BUDDHIST TEXTS

The TipitakaNo single canon, or collection, of scripture is accepted by all Buddhist sects. The primary text for nearly all schools of Buddhism is the Tipitaka, also called the Pali Canon (See Below).

Another popular Buddhist text is the Dhammapada, a collection of the Buddha's sayings. Early texts were made primarily for monks. The “Pali Tripitaka” is among the oldest texts. Different regions produced their own canons. Buddhist words and names have two forms: one in Sanskrit and one in Pali.

A lot of Buddhist dogma is handled with stories and fables rather than metaphysical pondering. The earliest doctrines were laid out in relatively easy to understand parables and anecdotes. Scholars believe that many of the miracles, myths and legends attributed to Buddha were created after his death "to convey the lofty intellectual ideas of Buddhism in a more understandable format" to poor uneducated people. Buddha himself was not big on ideology or dogma. His teachings were practical ways for people to gain the same insights he found by delving into themselves.

Writing, printing, reciting, chanting and reading Buddhist scriptures are thought of simple, easy ways for Buddhists to earn merit and create a better position for themselves in the afterlife. Many monks spend a good portion of their time printing Buddhist texts and hanging the paper on trees to dry. Often, the monks don't know what the prints say. Families sometimes place printed texts over their door of their homes keep thieves and demons away.

The 9th century Buddhist master Lin Chi said, “If you meet the Buddha on the road, kill him” — the point being that making a master teacher into an idol misses the essence of his teaching. The "Gospel of Buddha" is a 19th century compilation from a variety of Buddhist texts by Paul Carus. It is modelled on the New Testament as was very widely read. It was even recommended by Sri Lankaese Buddhist leaders as a teaching tool for Buddhist children.

Websites and Resources on Buddhism: Buddha Net buddhanet.net/e-learning/basic-guide ; Wikipedia article Wikipedia ; Internet Sacred Texts Archive sacred-texts.com/bud/index ; Introduction to Buddhism webspace.ship.edu/cgboer/buddhaintro ; Early Buddhist texts, translations, and parallels, SuttaCentral suttacentral.net ; East Asian Buddhist Studies: A Reference Guide, UCLA web.archive.org ; View on Buddhism viewonbuddhism.org ; Tricycle: The Buddhist Review tricycle.org ; BBC - Religion: Buddhism bbc.co.uk/religion ; A sketch of the Buddha's Life accesstoinsight.org ; What Was The Buddha Like? by Ven S. Dhammika buddhanet.net ; Jataka Tales (Stories About Buddha) sacred-texts.com ; Illustrated Jataka Tales and Buddhist stories ignca.nic.in/jatak ; Buddhist Tales buddhanet.net ; Arahants, Buddhas and Bodhisattvas by Bhikkhu Bodhi accesstoinsight.org

Theravada Buddhism: Readings in Theravada Buddhism, Access to Insight accesstoinsight.org/ ;

Wikipedia article Wikipedia ;

Encyclopædia Britannica britannica.com ;

Pali Canon Online palicanon.org ;

Vipassanā (Theravada Buddhist Meditation) Wikipedia article Wikipedia ;

Pali Canon - Access to Insight accesstoinsight.org ;

Forest monk tradition abhayagiri.org/about/thai-forest-tradition ;

BBC Theravada Buddhism bbc.co.uk/religion;

Mahayana Buddhism: Seon Zen Buddhism buddhism.org ; Readings in Zen Buddhism, Hakuin Ekaku (Ed: Monika Bincsik) terebess.hu/zen/hakuin ; How to do Zazen (Zen Buddhist Meditation) global.sotozen-net.or.jp ;

Wikipedia article Wikipedia ;

Comparison of Buddhist Traditions (Mahayana – Therevada – Tibetan) studybuddhism.com ;

The Mahayana Mahaparinirvana Sutra: complete text and analysis nirvanasutra.net ;

Buddhas and Bodhisattvas in Mahayana Buddhism cttbusa.org ;

; Zen Buddhism zen-buddhism.net ;

The Zen Site thezensite.com ;

Wikipedia article on Zen Buddhism Wikipedia

Tibetan Buddhism: ; Religion Facts religionfacts.com ; Wikipedia article Wikipedia ; Tibetan Buddhist archives sacred-texts.com ; Buddha.net list of Tibetan Buddhism sources buddhanet.net ; Tibetan Buddhist Meditation tricycle.org/magazine/tibetan-buddhist-meditation ; Gray, David B. (Apr 2016). "Tantra and the Tantric Traditions of Hinduism and Buddhism". Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Religion. oxfordre.com/religion ; Wikipedia article on Tibetan Buddhism Wikipedia ; Shambhala.com. largest publisher of Tibetan Buddhist Books shambhala.com ; tbrc.org ; Tibetan Philosophy, Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy iep.utm.edu/tibetan

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Buddhist Scriptures” by Donald Lopez (Penguin Classics) Amazon.com ;

“What the Buddha Taught” by Walpola Rahula Amazon.com ;

“In the Buddha's Words: Anthology of Discourses from the Pali Canon” with Bhikkhu Bodhi, the Dalai Lama Amazon.com ;

“The Heart of the Buddha's Teaching” by Thich Nhat Hanh Amazon.com ;

“The Heart Sutra: A Comprehensive Guide to the Classic of Mahayana Buddhism”

by Kazuaki Tanahashi Amazon.com ;

“The Lotus Sutra: A Contemporary Translation of a Buddhist Classic”by Gene Reeves Amazon.com ;

“The Dhammapada” (Easwaran's Classics of Indian Spirituality) Amazon.com ;

“Twenty Jataka Tales” (Illustrated) by Noor Inayat Khan H. Willebeek Le Mair Amazon.com ;

“Jataka Tales” (audiobook) narrated by Ellen Burstyn

Amazon.com ;

“Buddha Stories” by Demi (1997) Amazon.com

Main Buddhist Texts

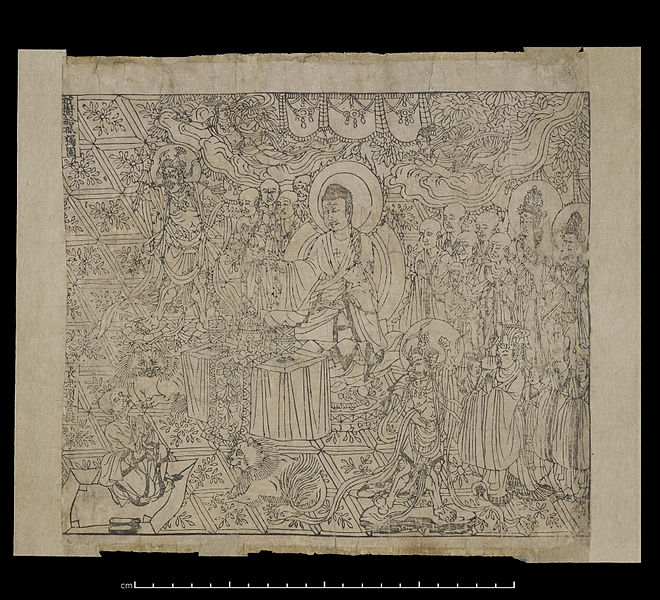

5th century fragment of the Lotus Sutra

The primary text for all schools of Buddhism is the Tipitaka (Three Baskets of Wisdom), also called the Pali Canon. It contains rules for monastic living, teachings of the Buddha, and explanations of philosophical questions (See Below). The earliest systematic and most complete collection of early Buddhist sacred literature, it is also called the “Pali Cannon” because it was originally written in the ancient Pali language. Forming the canon for the Theravada sect, it is 16,000 pages long and contains in 53 volumes. The texts that exist today have has mainly been compiled British scholars over the past century. One scholar who helped compile them told AFP, "After the whole 16,000 pages, you'd probably be too old to write down your conclusions.”

The “Dhammapada” is a collection of more sayings from Buddha within the Tipitaka. Other commentaries and Buddhist literary pieces are called “sutras” . Sayings attributed to The Buddha are also called “sutras” . “The Jatakas” is a group of stories that tell of Buddha's rebirths in the form of Bodhisattvas and animals, with each story embodying lesson from Buddha's teachings.

Theravada Buddhists tend to stick to the texts mentioned above while Mahayana Buddhists and Tibetan Buddhists have their sutras and texts, which Theravada Buddhists don’t acknowledge, that number in the thousands.

Another important text for Buddhists, primariliy Mahayana Buddhists, the Mulamadhyamaka-Karika, written around A.D. 150 by the Indian monk Nagarjuna. It contains and thorough discussion of the Madhyamaka, or "the Middle Way, and the system of thought it describes. The term "middle way" is often used to describe Buddhism as a whole. It illustrates the Buddha's belief, as discussed by Nagarjuna, that one must avoid extremes in order to achieve enlightenment, including extreme severity or harshness and extreme leniency or ease. [Source: Encyclopedia.com]

Tipitaka (Pali Canon)

The Tipitaka, also known as the Pali Canon or Tripitaka, is the earliest extant canon. More than 2,500 years old, it covers a period of two millennia, if the lives of past Buddhas are included, and comprises: 1) the Sutta Pitaka (monastic law or discipline); 2) the Vinaya Pitaka, with the Dharma (Doctrine), or Sutras (the Buddha's discourses); and 3) Abhidhamma (Abhidharma , commentaries or Advanced Doctrine).

The Sutta Pitaka (also referred to as the teachings of the Buddha) is comprised of 30 or so volumes of the Buddha's discourses as well as various instructional and ritual texts. It contains 227 rules for monks and 311 rules for nuns that advise them on how to handle themselves in certain situations and describes the relationships between the Sangha (monk community) and lay people. The 227 rules for monks is called the Patimokkha. It also details how and why the rules were developed.

The Vinaya Pitaka embraces the whole of Buddhist philosophy and ethics and includes the Dhammapada which contains the essence of Buddha's teaching. The Vinaya Pitaka recounts the teachings of the Buddha. It contains more than ten thousand sutras, or teachings, including instructions on conduct and meditation. The Dhammapada is mainly a collection of the Buddha's sayings and teachings, and is referred to often by Buddhists of all schools. The Vinaya also contains narratives of the Buddha's life, rules for rituals, instructions for ordination, and an extensive index of topics covered.

The Abhidamma Pitaka contains supplementary philosophy, religious teaching and instructions on how to seek wisdom and self-knowledge. Three are also songs, poems, and stories from the Buddha's past lives. The scholastic teachings are highly abstract, philosophical texts dealing with all sorts of topics, especially the minutiae that make up human experience. It runs for around 6,000 pages. [Source: Jacob Kinnard, Worldmark Encyclopedia of Religious Practices, 2018, Encyclopedia.com]

The Tipitaka contains approximately four million words and have remained virtually unaltered since they were written down. In addition to the basic texts of the Tipitaka, each text is accompanied by an extensive commentary and often several sub-commentaries that clarify the grammatical and linguistic ambiguities of the text, expand the analysis, and serve as a kind of reader's (or listener's) guide through the sometimes confusing philosophical and ritual points of the book.[Source: Jacob Kinnard, Worldmark Encyclopedia of Religious Practices, 2018, Encyclopedia.com]

The teachings of the Tipitaka were determined during the First Buddhist Council, held shortly after the Buddha's death. They were passed down orally for more than one hundred years before first being written down around the third century B.C. and were revised after that. Because many of the scriptures are elaborations of the Buddha’s original brief statements by his disciples the Tipitaka is more of a collection of elaborations, explanations and expansions of Buddha’s First Utterance or Discourse. Over the centuries, Buddhists scholars have reshaped these texts as Christians have with the Bible. In “The End of Suffering: The Buddha in the World”, journalist Pankaj Mishra wrote that Buddha’s dialogues were often “long-winded and repetitious” with “little of the artistry so evident in Plato.”

See Theravada Buddhist Texts Below

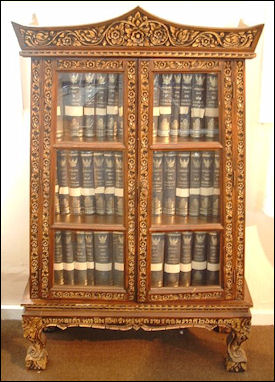

Burmese Pali manuscript

Putting Together the Early Buddhist Cannon

The Buddha appears to have written little or nothing himself. But he did famously tell his main disciple, Ananda, that after his death the Dharma he left behind would continue to be the present teacher, the "guiding light," for all future Buddhists,The earliest Buddhist writing that we have today date back to a period 150 years after Buddha's death. Early Buddhist literature consisted mostly of records of sermons and conversations involving The Buddha that were recorded in Sanskrit or the ancient Pali language.

Tradition holds that during the first rainy season retreat after the Buddha's death, sometime in the second half of the sixth century B.C., the Buddha's disciples gathered at Rajagriha (modern Rajgir, in Bihar) and began orally collected all of the Buddha's teachings into three sets or "three baskets" (tripitaka; Pali, tipitaka). These three collections form the basis of the Buddhist canon. According to the BBC: Although these texts are accepted as definitive scriptures, non-Buddhists should understand that they do not contain divine revelations or absolute truths that followers accept as a matter of faith. They are tools that the individual tries to use in their own life.

The first texts were collected between the Council of Rajaharha and the first Buddhist schism in the 4th century B.C. These texts consist primarily of orthodox doctrines and discourses and rules recited by the highly respected monks Ananda and Upali. They became the “Vinaya Piataka” and the “Sutra Pitaka”. These were collected into their final form around the 3rd century BCE, after a Buddhist council at Patna in India. Around the end of the first century A.D., these oral texts were written down. [Source: Jacob Kinnard, Worldmark Encyclopedia of Religious Practices, 2018, Encyclopedia.com, BBC]

Development of Buddhist Cannon

Concerns about different interpretations of Buddha’s teachings emerged early. The main goal of the council at Rajagaha was to recite out loud the Dharma (Buddha’s teachings) and the “Vinaya” (a code of conduct for monks) and come to some agreement on what were the true teachings and what should be preserved, studied and followed. Their guiding belief was that “Dharma is well taught by the Bhagavan (“the Blessed One”)” and that it is self-realized “immediately,” and is a “a come-and-see thing” and it leads “the doer of it to the complete destruction of anguish.”

The Buddha's teachings were initially preserved orally by his followers who had heard his discourses. With no named successor upon his death, a council of elders formed to perpetuate his teachings. Centuries later, these teachings were codified in Buddhist scriptures, which included material directly attributed to the Buddha (buddhavacana) and authoritative commentaries. [Source: Joseph W. Williams, International Encyclopedia of the Social Sciences, 2000s, Encyclopedia.com]

The Vinaya-Pijtaka (the rules for monastic life) was developed at the First Council from a question and answer session between the Upali and the Elder Kassapa. The Sutra-Pijtaka (“Teaching Basket”) is a collection of teachings and sayings from Buddha, often called the “sutras” . It came about from the dialogue between young Anada an the Elder Kassapa about Dharma. A third basket, the “Abhidhamma Pitaka” (Metaphysical Basket) was also produced. It contains detailed descriptions of Buddhist doctrines and philosophy. Its origin is disputed. Together these made up the “Tipitaki” (Three Baskets of Wisdom), the foundation of Buddhism, and sometimes called the “Pali Cannon” because it was originally written in the ancient Pali language.

Tipitaka scripture

As the monks formed these collections, they debated the content and significance of the discourses. New situations arose that were not explicitly addressed by the Buddha, leading to the need for new rules and resulting in further disagreements.The Chinese and Tibetan canons were developed later and contain additional material. [Source: Jacob Kinnard, Worldmark Encyclopedia of Religious Practices, 2018, Encyclopedia.com]

With the rise of the Mahayana, new books were added to this basic canonical core, most of them composed in Sanskrit; however, tradition holds that these were not new sacred texts, but the higher teachings of the Buddha himself, set aside for later revelation. Perhaps the best known of these is the Lotus Sutra, probably composed around the turn of the first millennium, as well as the Prajnaparamita (Perfection of Wisdom) texts. Additional texts were added as the Mahayana schools developed in India. As Buddhism branched out, these texts and the earlier Tipitaka were translated by Buddhist monks from both Tibet and China. These translations sometimes led to further expansion of the canon, especially in Tibet, where the rise of the Vajrayana (Tantric) schools led to more new texts; likewise, as Ch'an (Zen in Japan) developed, new sacred texts were written and preserved. [Source: Jacob Kinnard, Worldmark Encyclopedia of Religious Practices, 2018, Encyclopedia.com]

Jatakas

Jataka means "Birth Story" or "related to a birth". The Jataka tales comprise a sizable body of literature native to the Indian subcontinent which mainly concern the previous births of Gautama Buddha in both human and animal form. Jataka stories can be seen in temple paintings, cave art the railings and torans of the stupas. According to Peter Skilling, this genre is "one of the oldest classes of Buddhist literature." Some of these works are also considered great works of literature in their own right. [Source: Wikipedia]

In these fable-like stories, the future Buddha appears as a king, an outcast, a deva, an animal — but, in whatever form, he exhibits some virtue that the tale illustrates. Often there is an extensive cast of characters who get into various scrapes and are rescued by the Buddha character, resulting in a happy ending. The Jataka genre is based on the idea that the Buddha was able to recollect all his past lives and thus could use these memories to tell a story and illustrate his teachings.

In the teaching of Buddhism, the jatakas illustrate the many lives, acts and spiritual practices which are required on the long path to Buddhahood.[ They also illustrate the great qualities or perfections of the Buddha (such as generosity) and teach Buddhist moral lessons, particularly within the framework of karma and rebirth. Jataka stories have also been illustrated in Buddhist architecture throughout the Buddhist world and they continue to be an important element in popular Buddhist art. Some of the earliest such illustrations can be found at Sanchi and Bharhut.

The Jataka tales are quite ancient. Depictions of them appear in Indian art as early as the 2nd century B.C. and they are widely represented in ancient Indian inscriptions. According to Naomi Appleton, Jataka collections also may have played "an important role in the formation and communication of ideas about buddhahood, karma and merit, and the place of the Buddha in relation to other buddhas and bodhisattvas." Jatakas are closely related to (and often overlap with) another genre of Buddhist narrative, the avadana, which is a story of any karmically significant deed often by a bodhisattva and its result.

Texts for Different Buddhist Sects

Theravada Buddhism's main scripture is the Tipitaka. The Dhammapada — Sayings of Buddha — is popular: It is part of the Tipitaka. [Source: Buddhism Depot]

Mahayana Main scriptures embrace 2,184 sutras (sacred texts). Among the most popular ones are: 1) Lotus Sutra — a sermon by the Buddha on Bodhisattvas and buddha-nature; 2) Perfection of Wisdom Sutra (Prajna-paramita) — describes emptiness and other conditions; 3) Heart Sutra— describes nirvana, emptiness, and Ultimate Reality; and 4) "Land of Bliss" Sutra — describes the Pure Land of Amitabha Buddha.

Vajrayana: Tantric texts and commentaries deal mainly with Ultimate Reality as singular Unity, and the sexual union of world (male) and cosmos (female). The most well-known texts are: 1) Great Stages of Enlightenment — which deals with ethical behavior and control of mind; and 2) Tibetan Book of the Dead — which deals with stages of dying, death, and rebirth.

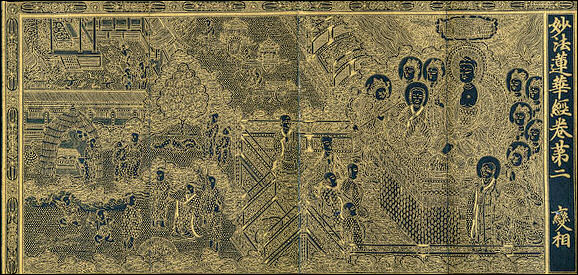

Goryeo-Illustrated manuscript of the Lotus Sutra, 1340

Theravada Buddhist Texts

Theravada Buddhism uses the Tipitaka (Pali Canon) as its official sacred text (See Above). It is comprised of three parts. 1) The first basket is the “Vinaya Piataka” (“Discipline Basket”). This text is made up of simple rules prescribed for people who wish to become devote Buddhists or monks. 2) The second part, the “Sutra Pitaka” (“Teaching Basket”), is comprised of teachings and sayings of Buddha. 3) The third part, The “Abhidhamma Pitaka” (“Metaphysical Basket”) has detailed descriptions of Buddhist doctrines and philosophy. Theravada Buddhist monks consider it important to learn sections of these texts by heart. [Source: BBC]

Theravada Buddhist teachings were written down in Sri Lanka during the A.D. 1st century. They were written in Pali (a language like Sanskrit).The Tipitaka, is a collection of Pali language texts. It forms the doctrinal foundation of Theravada Buddhism, and is the main body of scriptures all Buddhists. Tipitaka is translated as "three" (Ti) "baskets" (pitaka), in the Pali language. The three baskets are: 1) the Basket of (monastic) Discipline; 2) the Basket of Discourses; 3) the Basket of Further Dhamma. They coincide with the three parts of Tipitaka describe above

See Separate Article: THERAVADA BUDDHIST TEXTS factsanddetails.com

Mahayana Buddhist Texts

Mahayana Buddhism developed and revealed more than two thousand new texts and sutras in addition to the Tipitaka. Mahayana sutras are usually statements attributed to The Buddha centuries after he supposedly said them but are true enough to Buddhist doctrines that they have been accepted as truths among Mahayana Buddhists.

Most of the Mahayana canon is in the form of Sutras, Sastras and Tantras. Sutra (sutta) means discourse.. Sutras are the most authoritative and widely accepted as doctrine. Sutras are often chanted in prayers and written or printed again and again to earn merit. Sastras are much less universally accepted and are usually associated with a particular school. They are often commentaries attributed by name to a person with a specific school. Tantras are secret documents linked with the esoteric Tantric sects that are only supposed to be viewed by those who have been properly initiated.

According to Mahayana tradition, many of these were kept secret and released only when people were ready to hear them. Many were written between 200 B.C. and A.D. 200. Most Mahayana literature is in Sanskrit, and some is in Chinese, Tibetan and Central Asian languages. The most widely used sutras are The Lotus Sutra and sutras from The Perfection of Wisdom, of which there are about 30 different version put together over about a 700 year period.

See Separate Article: MAHAYANA BUDDHIST TEXTS factsanddetails.com

Duahang Diamond sutra from China

Lotus Sutra and Other Important Mahayana Sutras

The Lotus Sutra (The Lotus of the Good Law Sutra or Suddharma-Pundarika Sutra ("White Lotus of True Dharma")) is the most popular Mahayana text. It contains discussions on the importance of becoming a bodhisattva and realizing one's essential Buddha-nature. The Buddha-nature is present in every person and allows them to grow and gain greater understanding. [Source: Encyclopedia.com]

The Lotus Sutra, is one of the most widely venerated and beautiful Buddhist scriptures. Followers often believe that salvation can be achieved by repeatedly chanting, "I take my refuge in the Lotus Sutra" and passages from the Lotus sutra in front of a small altar containing a scroll with Chinese characters representing the Lotus Sutra. Translations of it into English or other Western languages are not very good. A 40-year-old Japanese housewife told Time she wakes up at dawn, places rice and water on the family altar and chants the same passages from the Lotus sutra over and over for around 25 minutes while kneeling and clasping her hands together around prayer beads. After she makes breakfast and gets her husband and children out the door she spends another 45 minutes chanting. "I feel so good afterwards," she said, refreshed and ready for the day."

Another important Mahayana text is the Prajnaparamita or "Perfection of Wisdom" Sutras, which includes the "Heart Sutra" or "Diamond Sutra". Only a few pages long, the Diamond Sutra contains some of the basic principles of Mahayana Buddhism, including its view of emptiness, nirvana, human nature, and reality. Different Mahayana sub-schools use different sutras as their central texts. These include the Pure Land Sutra, in which the Buddha describes to his disciple Ananda the heaven called the Pure Land and how to be reborn there; the Mumon-kan (Gateless Gate), which contains the best-known Zen koan collections; and the Tibetan Book of the Dead, which informs Vajrayana Buddhists about the spiritual opportunities available immediately after death. [Source: Encyclopedia.com]

Wood Block Printing and the World’s Oldest Book

Buddhist monasteries were instrumental in the development of the world’s first block printing in China in the A.D. 7th century. Buddhists believe that a person can earn merit by duplicating images of Buddha and sacred Buddhist texts. The more images and texts one makes the more merit one earns. Small wooden stamps — the most primitive form of printing — as well as rubbings from stones, seals, and stencils were used to make images over and over. In this way printing developed because it was "the easiest, most efficient and most cost effective way" to earn merit. The world's oldest surviving book, the Diamond Sutra, was printed in China in A.D. 868. It consists of Buddhist scriptures printed on 2½-foot-long, one-foot-wide sheets of paper pasted together on one 16-foot-long scroll. Because virtually all original Indian scriptures have been lost Chinese translations of Indian scriptures have been invaluable in trying to figure out what the original Indian texts said.

Text Sources: East Asia History Sourcebook sourcebooks.fordham.edu , “Topics in Japanese Cultural History” by Gregory Smits, Penn State University figal-sensei.org, Asia for Educators, Columbia University; Asia Society Museum “The Essence of Buddhism” Edited by E. Haldeman-Julius, 1922, Project Gutenberg, Virtual Library Sri Lanka; “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “Encyclopedia of the World's Religions” edited by R.C. Zaehner (Barnes & Noble Books, 1959); “Encyclopedia of the World Cultures: Volume 5 East and Southeast Asia” edited by Paul Hockings (G.K. Hall & Company, New York, 1993); BBC, Wikipedia, National Geographic, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, The New Yorker, Reuters, AP, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides and various books and other publications.

Last updated March 2024