EARLY HISTORY OF BUDDHISM

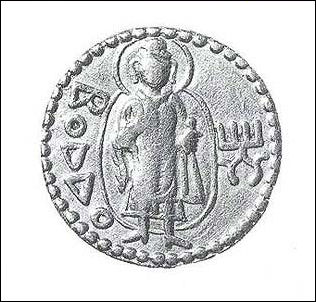

Kushan coin from 100 BC,

earliest surviving Buddha image Buddhism originated in what are now north India and Nepal during the sixth century B.C. Buddhism began as a reaction to Hindu doctrines and as an effort to reform them. Nevertheless, the two faiths share many basic assumptions. Both view the universe and all life therein as parts of a cycle of eternal flux. In each religion, the present life of an individual is a phase in an endless chain of events. Life and death are merely alternate aspects of individual existence marked by the transition points of birth and death. An individual is thus continually reborn, perhaps in human form, perhaps in some non-human form, depending upon his or her actions in the previous life. The endless cycle of rebirth is known as samsara (wheel of life). [Library of Congress ]

Buddhism is a tolerant, non prescriptive religion that does not require belief in a supreme being. Its precepts require that each individual take full responsibility for his own actions and omissions. Buddhism is based on three concepts: dharma (the doctrine of the Buddha, his guide to right actions and belief); karma (the belief that one's life now and in future lives depends upon one's own deeds and misdeeds and that as an individual one is responsible for, and rewarded on the basis of, the sum total of one's acts and omissions in all one's incarnations past and present); and sangha, the ascetic community within which man can improve his karma.*

The Buddha added the hope of escape —a way to get out of the endless cycle of pain and sorrow — to the Brahmanic idea of samsara. The Buddhist salvation is nirvana, a final extinction of one's self. Nirvana may be attained by achieving good karma through earning much merit and avoiding misdeeds. A Buddhist's pilgrimage through existence is a constant attempt to distance himself or herself from the world and finally to achieve complete detachment, or nirvana. *

See Separate Article 1) ANCIENT INDIA IN THE TIME OF THE BUDDHA factsanddetails.com 2) EARLY HISTORY OF BUDDHISM IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; 3) LATER HISTORY OF BUDDHISM IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; and 4) SILK ROAD AND THE SPREAD OF BUDDHISM factsanddetails.com

Websites and Resources on Buddhism: Buddha Net buddhanet.net/e-learning/basic-guide ; Wikipedia article Wikipedia ; Internet Sacred Texts Archive sacred-texts.com/bud/index ; Introduction to Buddhism webspace.ship.edu/cgboer/buddhaintro ; Early Buddhist texts, translations, and parallels, SuttaCentral suttacentral.net ; East Asian Buddhist Studies: A Reference Guide, UCLA web.archive.org ; View on Buddhism viewonbuddhism.org ; Tricycle: The Buddhist Review tricycle.org ; BBC - Religion: Buddhism bbc.co.uk/religion ; A sketch of the Buddha's Life accesstoinsight.org ; What Was The Buddha Like? by Ven S. Dhammika buddhanet.net ; Jataka Tales (Stories About Buddha) sacred-texts.com ; Illustrated Jataka Tales and Buddhist stories ignca.nic.in/jatak ; Buddhist Tales buddhanet.net ; Arahants, Buddhas and Bodhisattvas by Bhikkhu Bodhi accesstoinsight.org

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Buddhism: Its Essence and Development” by Edward Conze Amazon.com ;

“An Introduction to Buddhism: Teachings, History and Practices” by Peter Harvey Amazon.com ;

“The Art of Buddhism: An Introduction to Its History and Meaning Paperback”

by Denise Patry Leid Amazon.com ;

“The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Buddhism” (500 Photographs) by Ian Harris Amazon.com ;

“Buddhist Scriptures” by Donald Lopez (Penguin Classics) Amazon.com ;

“What the Buddha Taught” by Walpola Rahula Amazon.com ;

“In the Buddha's Words: Anthology of Discourses from the Pali Canon” with Bhikkhu Bodhi, the Dalai Lama Amazon.com ;

“The Heart of the Buddha's Teaching” by Thich Nhat Hanh Amazon.com ;

“Buddhism” by Madhu Bazaz Wangu (1993 Amazon.com ;

“Buddhism Plain and Simple”

by Steve Hagen Amazon.com ;

“Little Buddha” (Film) Amazon.com

“The Life of the Buddha: According to the Pali Canon” by ven Bhikkhu Ñanamoli Amazon.com ;

The Buddha and the Founding of Buddhism

Great Sanchi stupa, the world's oldest Buddhist structure, dating back to the 3rd century BC

Buddhism was founded by a Sakya prince, Siddhartha Gautama (563-483 B.C.; his traditional dates are 623-543 B.C., also called the Gautama Buddha), who, at the age of twenty-nine, after witnessing old age, sickness, death, and meditation, renounced his high status and left his wife and infant son for a life of asceticism. After years of seeking truth, he is said to have attained enlightenment while sitting alone under a bo tree. He became the Buddha — "the enlightened" — and formed an order of monks, the sangha, and later an order of nuns. He spent the remainder of his life as a wandering preacher, dying at the age of eighty.

The early history of Buddhism is bound up with the life of its founder In his First Sermon to his followers — which many say marks the formal beginning of Buddhism — the Buddha described a moral code, the dharma, which the sangha was to teach after him.

Siddhartha Gautama is believed by scholars to have been an actual historical figure. is generally accepted. He was born into a noble family in present-day Lumbini, modern Nepal. His father, Suddhodana, ruled over a small fiefdom and was part of the ruling Sakya clan. Nearly all that is known about the Buddha comes from accounts written centuries after he died. In 1996, however, a team of archaeologists discovered a marker honoring the Buddha's birthplace set the by the emperor Ashoka in 250 B.C.

Development of Buddhism after Buddha's Death

The Buddha left no designated successor after his death. It is difficult to reconstruct exactly how Buddhism was created after Buddha's death, the same way it is difficult to say exactly how Christianity evolved after the death of Jesus. For centuries after his death, Buddha's disciples and followers orally passed down facts and legends about Buddha’s life, dialogues, sayings, deeds and teachings and these were in turn passed down from generation to generation.

Towards the end of his life, the Buddha instructed his followers that no individual or group could hold authority over the community of monks and laypeople. Instead, authority was to be shared by all. This created an egalitarian religious community. This may have been nice in theory but in practice as it opened the way for productive debate about the meaning and significance of his teachings after the Buddha's death, but it also opened the way for disagreement and schisms.[Source: Jacob Kinnard, Worldmark Encyclopedia of Religious Practices, 2018, Encyclopedia.com]

During the centuries following The Buddha's death, Buddhism evolved into an institutional religion. Monastic orders were formed and worship of the relics of the Buddha, and the Buddha himself, became popular. According to tradition, the first Buddhist texts were collected a few weeks after the Buddha’s death, when 500 arhants gathered at Rajagaha for what was effectively the First Council of the Buddhist faith. During the period that followed there a great deal of scholarly debate on philosophical and religious issues, many of which were not addressed or purposely avoided by the Buddha. This debate resulted in the schism of Theravada and Mahayana Buddhism.

The teachings of the Buddha were recorded by his students and then codified. About four centuries passed between the time of Buddha’s death and when his Sayings, Utterances and Discourses were written down. One of the main reasons for this is that there were no materials used for writing or even engraving in India until that time. . The Buddha's sermons are regarded by scholars as as largely authentic.

Buddha never claimed to be anything more than a human being who had found a path to truth and enlightenment. By the 1st century B.C. he had essentially been deified. Power struggles took place in Buddhism while The Buddha alive and after his death. His scheming cousin Devadetta tried to rest leadership from him. There were also many power struggles, divisions and rebellions among monks after his death.

Early Buddhists are thought to have practiced their faith by making visits to places the Buddha had been or see relics such as teeth or bones. Perhaps because he put so much emphasis on self-denial no images were made him for some time and when they were made they were not true likenesses.

In the early era of Buddhism there were three primary paths for the devotee. He or she could become 1) an “arahat”, a worthy person who has achieved the goal of a Buddhist life by gaining insight into the true nature of things: 2) a “paccekabuddha”, one who reaches enlightenment by living alone as an “isolated Buddha”; and 3) a fully awakened Buddha

Arhats (Buddha's Disciples)

Arhats (Buddha's Disciples) were key figures in the early days of Buddhism after the Buddha's death. According to tradition, the Buddha's first sermon was so powerful that his first five disciples attained enlightenment after only one week, becoming arhats (worthy ones). These five followers then began to teach the dharma that the Buddha had shared with them, marking the beginning of the Buddhist sangha, the community and institution of monks central to the religion. The Buddha's immediate disciples were also responsible for orally preserving his teachings.

The first five ascetics who became the first monks under The Buddha were joined by 55 others. They together with The Buddha are known as the 61 arhats. The were ordained by The Buddha by repeating the simple phrase: “Come monk; well-taught in the Dharma; fare the attainment of knowledge for making a complete anguish.” Others that came later were ordained after cutting their hair and beard, donning a robe and uttering three times: “I go to The Buddha for refuge, I go to Dharma for refuge, I go to the sangha for refuge.” This ritual remains the basis of the Theravada monk ordination process today.

Ananda was The Buddha's constant companion. The Buddha's cousin, he accompanied the Buddha for more than 20 years and appears in many early Buddhist texts. His two chief disciples — Sariputta (Sariputra) and Maudgalyayana (Moggallana, Maha moggallana) — were two ascetics who for were known for seeking the Dharma to deathlessness. They were the Buddha's first converts. Sariputta was the Buddha's most trusted disciple and was often depicted as the wisest. Sariputta. He served as the Buddha's son's teacher when he joined the community of monks. [Source: Jacob Kinnard, Worldmark Encyclopedia of Religious Practices, 2018, Encyclopedia.com]

Mahakassapa,was ranked the highest for his ability to interpret the Buddha’s brief statements. Aa Brahman who became a close disciple of the Buddha, he presided over the first Buddhist council at Rajagriha (modern Rajgir, in Bihar) and was later celebrated in Ch'an (Zen in Japan) as the recipient of the Buddha's special, esoteric teachings. When asked a question about the Dharma, the Buddha is said to have held up a flower and Mahakassapa smiled, silently signifying his reception of this special teaching.

Buddhism Gains a Following

relief of "foreigners" visiting the Sanchi Supa from the stupa's Northern Gateway

Buddhism really got going after the Indian emperor Asoka (273-232 B.C.) patronized the sangha and encouraged the teaching of the Buddha's philosophy throughout his vast empire. By 246 B.C., the new religion had reached Sri Lanka. The Tripitaka, the collection of basic Buddhist texts, was written down for the first time in Sri Lanka during a major Buddhist conference in the second or first century B.C. Emperor Asoka who embraced Buddhism after he heard and understood the Buddha’s dharma. held the Third Buddhist Council. Maha Thera Ashim Moggalana Putta Tisa presided over the Council. At his advice. the Council with the royal patronage and support of Asoka sent out religious missions to nine places and nine countries to spread the Dharma. Buddha’s Teachings. [Source: Library of Congress *]

As Buddhism grew after the Buddha's death, various ritual practices developed. Despite differences among Buddhist traditions regarding their view of the Buddha, he remained a venerated figure for all Buddhists. Devotees gave gifts to relics associated with the Buddha and celebrated his birth, enlightenment, and entrance into nirvana annually. Sites associated with the Buddha's life became places of pilgrimage. The Buddha's birthplace was Lumbinì, while he achieved enlightenment in Bodh Gaya. His first sermon was delivered in Deer Park, and he passed away in Kuśinagara. From the common era onwards, artists began creating images of the Buddha. Additionally, Buddhist monastic communities (sangha) were quickly established after the Buddha's death, with ordination ceremonies for both monks and nuns signifying their renunciation of worldly pursuits. Laypeople also started to admire monks for their spiritual achievements and often gave them gifts and offerings. Additionally, Buddhist funeral and protective rituals were developed.[Source: Joseph W. Williams, International Encyclopedia of the Social Sciences, 2000s, Encyclopedia.com]

Buddhism arrived in most places as a foreign religion. Rather than attempting to make inroads by condemning existing religions it took a more diplomatic approach and borrowed elements of the existing religions and was gradually absorbed. Tibetan Buddhism for example, incorporated elements of the local shamanistic bon religion. Ironically, Buddhism has all but died in its birthplace in India.

According to the Venerable Pang Khat, Theravada Buddhism reached Southeast Asia as early as the second or third century A.D., while Mahayana Buddhism did not arrive in Cambodia until about A.D. 791. In Southeast Asia, Mahayana Buddhism carried many Brahman beliefs with it to the royal courts of Funan, of Champa, and of other states. At this time, Sanskrit words were added to the Khmer and to the Cham languages. Theravada Buddhism (with its scriptures in the Pali language), remained influential in Sri Lanka, and by the thirteenth century it had spread into Burma, Thailand, Laos, and Cambodia, where it supplanted Mahayana Buddhism. *

Reasons Buddhism Took Hold

In its first two and half centuries, Buddhism struggled to gain traction and many sects arose and sectarian disputes broke out between them. But still Buddhism attracted followers. Like Christianity, it was embraced by many people early in its history because of its promises of salvation and an afterlife. In its early days Buddhism was often practiced in conjunction with Hinduism and local animist beliefs and people said prayers to Buddha and their gods, and this was not considered a contradiction. Another appeal of Buddhism is that like Christianity it was open to everyone: men and women, members of all castes, clans and families. Members of other religions and sects were welcomed.

Gregory Smits wrote that “Buddhism arose in response to the problem of human suffering. More specifically, if we are all destined to become ill, grow old, and die, what is the point of life? Of course, this is the basic issue with which most religions grapple...After trying various approaches, the original Buddha came up with a core insight that life is infused with suffering because of our insatiable desires. As a result, we should strove to eliminate our desires, which will eliminate the suffering. This proposition may sound reasonable and simple, but putting it into practice is terribly difficult.” [Source: “Topics in Japanese Cultural History” by Gregory Smits, Penn State University figal-sensei.org ~]

Buddha's death

“Recall that enlightenment cannot be described in words. Although the Buddha himself had become enlightened, not even he was able to enlighten others. All he could do was set them in the right direction. The personal charisma of the Buddha after he became enlightened attracted followers. After his death, however, these followers did not always agree on their master's teachings. A few months after the Buddha died, his disciples assembled the First Buddhist Council. The purpose of this assembly was to establish a formal canon, true to the Buddha's teachings. ~

“Buddhism developed within the context of other religious and metaphysical ideas, one of which was reincarnation. Early Buddhists took for granted that we are reborn endlessly, and the quest to put an end to suffering was functionally equivalent to the quest to end the cycle of birth, death, and rebirth. Death, in other words, is not the end, but not in the sense of a soul traveling to some mysterious afterlife beyond earth. Instead, our deaths are just preludes to more births here on earth (as a human or some other creature). The trials, tribulations, sufferings, joys, and accomplishments of a lifetime never last.” ~

Steven M. Kossak and Edith W. Watts of the Metropolitan Museum of Art wrote: “Buddhism attracted many people for whom caste and the Brahmins’ exclusive control over worship were problematic. Even before the Buddha’s death, many of his followers had become monks and nuns and were settling into monasteries provided by wealthy laity as merit-producing gifts. Gradually the monks spread his teachings across northern India in peaceful conversions. The main focus of worship became stupas, hemispherical mounds containing relics of the Buddha or other transcendent beings and often decorated with scenes from the Jatakas (folk tales about the past lives of the Buddha). The faithful also made pilgrimages to important places in the Buddha’s life, including his birthplace, the bodhi tree at Bodh Gaya where he reached enlightenment, and the Deer Park at Sarnath where he preached his first sermon. As the centuries passed, pilgrims throughout Asia came to visit these sacred sites. There they learned about the Buddha’s life and his teachings.” [Source: Steven M. Kossak and Edith W. Watts, The Art of South, and Southeast Asia, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York]

World's Oldest Buddhist Shrine — Dating to the Buddha’s Time — Found in Nepal

In November 2013, AFP reported: “The discovery of a previously unknown wooden structure at the place of the Buddha’s birth suggests the sage might have lived in the 6th century B.C. — two centuries earlier than thought — archeologists said. Traces of what appears to have been an ancient timber shrine were found under a brick temple that is itself within Buddhism’s sacred Maya Devi Temple at Lumbini, southern Nepal, near the Indian border. In design it resembles the Asokan temple erected on top of it. Significantly, however, it features an open area, unprotected from the elements, from which it seems a tree once grew — possibly the tree under which the Buddha was born. “This sheds light on a very very long debate” over when the Buddha was born and, in turn, when the faith that grew out of his teachings took root, archaeologist Robin Coningham said. [Source: AFP-Jiji, November 26, 2013]

It’s widely accepted that the Buddha was born beneath a hardwood sal tree at Lumbini as his mother, Queen Maya Devi, the wife of a clan chief, was traveling to her father’s kingdom to give birth. But much of what is known about his life and time has its origins in oral tradition — with little scientific evidence to sort out fact from myth. Many scholars contend that the Buddha — who renounced material wealth to embrace and preach a life of enlightenment — lived and taught in the 4th century B.C., dying at around the age of 80. “What our work has demonstrated is that we have this shrine (at Buddha’s birthplace) established in the 6th century B.C.” that supports the hypothesis that the Buddha might have lived and taught in that earlier era, Coningham said.

ruins within Maya Devi Temple Complez

Radiocarbon and optically stimulated luminescence techniques were used to date fragments of charcoal and grains of sand found at the site. Geoarchaeological research meanwhile confirmed the existence of tree roots within the temple’s central open area. The team’s peer-reviewed findings appear in the December issue of the journal Antiquity, ahead of the 17th congress of the International Association of Buddhist Studies in Vienna in August next year.

Lumbini was overgrown by jungle before its rediscovery in 1896. Since it’s a working temple, the archeologists found themselves digging in the midst of meditating monks, nuns and pilgrims. It’s not unusual in history for adherents of one faith to have built a place of worship atop the ruins of a venue connected with another religion. But what makes Lumbini special, Coningham said, is how the design of the wooden shrine resembles that of the multiple structures built over it over time. Equally significant is what the archaeologists did not find: signs of any dramatic change in which the site has been used over the ages. “This is one of those rare occasions when belief, tradition, archaeology and science actually come together,” he said.

Development of Buddhist Canon

Buddha appears to have written little or nothing himself. The earliest Buddhist writing that we have today date back to a period 150 years after Buddha's death. Early Buddhist literature consisted mostly of records of sermons and conversations involving The Buddha that were recorded in Sanskrit or the ancient Pali language.

The Buddha's teachings were initially preserved orally by his followers who had heard his discourses. With no named successor upon his death, a council of elders formed to perpetuate his teachings. Centuries later, these teachings were codified in Buddhist scriptures, which included material directly attributed to the Buddha (buddhavacana) and authoritative commentaries. The Tripitaka canon, also known as the Pali canon or Tipitaka, is the earliest extant canon. It includes 1) the Vinaya (monastic law or discipline), 2) the Dharma (Doctrine), or Sutras (the Buddha's discourses), and Abhidhamma (Abhidharma , commentaries or Advanced Doctrine)). [Source: Joseph W. Williams, International Encyclopedia of the Social Sciences, 2000s, Encyclopedia.com]

As the monks formed these collections, they debated the content and significance of the discourses. New situations arose that were not explicitly addressed by the Buddha, leading to the need for new rules and resulting in further disagreements.The Chinese and Tibetan canons were developed later and contain additional material. [Source: Jacob Kinnard, Worldmark Encyclopedia of Religious Practices, 2018, Encyclopedia.com]

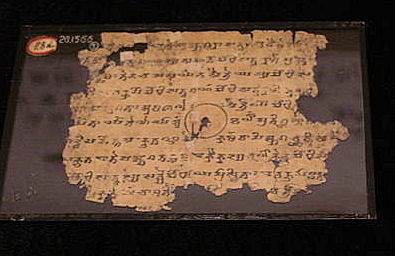

5th century Lotus Sutra fragment According to tradition, the first texts were collected between the Council of Rajaharha, which took place after Buddha’s cremation, and the first Buddhist schism in the 4th century B.C. These texts consist primarily of orthodox doctrines and discourses and rules recited by the highly respected monks Ananda and Upali. They became the “Vinaya Piataka” and the “Sutra Pitaka”.

Concerns about different interpretations of Buddha’s teachings emerged early. The main goal of the council at Rajagaha was to recite out loud the Dharma (Buddha’s teachings) and the “Vinaya” (a code of conduct for monks) and come to some agreement on what were the true teachings and what should be preserved, studied and followed. Their guiding belief was that “Dharma is well taught by the Bhagavan (“the Blessed One”)” and that it is self-realized “immediately,” and is a “a come-and-see thing” and it leads “the doer of it to the complete destruction of anguish.”

The Vinaya-Pijtaka (the rules for monastic life) was developed at the First Council from a question and answer session between the Upali and the Elder Kassapa. The Sutra-Pijtaka (“Teaching Basket”) is a collection of teachings and sayings from Buddha, often called the “sutras” . It came about from the dialogue between young Anada an the Elder Kassapa about Dharma. A third basket, the “Abhidhamma Pitaka” (Metaphysical Basket) was also produced. It contains detailed descriptions of Buddhist doctrines and philosophy. Its origin is disputed. Together these made up the “Tipitaki” (Three Baskets of Wisdom), the foundation of Buddhism, and sometimes called the “Pali Cannon” because it was originally written in the ancient Pali language.

Development of Buddhist Schools

Without Buddha or an authoritative hierarchy around to settle disputes or divergences of a opinion different groups with different viewpoints were formed. Within two or three centuries after Buddha’s death 18 major schools or sects had appeared. Some of them became associated with specific monastic centers and places.

The debates over doctrines, texts and interpretations of what the Buddha said often led to disputes and schisms within the Buddhist community. After the Buddha's death, the First Council was held in Rajagriha (present-day Rajgir, in Bihar) to discuss issues of doctrine and practice. About a century after the First Council was held a Second Council was held at Vesali to deal with a rebellious minority that refused to accept the decisions of the orthodox majority.

Due to disagreements over proper practice and doctrine voiced at these councils, the sangha eventually divided into two different lines of monastic ordination: the Sthavira (Elders) and the Mahasanghika (Great Assembly). Initially, their differences mostly revolved around issues of monastic discipline, or Vinaya. The Mahasanghikas were rebels. They rejected certain positions in the Pali Canon and saw The Buddha as a kind of mysterious figure who only appeared in earth in a phantom-body. Their beliefs influenced the Trikaya (three bodies) doctrine of the Mahayana school.

The Sthavira and Mahasanghika groups evolved into the Theravada and Mahayana, respectively. They developed different doctrinal and ritual standards and became established in different parts of Asia. Periodically other Theravada Council have been held with the aim of “purifying” the record of what Buddha originally said. The sixth was held in Rangoon in 1956.[Source: Jacob Kinnard, Worldmark Encyclopedia of Religious Practices, 2018, Encyclopedia.com]

By the time of the Second Council, conference, a schism had developed separating Mahayana (Greater Path) Buddhism from more conservative Theravada (Way of the Elders, or Hinayana — Lesser Path) faction or Buddhism. The Theravada School focused on the personal pursuit of enlightenment. The Mahayana believed in helping everyone to achieve enlightenment. This central difference was a big part of the two groups split. The Mahayana faction reinterpreted the original teachings of the Buddha and added a type of deity called a bodhisattva to large numbers of other buddhas. The Mahayana adherents believe that nirvana is available to everyone, not just to select holy men. Mahayana Buddhism quickly spread throughout India, China, Korea, Japan, Central Asia, and to some parts of Southeast Asia. [Source: Library of Congress]

See Separate Article DEVELOPMENT OF MAHAYANA BUDDHISM AND THERAVADA BUDDHISM factsanddetails.com

First Buddhist Council

Sattapanni or Sattaparni Cave, on one of the hills around Rajgir, Bihar, India, is where the First Buddhist Council took place, in the year after the Buddha's passsing away (Parinirvana)

Several weeks or months after the Buddha’s death his closest disciples convened the First Council in Rajagaha (present-day Rajgir, in Bihar, India). According to traditional sources there were disputes over the early Buddhist doctrine and the council was called to fix authoritive versions of the sayings of the Buddha, the Vinaya (law) and the Dharma (doctrine and teachings).

Dr. W. Rahula wrote: Maha Kassapa, the most respected and elderly monk, presided over that council. Two very important Great Disciples (mahatheras) who specialized in the two distinct areas of the Teaching (the Dharma and the Vinaya) were present. The first was Ananda, the Buddha’s closest companion and disciple over the preceding 25 years. Endowed with a remarkable memory (even in an age of remarkable memories), Ananda was able to recite all the discourses the Buddha had uttered. [When sutras begin “Thus have I heard,” Ananda is that “I” and he made this statement in front of the First Council of enlightened elders]. The other monastic was Upali, who had committed all of the Discipline to memory. The other personality was Upali who remembered all the Vinaya rules.[Source: Dr. W. Rahula, BuddhaSasana (budsas.org), Wisdom Quarterly: American Buddhist Journal, August 14, 2008; Grant Olson, Center for Southeast Asian Studies at Northern Illinois University +++]

“Only these two sections, Discourses and Discipline, were recited at the First Council. Although there were no differences of opinion on the Dharma (no mention was yet made of the Abhidharma, “Higher Teaching,” the metaphysical and psychological explanations), there was some discussion about the Rules. Before the Buddha’s was to pass into nirvana, he told Ananda that if the Order wished to amend or modify some “minor” rules after his passing, they could do so. But on that occasion Ananda, overpowered by grief on hearing of the Buddha’s impending passing, it did not occur to him to ask what the “minor” rules were. +++

“As the members of the First Council were unable to agree as to what constituted those minor rules, Maha Kassapa finally ruled that no disciplinary rule laid down by the Buddha should be changed and that no new ones should be introduced. No intrinsic reason was given. Maha Kassapa did say one thing, however: “If we changed the rules, people would say that Ven. Gautama’s disciples changed them even before his funeral pyre had gone out.” At the First Council, the Dharma was divided into various sections, and each section was assigned to an Elder (a Thera) and his pupils to commit to memory. The Dharma (or “Teaching,” the Vada) was then passed on from teacher to pupil orally. The Dharma was recited daily by groups of monastics who often cross checked each other to ensure that no omissions or additions were made. Historians agree that an oral tradition is more reliable than a report written by one person from memory several years later.” +++

Second Buddhist Council and the Theravada-Mahayana Split

A Second Buddhist Council was convened in roughly 334 B.C. was held at Vesali (present-day Vaishali, or Vaiśālī in Bihar, India, to deal in another effort to unify Buddhist teachings and settle ten questions concerning monastic discipline, Ultimately though it led to the first major schism in Buddhism. According to “Topics in Japanese Cultural History”: “The participants in this council also compiled a biography of the Buddha. Soon after the Second Council, the Buddhist community split up over disagreements regarding issues of doctrine, canonical texts, and monastic discipline — the specifics of which need not concern us here. [Source: “Topics in Japanese Cultural History” by Gregory Smits, Penn State University figal-sensei.org ~]

1st century BC depiction from the Sanchi Stupa abd 5th century BC Kushinagar, the place where Buddha died

“At this time, Buddhism split into two major varieties: Mahayana and Theravada. Theravada means "Teaching of the Elders," and, at least according to the claims of Theravadins, remained closest to the teachings of the original Buddha. Theravada Buddhism stressed liberation of the individual by retracing the steps Shakyamuni had walked. Geographically, Theravada spread to southern India and across the sea to Southeast Asia. Today, it thrives in places such as Sri Lanka, Burma, and Thailand. Because Theravada Buddhism had little influence on East Asia, we do not deal with it in this course.” ~

Sanskrit scholar R.P. Hayes wrote: “The Sangha (the monastic community) split over the political question of 'Who runs the Sangha?' A controversy over some monastic rules was decided by a committee of Arahats (fully Enlightened monks or nuns) against the views of the majority of monks. The disgruntled majority resented what they saw as the excessive influence of the small number of Arahats in monastery affairs. From then on, over a period of several decades, the disaffected majority partially succeeded in lowering the exalted status of the Arahat and raising in its place the ideal of the Bodhisattva (an unenlightened being training to be a Buddha). Previously unknown scriptures, supposedly spoken by the Buddha and hidden in the dragon world, then appeared giving a philosophical justification for the superiority of the Bodhisattva over the allegedly 'selfish' Arahat. This group of monks and nuns were first known as the 'Maha Sangha', meaning 'the great (part) of the monastic community'. Later, after impressive development, they called themselves the 'Mahayana', the 'Greater Vehicle' while quite disparagingly calling the older Theravada 'Hinayana', the 'Inferior Vehicle'. [Source: R.P. Hayes, Buddhist Society of Western Australia, Buddha Sasana]

Important Buddhist Theologians

Nargarjuna (A.D. c. 150 – c. 250 CE) is regarded by many as the second greatest teacher in Buddhism. Some people even feel that Nagarjuna is the second Buddha who The Buddha prophesied would come sometime after to clarify things. Nagarjuna did much to clarify the nature of emptiness and is responsible for the Heart Sutra. Nagarjuna is widely considered the most important Mahayana philosopher. Along with his disciple Aryadeva, he founded the Madhyamaka (Middle Way) school of Mahayana Buddhism. Nagarjuna is counted as a patriarch of both Zen and Vajrayana (Tibetan Buddhism). He is held in the highest regard by all branches of the Mahayana. Nagarjuna is also credited with developing the philosophy of the Prajñaparamita sutras and, in some sources, with having revealed these scriptures in the world, having recovered them from the nagas (water spirits often depicted in the form of serpent-like humans). Furthermore, he is traditionally supposed to have written several treatises on rasayana as well as serving a term as the head of Nalanda. [Source: Wikipedia +]

See Nagarjuna Under HISTORY OF MAHAYANA BUDDHISM factsanddetails.com

Kumarajiva (A.D. 344–413), a Buddhist scholar and missionary, is another important early author was who had a profound influence in China as a translator and a clarifier of Buddhist terminology and philosophy. [Source: Jacob Kinnard, Worldmark Encyclopedia of Religious Practices, 2018, Encyclopedia.com]

Buddhaghosa — who lived in the A.D. fifth century— was one of the greatest Buddhist scholars in the religion's history. He translated Sinhalese commentaries into Pali, wrote numerous commentaries himself, and composed the Visuddhimagga (later translated as Path of Purification by Bhikkhu Ñanamoli).

Asanga (310–90) and Vasubandhu (420–500) are the founders of the Yogacara (Consciousness-Only) school of Mahayan Buddhism. Vasubandhu was an Indian philosopher. His Abhidharmakosa is one of the fullest expositions of the Abhidharma teachings of the Theravada school. The Yogacara School proposed that all phenomena originate in the mind through eight kinds of awareness that reveal the illusion that there is an objective world and cause all humans to acquire the wisdom whereby they unite with the ultimate. Asanga developed the system in a form that greatly influenced China and Japan. For him the essence of things consists in the oneness of the totality of things; ignorance of the totality results in the illusory phenomenal world. [Source: A. S. Rosso,; Jones, C. B. New Catholic Encyclopedia, Encyclopedia.com]

Dhammapala — lived in the sixth to seventh century — was the author of numerous commentaries on the Pali canon and stands as one of the most influential figures in the Theravada.

Shantideva — lived in the seventh to eighth century — s a later representative of the Madhyamika school of Mahayana Buddhism and author of two important surviving works, the Shikshasamuccaya (Compendium of Doctrines) and Bodhisattva Avatara (Entering the Path of Enlightenment), the latter of which is still used in Tibetan Buddhism as a teaching text.

Decline of Buddhism

Buddhism is virtually non existent in India, today. Only about five million people out of a population of over 1 billion people practice the religion and most of them are untouchables or residents of the southern state of Maharashtra or Himalayan states like Ladakh. Buddhism died out in India partly because the religion was centered in monasteries that where way out of reach of lay people, and monks didn’t beget other monks. Among the other factors that hastened its demise was the influence of Islam, the loss of royal patronage, the similarities between Buddhism and Hinduism and the loss of distinctiveness.

The Gupta Empire (A.D. 320 to 647) was marked by the return of Hinduism as the state religion in India and Buddhism declined there. The Gupta era is regarded as the classical period of Hindu art, literature and science. After Buddhism died out Hinduism returned in the form of a religion called Brahmanism (named after the caste of Hindu priests). Vedic traditions were combined with the worship of a multitude of indigenous gods (seen as manifestations of Vedic gods). Buddhism all but disappeared from India by the A.D. 6th century.

Under the influence of Hinduism the Mahayana school evolved a pantheon of Buddhas and Bodhisattvas and a metaphysics of a pantheistic world soul complicated by Yoga and Tantra practices. Arising as a variation of Hinduism, this sort of Buddhism was naturally reabsorbed by it, for Hinduism, which had deeper and stronger roots in the Indian soul, in time developed a caste system with impassable social and religious barriers. This was incompatible with classless Buddhism.

Peter A. Pardue wrote in the International Encyclopedia of the Social Sciences:After the tenth century A.D. Buddhism began a perceptible decline, for reasons which are still far from clear. The Mahayana philosophical schools became increasingly preoccupied with abstruse theoretical issues and hairsplitting polemics. In time theistic Mahayana and Tantric Buddhism became hardly distinguishable from the increasingly luxuriant garden of Hinduism. [Source: Peter A. Pardue, International Encyclopedia of the Social Sciences, 2000s, Encyclopedia.com]

The great medieval Hindu philosopher Shankara successfully incorporated the strong points of Buddhist philosophy in a decisive synthesis. Buddhist monasteries, schools, and cults began to lose their popular foundation, and we can see the slow but sure absorption of its symbolism, intellectual leadership, and laity into the richness of what étienne Lamotte has called I’hindouisme ambiant. The Buddha was represented as one among many incarnations of the Hindu god Visnu.

Last Gasps of Buddhism in India

In the 11th century Buddhism was still strong in Kashmir, Orissa, and Bihar. In 2021, the ruins of a unique 11th- or 12th-century Buddhist monastery were unearthed at the site of Lal Pahari in Bihar State. According to Archaeology magazine: While there are other monasteries in the region, this is the only one built on a remote hilltop, where residents could practice their religion in peace. It was also unusual because its leader was a woman. Unlike other known monasteries, the cells at Lal Pahari had doors, a measure of privacy that implies that the monastery housed either an all-female or mixed-gender population. [Source: Archaeology magazine, March 2021]

Around the same time, archaeologists in the eastern Indian state of Jharkhand have unearthed a small vihara, an early type of Buddhist monastery. A team from the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI) investigating several mounds in a hilly area found a Buddhist shrine in one of them and the vihara in another. According to Rajendra Dehuri, ASI deputy superintending archaeologist, the monastery includes six rooms that open onto a wide veranda. Also found at the site were sculptures of Gautama Buddha, as well as the Buddhist deities Avalokiteshvara and Tara. The structure appears to have been built between the eighth and eleventh centuries A.D. [Source: Gurvinder SINGH, Archaeology Magazine, July/August 2021

With the establishment of the Muslim power in 1193, Buddhism disappeared from Northern India, where it originated. In Western India it vanished at about the mid 12th century under the rising tide of Hinduism. Internal and external causes account for the decay of Buddhism in India. Although Buddha taught salvation through personal effort without dependence on any god, he neither denied the existence of the Hindu gods nor forbade their worship or the rites connected with birth, marriage, and death. While Buddhism is now widespread in other parts of Asia, it is only followed by about 0.7 percent of the population of modern India, according to a 2011 census. [Sources: Live Science, A. S. Rosso,; Jones, C. B. New Catholic Encyclopedia, Encyclopedia.com]

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, Brooklyn College, Onmark Productions

Text Sources: East Asia History Sourcebook sourcebooks.fordham.edu , “Topics in Japanese Cultural History” by Gregory Smits, Penn State University figal-sensei.org, Asia for Educators, Columbia University; Asia Society Museum “The Essence of Buddhism” Edited by E. Haldeman-Julius, 1922, Project Gutenberg, Virtual Library Sri Lanka; “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “Encyclopedia of the World's Religions” edited by R.C. Zaehner (Barnes & Noble Books, 1959); “Encyclopedia of the World Cultures: Volume 5 East and Southeast Asia” edited by Paul Hockings (G.K. Hall & Company, New York, 1993); BBC, Wikipedia, National Geographic, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, The New Yorker, Reuters, AP, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides and various books and other publications.

Last updated March 2024