SAIGA ANTELOPE

Saiga antelope (Saiga tatarica) are steppe animals with a strange-looking snout. True members of the antelope family, they are the size and shape of sheep and have large, bulbous eyes and a nose with a stubby trunk, large nostrils and mucous glands that are so are numerous and large they cause the animal's head to bulge. The purpose of the animals nose features is to warm and moisten the air and filter dust. Saiga are very efficient at converting steppe grasses to meat. Only male saiga antelope have horns. They are simple, amber-colored, straight spikes.

Saigas are medium-size “goat antelopes”. They are well adapted to the harsh conditions of the Eurasian steppe. Their thick hair insulates them in the winter and their elongated noses warm frigid winter air before it reaches the lungs. Their noses have downward-pointing nostrils that are thought to provide help in controlling body temperature, give the animals a keen sense of smell and filter dust. Their thick, wool coat in cinnamon buff, with paler underparts. It thickens considerably in the winter. They eat a variety of plants that grow in the dry steppe.

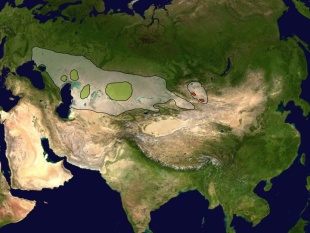

Saiga populations are concentrated in three main areas within central Asia: Mongolia, Kazakhstan, and Kalmykia. They inhabit dry steppes, semi deserts and grasslands and in the past their range stretched from north of the Black Sea to Mongolia. Today they particularly concentrated around the northern Caspian Sea and Kazakhstan. Herds are found in grassy plains void of rugged terrain and hills.

Two subspecies are recognised: 1) Russian saiga (S. t. tatarica), found in central Asia; and 2) Mongolian saiga (S. t. mongolica), endemic to western Mongolia. The latter is sometimes treated as an independent species, or as subspecies of the Pleistocene Saiga borealis. Russian saiga are main the subspecies. They occur only in Kalmykia and Astrakhan Oblast in Russia and in the Ural, Ustyurt and Betpak-Dala regions of Kazakhstan. A portion of the Ustyurt population migrates south to Uzbekistan and occasionally to Turkmenistan in winter. The Mongolian saiga are smaller and stockier than Russian saiga, with horns of a different shape and a slightly more refined proboscis.

Saiga have been around since the last Ice Age, when they ranged across the mammoth steppe from the British Isles to Beringia (Alaska), and evolutionary-wise are distinct from other animals. Stephanie Ward, a conservationist with the Frankfurt Zoological Society, told the BBC, the antelope is among very few living creatures to have run freely among both Neanderthals and the humans of the 21st Century. Saiga live in large herds when conditions allow and have been poached for meat and the male’s amber horns. Saiga are symbol of the Kalmyk steppe — regarded by some as the only steppe in Europe — are a national treasure of the Republic of Kalmykia in Russia.

Saiga sometimes experience huge die-offs (See Below) but have a high birth rate and can bounce back relatively quickly when their populations have been decimated. Two-thirds of pregnant female antelopes give birth to twins. Although the species plummeted to a low of 50,000 saiga in the 1990s, it rebounded with conservation efforts, reaching over 300,000 animals in 2015 when a die-off in Kazakhstan caused numbers to drop to around 100,000.

Sources: Saiga Conservation Alliance and Wildlife Conservation Society.

Bovids

Saiga are bovids. Bovids (Bovidae) are the largest of 10 extant families within Artiodactyla, consisting of more than 140 extant and 300 extinct species. According to Animal Diversity Web: Designation of subfamilies within Bovidae has been controversial and many experts disagree about whether Bovidae is monophyletic (group of organisms that evolved from a single common ancestor) or not. [Source: Whitney Gomez; Tamatha A. Patterson; Jonathon Swinton; John Berini, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

Wild bovids can be found throughout Africa, much of Europe, Asia, and North America and characteristically inhabit grasslands. Their dentition, unguligrade limb morphology, and gastrointestinal specialization likely evolved as a result of their grazing lifestyle. All bovids have four-chambered, ruminating stomachs and at least one pair of horns, which are generally present on both sexes.

Bovid lifespans are highly variable. Some domesticated species have an average lifespan of 10 years with males living up to 28 years and females living up to 22 years. For example, domesticated goats can live up to 17 years but have an average lifespan of 12 years. Most wild bovids live between 10 and 15 years, with larger species tending to live longer. For instance, American bison can live for up to 25 years and gaur up to 30 years. In polygynous species, males often have a shorter lifespan than females. This is likely due to male-male competition and the solitary nature of sexually-dimorphic males resulting in increased vulnerability to predation. /=\

See Separate Article: BOVIDS: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR, SUBFAMILIES factsanddetails.com

Ruminants

Cattle, sheep, goats, yaks, buffalo, deer, antelopes, giraffes, and their relatives are ruminants — cud-chewing mammals that have a distinctive digestive system designed to obtain nutrients from large amounts of nutrient-poor grass. Ruminants evolved about 20 million years ago in North America and migrated from there to Europe and Asia and to a lesser extent South America, where they never became widespread.

As ruminants evolved they rose up on their toes and developed long legs. Their side toes shrunk while their central toes strengthened and the nails developed into hooves, which are extremely durable and excellent shock absorbers.

Ruminants helped grasslands remain as grasslands and thus kept themselves adequately suppled with food. Grasses can withstand the heavy trampling of ruminants while young tree seedlings can not. The changing rain conditions of many grasslands has meant that the grass sprouts seasonally in different places and animals often make long journeys to find pastures. The ruminants hooves and large size allows them to make the journeys.

Describing a descendant of the first ruminates, David Attenborough wrote: deer move through the forest browsing in an unhurried confident way. In contrast the chevrotain feed quickly, collecting fallen fruit and leaves from low bushes and digest them immediately. They then retire to a secluded hiding place and then use a technique that, it seems, they were the first to pioneer. They ruminate. Clumps of their hastly gathered meals are retrieved from a front compartment in their stomach where they had been stored and brought back up the throat to be given a second more intensive chewing with the back teeth. With that done, the chevrotain swallows the lump again. This time it continues through the first chamber of the stomach and into a second where it is fermented into a broth. It is a technique that today is used by many species of grazing mammals.

See Ruminants Under MAMMALS factsanddetails.com

Saiga Characteristics, Diet and Predators

Saiga weigh between 30 and 45 kilograms (66 to 99 pounds). They stand 57 to 78 centimeters (22.5 to 31 inches) at the shoulders and have a head and body length of 108 and 146 centimeters (42.5 to 57.5 inches), with a six-to-12 centimeter (2.4-to-5.1 inch) tail. Their average life span is 10 to 12 years if no massive die off occurs. Sexual Dimorphism (differences between males and females) is present: Males are larger than females and have different ornamentation. Males on average weigh approximately 41 kilograms (90 pounds); females on average wigh 28 kilograms (62 pounds). Only males have horns. [Source: Lauren Pascoe, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

The most noticable feature of a saiga is its large head with a huge mobile nose that hangs over its mouth and has a pair of closely spaced, bloated nostrils directed downward. During summer migrations, saiga noses helo them filter out dust kicked up by the herd and cools the animal's blood. In the winter, it heats up the frigid air before it is taken to the lungs. Males have a pair of long, waxy colored horns with ring-like ridges along their length. Other facial features include the dark markings on the cheeks and the nose, and the 7-to-12 centimeters (2.8-to-4.7 inch) -long ears [Source: Wikipedia]

Except for the unusual snout and horns, Saiga look similar to small sheep. They have long, thin legs and a slightly robust body. During the summer, Saiga have a short coat that is yellowish red on the back and neck with a paler underside. In the winter, the coat becomes thicker and longer. The winter fur is dull gray on the back and neck and a very light, brown-gray shade on the belly. Saiga antelopes also have a short tail. /=\

Saiga antelopes are herbivores. They graze on over one hundred different plant species; the most important of which are grasses, prostrate summer cypress, saltworts, fobs (herbaceous flowering plants), sagebrush, and steppe lichens. Wolves are their main natural predator of adults and young saiga. Foxes, steppe eagles, golden eagles, ravens and stray dogs prey on newborn saigas. /=\

Saiga Behavior

Saiga are motile (move around as opposed to being stationary), migratory (make seasonal movements between regions, such as between breeding and wintering grounds), and social (associates with others of its species; forms social groups). They sense using touch and chemicals usually detected with smell. During the day, saigas graze and visit watering holes. Before resting at night, they dig small circular depressions in the soil to serve as beds. Due to their antelope physiology and unique respiratory system, saiga are one of the world’s fastest terrestrial mammals, capable of reaching speeds of 80 kilometers per hour (50 miles per hour). [Source: Lauren Pascoe, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=\; Russian Tourism Official Website]

Saigas form very large herds that graze in semideserts, steppes, grasslands, and possibly open woodlands, eating several species of plants, including some that are poisonous to other animals. They can cover long distances and swim across rivers, but they avoid steep or rugged areas. When the breeding season is over, small breeding groups join together to form large herds that migrate. Generally, the herds consist of 30 to 40 individuals.

Saigas are known for their extensive migrations across the steppes that allow them to escape natural calamities such as snowstorms and droughts. A portion of the Ustyurt population in Kazakhstan migrates south to Uzbekistan and occasionally to Turkmenistan in winter. In the past, migratory routes ranged throughout Kazakhstan and parts of Russia, especially the region between the Volga and Ural Rivers. Currently, saiga populations' migratory routes pass five countries and different human-made constructions, such as railways, trenches, canals, mining sites, and pipelines hinder movements.

Saiga Mating, Reproduction and Offspring

Saiga polygamous (males mating with several females) and practice seasonal breeding. The gestation period ranges from 4.63 to 5.07 months. The number of offspring ranges from one to three, with the average number of offspring being 1.3, with the average number of offspring being 1.7. The age in which they are weaned ranges from 2.5 to four months. There is an extended period of juvenile learning. On average females reach sexual or reproductive maturity at seven or eight months and males do so at 22 months. [Source: Lauren Pascoe, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

Saiga are adapted to deal with harsh environmental conditions such as severe drought, bitterly cold winters and fire. Females have a high breeding rate. They can mate at the age of four months, when they are not completely grown, and three quarters of them gave birth to twins. The breeding period lasts from late November to late December and starts when saigas congregate into groups consisting of five to 10 females and one male and stags fight for females. Males with harems are very protective of them and those without harems often are desprate to have one. Violent fights often break out between two males. It is not uncommon for males to die in these battles. Winner and dominate males generally lead herds of five to ten females but ones with 50 members have been reported.

In springtime, mothers come together in mass to give birth. Two-thirds of births are twins; the remaining third of births are single calves. Young begin to graze at 4 to 8 days old. Lactation lasts for about four months. In captivity, young saigas occasionally nurse from unrelated adults; however, this has never been observed in the wild. Male saigas grow very weak toward the end of the breeding season. They do not graze at all during the breeding season and spend most of their stored energy defending their harem. As a result, male mortality often reaches 80 to 90 percent. Some are easily killed by wolves.

Endangered Saiga Antelope

On the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List, saiga are listed as Critically Endangered. In CITES (Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild) they are in Appendix II, which lists species not necessarily threatened with extinction now but that may become so unless trade is closely controlled. Currently, the population is rapidly declining due in part to severe poaching. Saiga are protected by the government of Kazakhstan. Measures taken by the Kazakh government to protect the saiga have included a crack down on poaching, with penalties of up to 12 years in prison, and the establishment of nature reserves.

The harsh places where saiga has always made survival Difficult. Many die in blizzards, droughts and periodic die-offs. But humans have made the situation for them much worse. Not only have humans hunted and poached saiga, the fencing of fields and construction of thousands of kilometers of canals, roads and pipelines have disrupted their migration routes and the plowing of natural pastures has reduced the natural vegetation that saiga feed on. Cases of saiga herds being trapped within fenced areas and starving to death have been reported. Current saiga populations are often fragmented, and isolated.

Saiga antelopes are valued for their meat, fur and horns. Their horns have traditionally been ground up and used in Chinese medicine to reduce fevers. Saiga occasionally trample agricultural plants and feed on crops. Up until 1990, they were successfully managed by the Soviet Union. However, the break-up of the Soviet state led to the end of the careful management of saiga populations. [Source: Lauren Pascoe, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

Adam Taylor wrote in the Washington Post, “As was true with the American bisons, saiga numbered in the millions in the 19th century. They could be found from the Caspian Sea in the west to the Gobi desert in the east. Horsemen and other Central Asian people who lived in the steppe loved the taste of saiga meat. It was not unusual for ten thousand animals to be killed in a single hunt. With the introduction of guns they began being killed off at an alarming rate. By 1829, they had been exterminated from much for the middle of their range between the Urals and the Volga. By the beginning of the 20th fewer than a thousand remained. [Source: Adam Taylor, Washington Post, May 29 2015]

There were once 3 million saiga roaming the steppes of Kazakhstan. Now there are only around 150,000. The rest have been lost to hunters, loss of habitat and pollution. Hundreds of thousands of saiga are believed to have died as a result of a single accident in 1985 when a Proton rocket blasting off from the cosmodrome at Baiknonure crashed and sprayed fuel over thousands of square kilometers of steppe. Under the Soviets, hunting saiga was banned and the animals recovered. Within 50 years the number of saiga grew from a few hundred to a two million. In the Soviet era, to keep them from becoming overpopulated a quarter of million were culled every year.

Josh L Davis wrote in iflscience.com: “They were previously heavily hunted, mainly for their horns, which were used as a replacement for rhino in traditional medicine. In a terrible case of poor lack of judgement, the WWF is thought to have had a hand in the decline of the species during the 1990s. At the start of the decade, there were thought to have been around a million of the antelopes roaming the steppes of central Asia, but in a bid to try and ease the poaching of rhinos for their horn, the WWF actually encouraged the use of the saiga horn, leading to their populations to crash. [Source: Josh L Davis, iflscience.com, April 16, 2016]

Over 200,000 Saiga Mysteriously Die in Just a Few Weeks in 2015

In the spring of 2015, 211,000 saigas in Kazakhstan — more than half of the their entire population — were died en masse in less than a month as a result of a bacterial infection. Around the time it happened, Adam Taylor wrote in the Washington Post, “In just a few weeks, vast numbers of the species been found dead – Kazakhstan officials have said that almost 121,000 carcasses have been counted, according to Reuters, a number officials from the United Nations Environment Program (UNEP) have confirmed. For an endangered species, this is dramatic, if not catastrophic. Kazakhstan's has around 90 percent of the world's saiga population... before the deaths began. Experts are clearly shocked. "It is very painful to witness this mass mortality," Erlan Nysynbaev, vice minister of the Ministry of Agriculture of Kazakhstan, said. [Source: Adam Taylor, Washington Post, May 29 2015 |*|]

In 2013, the population of saiga stood at more than 300,000. After the deaths in 2015, there were fewer than 100,000. Josh L Davis wrote in iflscience.com: “It has been estimated that over 200,000 of the animals dropped dead over a matter of days, with scenes of entire herds of the antelope, made up of mothers with calves, littering the landscape...When researchers first discovered the dead and dying animals on the Kazakhstani grasslands, they had no idea as to the scale of the disaster. The first accounts were still shocking, putting the number of dead saiga in the tens of thousands, but as more reports came out conservationists realized the full extent of the die-off. It is thought that as much as 88 percent of the antelope from the Betpak-dala desert of Kazakhstan succumbed, accounting for roughly 70 percent of the entire global population of the already endangered antelope... Before the mass dying, the antelope numbers stood at around 300,000. ” [Source: Josh L Davis, iflscience.com, April 16, 2016]

Andrew C. Revkin wrote in the New York Times: “Hastily bulldozed pits brim with corpses... The enormous new saiga die-off is particularly devastating to conservation biologists because efforts to cut poaching (for meat and “medicinal” horns) were gaining steam in recent years. "It's very dramatic and traumatic, with 100 per cent mortality," Richard Kock of the Royal Veterinary College told the New Scientist from Kazakhstan. "I know of no example in history with this level of mortality, killing all the animals and all the calves," Kock added, noting that the animals die after respiratory problems and extreme diarrhea. [Source: Andrew C. Revkin, New York Times, May 29, 2015]

“The huge scale of the deaths initially left some scientists baffled, and some unusual theories spread – the Kazakhstan's Space Agency have said that they could see no link between the deaths of the animals and a number of Russian space rocket launches near the area they live, though they could not yet rule it out (these launches have already caused some controversy in Kazakhstan). On Thursday, researchers working with the UNEP say that two pathogens, Pasteurella and Clostridia, appeared to be contributing to the die off, but that the animals appear to have already had their immune systems weakened by another unknown factor. |*|

"The death of the saiga antelope is a huge tragedy," zoology scientist Bibigul Sarsenova told Reuters. "Should this happen again next year, they may simply disappear." But the hope is that if the deaths can be controlled or stopped, the animals can bounce back, again. |*|

Previous Saiga Die Offs Offer Clues to What Happened in 2015

Andrew C. Revkin wrote in the New York Times: “I began sifting the literature on saiga mortality and found strong hints of a possible cause in a study of smaller saiga die-offs in 2010 (12,000 animals) and 2011 (just 450) in the animal’s westernmost population, in the Urals. The paper has a ponderous title — “Examination of the forage basis of saiga in the Ural population on the background of the mass death in May 2010 and 2011.” The first thing that struck me was the similarity in timing. Those events and this year’s mass dying were in mid to late May.The reported symptoms in the dead and dying animals are the same, as well: foaming at the mouth, diarrhea and bloating. The paper on the Urals deaths also notes that well before the 2010 and 2011 events, there had been previous die-offs including in 1955, 1956, 1958, 1967, 1969, 1974, 1981 and 1988. [Source: Andrew C. Revkin, New York Times, May 29, 2015 ^^]

Til Dieterich, one of the authors of the paper on the Ural-region dyings, said: “As with an airplane crash, there is not only one cause behind this and it is not unprecedented…. In 1988 there was a mass death with 434,000 animals dead (68 percent of the population) more or less in the same region.” According to a paper by Dieterich and Bibigul Sarsenova: “Mass death of Saiga antelopes took place from 18 to 21 May 2010 in the north west of West Kazakhstan province northeast and southeast of Borsy (about 12, 000 dead animals found). In August and September the forage basis of Saiga antelope in the mass death area was investigated. ^^

“Mass growth of potentially poisonous Brassicacea species for ruminants could be found on abandoned fields in the area (Lepidium perfoliatum, Lepidium ruderale, Descurainia sophia and Thlaspi arvense). Due to favorable warm and wet weather conditions in spring 2010 the mass growth of these annual Brassicacea species occurred on a big scale. Even though Saiga is capable to eat large amount of this plants, they are poisonous to ruminants when consumed in large amounts. ^^

“In addition lush growth of Brassicacea and Poacea species (Poa bulbosa, Eremophyrum triticeum, Leymus ramosus, Elytrigia repens) providing high protein forage, can cause the observed symptoms of foamy fermentation, diarrhea and bloating. The animals thus could have been killed by extreme bloating and/or acute pulmonary edema (“fog fever”) after foraging on wet and highly nutritious “fog pastures.” Qualitative investigations in the field confirmed that the animals ate most above-mentioned species….In addition the animals have been congregating for calving, which does contribute to a higher background stress. The results of the investigation suggest that a combination of at least some of the above listed factors is responsible for the tragic events. ^^

“In both years the Saiga death events started just after the females and their 1–2 week old young started to move again. During the first 10 days of the calving time the females did not leave their young and not even move to the nearby water places for drinking. In both cases the calving sites where some meters higher and covered either by mainly steppe vegetation (2010, Stipa-Festuca Steppe) or Leymus ramosus grassland on fallow fields. Thus the moist pastures where presumably more intensively used during the death event. Nevertheless the heavy rain events just before or during the death event, did certainly lead to very moist fodder especially in the morning hours. In 2010 even fog was reported by the locals just before the dying started. The local people also reported, that Lepidium species do cause diarrhea in cattle and after heavy rain events herders do not let their livestock out to the pastures before noon. ^^

“Wet and warm weather conditions have also been reported for the Betbak Dala Population during the spring death events in 1981 and 1988. The animals have also been calving for the first time in the Borsy area usually using pastures further south in the semi desert region. Part of the Saiga population did actually calve further south in the semi-desert area 2011 and no deaths were reported here. Wet weather conditions in spring combined with lush pastures are thus obviously problematic to Saiga.

“The paper includes recommendations to limit risks of such events going forward: With this evidence on hand we recommend in similar wet years to keep Saiga off such dangerous pastures and train the responsible rangers in identifying the described dangerous conditions. If it turns out difficult or dangerous for the Saiga population to keep them off dangerous pastures, the relevant areas should just be cut during the time when the animals are immobile during the first 10 days of calving. Cutting the dangerous pastures will prevent excessive development of toxins and protein in the plants. Even if the plants are eaten dry the risk of negative effects is minimized. The authors warn against expanding agriculture in saiga territory, noting that plowing or herbicide use would simply lead to mass growth of the weedy toxic species in the cleared area...This will enlarge the risk of pasture problems even more.”

Cause of the Massive Saiga Antelope Die Off Figured Out

In April 2016, the Saiga Conservation Alliance announced that the massive die off of the saiga antelope was caused by a normally benign bacteria suddenly becoming deadly – although exactly how and why this happened is not known. Josh L Davis wrote in iflscience.com: After continued analysis of samples taken from the carcasses of the saiga, multiple laboratories have come to the same conclusion and identified the bacterium Pasteurella multocida as the cause. It is thought that the bacteria, which naturally lives in the respiratory tract of the animals and normally has no impact on their health somehow became deadly, leading to haemorrhagic septicaemia. The symptoms of the condition include a high fever, salivation, and shortness of breath, followed by death within 24 hours. This is consistent with what was observed in the field. [Source:Josh L Davis, iflscience.com, April 16, 2016 ~]

“It is not unknown for domestic animals to suffer from the same condition, but what is particularly unusual is the 100 percent mortality rate seen in the saiga herds. The reasons behind this are less clear, but could be related to earlier suggestions that unusual weather conditions may have been stressing the animals, many of which were mothers who had just given birth. ~

“As the Saiga Conservation Alliance says, the investigation into the animals’ deaths is still ongoing, with questions such as these still to clear up. With a next calving season creeping up, many biologists are waiting with baited breath to see what will occur. ~

Scientists say unseasonal rains triggered by climate change could played a part in the mass deaths of saiga. Al-Jazeera reported: “They say unusual weather — an exceptionally cold winter followed by a very wet spring — may have caused toxins produced by the Pasteurella bacteria to cause fatal internal bleeding in the animals organs. “"Climate may have had a role to play in this," Richard Kock, a professor at the Royal Veterinary College in London, told Al Jazeera. "This disease has been associated with domestic animals when there has been a storm or sudden drop of temperature," he added. “According to the researchers, female saigas and their calves were hit the hardest. Within hours of showing symptoms, which included diarrhoea and frothing at the mouth, the animals died. [Source: Al Jazeera, May 27, 2016]

Saiga Struck Again, By a Different Plague, in 2017

Erica Goode wrote in the New York Times: “They found the first carcasses in late December, on the frozen steppes of Mongolia’s western Khovd province. By the end of January, officials in the region had recorded the deaths of 2,500 saiga antelopes — about a quarter of the country’s saiga population — and scientists had identified a culprit: a virus called peste des petits ruminants, or P.P.R., also known as goat plague. It was the first time the disease, usually seen in goats, sheep and other small livestock, had been found in free-ranging antelopes. “It’s just one thing on top of another,” said Dr. Richard Kock, a professor of wildlife health and emerging diseases at the Royal Veterinary College in London who, with colleagues, concluded that climate change had contributed to the Kazakhstan die-off. “Once you’re down to very low numbers, a species is vulnerable to extinction,” Dr. Kock said. “You have to wake up to the fact that these populations really are on the brink, and you can’t do anything about it if it’s gone.” [Source: Erica Goode, New York Times, February 8, 2017]

“The appearance of P.P.R. in the antelope, which probably contracted the virus from close contact with livestock that graze on the steppe, raised fears that it could spread to other threatened species, like Bactrian camels and Mongolian gazelles. “Potentially, this could be an 80 percent mortality,” said Eleanor J. Milner-Gulland, a zoology professor at Oxford and chairwoman of the Saiga Conservation Alliance. “It could be completely disastrous.” Dr. Milner-Gulland noted that the spring, when the antelopes gather together to calve, could be an especially risky time for the spread of the virus, and there is concern that it could spread to antelopes remaining in Kazakhstan.

“Enkhtuvshin Shiilegdamba, an epidemiologist and the Wildlife Conservation Society’s country director in Mongolia, said that scientists believe the virus traveled to Mongolia from China, one of 76 countries around the world where P.P.R. is active. Livestock in Khovd province began to fall ill in September, Dr. Enkhtuvshin said. She added that the number of deaths so far was probably an underestimate, because the antelope are smallish animals and “this area is quite a large area and there is snow, so it makes it difficult to find them. “It’s likely that we already lost about 50 percent of the saiga population,” she added. Even before the virus hit, a fiercely harsh winter in 2015 had reduced the population to approximately 10,000 saigas from about 15,000. P.P.R. is also suspected in the deaths of 22 black-tailed gazelles and at least one ibex.

“Dr. Kock said that many of the dead antelope they examined were in poor physical condition, probably contributing to their susceptibility to disease. The die-off, he said, came at the worst time of year, during the winter, when the animals’ resistance is lower. “That is extremely bad luck and that will be reflected in the mortalities,” he said.

“About 11 million sheep and goats in Khovd and in a second province where saigas live were vaccinated against P.P.R. after the initial outbreak, but the vaccine was apparently not effective in preventing the virus from spreading to wildlife, suggesting that some animals were missed or that there were storage problems with the vaccines. The United Nations is running a progarm with the aim of eliminating P.P.R. by 2030.

Critically Endangered Saiga Comeback

The population of saiga more than doubled between 2019 and 2021 in Kazakhstan — 334,000 to 842,000. The BBC reported: “Following a series of conservation measures, including a government crackdown on poaching, and local and international conservation work, numbers have started to bounce back. That, together with the natural resilience of the species, gives hope for their future, said Albert Salemgareyev of the Association for the Conservation of Biodiversity of Kazakhstan (ACBK). "They give birth to twins every year, which gives high potential for the species to quickly recover," he told BBC News. [Source: Helen Briggs, BBC, July 4, 2021]

“The survey, carried out in April 2021, showed not only a big increase in the total numbers, but that one particular population in Ustyurt in the south of the country, has made a dramatic recovery. In 2015, there were barely more than 1,000 animals left in the area, but there's been a big increase to 12,000 in the 2021 census. The UK-based non-profit organisation, Fauna & Flora International, has been involved in efforts to protect the Ustyurt population by establishing a new anti-poaching ranger team and using satellite collaring to monitor saiga movements.

“David Gill, FFI senior programme manager for Central Asia, said the new census was the best evidence yet that decades of conservation efforts to protect the saiga were paying off. But he warned against complacency, saying saiga migrate across huge areas, so future development and infrastructure projects that might fragment its habitat remain a concern. "But this new data is cause for celebration," he added. "There are few truly vast wildernesses, like the steppes of central Asia, left on the planet. To know that saiga herds are still traversing them in their thousands, as they have done since prehistoric times, is an encouraging thought for those of us who want those wildernesses to remain."

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Animal Diversity Web animaldiversity.org ; National Geographic, Live Science, Natural History magazine, CNTO (China National Tourism Administration) David Attenborough books, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Discover magazine, The New Yorker, Time, BBC, CNN, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Wikipedia, The Guardian, Top Secret Animal Attack Files website and various books and other publications.

Last updated April 2025