PITCHER PLANTS

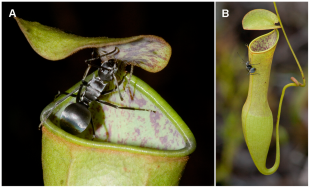

Pitcher plants are carnivorous plants that have a sack-like, toilet-shaped pitcher that has fluid inside that it used to catch insects. They often grow as climbing vines. The pitchers have entrapped ants, spiders, flies mosquitos, cockroaches, centipedes and even tadpoles, scorpions and mice. The plants consume insects and other creatures to get nitrogen which is often deficient in regions where they grow. Pitcher plants are not just hunters they are also prey. A number of animals feed on them despite their high acidity and powerful enzymes.

Pitcher plants (the genus Nepenthese) are found as far west as Madagascar, as far east as New Caledonia, as far south as northern Australia and as far north as coastal China. Many species can be found in southern Malaysia, Indonesia, China, Vietnam, Cambodia, the Philippines, and New Guinea. A few species are found in Madagascar, Australia. New Caledonia, India, Sri Lanka, and the Seychelles. Many of most interesting and spectacular species reside in peninsular Malaysia, the islands of Sumatra and Borneo. Their greatest diversity is found on Borneo where more than 50 species make their home. Altogether there are over 100 species of pitcher plant. Overseas, pitcher plants are coveted by collectors. There is a large profitable market to supply them. Some varieties sell for hundreds — even thousands — of dollars a piece.

According to Cambridge University: Pitcher plants are able colonize nutrient-poor habitats where other plants struggle to grow. Prey is captured in specialized pitcher-shaped leaves with slippery surfaces on the upper rim and inner wall, and drowns in the digestive fluid at the bottom. Under humid conditions, the wettable pitcher rim is covered by a very thin, continuous film of water. If an insect tries to walk on the wet surface, its adhesive pads (the 'soles' of its feet) are prevented from making contact with the surface and instead slip on the water layer, similar to the 'aquaplaning' effect of a car tire on a wet road. [Source: Cambridge University, June 14, 2012]

Pitcher plants range in sizes from 2.5 to 30 centimeters (one inch to one foot) and can carry anywhere from one teaspoon of water to over half a liter (a pint). A rare species in Brunei is the largest. As far as color is concerned, they range from bright red to pale green to almost black. According to Natural History magazine: it was assumed they were passive generalists that rely only on the most basic enticement — nectar — to capture hapless insects that stumble into their pitcher.” But in reality the plants “display a wide range of feeding strategies, some of which are exquisitely fine-tuned for trapping specific prey. [Source: Natural History magazine, October 2006]

RELATED ARTICLES:

TROPICAL RAINFORESTS: HISTORY, COMPONENTS, STRUCTURE, SOILS, WEATHER factsanddetails.com ;

BIODIVERSITY AND THE NUMBER OF SPECIES factsanddetails.com ;

RAINFOREST TREES, FRUITS, PLANTS AND BAMBOO factsanddetails.com ;

RAINFOREST LIANAS, FIGS, EPIPHYTES, FERNS, BROMELAIDS AND FUNGI factsanddetails.com ;

RAINFOREST ORCHIDS AND FLOWERS factsanddetails.com

Websites and Resources: Rainforest Action Network ran.org ; Rainforest Foundation rainforestfoundation.org ; World Rainforest Movement wrm.org.uy ; Wikipedia article Wikipedia ; Forest Peoples Programme forestpeoples.org ; Rainforest Alliance rainforest-alliance.org ; Nature Conservancy nature.org/rainforests ; National Geographic environment.nationalgeographic.com/environment/habitats/rainforest-profile ; Rainforest Photos rain-tree.com ; Rainforest Animals: Rainforest Animals rainforestanimals.net ; Mongabay.com mongabay.com ; Plants plants.usda.gov

Carnivorous Plants

Carnivorous plants are plants that get some or most of their nutrients from trapping and consuming animals — typically insects and other arthropods, and occasionally small mammals and birds — while getting all of their energy from photosynthesis. They typically occur in waterlogged sunny places where the soil is thin or poor in nutrients, especially nitrogen, such as acidic bogs. They can be found on all continents except Antarctica, and on many Pacific islands. In 1875, after years of painstaking research, Charles Darwin published the first treatise to recognize the significance of carnivory in plants — “Insectivorous Plants”. [Source: Wikipedia +]

There are roughly 750 plant species that in one way or another capture animals for food, with about three new species added to the list each year. Some such as sundews and butterworts use sticky flypaper on their leaves. Others, such as Venus fly traps and waterwheel plants have traps that spring shut. Bladderworts, which are primarily aquatic, suck in their victims with bladder-shaped vacuum traps.[Source: Natural History magazine, October 2006]

Many carnivorous plants have evolved their carnivorous methods independently. One thing they have in common is that are found in areas where there isn’t much nitrogen or other nutrients in the soils and they get these nutrients from their prey. True carnivory is believed to have evolved independently at least 12 times in five different orders of flowering plants,[ and is represented by more than a dozen genera.

Plants are considered carnivorous if they possess the following five traits: 1) capture prey in some kind of trap; 2) kill the prey; 3) digest the prey; 4) absorb nutrients from the digested prey; 5) use those nutrients to grow and develop. Other traits may include the attraction and retention of prey. +

Five basic trapping mechanisms are used by carnivorous plants: 1) Pitfall traps used by pitcher plants, in which prey is trapped in a rolled leaf containing a pool of digestive enzymes or bacteria; 2) Flypaper traps, which use a sticky mucilage; 3) Snap traps, which utilize rapid leaf movements; 4) Bladder traps, which suck in prey with a bladder that generates an internal vacuum; and 5) Lobster-pot traps, also known as eel traps, that have inward-pointing hairs to force prey to move towards a digestive organ. +

Pitcher Plant Growth

All pitcher plants have the same development pattern. First a seedling generates a number of pitchers on the ground. These urn-shaped terrestrial traps have two conspicuous leafy “wings” running the full length of the pitcher, from the tendril to the pitcher’s mouth. These are good for catching ants but not pollinators, As the plant grows the uppermost leaves bear a second line of more-elongated, wingless aerial pitchers that are more adept at catching flying insects, pollinators and beetles. [Source: Natural History magazine, October 2006]

The “pitcher” of a pitcher plant is not a flower like many believe but is actually a modified leaf shaped like a sack and topped by a wide hood. It forms at the end of a tendril that grows from the tip of a leaf.. The inside surface of the hood as well as the swollen lip that surrounds the opening of the pitcher are pocked with nectar glands that produce the fluids that attract insects. Rain fills the pitchers with water.

David Attenborough wrote in The Private Life of Plants, "The process of pitcher formation starts when the tip of a leaf begins to extend into a tendril. This gains support for itself by twisting around the stem of another plant, usually making no more than a single turn. Its lip begins to swell and to drop under its own weight. Then quite suddenly, it inflates with air. As it balloons larger and larger, flecks of color appear in its walls. Now it begins to fill with fluid, its growth is complete, and a lid-like segment at the top opens. The trap is now ready to receive visitors.” [Source: David Attenborough, The Private Life of Plants, Princeton University Press, 1995]

Pitcher Plants Catching Prey

Pitcher plant prey — usually small invertebrates — are attracted by the color of the pitcher and at least in some cases by fragrance. Lizards, perhaps in search of a drink, sometimes are drowned and digested. Scientists know this because the lizards leave behind two pairs of undigested miniature translucent eye covers.

Prey begins by feeding on nectar glands outside the pitcher but are eventually attracted by the larger nectar glands on the “more dangerous” peristome, or mouth of the pitcher. Depending on the species “the peristome may or may not provide firm footing. The unwitting visitor that loses its grip may become prey if it falls into the pitcher, landing in a pool of liquid secreted by the plant, Or the visitor may venture over the peristome and onto the inner well of the pitcher,” also often a fatal mistake.[Source: Natural History magazine, October 2006]

According to Natural History magazine: “In most Nepenthes species, the upper portion of the inner wall is covered with microscopic waxy scales, which cause the prey to slide into the liquid below. Once on the liquid the prey quickly becomes waterlogged, making flight or even crawling impossible. The only chance of escape is to bite through the pitcher wall, but few species have mouthparts with enough power to do that before they drown. The liquid — about acidic as Pepsi and full of enzymes that break down proteins — slowly digest the prey. Nitrogen-rich compounds that digestion releases from the prey carcass are absorbed by glands in the pitcher wall.”

Insects and Pitcher Plants

Pitcher plants lure prey to the "pitcher” with sweet-smelling nectar and fake flowers. Sometimes they even leave a trail for ants and other insects to follow to their doom. When the insect goes inside a pitcher to investigate it slips and falls into water inside the pitcher. Once inside the insect can't escape. Every time it tries to climb the pitcher walls it slip back down into the fluid at the boot of the pitcher, where it is sometimes stunned by chemicals. Eventually the insect drowns.

The inside of the pitcher is incredibly slippery. The upper part of the pitcher, below the nectar source on the underside of the pitcher’s lid, is covered by a slippery, waxy material that clings to the insect’s feet. Some pitcher plants have little bristles or downward-pointing hairs near the opening of the pitcher that acts like a fence to keep the insects in.

Many of the victims are flies and mosquitoes. Typically they land on the lid, and as they search for more nectar make their way over the edge slip on the walls. The waxy material of the walls breaks off as the insect tries to adhere to it and falls in the water. As the victim struggles it stimulates glands in the pitcher plant that excrete digestive acids..

Insects with a Symbiotic Relationship with Pitcher Plants

Living within the pitcher plants are a variety of insects that feed on the detritus in the fluid and in turn supply the plant with oxygen and nutrients derived from their bodily waste. These insects can break up large victims into small pieces that are easier to digest. Some pitcher plants are host to some large creatures. One species is home of half-inch-long crab.

There are some creatures that prey on pitcher plant prey. Crab spiders lived only in pitcher plant pitchers and intercept and devours pitcher plant prey. “Dangling from silken safety lines, the spider takes up station on the inner wall of the pitcher, waits for prey to enter, and then seizes it as it feds at the nectar glands. If disturbed the spider drops into the pitchers fluid and remains there until the threat has passed. Occasionally, they enter the fluid to fed on mosquito larvae.

Some moths and wasps are specially adapted to walk up and down the inside of the pitcher plant. Some deposit their eggs inside the pitcher (with the larvae feeding on the pitcher's prey) and help the plants reproduce by transporting pollen from plant to plant. Mosquito, gnat and fly larvae also live in the fluid, some of which battle each other over territory in the fluid. Some attract birds that are forced to feed on nectar in such a way that their excrement helps provide nutrients for the plant.

One species of ant, the schmitzi ant, is unaffected by the chemicals in the pitcher and is able to climb the walls and even rescuesof other insects. Describing rescue of a cockroach by these ants, Eric Hansen wrote in Discover magazine, “The rescue was slow and orderly. Once the diving schmitzi ants brought the cockroach to the edge of the reservoir, the other ants helped carry the wounded insect up the slippery vertical wall...The ants looked like a group of energetic six-legged rock climbers. With toenail-like crampons...the arduous two-inch ascent from fluid to resting place took more than an hour.” Once rescued the ants ripped the cockroach apart and ate it. Unconsumed bits were thrown back in the pitcher where they were consumed by mosquito larvae.

Pitcher Plant Digestion

The fluid inside a pitcher of a pitcher plant contains digestive acids and enzymes that break down the prey into nutrients that can be absorbed by the plant. Sometimes the prey slowly decomposes and survives for several days by eating the hollow interior of the pitcher. The acids and enzymes are produced by hundreds of digestive glands in the lower section of the pitcher.

The acids and enzymes eat at the soft part of insects and can even digest egg whites and meat. The exoskeletons of insects collect at the bottom of the pitcher like bones from uncollected battlefield corpses. Small insects can be digests in a few hors. A mice may take a week or more.

How does pitcher plant does digestion work? 1) Insects are trapped in the pitcher plant's fluid-filled trap. 2) The plant secretes digestive enzymes, such as proteases and chitinases, into the pitcher. 3) The enzymes break down the insect's soft parts. 4) The plant absorbs the nutrients from the digested prey. The time it takes for a pitcher plant to digest its prey can be several days or weeks. The length of time depends on the size of the prey and the type of plant.[Source: Google AI]

Species of Pitcher Plants

There are over 100 different species of pitcher plants. The shape of the pitcher varies in size and shape from species to species. Some resemble beer steins. Others look like toilets. A rare species found in Borneo is called the monkey scrotum plant because, well it looks like a monkey scrotum.

The world's largest pitcher plant, the “Nepenthes rajah”, or rajah pitcher, is found in Sabah in Borneo. It is the size of a football, hold up as much as two liters of fluid, and has been known to devour animals the size of a rat. The “Nepenthes northiana” is the largest lowland species. It is large enough to hold a liter of liquid and grab hold a child’s arm.

The fanged pitcher plant is so named because of a pair of thorn-like appendages that protrude form the bottom of the pitcher lid. The “Nepenthes veitchii” grows on wind-blown trees It is very colorful. Some have red-and-green or red-and white stripes. Other have bright yellow or red peristomes.

Some pitcher plants are very rare and endangered in part because they grow under very specialized conditions in a few specific areas, such as mountain tops in the Bornean rain forest. As was the case in the Victorian era, there is a strong demand from collectors for rare and beautiful species, which are sometimes smuggled from their native countries, in violation of international laws to collectors in the West and Japan.

Prey-Catching Strategies of Different Pitcher Plants

“The structural diversity of Nepenthese pitchers is matched by diversity of strategies for capturing nutrients. They range from relatively simple to outright bizarre.” At the simple end is N. Gracilis, found in lowland scrubs in Thailand, Malaysia and western Indonesia. It’s “traps are narrow place green, and only two to four inches long. They work by offering their prey the most basic enticement, sugary nectar. Ants are the most common prey; their affinity for nectar makes them easy targets. Beetles, flies and small wasps ate also frequent victims. [Source: Natural History magazine, October 2006]

N. Rafflesiana found in coastal Borneo has large pitchers that are boldly patterned in colors from yellow to scarlet and has a broad pitcher. “It reflects green and blue, and absorbs ultraviolet wavelengths, to which a large number of insects are visually sensitive. In addition the aerial pitchers give off a sweet fragrance attractive to many insects. Both kinds of lures, the visual and olfactory, are compelling example of convergent evolution: like flowers, pitchers lure insects via color, fragrance, and nectar, but the two structures evolved quite independently. As one might expect, the ariel pitchers of N. rafflesiana trap pollinating insects, including bees, beetles and moths. Both aerial and terrestrial pitchers trap ants.

The N. lowii is pitcher plant species that lives in the highlands of several mountains in Borneo. “It bears distinctive pitchers, eight to ten inches high, each with a flaring, funnel-shaped mouth, a narrow waist, and a large lid that secretes copious quantities of a crystalline, sugary substance. The pitchers rarely catch insects but are filled with feces from animals such as treeshrews or small squirrels that feed o invertebrates and sweet fruits.

The pitcher of the N. Albomarginata has a cream-colored band just below the pitcher’s rim that mimics a kind of lichen that a species of termites likes to eat. Many of these termites fall into the pitcher as prey. Several dozen species of invertebrates, including mites and the larvae of hoverflies, midges and mosquitoes, have been found in the pitchers of N. bicalcarata. These plants also have a symbiotic relationship with a species of ant that live inside the swollen hollow base of the pitchers which also thorn-like nectar glands. The ants can swim and periodically they swim in the pitcher’s liquid and extract large prey and consume them. Scientists believe the ants help the plants by preventing “bacteria overload” if the plant contains too much prey.

Pitcher Plant That Uses Rain Drops to Capture Prey

In June 2012, in a paper published in the journal PLoS ONE, researchers at Cambridge University announced that they had discover novel trapping mechanism in Nepenthes gracilis pitchers. During heavy rain, the lid of these plants acts like a springboard, catapulting insects that seek shelter on its underside directly into the fluid-filled pitcher. [Source: Cambridge University, June 14, 2012]

The lead author of the paper, Dr Ulrike Bauer from the University of Cambridge’s Department of Plant Sciences, said: “It all started with the observation of a beetle seeking shelter under a N. gracilis lid during a tropical rainstorm. Instead of finding a safe — and dry — place to rest, the beetle ended up in the pitcher fluid, captured by the plant. We had observed ants crawling under the lid without difficulty many times before, so we assumed that the rain played a role, maybe causing the lid to vibrate and 'catapulting' the beetle into the trap, similar to the springboard at a swimming pool.”

According to a Cambridge University news release: To test their hypothesis, the scientists simulated 'rain' with a hospital drip and recorded its effect on a captive colony of ants that was foraging on the nectar under the lid. They counted the number of ants that fell from the lid in relation to the total number of visitors. They found that ants were safe before and directly after the 'rain', but when the drip was switched on about 40 percent of the ants got trapped.

Further research revealed that the lower lid surface of the N. gracilis pitcher is covered with highly specialised wax crystals. This structure seems to provide just the right level of slipperiness to enable insects to walk on the surface under 'calm' conditions but lose their footing when the lid is disturbed (in most cases, by rain drops). The scientists also found that the lid of N. gracilis secretes larger amounts of attractive nectar than that of other pitcher plants, presumably to take advantage of this unique mechanism.

Water, Cooked Rice and Hair Gel from Pitcher Plants

Pitcher plants are sometimes called monkey cups because it is believed that monkeys drink from them. Scientist Paul Zahl, who wrote an article for National Geographic about the plants, didn't see any monkeys in the wild drinking from them but he did offer a pitcher plant to an orangutan who grabbed it out of his hand and chugged the water down in a single gulp. Zahl also tried water inside another pitcher plant and said it was cooler than the water in his canteen. He also tried the water inside a pitcher plant which he said was good but warm. He carefully selected pitchers that didn't have any dead insects inside.

While climbing Mount Ophir on Peninsula Malaysia in the summer of 1854, the naturalist Alfred Russel Wallace occasionally drank from pitcher plants. He wrote: The height, as measured by a sympiesometer, was about 2,800 feet. We had been told we should find water at Padang-batu as we were exceedingly thirsty; but we looked about for it in vain. At last we turned to the pitcher-plants, but the water contained in the pitchers (about half a pint in each) was full of insects, and otherwise uninviting. On tasting it, however, we found it very palatable though rather warm, and we all quenched our thirst from these natural jugs.

Villagers in Brunei use the water from pitcher plants in styling gels and hair conditioner. In other places the fluid is used as a burn ointment and a skin moisturizer and a treatment for eye inflamation. Most people who are in contact with the plant wince at the idea because the plant’s smell bad and the fluid contains too many insects and biting ants. Melanesian Islanders thought that pitcher plant contents smell like rat urine.

In Brunei, some people believe that the fluids from young pitcher plants has hair-restorative properties. One scientist who tried it said it didn’t work. The pitchers themselves are used like rice cookers for the preparation of certain dishes. Though the exact method varies from place to place, the basic idea is the same: Stuffing a washed pitcher with rice, steaming it or placing it on hot ashes. When ready, the rice is eaten and the pitcher is discarded.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Animal Diversity Web animaldiversity.org ; National Geographic, Live Science, Natural History magazine, David Attenborough books, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Discover magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Wikipedia, The Guardian, Top Secret Animal Attack Files website and various books and other publications.

Last updated February 2025