CULTURE AND ARTS IN MONGOLIA

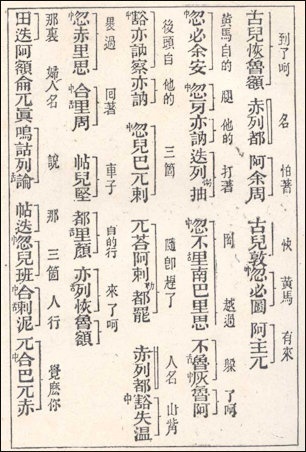

page from the "Secret History of the Mongols"

Art forms with uniquely Mongolian elements include music, dance, clothing, crafts and literature. Mongolian literature, music and other art forms have traditionally celebrated Mongolia’s animals and land. Art and architecture have been influenced by Chinese and Tibetan culture. Mongolians use a Chinese-Tibetan-style calendar and Chinese abacus. The government has traditionally supported opera, ballet, folk dancing, folk music and circuses. But there is not is much money for these things any more. Many of these art forms were introduced by the Soviets.

Mongolian culture is noted for its epic poetry and music. Russian folk songs and dances, performed in Mongolian, used to be popular. Traditional Mongolian society was affected heavily by foreign influences: commerce was controlled by Chinese merchants and the state religion — Tibetan Buddhism or Lamaism — was simultaneously bureaucratic and otherworldly. Modern society has been shaped by the continued foreign — primarily Soviet — influence. [Source: Robert L. Worden, Library of Congress, June 1989 ]

William Jankowiak, Ian Skoggard, and John Beierle wrote: Mongolian artisans were honored and respected. They worked in gold, silver, iron, wood, leather, and textiles. They prefer to use lavish ornamentation and motifs with symbolic meanings associated with nature. Festival clothing is bright and colorful. Mongolians adopted many Tibetan Buddhist elements in their fine arts. Unlike Zen-inspired monochromatic painting of Japan and China, Mongolian art is solidly painted and bold in its designs. The applied arts have increased in importance because of export demands and tourist preference. [Source: William Jankowiak, Ian Skoggard, and John Beierle, e Human Relations Area Files (eHRAF) World Cultures, Yale University]

The communist government did not value Mongolian traditional art works. Much of that art was lost with the purging of Buddhism. In old Mongolia, music styles, dance performances, texts, and iconography were used to express ethnic identity. Given Mongolia's regional diversity, there was variation in songs as well as in instrument style. Herders, like other Central Asian pastorals, played predominately string or wind instruments. Songs are closely linked to old homelands, migrations, nature spirits, or former administrators, such as princes and lamas. Certain types of performance were thought to have control over the weather. Under communism these themes were forbidden. New songs and poems about nature, the homeland, love of parents, children, the state, and the Party became the preferred themes. In terms of music structure, Mongolian traditional songs fall along a continuum that range from extended long songs that are ornamental and without a regular beat. At the other end are strophic, syllabic, rhythmic short-songs performed without ornamentation.

See Separate Articles: TRADITIONAL MONGOLIAN MUSIC factsanddetails.com ; KHOOMEI (THROAT SINGING): SINGING TWO TONES SIMULTANEOUSLY factsanddetails.com ; MONGOLIAN HIP HOP, ROCK POP MUSIC AND DANCE factsanddetails.com MONGOL ART, CULTURE AND LITERATURE factsanddetails.com

Mongol Influence on the World

Mongolia and the Mongol people have periodically been at the center of international events. The histories of nations — indeed, of continents — have been rewritten and major cultural and political changes have occurred because of a virtual handful of seemingly remote pastoral nomads. The thirteenth-century accomplishments of Chinggis Khan in conquering a swath of the world from modern-day Korea to southern Russia and in invading deep into Europe, and the cultural achievements of his grandson, Khubilai Khan, in China are well-known in world history. Seven hundred years later, a much compressed Mongolian nation first attracted world attention as a strategic battleground between Japan and the Soviet Union and later between the Soviet Union and China. In the 1980s, the Mongolian People's Republic continued to be a critical geopolitical factor in Sino-Soviet relations. [Source: Robert L. Worden, Library of Congress, June 1989 *]

But Mongol influence did not end with the termination of military conquests or absorption. Their presence was institutionalized in many of the lands they conquered through adoption of Mongol military tactics, administrative forms, and commercial enterprises. The historical developments of such disparate nations as Russia, China, and Iran were directly affected by the Mongols. Wherever they settled outside their homeland, the Mongols brought about cultural change and institutional improvements. *

Although there never was a "Pax Mongolica," the spread of the Mongol polity across Eurasia resulted in a large measure of cultural exchange. Chinese scribes and artists served the court of the Ilkhans in Iran, Italian merchants served the great khans in Karakorum and Daidu (as Beijing was then known), papal envoys recorded events in the courts of the great khans, Mongol princes were dispatched to all points of the great Mongol empire to observe and be observed, and the Golden Horde and their Tatar descendants left a lasting mark on Moscovy through administrative developments and intermarriage. Although eventually subsumed as part of the Chinese empire, the Mongols were quick to seek independence when that empire disintegrated in 1911. *

Cultural Unity and Mongol Identity in the Soviet Era

Letter from Kubla Khan to the "King of Japan"

The result of Mongolia's economic development and urbanization was a population that was, on the one hand, increasingly and unprecedentedly divided by occupation, education, residence, and membership in well-defined and fairly rigid status groups, but that was, on the other hand, less clearly distinguished from that of other economically developed and urbanized countries. If being Mongolian meant living in a ger in the midst of a sheep herd and being good at riding horses, then the Mongolian identity of those who lived in highrise apartments, rode buses, and worked at desks or in factories where knowledge of the Russian language was required was problematic. [Source: Robert L. Worden, Library of Congress, June 1989 *]

Mongolian nationalism, clearly a politically sensitive topic, continued to be a strong although implicit force in Mongolia in the Soviet era. The Mongol language, the cultural trait most obviously shared by all Mongolians, continued to be fostered. Much effort was devoted to translating foreign literature and textbooks into Mongol, and teams of Mongolian scholars carefully replaced Russian loan words with new terms developed from ancient Mongol roots. The goal appeared to be to ensure that Mongol did not become a dialect restricted to shepherds or preschool children and that the educated elite did not speak mostly Russian or Russian-influenced Mongol.

Apart from the significant omission of Buddhism and Buddhism, much of traditional Mongol culture was studied, preserved, and transmitted to the younger generation as a source of national pride. In early 1989, party general secretary Jambyn Batmonh told a Soviet interviewer that the harmful errors of the 1930s included destruction of the monasteries and with them the priceless cultural heritage of the Mongolian people. In 1989 the party called for overcoming indifference to the national cultural heritage, and efforts were under way to change the negative evaluation of Chinggis, who had been condemned as a bloodthirsty and aggressive conqueror of, among other places, Russia. Higher secondary schools began teaching the traditional Mongol script, replaced by Cyrillic in February 1946. In early 1989, the trade union newspaper Hodolmor (Labor) called for mass production of the traditional Mongol gown, the deel, and suggested that all Mongolian diplomats wear it.

Mongolian Literature and Folklore

The majority of Mongol literature is Buddhist, and the whole Buddhist Canon was translated from Tibetan to Mongol. There exists also a very fine collection of original historical literature that includes the Secret History of the Mongols written in the middle of the 13th century and various other chronicles, such as that of Saghang Sechen written in the second half of the 17th century, the heroic epic “Life of Jiangger," written in the fifteenth century, and “Historical Romance," written in the nineteenth century.

Mongolia has a tradition of epic poetry that was first written down in the Genghis Khan era and is closely associated with its music ( See Music). The canon of Mongolian written literature includes histories, biographies and Buddhist texts on a number of subjects. Some Buddhist sutras are elaborately decorated with gold and jewels. The State Central Library in Ulaanbaatar holds the world’s largest collection of Buddhist sutras.

Mongolia's best known poet and writer is Dashdorjiin Natsagdorj (1906-37). He is regarded as the father of modern Mongolia literature. His best known works include the nationalist poem “My Native Land” and the play “Three Fateful Hills”. He served as a secretary in the Stalinist government and died under mysterious circumstances in 1936. The location of his body and grave is not known.

C. Le Blanc wrote in the “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life, “A large number of Mongolian myths are related to the origins of the Mongol people. One of their more important myths describes a tribe called Mongu fighting with other tribes for many years. Finally, the Mongu were defeated. All their people were killed except two men and two women who, by sheer luck, escaped death. They went through many hardships and ultimately took refuge in a remote, thickly forested mountain. Only a narrow winding trail led to the outside world. This was a place with plenty of water and lush grass. They married. Many years later, the population grew so large that the land could not produce enough grain to feed all the people. They had to move but, unfortunately, the narrow trail was blocked. However, an iron mine was discovered. They cut down the trees, killed bulls and horses, and made a number of bellows to use in making iron into tools. Then they began to work the mine. They not only opened an outlet to the outside world, but they also got plenty of iron. They are the ancestors of the Mongols. To commemorate their heroic undertakings, the Mongols used to smelt iron at the end of every year. [Source: C. Le Blanc, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009 ++]

The Gesar epic tradition was inscribed in 2009 on the UNESCO Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity. According to UNESCO: The ethnic Tibetan, Mongolian and Tu communities in western and northern China share the story of the ancient hero King Gesar, sent to heaven to vanquish monsters, depose the powerful, and aid the weak while unifying disparate tribes. The singers and storytellers who preserve the Gesar epic tradition perform episodes of the vast oral narrative (known as ‘beads on a string’) in alternating passages of prose and verse with numerous regional differences. [Source: UNESCO]

See KING GESAR: TIBET’S GREAT HEROIC EPIC factsanddetails.com ; MONGOL ART, CULTURE AND LITERATURE factsanddetails.com

Mongol Tuuli, the Mongolian Epic

In 2009, Mongol Tuuli, Mongolian epic was placed on the UNESCO Intangible Heritage list. According to UNESCO: “The Mongolian Tuuli is an oral tradition comprising heroic epics that run from hundreds to thousands of lines and combine benedictions, eulogies, spells, idiomatic phrases, fairy tales, myths and folk songs. They are regarded as a living encyclopaedia of Mongolian oral traditions and immortalize the heroic history of the Mongolian people. Epic singers are distinguished by their prodigious memory and performance skills, combining singing, vocal improvisation and musical composition coupled with theatrical elements. Epic lyrics are performed to musical accompaniment on instruments such as the morin khuur (horse-head fiddle) and tovshuur (lute). [Source: UNESCO ~]

“Epics are performed during many social and public events, including state affairs, weddings, a child’s first haircut, the naadam (a wrestling, archery and horseracing festival) and the worship of sacred sites. Epics evolved over many centuries, and reflect nomadic lifestyles, social behaviours, religion, mentalities and imagination. Performing artists cultivate epic traditions from generation to generation, learning, performing and transmitting techniques within kinship circles, from fathers to sons. Through the epics, Mongolians transmit their historical knowledge and values to younger generations, strengthening awareness of national identity, pride and unity. Today, the number of epic trainers and learners is decreasing. With the gradual disappearance of the Mongol epic, the system of transmitting historic and cultural knowledge is degrading. ~

According to UNESCO Mongol Tuuli, Mongolian epic was placed on the UNESCO Intangible Heritage list because: 1) A living oral expression that is crucial for the cultural identity of the Mongolian people and for the historical continuity of their nomadic lifestyle, the Mongol Tuuli epic plays an important role in the traditional education of younger people living in the communities where it is performed; 2) Although Mongolian singers continue to attach great importance to performing the epic within traditional contexts and in sacred settings, and endeavour to transmit performing techniques to the younger generation in the manner learned from their ancestors, the epic is today at severe risk because of its shrinking social sphere, changing socioeconomic conditions and the weakening of nomadic practices, the difficulties for younger people to master the complex poetic language, and the increasing popularity of mass entertainment media, [Source: UNESCO]

Galsansuh

Bill Donahue wrote in the Washington Post, “Galsansuh, 40, is a self-proclaimed “postmodern Mongolian poet”; the editor of Serious News, a UB broadsheet that rails with anarchist brio against corrupt politicians; and a mogul on UB’s alt-rock scene. It is he who, 15 years ago, gathered the musicians for Nisvanis, a Mongol take on Nirvana. Lean and crew-cut, he speaks in harsh, vitriolic bursts. [Source: Bill Donahue, Washington Post, September 20, 2013 |::|]

“Class warfare,” says Galsansuh, except that I can hardly hear him as Kreator, a German thrash metal band, is screaming on the stereo of his Land Cruiser as we cut through the streets of UB...“Class warfare,” he says again, en route to a Korean restaurant, and I’m a bit bewildered. The underclass in Mongolia is disparate: 400,000 or so herders speckling the steppes and the desert. No one else I’ll meet will speak of uniting them. But there is something absolute about Galsansuh. Driving through UB, he guns it wherever he can. He slams the brakes in advance of a pothole, then swirls right into a dirt alley to skirt a traffic jam and flies along through a parking lot. |::|

“Though he carries himself like a cartoon villain, Galsansuh is powerful, and connected. His good friend Kh.Battulga is a wealthy parliament member, a one-time national judo champion and the lead financier for the gargantuan Genghis statue 35 miles outside town. “Mongolian national hero,” Galsansuh says of Battulga as we settle into the restaurant. “He has no Chinese blood — he is pure Mongolian. And that statue of Chinggis Khan [Ghengis Khan], it’s a tool we need to keep us from becoming part of China.” |::|

“In the meantime, Galsansuh is fighting. He opens his newspaper up on the table now, and all five guys on the front page look fat and pasty, like boiled fish. They radiate bad karma. I recognize one of the shysters as Mongolia’s most recent ex-president, the imprisoned N. Enkhbayar. While he was in office, Enkhbayar secretly financed the construction of the 25-story Blue Sky Tower, a soulless glass building — blue-tinted and shaped like a sail — that sits in downtown UB, looming above the red-tiled roof of an ancient pagoda. |::|

“The Blue Sky Tower is on my Mongolian cellphone — the default screen saver is the glassy and glimmering flank of the tower. I show it to Galsansuh and ask, “Have Mongolians become too enchanted with glitz and material wealth to care?” He is smoking now and clenching the cigarette in his lips, no fingers. “I don’t have time for such silly questions,” he says. He snatches the bill and pays. Then we leave.

Mongolia Art

Most Mongolia art has been inspired by Tibetan Buddhism or shamanism and resembles Tibetan art. Artworks include golden Buddhist icons, Tibetan-style frescos, pictorial applique and shamanist masks and implements. Much of Mongolia’s old art has been lost. The Buddhist destroyed shamanist art as they attempted to make their belief the dominant one. Stalinist purges in the 1930s made ruins of practically all of Mongolia’s 700 monasteries and all the art in them.

Mongolian thankas (Tibetan-style cloth paintings) are made with chalk, glue, “arkhi” (milk vodka) and minerals mixed with yak skin glue. For the most part they look like Tibetan thankhas except some have some camels in the background. There are some from the Soviet era that feature factory workers and miners.

Art produced the Soviet period was influenced a great deal by socialist realism and Russian impressionism. Many artists studied art in the Soviet Union.

See Separate Articles on Tibetan Art factsanddetails.com and factsanddetails.com and factsanddetails.com .

Zanabazar and Other Mongolian Artists

Zanabazar (1635-1723) is Mongolia’s famous leader from the post-Mongol-empire period. Regarded as the first The Jebtzun Damba, the Living Buddha of Mongolia, he was declared leader of the Buddhists in Mongolia in 1641. He was not only a great political and religious leader he was is also regarded as Mongolia’s most famous artist and sculptor. Trained in Tibet, he created lovely Buddhist paintings and thankas, invented Mongolia’s vertical script, designed great temples, and produced beautiful bronze statues. Some of his loveliest pieces are of goddess Tara. They are said to have been modeled after his teenage lover.

When Zanabazar was three it was deemed he possessed the qualities of a reincarnated saint. At the age of 13 he was sent to Tibet to study under the Dalai Lama. While in Tibet he not only received spiritual guidance he learned the art of bronze casting which launched his career as an artist. He is credited with inventing the Soyombi, Mongolia’s national symbol. He died in 1723 in Beijing. His body was taken to what would be Ulaanbaatar and later was entombed in stupa at Amarbayasgalant Monastery. Zanabazar is an object of art as well as an artist. Images of Zanabazar are seen throughout Mongolia. They are easily recognizable: a monk with a shiny bald head and a thunderbolt in one hand.

Another well known lamas was Danzan Ravjaa, also known as the Great and Horrible Saint of the Gobi. Believed to be the 35th incarnation of Yamsang Yidam, a Mongolian deity, he was a skilled artist and was known for producing plays at monasteries and healing the sick from great distances. He lived in the 19th century. Among the other famous artists are the artist-monk Damdinsuren (1868-1938) and the painter Balduugiyn Shara (1869-1939). The later is known for his paintings of every day Mongolian life.

Mongolian Calligraphy

In 2013, Mongolian calligraphy was placed on the UNESCO Intangible Heritage list. According to UNESCO: Mongolian calligraphy is the technique of handwriting in the Classical Mongolian script, which comprises ninety letters connected vertically by continuous strokes to create words. The letters are formed from six main strokes, known as head, tooth, stem, stomach, bow and tail, respectively. This meticulous writing is used for official letters, invitations, diplomatic correspondence and love letters; for a form of shorthand known as synchronic writing; and for emblems, logos, coins and stamps in ‘folded’ forms. [Source: UNESCO ~]

Traditionally, mentors select the best students and train them to be calligraphers over a period of five to eight years. Students and teachers bond for life and continue to stimulate each other’s artistic endeavours. The rate of social transformation, urbanization and globalization have led to a significant drop in the number of young calligraphers. At present, only three middle-aged scholars voluntarily train the small community of just over twenty young calligraphers. Moreover, increases in the cost of living mean that mentors can no longer afford to teach the younger generation without remuneration. Special measures are therefore needed to attract young people to the traditional art of writing and to safeguard and revitalize the tradition of Mongolian script and calligraphy. ~

Mongolian calligraphy has experienced a rebirth since the democratization of Mongolia in the 1990s, after decades of suppression. However, according to UNESCO Mongolian calligraphy was placed on the UNESCO Intangible Heritage list because: 1) Mongolian calligraphy provides a sense of identity and historical continuity to Mongolian people at large; revived with the establishment of democracy in the 1990s, the practice has pertinent social and economic functions for its bearers in the contemporary context; 2) The viability of Mongolian calligraphy is at risk because of the limited number of tradition bearers who transmit their knowledge, the absence of appropriate safeguarding policies and the lack of interest by the young generation.

Living Dioramas in the Mongolian Desert

Paris-based Korean photographer Daesung Lee produced a series of “Living Dioramas in the Mongolian Desert”: Rachel Nuwer wrote in The New Yorker, “As part of an ongoing series exploring the cultural effects of climate change...Lee recently set out to capture Mongolia’s transformation. But rather than documenting picturesque pastoralists at home in the Gobi Desert, or the squalor of Ulaanbaatar’s ger district, Lee created and photographed living dioramas that vividly juxtapose the old Mongolian landscape and the new. [Source: Rachel Nuwer, The New Yorker, May 5, 2015 /]

“The photos in the series, entitled “Futuristic Archaeology,” show billboard-sized backdrops of past or future landscapes erected in the countryside: images of grasslands stand in the desert, cordoned off behind velvet ropes; pictures of sandy slopes are set against a still-lush steppe. Former nomads, recruited with the help of a local environmental N.G.O., enact scenes—of hunting, herding, and, in one case, Mongolian wrestling—in the contrasting artificial and actual scenery. Dressed in traditional deel robes, the nomads seem frozen in time, like displays in a natural-history museum. In one image, an older couple gazes from the confines of their roped-off square at a man, woman, and two small children clad in jeans and T-shirts. The elders seem like otherworldly visitors from the past. The modern family, and the arid sands around them, appear as embodiments of Mongolia’s present and future. /

Nick Kirkpatrick wrote in the Washington Post, “Lee didn’t want to document as much as he wanted to preserve. To create the museum’s dioramas scientists and artists would spend sometimes months traveling to take pictures and collect specimens before painstakingly creating a picture of a faraway place piece-by-piece, preserving a moment frozen in time. Lee’s dioramas show what would happen if traditional Mongolian culture fades away and is only seen inside a museum. “The nomadic life in Mongolia better alive … I thought that we better preserve the society and the culture,” Lee told In Sight. That culture can then have “function and meaning” instead of being “preserved like a fossil in museum,” he said. [Source: Nick Kirkpatrick, Washington Post, February 18, 2015]

Crafts of Mongolia

Historically, Mongol craftsmen and artisans were greatly respected. After raiding a city the Mongols often rounded up the craftsmen and had them sent back to Mongolia. Traditional Mongol crafts and clothes include ornate silver bridles and saddles, adorned with semi-precious stones, two-stringed musical instruments with green horse heads, decorated and embroidered boots and other items made with leather, fur, textiles, wood, gold, silver and iron.

Jewelry has traditionally been valued as a means of storing wealth, displaying status and expressing beauty. Valuable object have traditionally been passed down to daughters part of their dowery. Amulets were used by shaman in religious rites. The most spectacular pieces were worn by the aristocracy. The most elaborate of these were the thick rope-like necklaces and headdress worn by nobles. Pieces kept by nomads tend to be everyday items such as saddles and belts that could be easily transported.

According to the “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,”“Snuff-bottles are treasured among the Mongolians. They are made of gold, silver, copper, agate, jade, coral, or amber, with fine relief (raised carving) of horses, dragons, rare birds, and other animals. Another artifact is the pipe bowl, made of five metals, with delicate figures and designs. Supplemented by a sandalwood pole and red agate holder, the pipe bowl is considered precious. According to a Mongolian saying, “A pipe bowl is worth a sheep." [Source: C. Le Blanc, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009 ++]

Some of most awesome examples of Mongolia art are large sculptured, vividly-painted masks worn in epic-scale religious dramas. Many of the most demonic ones are actually connected with divine protection, and their intent is to keep evil spirits away. The main attraction of the Tsam (Cham) dance for many non-Tibetans and non-Mongolians is the multitude and diversity of the colorful masks. Masks are the embodiment of the Wrathful Deity. While they drive terror and great fear into the hearts of the forces of evil, the masks also provide tranquility and calm to the Buddhist practitioner who is seeking enlightenment through meditation and prayer. Masks that have survived for a long time are considered special and very powerful. They have become venerated in their own right: with pilgrims praying before them, particularly on special days or during religious festivals.

Tsam dance masks are generally about two or three times the size of a normal human head and quite heavy. Because of their weight, awkward center of gravity, sharp-edge issues, and the possibility of chafing and cuts, dancers wear padded caps or folded towels covering the forehead, sides of the face, and even the neck. The favorite head covering is the toque.

Image Sources:

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, Lonely Planet Guides, Library of Congress, U.S. government, Compton’s Encyclopedia, The Guardian, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, AFP, Wall Street Journal, The Atlantic Monthly, The Economist, Foreign Policy, Wikipedia, BBC, CNN, and various books, websites and other publications.

Last updated October 2022