CHINESE GIANT SALAMANDER

The Chinese giant salamander (Andrias davidianus) is the largest of all amphibians Part of a lineage stretching back 170 million years and found in rivers and streams, they are regarded as “living fossils”. They can weigh up to 63.5 kilograms (140 pounds). Locals call them "baby fish" because they make a noise that sounds like a crying baby during the mating season. Specimens in captivity have lived to be over 60 years old.

Chinese giant salamanders can be found in 17 provinces of China, including northeast and southeast Yunnan. Particularly large ones have been found in the Qingshui and Wuyang rivers in central Guizhou. They prefer mountain streams at an elevation of 300 to 800 meters (984 to 2625 feet). They live at an average depth of 1.07 meters (3.51 feet) in waters that are rapid and clear and where there are many cracks and holes among rocks to hide in.

Chinese giant salamanders spawn in freshwater cavities or caves that are protected by an adult male. After hatching, larvae move into the streams to which these caves and cavities are connected. They spend the rest of their lives in these streams and rivers and occasionally move into larger lakes. The waters where they live nned to be heavily oxygenated and have a large amount of bank-side vegetation. [Source: Lauren Hatch, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

What are the locals doing to preserve to these rare animals? Eating them of course. Giant salamanders are regarded as a delicacy and their flesh is considered delicious. Their habitats have been greatly reduced and they are regarded as a threatened species. However they are bred in large numbers under license for human consumption in China.

Giant Salamander Amphibiaweb amphibiaweb.org ;

See Separate Article: JAPANESE GIANT SALAMANDER: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION factsanddetails.com : ENDANGERED ANIMALS IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; REPTILES IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ;

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: “How to Make a Giant Salamander: Anatomy, Physiology and Taxonomy” by Linda Coates and Jan Steele Amazon.com; “Chinese Giant Salamanders” by Susan Schafer ( Amazon.com; “Amphibians of China” by Fei Liang Zhu Amazon.com; “Chinese Wildlife” ( Bradt Travel Wildlife Guides) by Martin Walters Amazon.com; “ “Wild China: Natural Wonders of the World's Most Enigmatic Land by Phil Chapman, George Chan, et al. Amazon.com; “Wildlife Wonders of China: A Pictorial Journey through the Lens of Conservationist Xi Zhinong” by Zhinong Xi, Rosamund Kidman Cox, et al. Amazon.com; “Rare Wild Animals” (Culture of China) by Yang Chunyan, Zhang Cizu, et al. Amazon.com

South China Giant Salamander — Largest Amphibian in the World?

Chinese Giant salamanders are not just one species but at least five, and perhaps as many as eight as well as another species in Japan. The recently described South China giant salamander may be the biggest of them all

A salamander that lived at London Zoo for 20 years in the 1920s has turned out to be a new species which could be the largest amphibian in the world. The Telegraph reported: “The animal, which was kept at the zoo and later preserved at the Natural History Museum, was thought to be a Chinese giant salamander, but tests from 17 specimens held at the museum showed it was completely a new species that was actually bigger than its cousin. The amphibian, which has been called the South China giant salamander is presumed to still live in the wild. [Source: The Telegraph, September 17, 2019]

“When it lived at London Zoo, scientists in the 1920s had abandoned proposals that it could be a new species. The same salamander has now been used to define the characteristics of the new species.The South China giant salamander can reach nearly two meters and is the largest of the 8,000 amphibian species alive today, scientists from ZSL and London’s Natural History Museum said. Analysing tissue samples from wild salamanders and the DNA specimens scientists revealed three genetic lineages. These were from different river systems and mountain ranges across China and could have diverged more than three million years ago.

Giant Chinese Salamander Characteristics

Chinese giant salamanders average one meter (3.3 feet) in length and weigh approximately 11 kilograms (24.2 pounds). Big ones from the past had a total body and tail length of 1.8 to 2.0 meters (6 to 6.6 feet) and weigh 20 to 25 kilograms (44 to 55 pounds). They are cold blooded (ectothermic, use heat from the environment and adapt their behavior to regulate body temperature). Sexual Dimorphism (differences between males and females) is present: Males and females have different shapes that is most obvious around the mating season, when the cloacal glands of adult males swell and enlarge. [Source: Lauren Hatch, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

Chinese giant salamanders have a big, flat head, on which there are many bumps. They have a large, arched mouth, but their round, lidless eyes and nostrils are very small. Like all amphibians Chinese giant salamanders have vomerine teeth that hold onto prey before swallowing. They are located in the front of the upper jaw, in pairs of tiny clusters. .

The bodies of Chinese giant salamanders are heavily built and flat, with short limbs, a dorsal fin running from their bodies to their tails, and large, flat compressed tails that make up 59 percent of their total body length. Their tail is flat. teeth. Their skin is rough and porous and can be dark brown, green, or black in color. Irregular marbled markings are found on the skin. Larvae resemble adult individuals in shape. There is no geographic or seasonal variation reported.

Chinese Giant Salamander Food, Hunting and Predators

Chinese giant salamanders are carnivores (eat meat or animal parts) but are also recognized as piscivores (eat fish) and insectivores (eat insects). The mainly eat fish, crabs, frogs, water shrews, snakes, other aquatic animals and Chinese giant salamanders. [Source: Lauren Hatch, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

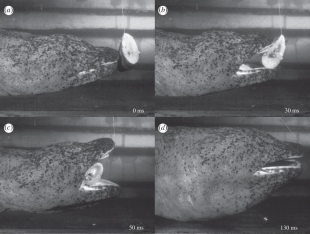

Chinese giant salamanders are ambush predators. They don't seek and attack prey but rather open their mouth to wait for their prey to enter their mouth, and then slam it shut. When prey is near their mouth they employ buccal suction. The elastic cartilage in their jaws is shaped so that one side of their mandible becomes severely depressed, which causes asymmetrical suction. Prey is then sucked into their mouths.

Chinese giant salamanders are highly cannibalistic. Members of their own species have been to make up up to 27 percent of their diet by weight. Twigs, leaves, and gravel have also been found in their stomachs, though that is thought to be ingested while capturing prey or serves a digestive function. (Browne, et al., 2014; Nickerson, 2004) /=\

Chinese giant salamanders are apex predators. Their only known natural predators are humans and other members of their species. Even so the have good defenses: good camouflage and skin secretions comprised of an acidic, sticky substance that repels predators.

Chinese Giant Salamander Behavior

Chinese giant salamanders are natatorial (equipped for swimming), nocturnal (active at night), motile (move around as opposed to being stationary), sedentary (remain in the same area), territorial (defend an area within the home range) and solitary. They are most active during the mid-evening. Territorial behavior becomes more pronounced during breeding season. Conflicts that result in serious injury or death are not uncommon if an individual enters the home range of a rival. [Source: Lauren Hatch, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

The immediate territory within their home range that Chinese giant salamanders defend is around 30 square meters for females and 40 30 square meters for males. Large ones that roam around in are up to 1,150 square meters. Females usually have smaller home ranges than males. Though they are sedentary animals, they frequently move around their larger home range. The average daily distance a salamander moves is 300 meters, but they can move up to 700 meters in a single day. If displaced from their home range due to natural disasters such as a flood, Chinese giant salamanders will keep moving until they find another suitable replacement. habitat.

Chinese giant salamanders sense using sound, vibrations and chemicals usually detected with smelling or smelling-like senses.They communicate with sound and chemicals and employ pheromones (chemicals released into air or water that are detected by and responded to by other animals of the same species) and vibrations. Chinese giant salamanders communicate vocally using hisses, whistles, barks and cries. They have poor eyesight and rely on vibrations that they sense using nodes found on the sides of their bodies to move around their environment. These vibrations help them sense prey and other salamanders as well as objects./=\

Chinese Giant Salamander Metamorphisis and Life Cycle

The development and lifecycle of Chinese giant salamanders is characterized by metamorphosis and indeterminate growth (they continue growing throughout their lives). Metamorphosis is the process of development in which individuals change in shape or structure as they grow. /=\

Chinese giant salamanders have three stages in their development and metamorphosis: 1) egg, 2) larval, and 3) adult. Eggs hatch 40 to 60 days after fertilization. Tadpoles are 3.5 centimeters long with developed branchia. A month after hatching, they have fully developed forelimbs and posterior limbs. Toe differentiation in the limbs develops gradually. Lungs start to develop and after eight months, branchia start to degenerate and metamorphosis begins. One or two years after branchial degeneration begins, their branchia are completely gone and they are completely reliant upon their lungs. /=\

Metamorphosis ends when Chinese giant salamanders are around 2.5 or three years old. They reach maturity and enter adulthood at approximately five or six years of age and 40 to 50 centimeters in length. As they exhibit indeterminate growth they continue grow at a set pace after they reach maturity,

Chinese Giant Salamander Mating, Reproduction and Offspring

Chinese giant salamanders are monogamous (having one mate at a time) and polygynous (males have more than one female as a mate at one time). They are oviparous (young are hatched from eggs) and reproduction is external (the male’s sperm fertilizes the female’s egg outside her body). Chinese giant salamanders breed once a year, with the breeding season being in August and September. The number of eggs laid ranges from 300 to 560, with the average number being 350. The time to hatching ranges from 40 to 60 days, with independence occurring on average at one days. Females and males reach sexual or reproductive maturity at five to seven years.[Source: Lauren Hatch, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

The Chinese giant salamanders breeding season begins when males enter individual dens in August. These dens are usually pre-existing aquatic caves or cavities. Males engage in a behavior called 'sand-pushing' where they push sand and gravel out of their dens. Sand-pushing can last for eight days and, once completed, their dens are smooth and clean. Clean dens attract females. Males also 'shower' themselves. They leave their dens and rinse their bodies, which causes them to release hormones, promotes testis development, initiates courtship and attract females.

Courtship occurs about one month before eggs are laid and comprises eight behaviors: 1) knocking bellies, 2) side-by-side behavior, 3) cohabitating, 4) riding, 5) mouth-to-mouth posturing, 6) chasing, 7) inviting, and 8) rolling over. Cohabitating — where males and females live in the same den — occurs about 88 percent of the time and is the mating behavior used most frequently. After courtship occurs and Chinese giant salamanders find suitable partners, oviposition is accomplished. Males then fertilize eggs after they have been produced and laid on rocks or in caves or cavities underwater by females. The eggs are seven to eight millimeters in diameter. After laying the eggs the females’ reproduction duties are finished. They have not been observed participating in parental care after this. /=\

Parental care is provided by males who are referred to as den masters. After fertilization, males protect and care for the eggs. They observe their eggs to make sure they develop correctly. They accomplish this by tail-fanning, agitating the eggs, shaking, and egg eating. Tail-fanning is employed most and is done to increase the water flow and amount of dissolved oxygen in the water, which is needed for optimal embryonic development. Agitating eggs accomplishes the same goal. Shaking, which is when fathers shake the trunks of their bodies, prevents the eggs from becoming infected by water mold and prevents yolks from sticking to the shells. Males eat unfertilized, yolk-stuck, and water-mold-infected eggs.

Parental care by Chinese giant salamanders takes place during pre-hatching. Once eggs are hatched, larvae are independent of their parents.After hatching, larvae develop in the streams that they will reside in once they reach adulthood. Young salamanders hatch quickly from their eggs — within 21 days naturally — but grow very slowly.

Chinese Giant Salamander, Humans and Conservation

On the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List Chinese giant salamanders are listed as Critically Endangered. On the US Federal List they are classified as Endangered. In CITES (Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild) they are in Appendix I, which lists species that are the most endangered among CITES-listed animals and plants. They are also listed as a Class II Protected Species by the Wildlife Protection Law in China. [Source: Lauren Hatch, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

Between 1980 and 2000, Chinese giant salamander populations declined by 80 percent as a result of habitat loss, overexploitation, habitat fragmentation, loss of genetic diversity and harvesting for the wildlife trade. They can be caught relatively easily by poachers who know what they are doinng and sold to restaurants or farms for hundreds of dollars per kilograms. It is also believed that climate change and warming temperatures have affected their ability to find suitable home ranges.

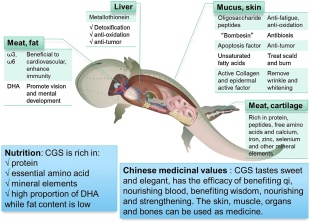

Chinese giant salamanders have traditionally been a source of food and medicine in China. They are considered a delicacy and are both poached and farmed for food. The acidic skin secretion that Chinese giant salamanders produce to repel predators is used for traditional medicinal purposes in China.

There are many domestic and international efforts to help Chinese giant salamanders. Groups like EDGE, Shaanxi Normal University, the Zoological Society of London, and the Darwin Initiative are working on ways to spread public knowledge of Chinese giant salamander conservation. These institutes are looking for ways to conserve the habitats and populations of Chinese giant salamanders.

Giant Salamander Survey Can't Find Any Wild Ones

Rachel Nuwer wrote in the New York Times: The Chinese giant salamander has quietly slipped toward extinction in nature. Following an exhaustive, yearslong search, researchers recently reported that they were unable to find any wild-born individuals.“When we started the survey, we were sure we’d at least find several salamanders,” said Turvey. “It’s only now that we’ve finished that we realize the actual severity of the situation.” As with so many other protected species in China, poaching is the main threat to giant salamanders. “Professor Samuel Turvey, of the ZSL and lead author of the study published today in Ecology and Evolution journal said: “The decline in wild Chinese giant salamander numbers has been catastrophic, mainly due to recent overexploitation for food. [Source: Rachel Nuwer, New York Times, June 4, 2018]

Realizing the amphibians were disappearing in nature, officials decided to restock wild populations by releasing captive-born salamanders. Until now, the cumulative effect of poaching, farming and release on wild populations was unknown. So in 2013, Dr. Turvey and his colleagues organized a nationwide giant salamander search — apparently the largest wildlife survey ever conducted in China. They spent three years scanning riverbeds and turning over rocks at 97 sites in 16 provinces. They found giant salamanders at just four sites. All of the animals had genetic profiles that did not match the places in which they were living, indicating they likely originated on farms.

The researchers also interviewed nearly 3,000 local people, about half of whom said they had seen giant salamanders in the wild. But the most recent sightings they could recall took place, on average, 18 years ago. “There could be remnant populations of genuine salamanders scattered here and there, but they are effectively impossible for any researchers to find now,” Dr. Turvey said. “If we wait too long, all those wild-caught individuals will be gone,” he said.

Releases of giant salamanders without knowing their genetic makeup should stop immediately, Dr. Che added. But that can’t happen without buy-in from Chinese authorities. “We hope to work with the government to improve the existing conservation plan,” Dr. Che said. “We have a responsibility to do conservation based on scientific knowledge.”

Giant Chinese Salamander Farms

Most giant salamanders are now found on farms in China. There are numerous places that farm and breed them. Millions of them are bred for their meat in such farms scattered throughout China. Salamander meat was marketed as a luxury food item in the 1990s, and government-subsidized farms spread around the country. But it wasn’t always that way. Unlike pangolins and tigers, salamanders were never historically valued for their meat or as a medicine. “Traditional knowledge associated them with bad luck and dead babies,” Samuel Turvey, a giant salamander expert at the Zoological Society of London, said. “They were animals you didn’t want to go near.” [Source: Rachel Nuwer, New York Times, June 4, 2018]

Rachel Nuwer wrote in the New York Times: That changed in the mid-20th century when famine forced people to turn to alternative food sources. By the 1990s, giant salamander meat had been rebranded as a luxury food item in China, and government-subsidized salamander farms began popping up around the country. As prices for live animals skyrocketed, captive populations grew and wild ones plummeted. “The development of this industry led to huge amounts of increased pressure on salamanders, which were poached from the wild to stock these farms,” Dr. Turvey said.

Ben Tapley, head of the reptile team at the Zoological Society of London (ZSL), told mongabay.com: .The scale of the farming industry in China is staggering — a 2011 census purely looking at the licensed farms in Shaanxi Province showed that there were 2.6 million Chinese giant salamanders on farms, and the industry has expanded massively since then. Diseases such as ranavirus are a problem on some of the farms, and effluent from these facilities often flows directly into neighboring river systems.”

Chinese Officials Dine on Endangered Giant Salamander

In January 2015, AFP reported: “Chinese officials feasted on a critically endangered giant salamander and turned violent when journalists photographed the luxury banquet, according to media reports on the event which appeared to flout Beijing's austerity campaign. The 28 diners included senior police officials from the southern city of Shenzhen, the Global Times said. "In my territory, it is my treat," it quoted a man in the room as saying. [Source: AFP, January 28, 2015 ]

“The giant salamander is believed by some Chinese to have anti-ageing properties, but there is no orthodox evidence to back the claim. The species is classed as "critically endangered" on the International Union for Conservation of Nature's (IUCN) Red List of threatened species, which says the population has "declined catastrophically over the last 30 years". "Commercial over-exploitation for human consumption is the main threat to this species," the IUCN said.

The Global Times cited the Guangzhou-based Southern Metropolis Daily, which said its journalists were beaten up when their identities were discovered by the diners. One was kicked and slapped, another had his mobile phone forcibly taken, while the photographer was choked, beaten up and had his camera smashed, the reports said.

A total of 14 police have been suspended and an investigation launched into the incident, added the Global Times. One of the Shenzhen diners provided the salamander and said it had been captive-bred, according to the report. Chinese President Xi Jinping has launched a much-publicised austerity drive for the ruling classes, including a campaign for simple meals with the catchphrase “four dishes and one soup”.

Restaurant Fined for Charging Outrageous Prices for Giant Salamander

In 2016 , a restaurant in Guangxi region has been fined 500,000 yuan ($77,000 dollars) for its outrageously-priced giant salamander. The China Daily reported: The restaurant also had its business and service licenses revoked, according to Guilin government. A tourist, identified as Wang, was left up in arms after she was charged a staggering 5,000 yuan for a giant salamander weighing 1.65 kg. "I was taken to the restaurant by a taxi driver," she said. "The waiter recommended the giant salamander, but they did not specify the price." "It was not until after the cook had killed the animal that they told me it would cost 3,200 yuan a kilo, and offered a discount if I didn't request an invoice," Wang said. "It's ridiculous! The highest price I have heard people paying for a giant salamander in Guilin was 1,400 yuan per kilo."[Source: China Daily, April 26, 2016]

Wang informed the police, who helped her barter the price down to 1,500 yuan. The restaurant, however, offered a very different story. "Every dish is clearly labeled with a specific price," said a waiter, who declined to be named. "The salamander was not killed until she accepted the weight and price." The restaurant manager told Xinhua that they bought the giant salamanders at a local vegetable market for around 700 yuan per kilo. He added that all prices were set within the restaurant's rights.

According to the Pricing Law, restaurants must not over-price their products. Another regulation also stipulates that the price of a certain commodity or service must not exceed the average price for the same area. It transpires that the restaurant has form in this regard. Customers last year complained about its prices, so it changed its name, according to investigators.

How Giant Salamander Farms Are Harming the Species

The farming of giant salamanders can be detrimental to populations as they depletes the genetic diversity of the species. Depleted genetic diversity can cause disease outbreaks like Ranavirus to be more common. Farmed giant salamanders released into the wild are genetically distinct from those that evolved naturally and are considered a man-made “species.” Dr. Turvey said that reintroducing farmed animals is not a simple solution for saving the species in the wild and in fact may be harmful. “The farms are driving the extinction of most of the species by homogenizing them,” said Robert Murphy, a senior curator of herpetology at the Royal Ontario Museum. “We’re losing genetic diversity and adaptations that have been evolving for millions of years.”

giant salamander

On farms, the five to eight species of giant salamander are being muddled into a single hybridized population adapted to no particular environment. Rachel Nuwer wrote in the New York Times: Not recognizing that salamanders from different parts of the country were distinct species, farmers had inadvertently created hybrids — a fact that the researchers confirmed through genetic analysis of over 1,000 captive amphibians. “When we looked at farmed animals, we found a large mixture of different genetic components, like a witch’s caldron,” said Jing Che, a herpetologist at the Kunming Institute of Zoology and co-author of both recent studies. [Source: Rachel Nuwer, New York Times, June 4, 2018]

No system was ever put in place to prevent hybrids from release into the wild, nor to ensure that reintroduced animals were matched with their geographic origins. “These hybrids may create a big mess by changing the genetic makeup of locally adapted wild animals,” Dr. Che said. In 2009, Dr. Murphy and his colleagues raised these concerns at a government meeting but were dismissed. “They just said it wasn’t an issue,” he said. At least 72,000 captive-bred salamanders have been released since then.

Japanese Giant Salamanders and Chinese Giant Salamanders

The Japanese giant salamander can reach lengths of over a meter and can live almost 100 years. It almost as big as the Chinese giant salamander, the world’s largest amphibian, which reach lengths of a meter and a half. Japanese giant salamanders live mainly in rivers in central and western parts of Honshu as well as Shikoku and Kyushu. They used be hunted for food and traditional Asian medicines but now are protected by law, having been designated a special natural monument in 1952.

Chinese giant salamanders and Japanese giant salamanders are very difficult to tell apart. Before an international ban on trade of these salamanders came into effect many Chinese giant salamanders — which are raised in farms in China for human consumption — were imported live to Japan for food. One dealer in Okayama obtained 800 of them for sale to restaurants. Some of those that were imported escaped or were released and have interbred with the Japanese species and competed with them for nesting sites and food.

Japanese giant salamander Many of the Japanese giant salamanders seen in rivers in central and western Japan are actually Chinese giant salamanders, which biologists regard as threat to their Japanese cousins. DNA analysis of giant salamanders caught in the wild reveal that many are Chinese not Japanese, with some Chinese ones even showing up in the Tokyo area. One 140-centimeter Chinese giant salamander in the 1990s in Saitama Prefecture’s Arakawa River is still alive and is the largest salamander in captivity in Japan.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Animal Diversity Web animaldiversity.org ; National Geographic, Live Science, Natural History magazine, CNTO (China National Tourism Administration) David Attenborough books, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Discover magazine, The New Yorker, Time, BBC, CNN, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Wikipedia, The Guardian, Top Secret Animal Attack Files website and various books and other publications.

Last updated March 2025