HISTORY OF EDUCATION IN CHINA

model student A strong education system has long been important in Chinese culture and remains so with the Chinese Communist government. The Han Chinese invented an original system of writing more than 3,000 years ago, and the university more than 2,000 years ago.Both traditional Confucians and the Communist Party view education as a method for inculcating values in the young. The educator John Dewey traveled to China in 1919, where his ideas about the “student-centered” education were all the rage there.

Ting Ni wrote in the World Education Encyclopedia: Since the founding of the People's Republic of China in 1949, education has been valued for the improvement of Chinese society rather than as a basic human right. Although the fundamental purpose or function of education has not changed, there have been some structural changes. Qualified personnel have been trained, and school conditions have improved. Education reform has progressed steadily—the nine-year compulsory education program has been implemented, primary education is becoming universal, and technical and vocational education has developed. Higher education also has developed quickly. Enrollments have increased, and a comprehensive system featuring a variety of disciplines is in place. Education for adults and minorities has been funded, and international exchange and studying abroad opportunities are also available. Most types of educational reforms in China since the 1980s have led to decentralization and the granting of semi-autonomy to lower administrative levels. In addition, college education has become a prerequisite for official bureaucratic positions. [Source: Ting Ni, World Education Encyclopedia, Gale Group Inc., 2001]

“However, much remains to be done in order to provide education to most Chinese citizens. Overall, education is insufficiently and unevenly developed. The discrepancy in the quality of education between rural areas and urban areas is overwhelming. There are no reliable sources of rural school financing. Investment in education also is inadequate. Teachers' salaries and benefits remain low, and working conditions often are poor. The elitist nature of key schools and the early determination of students' majors prevent students from discovering and developing their talents and imagination freely. The "brain-drain" problem goes beyond accommodating returned students from the West. Educational philosophy, teaching concepts, and methodologies are divorced from reality to varying degrees; practical and personal applications need to be emphasized over ideological and political work in the curriculum. Furthermore, the educational system and its management mechanism cannot meet the needs of the continual restructuring of the economy, politics, science, and technology. These problems are caused by variable combinations of politics, economics, and professional assumptions about how to develop modern education in China. As the economy expands and the reform deepens, serious efforts must be made to solve these educational problems.

See Separate Articles: EDUCATION IN CHINA: STATISTICS, LITERACY, WOMEN AND TEST SCORE SUCCESSES Factsanddetails.com/China ; TRADITIONAL VIEWS ON EDUCATION IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; VILLAGE EDUCATION AND SCHOLARS IN 19TH CENTURY CHINA factsanddetails.com ; CHINESE EDUCATION SYSTEM: LAWS, REFORMS, COSTS factsanddetails.com ; CHINESE SCHOOLS Factsanddetails.com/China ; SCHOOL CURRICULUM IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ;

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: : Education: “ “Education for Life” (China Academic Library) by Xingzhi Tao Amazon.com; “Education in China: Philosophy, Politics and Culture” by Janette Ryan Amazon.com; “Educational System in China” by Ming Yang (2009) Amazon.com; In the Past: “Confucian Philosophy for Contemporary Education” (Routledge International Studies in the Philosophy of Education) by Charlene Tan Amazon.com; “Neo-Confucian Education: The Formative Stage” by Wm. Theodore de Bary and John W. Chaffee Amazon.com; “Education and Society in Late Imperial China, 1600-1900" by Benjamin A. Elman and Alexander Woodside Amazon.com; “The Education of Girls in China” by Lewis Ida Belle (1887- 1969) Amazon.com; “The Chinese System of Public Education” by Ping Wen Kuo (1915) Amazon.com; Mao Era: “Radicalism and Education Reform in 20th-Century China: The Search for an Ideal Development Model” by Suzanne Pepper Amazon.com; “The Chinese System of Public Education (Columbia Univ Teachers College) by Ping-Wen Kuo (1972) Amazon.com;“My Family: a Normal Intellectual Family Suffered under the Rule of the Communist Party of China” by Luowen Yu Amazon.com; After Mao Era: “Social Changes and Yuwen Education in Post-Mao China by Min Tao Amazon.com; “In Search of Red Buddha: Higher Education in China After Mao Zedong, 1985-1990" by Nancy Lynch Street Amazon.com

Early History of Education in China

Ting Ni wrote in the World Education Encyclopedia: By 2000 B.C., Chinese education had developed to the level of institutions specifically established for the purpose of learning. From 800 to 400 B.C. China had both guoxue (government schools) and xiangxue (local schools). Education in traditional China was dominated by the keju (civil service examination system), which began developing around 400 A.D. and reached its height during the Tang Dynasty (618-896). Essentially, the keju was a search program based on the Confucian notion of meritocracy. This civil service examination system remained almost the exclusive avenue to government positions for China's educated elite for more than 1,000 years.[Source: Ting Ni, World Education Encyclopedia, Gale Group Inc., 2001]

“Historically, formal education was a privilege of the rich. Mastering classical Chinese, which consisted of different written and spoken versions and lacked an alphabet, required time and resources most Chinese could not afford. As a result, for much of its history, China had an extremely high rate of illiteracy (80 percent). The result was a nation of mass illiteracy dominated by a bureaucratic elite highly educated in the Confucian classical tradition. The earliest modern government schools were created to provide education in subjects of Western strength such as the sciences, engineering, and military development to address Western incursion and to maintain the integrity of China's own culture and polity. The aim of these schools was to modernize technologically by imitating the West, while maintaining all traditional aspects of Chinese culture. These schools were never integrated into the civil service examination system.

See Separate Articles CHINESE LITERATI AND SCHOLAR-ARTIST-POETS factsanddetails.com ; CHINESE IMPERIAL EXAMS factsanddetails.com CHINESE SCHOLAR-OFFICIALS AND THE IMPERIAL CHINESE BUREAUCRACY factsanddetails.com ; CONFUCIANISM, GOVERNMENT AND EDUCATION factsanddetails.com

Classical Chinese Education

Arthur Henderson Smith wrote in “Chinese Characteristics”: “The whole system of Chinese education is directed to the object of making the pupils remember the words of the classics. This is a prerequisite for the use which he is eventually to make of them. Therefore in the early years, when the memory is vigorous, it is loaded down with the most incongruous and fatal burden of matter not one thousandth of which is or can be comprehended by the pupil. If he perseveres in his course, the time will eventually arrive when this mass of inert matter will be more or less perfectly digested. Explanations will be given and received, and intellectual daylight will dawn. [Source:“Chinese Characteristics” by Arthur Henderson Smith, 1894]

“But to the vast mass of pupils, whose term of study is limited to a few years, no such result will follow. They are the victims of "intellectual infanticide" on a gigantic scale. They have learned to repeat but not to think; and memory of what they learned to repeat grows fainter year by year and soon totally disappears, leaving a more or less complete mental vacuity. When we speak of China as ruled by its men of learning, we must take account of the uncounted millions of minds that have been partially or wholly blighted by this terrible system. Its constant inevitable tendency is to cultivate a profound reverence for the form, at the expense of that for which the form should stand. Multitudes who can recognize characters with comparative readiness, when an unfamiliar book is submitted to them are found to be occupied solely with the correct enunciation of the ideographs, to the utter exclusion of any thought as to the ideas which the characters are intended to convey. Chinese education produces some remarkable results, but it produces them at an expense of intellectual waste which might make angels weep.

Education in Qing Dynasty China

Arthur Henderson Smith said that “all the examination halls, from the lowest to the highest, seem to be perpetually crowded”, but also described the “intellectual turbidity ” of China and said“education in China is restricted to a very narrow circle”. Anatoly Karlin wrote: These observations are confirmed by the historical fact that primary enrollment was at just 4 percent of the eligible school-age population in China in 1900. Common folks come off as pretty stupid, and unable to grasp the essence of the questions put to them. For instance, in reply to a query about his age, one man’s answer is said to resemble a “rusty old smoothbore cannon mounted on a decrepit carriage.”[Source:Anatoly Karlin, March 28, 2013. Karlin is a blogger, thinker, and businessman in the San Francisco area. He is originally from Russia, spent many years in Britain, and studied at U.C. Berkeley ~|~]

Arthur Henderson Smith wrote in “Chinese Characteristics” in 1894:“The Chinese are unfortunately deficient in the education which comes from a more or less intimate acquaintance with chemical formulae, where the minutest precision is fatally necessary. The first generation of Chinese chemists will probably lose many of its number, as a result of the process of mixing a “few tens of grains" of something, with "several tens of grains" of something else, the consequence being an unanticipated earthquake. The Chinese are as capable of learning minute accuracy in all things, as any nation ever was — nay more so, for they are endowed with infinite patience — but what we have to remark of this people is, that as at present constituted, they are free from the quality of accuracy, and they do not understand what it is. If this is a true statement of a "true fact," two inferences would seem to be legitimate. [Source:“Chinese Characteristics” by Arthur Henderson Smith, 1894. Smith (1845 -1932) was an American missionary who spent 54 years in China. In the 1920s, “Chinese Characteristics” was still the most widely read book on China among foreign residents there. He spent much of his time in Pangzhuang, a village in Shandong.]

“A Chinese education by no means fits its possessors to grasp a subject in a comprehensive and practical manner. It is popularly supposed in Western lands that there are certain preachers, of whom it can be truthfully affirmed that if their text had the small-pox, the sermon would not catch it. The same phenomenon is found among the Chinese, in forms of peculiar flagrance.

Chinese dogs do not as a rule take kindly to the pursuit of wolves, and when a dog is seen running after a wolf, it is not unlikely that the dog and the wolf will be moving, if not in opposite directions, as least at right angles to one another. Not without resemblance to this oblique chase, s the pursuit of a Chinese speaker of a perpetually retreating subject. He scents it often, and now and then he seems to be on the point of overtaking it, but he retires at length, much wearied, without have come across it in any part of his course.

“The system of parasitism is a constituent part of the educational routine of the Chinese. The relation between teacher and pupil is far more intimate than any with which we are acquainted, and a person who has once been a preceptor of another, has a kind of presumptive claim upon him as long as he lives. When the teacher is poor and in distress, as happens to a large percentage of Chinese teachers, he may get his entire living by roaming aboutand levying small contributions on his former pupils. If this is insufficient, as it is not unlikely to be, a poor teacher becomes a " Roving Scholar," like/some of the monks in the Middle Ages, and reepixes a trifle in alms at every school-house at which he * stops, itfi circumstance that two persons have studied together under the" same teacher, or have been examined at the same time for a degree, constitutes a claim upon which aid in distress is continually based. " Indeed to such a pitch of perfection -is parasitism carried, that there are everywhere clever vagrants roaming about picking up acquaintances, insinuating themselves into the affairs of others, learning where their relatives live, and who they are, in order to hunt up such of them as seem to be worth the trouble, and by representing themselves as friends of their friends, gain a little advantage in the shape of a meal or a lodging, or both.

Qing Dynasty Education Reforms

Ting Ni wrote in the World Education Encyclopedia: “In 1898, Emperor Guang Xu, supported by Kang Youwei and Liang Qichao, well-known reformers, issued a series of decrees to initiate sweeping reforms in Chinese education. The measures included the establishment of a system of modern schools accessible to a greater majority of the population, abolition of the rigid examination system for the selection of government officials, and the introduction of short and practical essay examinations. [Source: Ting Ni, World Education Encyclopedia, Gale Group Inc., 2001]

“Between 1901 and 1905, the Qing court issued a new series of education reform decrees. The old academies that had supported the civil service examinations were reorganized. A modern school system was built on their foundations with primary, secondary, and college levels reflective of Western models. Schools throughout China were organized into three major stages and seven levels. Elementary education was composed of kindergarten, lower elementary, and higher elementary; secondary education consisted of middle school; and higher education was divided into preparatory school, specialized college, and university. The Qing Court also instructed provincial, prefectural, and county governments to open new schools and start a compulsory education program. The civil examination system (keju ) was officially abolished in 1905, marking the end of the trademark of traditional Chinese education.

“Six years later, China's dynastic tradition also came to an end when the new Nationalist Republic replaced it. With this political metamorphosis, China's educational system experienced further transformations.

Education in Republic China

The Republic of China refers to the historical period that followed the collapse of the Qing Dynasty in 1912, the rise of the Kuomintang (KMT) government, and finally the Communist reunification of China in 1949. Ting Ni wrote in the World Education Encyclopedia: The search for modern nationhood and economic prosperity created the first golden age of education in modern China. Education in China enjoyed a rare interval of uninterrupted growth as the Beijing government enthusiastically pursued educational development in both the public and private sectors as an essential component of the Nationalists' nation-building program. In 1912 and 1913 the Republican government issued Regulations Concerning Public and Private Schools and Regulations Concerning Private Universities; these documents laid out the criteria for private schools and stipulated proper application and registration procedures, while calling for financial investment in education nationwide. [Source: Ting Ni, World Education Encyclopedia, Gale Group Inc., 2001]

“The eruption of the Sino-Japanese War in 1937 and rapid Japanese conquest of coastal areas in the months immediately following changed the educational situation dramatically. As a result of military operations, 70 percent of Chinese cultural institutions were destroyed. By November 1, 1937, no less than 24 institutions of higher learning had been bombed or demolished by the Japanese. Seventy-seven of China's institutions of higher learning were either closed down or literally uprooted and moved many hundreds of miles into the interior. Not all the students could follow their respective universities. As a result, the retaining rate of their original student bodies for these institutions ranged from 25 to 75 percent. The subsequent civil war (1946-1949) between the Nationalists and the Communists continued to subject China to a state of political turmoil in which education suffered drastically as a result.

Photographs help flesh out the period somewhat. Based on these Feng Keli wrote in Sixth Tone: “A photograph, taken in 1936, depicts residents of Zhenjiang, a city in eastern China’s Jiangsu province, standing before the window of a Popular Education Center — a government-sponsored mass teaching initiative. A young woman wearing a floral qipao dress and two small girls in her care have paused to look at a poster; the woman appears to be explaining something to the children. The slogan written in traditional Chinese characters across the window display reads: “Raising and caring for children is the responsibility of both parents and teachers.” [Source: Feng Keli, Sixth Tone, May 3, 2018; translator: Owen Churchill; editors: Zhang Bo and Matthew Walsh]

“The taller girl standing on the left is called Huang Yongmei. In 1999, when she was 70 years old, she contributed this image to “Old Photos” and published a memoir with us. “It was the autumn of 1936,” Huang recalled. “I was 7 years old and a pupil in second grade at the [Popular Education Center] primary school. My father died when I was 4, after contracting an acute illness while he was teaching out of town. My mother watched over me and my younger sisters at our family home in Zhenjiang, where we depended on each other for everything.” Huang’s school was located in a Confucian temple less than 100 meters from her home. “The young, modern principal, Mrs. Wang, was the wife of a man who studied abroad,” Huang explained, although she didn’t remember where he had studied. “She would stand at the lectern and demonstrate how to brush our teeth, or tell us about how Japanese militarists were brainwashing Japanese children with ideas about invading China.”

The Popular Education Center instructed children in both Chinese and Western educational principles, passing on both traditional Chinese culture and knowledge considered more “modern” — for example, personal hygiene...In the temple’s main hall were displayed a collection of small clay figurines of characters from classic tales in the Chinese canon. “There were also models and pictures used for education about personal hygiene,” Huang continued. “Most fun of all, the education center would screen movies on weekends for local residents. Being able to watch [Charlie] Chaplin’s slapstick performances back then — silent though they were — was hugely enjoyable.”

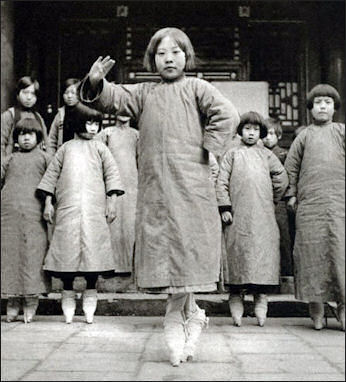

“Rural schools, too, were encouraged to embrace new educational strategies.” A group of photograph s “captured in January 1937 in Wenshui — a county in northern China’s Shanxi province — shows both staff and students at a girls’ primary school in Li Village. “The woman sitting upright in the center of the shot is probably the school principal. Her smart clothing and confident aura make me think that she probably received a “modern” education, a privilege that would have been denied to most women at the time. Similarly, all the female students in the photograph are smartly dressed and proper-looking. A traditional Chinese saying exhorts us to leave the best buildings for educators and students, and the carved beams and painted rafters behind this group indicate that local villagers took that to heart.

“The presence of the female headteacher is made more arresting by the four men at her side. Due to the patriarchal nature of Chinese society, senior men tend to pose front-and-center in most old photographs, while women are usually relegated to the background. This image goes against that custom and hints at early visual representations of female emancipation. That’s one reason why I like this shot so much: Often, social progress is revealed not through the bedlam of concerted political campaigns, but through the gradual changes seen in life’s inconsequential details.

Foreign Influence on Chinese Education

Ting Ni wrote in the World Education Encyclopedia:“Foreign influences on Chinese education manifested themselves through two main channels: foreign missionary schools and the Western-educated Chinese. Missionary education in China dates back to 1818 when British missionaries opened schools in Malacca for the children of overseas Chinese. Starting in the 1840s, missionary schools came under the protection of a series of "unequal treaties" between the Chinese government and the Western powers. The second half of the nineteenth century witnessed a steady rise in the number of mission schools due to missionaries' growing interests in education and a general advancement of Western powers in China. In many ways, mission schools were a catalyst for the educational reform in modern China. [Source: Ting Ni, World Education Encyclopedia, Gale Group Inc., 2001]

“The reform was initiated in the 1860s as a component of the Self-Strengthening Movement and sponsored by a few high-ranking officials involved in yiwu, (barbarian affairs). From the point of view of the Chinese court in Beijing, there was an urgent need to understand Western culture and Westerners. In 1903 the imperial government issued the Guidelines for Educational Affairs, which established an educational system modeled after that of the Japanese, who had successfully replicated the Western system.

“During the Nationalist decade (1928-1937), Chinese education experienced a transition from the earlier Japanese model to the American model, partly because of the return of students from the West, especially the United States, and partly because of China's deteriorating relationship with Japan. China started a public school system patterned after that of the United States and adopted American textbooks in its 1922 educational system.

“In addition to help from universities and colleges in the United States, American missionary colleges in China also played an important role in the Americanization of the Chinese educational system. By the 1930s there were 16 Christian colleges and universities in China. Three of them were sponsored by Catholic missions and 13 of them were by Protestants. Academically, they were the first to introduce relatively comprehensive programs in science, technology, and medicine. However, in spite of all their positive attributes and efforts to communicate with the Chinese populace, a huge gap always existed between mission schools and Chinese society at large. The factors that contributed to the distance included the unwillingness of the missionaries to learn Chinese and the unwillingness to address Chinese concerns about national sovereignty and China's cultural heritage.

“Missionary institutions not only transformed the life of Chinese youth who enrolled in them, but also smoothed the way for those who desired to study abroad. For students who planned to go abroad to pursue graduate studies, a degree from a western missionary school was invaluable. The pro-Western attitude manifested itself most in universities and colleges in the 1920s and 1930s. By 1927, Western-educated men monopolized nearly all important posts in higher education. Returnees, especially those from the United States, also dominated the diplomatic corps, military forces, and top government positions. After the founding of the People's Republic of China in 1949, the Communist Party expelled all missionary schools from China and forbade Chinese from going to the West to study, except for a very few who were allowed to study Western languages for diplomatic purposes. These measures were intended to end all Western influences on Chinese education. Since 1949 there has not been any private school operated exclusively by foreigners in China.

Development of Chinese Women’s Education in China

In the 1940s, Nationalist Ministry of Education bureaucrats in conjunction with educators in teacher training schools developed social education experimental zones in China’s interior. The purpose of the zones was to improve the physical and emotional quality of citizens by addressing all aspects of their daily existence. The training document from which the epigraph is taken shows the significance the ministry attached to a mother’s role in developing the attitudes and behaviours conducive to a stable social order. The female and male intellectuals who worked in these zones, including Nationalist bureaucrats, educational leaders, and students, believed that improving the quality of how women dealt with the daily fundamentals of family management was key to the nation’s long-term success and positive development. The goals of creating a stable society and saving China from national disintegration were directly and intimately related to the work of making families happier. [Excerpt: “Keeping the Nation’s House: Domestic Management and the Making of Modern China” by Helen M. Schneider, University of British Columbia Press 2011, China Beat, May 31, 2011, Helen M. Schneider is Assistant Professor of History at Virginia Tech and currently a Research Associate at Oxford University.

One of the goals was “to cultivate children’s happiness. The basic idea is that you want your child to feel satisfied. Even if the food is unsatisfactory, the clothes are inadequate, or the habitation is insufficient, you still should tell your child that it is very good. You do not want the child to be greedy and insatiable. In the future whether or not he is law-abiding, well-behaved, satisfied, or works for his own knowledge and does not simply enjoy the fruits of other’s labor, these all start from this word: “Happiness.”--

In the first half of the twentieth century, Chinese intellectuals felt that women were responsible for perfecting their management of domestic space in order to strengthen the Chinese nation. As the Qing dynasty experienced dramatic decline at the end of the nineteenth century, intellectual leaders believed that women, because they were uneducated and superstitious and had bad habits that were a negative influence on their children, were at least partly responsible for China’s weaknesses. They wanted women to be better prepared for their responsibilities as mothers and wives and, in the final years of the dynasty, Qing officials mandated that new schools for girls and teacher training schools should train women in important skills that would prepare them for their gendered responsibilities as household managers. [Excerpt: “Keeping the Nation’s House: Domestic Management and the Making of Modern China“ by Helen M. Schneider, University of British Columbia Press 2011, China Beat, May 31, 2011, Helen M. Schneider is Assistant Professor of History at Virginia Tech and currently a Research Associate at Oxford University.

In these new schools, educators taught household management classes and encouraged women to take their roles as wives and mothers seriously in order to ensure the future stability of the nation. As more schools of higher education opened up to girls, the emphasis of domestic science shifted from a curriculum in housekeeping skills to the preparation of domestic managers with scientific skills. By the end of the 1920s, the field as it was taught in normal schools and colleges no longer trained women solely for their wifely roles; instead, the discipline of home economics prepared women who might not only manage households efficiently but also manage projects of social reform and help engineer a better China. The graduates of home economics programs and their fellow intellectuals, such as the participants in the wartime social education experimental zones, created and promoted a broader agenda of nurturing an emotionally stronger, physically healthier, and more productive citizenry prepared to meet the challenges of the modern age.

The discipline of home economics facilitated the formation of a group of white-collar professional women who advocated more rational ways of living and practical habits for all Chinese people. In the government’s support for home economics and its regulation of the social education experimental zones, it is clear that one cornerstone of social order was the division of fundamental responsibilities between men and women. Educators, administrators, and officials alike clearly delineated these differences as they asked women to pay particular attention to domestic responsibilities, to matters of emotional development, to internal management, and to significant daily tasks such as cleaning, cooking, and child rearing. The discipline of home economics thus tells us much about how a system of gendered responsibilities was institutionalized and made foundational to the Chinese nation-state.

Chinese Education Under the Communists

Red Guards burn books The goal of the early Communist education policy was to teach the masses how or read and write, and channel talented young people into science and technology. It was oriented more towards meeting the needs of society and the state rather than fostering individual development. Schools were free, compulsory, universal and classless and were used disseminate Communist doctrine as well as educate children.

Under Mao, the educational system suffered from propaganda and the devaluation of intellectual pursuits. During the Cultural Revolution in the 1960s and 70s schools were closed, teachers were harassed, young people went to work in the countryside and people had to study in secret. One woman who made it into university after the Cultural Revolution told Reuters, “We would get up to jog and study so early that the stars were still in the sky. Everybody wanted to win lost time back.” See Cultural Revolution, China Under Mao, History

Mao ended the university entrance exam in 1966, saying that education system was dominated by the exploiting class. Universities resumed partial recruitment in 1970, but only workers, farmers and soldiers with revolutionary credentials that had been recommended were admitted. Some ambitious students became manual laborers so they would have a better chance of getting into university. One such student told Reuters he made into a university in part because he was “a good hand in the cotton fields at anything from sowing and weeding to spraying pesticides and harvesting.”

The Chinese education system has been touted as providing a “a fair pathway to advancement” but is often criticized for not providing enough money for primary and secondary education and for not doing more to improve the poor-quality of Chinese universities. Every school has a Communist Party secretary who outranks the principal, ensuring control over education. In the 1990s and 2000s there was an emphasis in Chinese educational policy on improving secondary, technical, and vocational education and on extending educational opportunities to remote areas and undereducated populations.

Ting Ni wrote in the World Education Encyclopedia: “After the founding of the People's Republic of China (PRC), the new Communist government pursued the movement to "learn from the Soviet Union" with all the enthusiasm that had characterized the Western imitation process in earlier decades. The entire national educational system was first reorganized to conform to the Soviet model in 1952-53. American-style liberal arts colleges were abolished, with arts and science facilities separated from the larger universities to form the core of Soviet style zonghexing (comprehensive) universities; about 12 of these were formed, in more or less even distribution around the country. The remaining disciplines of the old universities were reorganized into separate technical colleges or merged with existing specialized institutes. Also following the Soviet example, nationally unified teaching plans, syllabi, materials, and textbooks were introduced for every academic specialty or major. [Source: Ting Ni, World Education Encyclopedia, Gale Group Inc., 2001]

“The Great Leap Forward of 1958 introduced educational reforms as part of a comprehensive new strategy of mass mobilization for economic development. To end the continuing influence of such pre-revolutionary ideas as "education can only be led by experts" and "the separation of mental and manual labor," as well as to strengthen party leadership, the Ministry of Education (MOE) issued a directive on September 19, 1958, launching the educational reforms. It called universities to fill both academic and administrative leadership positions with party members. Productive labor became part of the curriculum in all schools at all levels. More specifically, the half-work/half-study schools were founded to meet the task of rapidly universalizing education for the masses, since these schools could be run on a self-supporting basis without financial aid from the state. The party directives also stipulated that no professional educational staff was necessary; anyone who could teach would suffice.

Early Communist Boarding Schools

Didi Kirsten Tatlow of the New York Times wrote: “Millions of Chinese who attended boarding nurseries and preschools after the Communist revolution in 1949, when large-scale systems of institutional care were established to free parents to pursue revolution or to labor, experienced John’s plight to some degree. The generation most deeply affected may be those born in the early decades after 1949, as the boarding system spread unquestioned — those in their 50s and 60s who run the country today.” Many Chinese who attended such schools have “stories of losing primary caregivers, or of being forced to separate from their own children because of rules barring parents from staying with their hospitalized children. [Source: Didi Kirsten Tatlow, Sinosphere, New York Times, October 5, 2016]

“Boarding school is less common now for those under 6 but is still considered a respectable option. Even Chinese millennials may have been sent as toddlers. It is widespread among children 6 and older. Documents at the Beijing municipal archives show that, at top institutions in the city after the revolution, the caregiver-to-child ratios were initially high. Mostly, the children of the elite were sent away. The children of ordinary citizens were cared for at home.

“A 1958 State Council document recorded a 1-to-2 ratio in 1956 at a nursery run by the Ministry of Agriculture. But colder times began with the 1958 “double-anti” campaign against “waste and conservatism.” Spending on food and board was cut everywhere, the document showed. The caregiver ratio at the ministry nursery went to 1-to-5.5 that year. The authorities promised to get it to 1-to-5.9, in line with “rectification.” Conditions in less privileged preschools grew grim as the authorities pushed to institutionalize large numbers of children to free parents to meet higher production quotas during the Great Leap Forward of 1958 to 1961.

“Another document, dated 1960, noted: “The problem now is that the development of boarding nurseries isn’t keeping up with the development of the needs of production.” Facilities were built quickly but were “small and cramped.” Only 26 percent were “good.” In Beijing, 400,000 children needed preschool places immediately, the document said. With the able-bodied working in fields or factories, the caregivers were often old or sick. At one preschool, the document said, six children drowned in one summer and three got food poisoning, with one dying.

“Conditions have improved drastically since then, but loyalty to the system remains. An article published one week before school began on Sept. 1, by Shilehui, a website for preschool educators, addressed the issue. Hardly any parent likes to send a young child to be boarded, it said. But in the interests of “objectivity,” it listed three advantages: Boarding helps children become more independent and less finicky and make more friends.

Education and the Cultural Revolution

There have traditionally been tensions within the education system, which served, as it does in most societies, to sort children and select those who would go on to managerial and professional jobs. It was for this reason that the Cultural Revolution focused so negatively on the education system. Because of the rising competition in the schools and for the jobs to which schooling could lead, it became increasingly evident that those who did best in school were the children of the "bourgeoisie" and urban professional groups rather than the children of workers and peasants. The Maoist policies on education and job assignment were successful in preventing a great many urban "bourgeois" parents from passing their favored social status on to their children. This reform, however, came at great cost to the economy and to the prestige and authority of the party itself. [Source: Library of Congress]

“China’s education system was destroyed by the Cultural Revolution. Cultural Revolution-era policies led to the public deprecation of schooling and expertise, including closing of all schools for a year or more and of universities for nearly a decade, exaltation of on-the-job training and of political motivation over expertise, and preferential treatment for workers and peasant youth. Educated urban youth, most of whom came from "bourgeois" families, were persuaded or coerced to settle in the countryside, often in remote frontier districts. Because there were no jobs in the cities, the party expected urban youth to apply their education in the countryside as primary school teachers, production team accountants, or barefoot doctors; many did manual labor. The policy was intensely unpopular, not only with urban parents and youth but also with peasants and was dropped soon after the fall of the Gang of Four in late 1976.

“Mao led vicious attacks against intellectuals, who were vilified as the “stinking ninth category.” As a result of the Cultural Revolution a rising generation of college and graduate students, academicians and technicians, professionals and teachers was lost. The result was a lack of trained talent to meet the needs of society, an irrationally structured higher education system unequal to the needs of the economic and technological boom, and an uneven development in secondary technical and vocational education.

Education Reforms After Mao

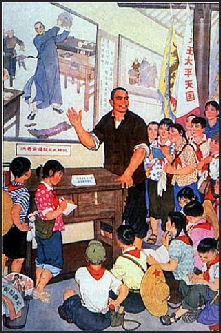

Mao-era poster

According to the Worldmark Encyclopedia of Nations:“Education was reoriented in 1978 under the Four Modernizations policy, which restored the pre-1966 emphasis on competitive examinations and the development of special schools for the most promising students. The most striking changes were effected at the junior and senior high school levels, in which students were again streamed, according to ability, into an estimated 5,000 high-quality, well-equipped schools, or into lower-quality high schools, or into the technical and vocational schools, which were perceived as the least prestigious. In addition, 96 universities, 200 technical schools, and 7,000 primary schools were designated as "key" institutions. Universities were reopened, with a renewed emphasis given to science and technology. [Source: Worldmark Encyclopedia of Nations, Thomson Gale, 2007]

Ting Ni wrote in the World Education Encyclopedia: “ After the death of Mao Zedong, Deng Xiaoping's reform period began with a major national education conference in April 1978, which abandoned the Cultural Revolution's goals of class struggle and adopted modernization as the main goal for educational development. The nation witnessed a remarkable new era of rapid reconstruction and expansion of all levels of education, especially higher education. In both the formal and nonformal sectors, one of the goals of the reforms was that a college-level education was to be a prerequisite for all officials, including county-level leaders. This is a goal yet to be accomplished in the twenty-first century, but it is already underway in the political reintegration of China's intellectuals within the ruling class. [Source: Ting Ni, World Education Encyclopedia, Gale Group Inc., 2001]

The education system was expanded under Deng Xiaoping with the understanding that an educated population was needed to make the economy grow and for China to prosper. The process was slowed by Tiananmen Square in 1989 but relatively quickly regained momentum again. The Decision on the Reform of Education System issued in 1985 aimed to change the Soviet-style, highly-specialized universities into more comprehensive institutions. The Compulsory education law if 1986 mandated nine years of compulsory education for all Chinese.

In the post-Mao period, China's education policy continued to evolve. The pragmatist leadership, under Deng Xiaoping, recognized that to meet the goals of modernization it was necessary to develop science, technology, and intellectual resources and to raise the population's education level. Demands on education--for new technology, information science, and advanced management expertise--were levied as a result of the reform of the economic structure and the emergence of new economic forms. In particular, China needed an educated labor force to feed and provision its 1- billion-plus population. [Source: Library of Congress]

By 1980 achievement was once again accepted as the basis for admission and promotion in education. This fundamental change reflected the critical role of scientific and technical knowledge and professional skills in the Four Modernizations. Also, political activism was no longer regarded as an important measure of individual performance, and even the development of commonly approved political attitudes and political background was secondary to achievement. Education policy promoted expanded enrollments, with the long-term objective of achieving universal primary and secondary education. This policy contrasted with the previous one, which touted increased enrollments for egalitarian reasons. In 1985 the commitment to modernization was reinforced by plans for nine-year compulsory education and for providing good quality higher education.

By 1980 the percentage of students enrolled in primary schools was high, but the schools reported high dropout rates and regional enrollment gaps (most enrollees were concentrated in the cities). Only one in four counties had universal primary education. On the average, 10-percent of the students dropped out between each grade. During the 1979-83 period, the government acknowledged the "9-6-3" rule, that is, that nine of ten children began primary school, six completed it, and three graduated with good performance. This meant that only about 60 percent of primary students actually completed their five year program of study and graduated, and only about 30 percent were regarded as having primary-level competence. Statistics in the mid-1980s showed that more rural girls than boys dropped out of school. Rural parents were generally well aware that their children had limited opportunities to further their education. Some parents saw little use in having their children attend even primary school, especially after the establishment of the agricultural responsibility system. Under that system, parents preferred that their children work to increase family income--and withdrew them from school--for both long and short periods of time.

Chinese Education in the 1980s

Deng Xiaoping's far-ranging educational reform policy, which involved all levels of the education system, aimed to narrow the gap between China and other developing countries. Modernizing China was tied to modernizing education. Devolution of educational management from the central to the local level was the means chosen to improve the education system. Centralized authority was not abandoned, however, as evidenced by the creation of the State Education Commission. Academically, the goals of reform were to enhance and universalize elementary and junior middle school education; to increase the number of schools and qualified teachers; and to develop vocational and technical education. A uniform standard for curricula, textbooks, examinations, and teacher qualifications (especially at the middle-school level) was established, and considerable autonomy and variations in and among the autonomous regions, provinces, and special municipalities were allowed. Further, the system of enrollment and job assignment in higher education was changed, and excessive government control over colleges and universities was reduced. [Source: Library of Congress]

Among the notable official efforts to improve the education system were a 1984 decision to formulate major laws on education in the next several years and a 1985 plan to reform the education system. In unveiling the education reform plan in May 1985, the authorities called for nine years of compulsory education and the establishment of the State Education Commission (created the following month). Official commitment to improved education was nowhere more evident than in the substantial increase in funds for education in the Seventh Five-Year Plan (1986-90), which amounted to 72 percent more than funds allotted to education in the previous plan period (1981-85). In 1986 some 16.8 percent of the state budget was earmarked for education, compared with 10.4 percent in 1984. Since 1949, education has been a focus of controversy in China. As a result of continual intraparty realignments, official policy alternated between ideological imperatives and practical efforts to further national development. But ideology and pragmatism often have been incompatible. The Great Leap Forward (1958-60) and the Socialist Education Movement (1962-65) sought to end deeply rooted academic elitism, to narrow social and cultural gaps between workers and peasants and between urban and rural populations, and to "rectify" the tendency of scholars and intellectuals disdain manual labor. During the Cultural Revolution, universal education in the interest of fostering social equality was an overriding priority.

In 1989, there were 47,717,000 secondary school students in China (4.29 percent of the national population of 1,111,910,000), of whom 58.4 percent were male. Fully 97.8 percent of children reaching school age were sent to primary schools, and 74.6 percent of primary school graduates proceeded to secondary schools. There are six grades in each secondary school: Junior Middle 1, 2, and 3, and Senior Middle 1, 2, and 3, and the age range is normally 12 to 18. In the sample studied, the mean age was 15.53 (SD = 1.78). The features described in the profiles represent the means, modes, medians, or usual ranges, or the proportions in the sample. [Source: “1989-1990 Survey of Sexual Behavior in Modern China: A Report of the Nationwide “Sex Civilization” Survey on 20,000 Subjects in China: by M.P. Lau’, Continuum (New York) in 1997, Transcultural Psychiatric Research Review (1995, volume 32, pp. 137-156), Encyclopedia of Sexuality]

“In 1989, there were about 82,000 post-secondary students in China. A study of this group is of immense importance as they are destined to become the future leaders of the country. Intellectually well endowed and highly educated, they are still young, malleable, open minded, and sensitive to new ideas and trends. In the process of maturation as scholars, they confront the various phenomena associated with modernization and accelerating change. They interact with a “campus culture,’ which may be a cultural melting pot and a frontier of novel concepts and ideologies. Restricted by demands for sexual abstinence and expectations of monogamy, they try their best to cope with their libido and desire. Their perceptions, perspectives, beliefs, and behavior will have profound effects on the future of nation-building, participation in the world community, and global stability.

Chinese Education in the 1990s and 2000s

Ting Ni wrote in the World Education Encyclopedia: ““The scene in higher education in the PRC has changed rapidly since the 1990s. With the increasing drive to modernize China by integrating free-market forces, the government has introduced radical new reforms to privatize education. The most recent reforms include introduction of student fees, abolition of guaranteed job assignment after graduation, localization of institutions, and the development of private educational institutions. [Source: Ting Ni, World Education Encyclopedia, Gale Group Inc., 2001]

In 1986 the goal of nine years of compulsory education by 2000 was established.In the mid 2000s, the population of China had on average only 6.2 years of schooling. The Ministry of Education reported a 99 percent attendance rate for primary school and an 80 percent rate for both primary and middle schools.

By 1998, there were 628,840 primary schools with 5,794,000 teachers and 139,954,000 students. At the secondary level, there were 4,437,000 teachers and 718,883,000 students. [Source: Worldmark Encyclopedia of Nations, Thomson Gale, 2007]

The United Nations Development Programme reported that in 2003 China had 116,390 kindergartens with 613,000 teachers and 20 million students. At that time, there were 425,846 primary schools with 5.7 million teachers and 116.8 million students. General secondary education had 79,490 institutions, 4.5 million teachers, and 85.8 million students. There also were 3,065 specialized secondary schools with 199,000 teachers and 5 million students. Among these specialized institutions were 6,843 agricultural and vocational schools with 289,000 teachers and 5.2 million students and 1,551 special schools with 30,000 teachers and 365,000 students. [Source: Library of Congress, August 2006]

In 2003 China supported 1,552 institutions of higher learning (colleges and universities) and their 725,000 professors and 11 million students. While there is intense competition for admission to China’s colleges and universities among college entrants, Beijing and Qinghua universities and more than 100 other key universities are the most sought after. The literacy rate in China is 90.9 percent, based on 2002 estimates.[Source: Library of Congress, August 2006]

Image Sources: Landsberger Posters ; Columbia University University of Washington; Ohio State University, Wiki Commons, Asia Obscura

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated August 2022