had given birth to the family’s two sons on earlier barges. She cooked, cleaned, and made the boat’s little cabin a retreat from the water, wind, and sun. “The men say these boats are just a tool for making money, but our lives are spent on them,” she said. “You have so many memories.” [Source: Ian Johnson, National Geographic, May, 2013]

“The couple’s older son, Zhu Qiang, had recently taken over their previous barge. Their other son, 19-year-old Zhu Gengpeng, Little Zhu, was working on this new one, being groomed by his dad to be a captain. Little Zhu took me under his wing, translating his father’s incomprehensible Shandong accent and making sure I didn’t fall over the side. Gracing my quarters with his calligraphy, he wrote the words “Private Berth” above the watertight door. (My berth was a storeroom that had been converted into a guest suite by laying a plank and a quilt across two empty paint drums.)

“Little Zhu doesn’t look much like a chuanmin. With a rakish mustache, permanent bed head, and a purple, fur-trimmed jacket, he could be a hipster in any provincial Chinese city. He has a middle school education, and when the barge pulled up at a lock, it was Little Zhu who stepped ashore to deal with officialdom. (Although Old Zhu is only 46, he’s illiterate.) Off duty, Little Zhu seemed to spend most of his time texting his girlfriend, who worked in a bakery back in Jining. He plans to bring her aboard to live in his room in the bow after they are married. “It will be hard for her because she isn’t a chuanmin,” Huang said. “But she’s a good girl. She works hard.”

“Chuanmin rarely indulge themselves. They live by the hard-nosed calculations that determine whether a family gets rich or is ruined. This was driven home to me at the end of our first day. I was chatting with Zheng Chengfang, who came from the same village as Old Zhu. Our boats were tied up together, and I’d hopped over to visit with him. Wasn’t it a wonderful sight, I said to Zheng as we surveyed Old Zhu’s boat, freshly painted and gleaming in the sunset? “No, no, no, you don’t understand us,” he blurted out. “It’s not a question of good. We chuanmin need the boats, or we can’t survive.”

“Zheng accompanied me back to our barge for a smoke with Old Zhu, while Huang cooked a simple dinner of salted fish, rice, and stir-fried greens. “If you’re going to write about us, you also need to know something else,” Zheng said. “We chuanmin are at the receiving end. The coal owners set the price, the moneylenders set the interest, and the government officials set the fees. All we can do is nod and continue working.”

“This is a common refrain among barge owners: Like peasants working the fields, they have little control over their fate. In the countryside it’s the vicissitudes of weather, but chuanmin face whimsical bureaucrats and unpredictable economics. They must make complicated decisions based on everything from the direction of world commodity prices to Chinese banking reforms. Indeed, while Zheng was holding forth, Old Zhu was fixated on the TV news about the Middle East and the price of oil. “What do you think?” he asked me, cutting Zheng off. “Will oil top a hundred dollars a barrel? And what about steel?”

Traveling on the Grand Canal

Ian Johnson wrote in National Geographic:“Halfway into our two-week journey, we approached Yangzhou, chugging past willows dry-brushed with green and fields smudged with purple, red, and yellow flowers. “With flowers thick as mist, you head down to Yangzhou,” Li Po, an eighth-century poet, wrote. For hours I sat with Old Zhu in the pilothouse, watching the bucolic sights give way to new highway bridges being laid atop concrete pylons. [Source: Ian Johnson, National Geographic, May, 2013]

“As we cruised around one bend, Old Zhu called me out of my reverie. “That’s the old Grand Canal, or what’s left of it,” he said, pointing to a channel about 15 feet wide curving between a small island and the bank. The Grand Canal once ran in a series of winding curves, and boats had to tack east and west as they headed north and south. When it was widened and straightened, these bends either became side channels or cutoff lakes. “It was tough, let me tell you,” Old Zhu said, his raspy voice animated. “Boats coming in every direction, and you had to pay attention all the time.” His is the last generation of chuanmin who knew the old canal, with its whirlpools and eddies that could propel a barge—or ground it on a sandbar. The real miracle of the canal, it seemed to me, wasn’t the structure itself but the chuanmin, whose relationship to the waterway transcends all the changes.

“That night we docked on the outskirts of Yangzhou, the Shanghai of its day during two golden eras—the Tang dynasty and early Qing dynasty. Today in the booming south, local governments, awash in money, aim to bolster tourism and real estate development by beautifying and cashing in on the canal. But beautification can also destroy: Although Yangzhou has turned its waterfront into a park of manicured lawns and concrete pagodas—pleasant green space in an otherwise crowded city—the makeover required leveling nearly every canal-side building. For centuries the Grand Canal had been the heart of the city; now it’s just a backdrop.

“Farther south in cities such as Zhenjiang, Wuxi, and Hangzhou, the situation is worse. The canal still runs through Hangzhou’s industrial center, but with the exception of the elegantly arched Gongchen Bridge, every structure linked to it—every ancient dock, warehouse, and mooring point—has been razed. “Traditionally we talk about 18 main cities on the Grand Canal, and each had its special flair,” Zhou Xinhua, then vice director of a Grand Canal museum in Hangzhou, told me. “But now they’re all the same: a thousand people with one face.” In 2005 a small group of prominent citizens called for the historic Grand Canal to be made a UNESCO World Heritage site. “Every generation wants the next generation to understand it, to look at its monuments,” Zhu Bingren, a sculptor who cowrote the proposal, told me in an interview. “But if we wipe out the previous generations’ work, what will following generations think of us?”

“At dawn on day eight we turned east and joined the Yangtze. Now we were dwarfed by towering oceangoing ships, whose wakes swamped our decks. “The Yangtze is like a highway, and we are like a small car, so we have to go carefully and get off as quickly as possible,” Old Zhu said. Within three days we had reached our destination: the Nantong Fertilizer Plant. Because of heavy rains, it took four days to unload the barge, the hull rising imperceptibly as the crane clawed out the coal. Old Zhu then hightailed it back along the Yangtze to the canal.

“After a night moored in a cove near Yangzhou, everyone was up at dawn to get the barge moving. Rubbing the sleep from his eyes, Little Zhu untied the thick bow ropes. Old Zhu started an electric winch that pulled up the anchor. Huang cast off from the stern and stood watch. A light current carried us away from the willow-lined shore, pushing the stern out into the canal. Old Zhu walked from the winch to the pilothouse, calmly lighting a cigarette as we glided the wrong way. He pushed the starter, and the twin diesels rumbled to life.

“Barely looking back, he reversed the boat into the main channel, an act of bravura that said, This is my canal as much as anyone’s. He turned the bow upstream as other barges bore down. Then, after a dramatic pause, Old Zhu pushed the throttle full ahead. The engines surged, the propellers bit, and Lu-Jining-Huo 3307, green and shining in the soft spring light, joined the endless flow of traffic on the Grand Canal.

Shipping Accidents in China

In May 2007, sixteen crew members from Myanmar, South Korea and Indonesia drowned after a 3,800-ton South Korean cargo ship sank after colliding with a 4,800-ton Chinese freighter in heavy fog in waters off northeast China. Two life rafts were found but no one was on board. No one on the Chinese ship was hurt.

In November 2007, a cargo ship with an all-Chinese crew sideswiped the Oakland-San Francisco Bay Bridge, releasing about 200,000 liters of oil into San Francisco Bay. It was the worst oil spill in the bay in nearly two decades. A preliminary report indicated that human error rather than mechanical failure was behind the accident. The same month 11 fishermen died after their boat collided with a cargo ship off the coast of Zhejiang Province in China.

In September 2021, a boat capsized on a river in Guizhou Province in southwest China leaving at least 10 people dead, with another five still missing. CCTV said that the ship overturned shortly after it departed Saturday evening in. Preliminary investigations suggest that the ship was blown over by strong winds. Local authorities said the ship was overloaded when the accident happened. At least 46 people were on board, exceeding the maximum capacity of 40 people, according to CCTV. Rescuers had saved 31 passengers with most of the those on the boat thought to be students. Over a dozen rescue teams were dispatched to join the search and rescue operation, according to the official Xinhua News Agency. The broadcaster added that rescue boats, frogmen and divers were deployed to search for the missing, but heavy downpours and undercurrents have hampered overnight rescue efforts. [Source: Associated Press, September 19, 2021]

In December 2020, three people were killed and five sailors were missing after a collision between two ships at the mouth of the Yangtze River that. CCTV showed dramatic footage of crews pulling 11 of the 16 sailors who had been on board the container vessel Xinqisheng 69 from the water, three of whom showed no signs of life. The Yangtze is China’s most heavily trafficked river and the point at which it meets the East China Sea, just north of the commercial hub of Shanghai, brings together ships from all directions. State media reported the container ship Oceana lost power shortly before midnight, after which the Xinqisheng 69 collided with it, capsized and sank. It had been carrying 650 cargo containers, according to the China Daily. [Source: Associated Press, December 14, 2020]

Ferry and Boat Accidents in China

In November 1999, a ferry with 312 people on board caught fire and capsized during a storm in icy waters about 1.5 miles off the eastern port of Yantai in Shandong province. A total of 276 people died. Many people froze to death in their lifeboats. A distress signal was sent out at 4:30pm but no help arrived until the following morning. A few people made it to shore in lifeboats or by swimming. One survivor told AFP, "All the passengers rushed up into the upper deck around 4:00pm when we saw a lot of smoke coming from the lower decks. The winds were so strong I cannot describe it...I decided to jump into the water because the smoke was so strong it was hard to breath." He swam to the shore.

Boat collisions are common on the Yangtze River. In May 2003, a collision between a ferry and a freighter occurred in heavy fog near Peilinglun, 270 miles from Yichang, left 90 people dead or missing. Both vessels had violated regulations that prohibit them from leaving port in heavy fog.

In April 2007, 20 crew members were missing after a 17,610-ton Chinese vessel collided with a 6,500-ton Cambodian vessel. In June 2007, 23 people were injured in Shanghai when a tourist boat carry 216 people collided with a small cargo ship in the Huangpu River. At least one tourist, a Japanese, received treatment at a hospital for multiple fractures.

Hundreds Killed When a Yangtze Tourist Ship Sinks

Hundreds were killed, including many elderly tourists, when tourist ship carrying 458 people capsized in the Yangtze River. Shortly after the disaster occurred AFP reported: “Just 14 people have been confirmed as surviving after the Dongfangzhixing, or "Eastern Star," a tourist boat rapidly overturned. Six bodies have been recovered from the wreckage, leaving hundreds more still missing, possibly trapped within the ship which apparently sank in a matter of seconds. Local reports said the passengers were mostly aged over 60. Television footage showed rescuers on top of a section of the ship's hull which remained above water, some pressing their ears against it. [Source: Neil Connor, AFP, June 2, 2015]

“Zhang Hui, a 43-year-old tour guide on board, described a storm roiling the boat which tilted by as much as 45 degrees just after 9:00 pm local time, Xinhua said. "Rain poured down on the right side of the boat, many rooms were flooded," Zhang said, according to Xinhua. "Even if the windows were shut, water leaked through." Passengers began taking soaked quilts and TV sets into the ship's hall around 9:20 pm (1320 GMT), Xinhua quoted Zhang as saying, in what appeared to be an attempt to keep the items dry. Passengers seemed to have little warning before the ship sank minutes later with Zhang recalling he had "30 seconds to grab a life jacket".

“The captain and chief engineer, who were among the few survivors and being questioned by police, both reportedly said it had been caught in a freak "cyclone". As heavy rains continued to hit the area, an AFP photographer saw more than a dozen ambulances driving away from the rescue area, and at least two body bags apparently containing dead passengers. “Teams of police worked to get small motorboats in the water to search for survivors in the rain, while other emergency personnel looked on from the shore.

“The accident occurred in the middle reaches of the Yangtze, a wide and rapidly flowing waterway. CCTV said the 250-feet (76.5-meter) long vessel had floated three kilometers (1.9 miles) down river after it capsized in Jianli county, part of the central province of Hubei. Xinhua reported that three divers found one 21-year-old man in a small compartment Tuesday afternoon, saying he was given diving apparatus and able to swim out by himself. State broadcaster CCTV showed rescue workers carrying an elderly woman on a stretcher, adding that another 65-year-old woman was in "good physical condition," after being hauled from the boat.

“The vessel was owned by a firm that operates tours in the scenic Three Gorges dam region, some distance from the accident site. The boat sent no emergency signal and seven people from the boat swam to shore to raise the alarm after it sank, according to reports. The ship started operations in 1993 and was due to be retired in three years, the 21st Century Business Herald quoted an unnamed former senior executive with the Chongqing Eastern Ship Company as saying. Chinese President Xi Jinping earlier ordered "all-out rescue efforts" to find any survivors. The Hubei Daily said about 150 boats — including about 100 fishing vessels — and more than 3,000 people were involved in the rescue effort, including 140 divers. Distraught relatives of the passengers gathered at a Shanghai travel agency on Tuesday, sobbing and pleading for information on their loved ones' fate.

According to the New York Times: “ The Beijing News, a relatively liberal daily in the Chinese capital, raised a series of questions, including whether there should have been more advance notice of the storm, whether the ship was too old or overloaded, why it took more than an hour to alert the authorities after the ship sank, and how the captain managed to survive when so many others did not. Alternative sources of information and discussion on Chinese social media have been extremely limited, in part because of continuing clampdowns on freewheeling discussions online, Mr. Xiao said. The phrases “Oriental Star” and “shipwreck” were the most censored search terms on the Sina Weibo microblog platform, according to the monitoring site freeweibo.com. “It’s amazing not only how little information there is but how little discussion there is, other than general expressions of anxiety,” Mr. Xiao said. “There’s nothing people can do. There’s no independent information to see what’s going on.” [Source: Edward Wong and Austin Ramzy, New York Times, June 3, 2015]

The Oriental Star was one of six vessels that were detained in 2013 for unspecified violations as part of an effort to improve the safety of ships on the Yangtze River, according to a document posted online from the Nanjing Maritime Safety Administration. Some evidence emerged suggesting that the captain, Zhang Shuwen, might have taken the vessel into harm’s way even as other ships took precautions against the storm. The local weather bureau had issued a “yellow warning,” and at least two other ships in the vicinity appear to have stopped because of the weather, according to government satellite data and interviews with passengers.

Image Sources: 1) Columbia University; 2) BBC, Environmental News; 3, 7) University of Washington; 4, 5, 6) Nolls China website ; Julie Chao, Wiki Commons ; YouTube

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated July 2022