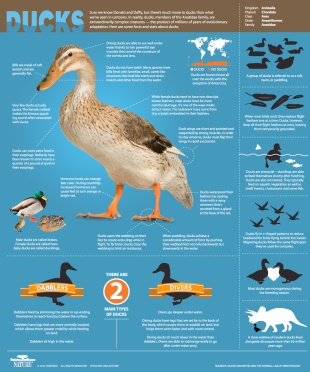

DUCKS

There are more than 100 species of duck worldwide. They are among the most successful bird species, doing well in urban areas and the rural countryside as well as well as wilderness ones, with some groups of ducks having hundreds of thousands of members. Technically a duck is a male. Females are called drakes. Young are called ducklings. A group of ducks is sometimes called a “paddling of ducks.”

There are over 150 species of waterfowl, including ducks, swans and geese. They typically have webbing between their front three toes for swimming and wide, flat bills with fine serrations on the sides. Most are ground nesters. Chicks are covered with a dense coat of soft, fluffy feathers known as down. Adult birds have soft down underneath their feathers for insulation and waterproofing. This down is used as filling for sleeping bags and down coats.

Many northern hemisphere species of waterfowl breed in the marshes, lakes and tundra of Alaska, Canada and Siberia and migrate to wintering areas further south. The 15 species of true geese are found mainly in the Arctic and subarctic regions. They are gregarious and can live for a long time (captive birds live up to 50 years). Canadian geese and snow geese belong to this group.

Types of Ducks

Most ducks fall into one of three categories: 1) dabbling ducks, who spend their time near their surface and tilt their bodies so their tail sticks up when they feed; 2) shoveler ducks, who have extra wide spoon-shaped bills with fine combs for filtering out plankton and algae like baleen whales; and 3) diving ducks who disappear completely from the surface when they search for food and pop up some distance away. Shovelers include mallards, pintails and mandarin ducks.

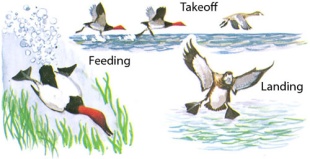

Dabbling ducks (sometimes called marsh ducks) have light bodies and float high in the water. They tend to feed by collecting stuff at the surface, or by upending their bodies and sticking their heads down into the water to reach tender buds or aquatic plants. Seldom do they actually disappear below the surface. They are fairly mobile on land as their legs are positioned forward on their bodies. They do the duck walk when they walk. Their light bodies facilitate easy takeoffs, allowing them to lift directly into the air, like a Harrier jump jet.

Diving ducks (sometimes called bay ducks or marsh ducks) have their legs set far to the back. This is good for diving but makes walking on land and taking off difficult. Their bodies and heavy and compact and they ride low in the water. Their heavy weight is suited again for diving but not for takings off. When they launch themselves from water they first run along the surface of the water to build up enough speed.

Dabblers generally feed on shallow water grasses. They do not normally dive underwater to actively pursue fish or other prey. They are so light that if they dive under water for even a second they pop right back up again. Marsh ducks dive underwater to reach clams or deep aquatic plants. Some even actively chase fish.

Anatidae — the Duck, Swan and Goose Family

Anatidae are the biological family of water birds that includes ducks, geese, and swans. These birds are adapted for swimming, floating on the water surface, and, in some cases, diving in at least shallow water. Anatids are distributed worldwide, and found in every continent except for the Antarctic region. They inhabit aquatic habitats such as lakes, ponds, streams, rivers and marshes. Some taxa inhabit marine environments outside of the breeding season. The family contains around 174 species in 43 genera. [Source: Wikipedia]

Anatidae comprises five subfamilies: Anatinae, Anserinae, Dendrocygninae, Stictonettinae, and Tadorninae. The largest subfamily, Anatinae, includes eight groups: Tadornini (shelducks and allies: five genera, 14 species); Tachyerini (steamer ducks: one genus, four species); Cairini (perching ducks and allies: nine genera, 13 species); Merganettini (Torrent Duck (Merganetta armata)); Anatini (dabbling ducks: four genera, 40 species); Aythyini (pochards: two genera, 15 species); Mergini (mergansers and allies: seven genera, 18 species); and Oxyurini (stifftails: three genera, eight species). [Source: (ADW) |=|]

Laura Howard wrote in Animal Diversity Web: Humans exploit anatids extensively. Anatids are hunted for sport and for subsistence. Many species have been domesticated for egg, meat and liver production. Eiders are raised for down (feathers) which is noted for its excellent insulating properties and is used in comforters, mattresses, pillows, and sleeping bags. Some anatids are used as 'watchdogs' as the birds are alert and provide loud alarm calls when disturbed, thereby providing property protection. When foraging in large flocks, some anatids can cause damage to agricultural crops including: potatoes, carrots, and winter wheat and barely. |=|

Thirty-eight anatid taxa are listed in the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List of Threatened Species. Five taxa are listed as 'Extinct' (Alopochen mauritianus, Anas marecula, A. theodori, Camptorhynchus labradorius, Mergus australis). Five taxa are listed as 'Critically Endangered' (Anas nesiotis, Aythya innotata, Mergus octosetaceus, Rhodonessa caryophyllacea, Tadorna cristata). Other anatids include seven listed as 'Endangered', 14 as 'Vulnerable', and seven as 'Lower Risk'. Major threats include: introduced species, human hunting and collection, habitat destruction (drainage of wetlands) and agrochemical use. Mammalian predators of anatids include: humans, red foxes, striped skunks, raccoons, badgers, coyotes, weasels and minks. Avian predators include: crows, Black-billed magpie, skuas and owls |=|

Anatidae Evolution

The oldest anatid remains may be wing fragments of Eonessa from Eocene Period (56 million to 33.9 million years ago) deposits in North America. Ramainvillia and Cygnopterus fossils have been dated from the early Oligocene Period (33 million to 23.9 million years ago) in France and Belguim. From France, Anas blanchardi has been dated to the Miocene Period (23 million to 5.3 million years ago), and Dendrochen and Mergus are known from the early and Middle Miocene Period (16 million to 11.6 million years ago) respectively. [Source: Laura Howard, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

Tadorna fossils have been recovered from the Middle Miocene Period (16 million to 11.6 million years ago) in Germany and the Pleistocene Period (2.6 million to 11,700 years ago) in North America. Paranyroca magna dates from Early Miocene (23 million to 16 million years ago) of South Dakota. In North America, anatid fossils are common in freshwater deposits of the Pliocene Period (5.4 million to 2.4 million years ago) and Pleistocene Period (2.6 million to 11,700 years ago).

The evolutionary relationships of Anatidae are vigorously debated. Generally, Anatidae is considered sister to Anhimidae (screamers) and taken together these groups form Anseriformes. Within Anatidae the monophyly of subfamilies and tribes are strongly contested. Morphological and behavioral evidence supports three subfamily divisions (Anseranatinae, Anserinae, Anatinae) within Anatidea. Anseranatinae (Magpie Goose) is hypothesized as most basal within Anatidae, and sister to the group comprising Anserinae (swans and geese) and Anatinae (ducks).

Anatidae Characteristics

Laura Howard wrote in Animal Diversity Web: Anatids are medium to large birds (30-180 centimeters; 230 grams to 22.5 kilograms). The plumage of Anseranatinae and Anserinae taxa is generally sexually monomorphic, whereas Anatinae plumage is sexually dimorphic. Plumage varies from brown, gray or white, to black and white combinations. Some anatid males and some females may have a brightly colored speculum (patch of color on the secondaries) in metallic green, bronze or blue. Juvenile plumage is duller, but often similar to adult plumage. [Source: Laura Howard, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

The neck is relatively long and the head is small. Wings are short and well -developed wing muscles insert on a deeply keeled sternum. The tail may be short and rounded or longer and narrow. The bill is broad with lamellate interior in many species. In some taxa the bill has a conspicuous horny or fleshy knob-like projection. Male bill color may be bright color at onset of breeding season. The palate is desmognathous. All species have salt glands above the eye. Legs are set far back on the body, the front three toes are webbed and the big toe is either absent or small and elevated. Male copulatory organ is present. Males also have partly or completely ossified tracheal and syringeal bullae. Oil gland is feathered. |=|

Anatidae taxa are herbivorous, although may also forage for aquatic invertebrates. Many anatids eat the seeds, roots, stems, leaves and flowers of aquatic vegetation. Some taxa feed on plankton or algae. Other food items taken include: mollusks, aquatic insects, crustaceans and small fish. |=|

Anatidae Behavior

Laura Howard wrote in Animal Diversity Web: Many anatids are migratory (make seasonal movements between regions, such as between breeding and wintering grounds), although tropical and subtropical species remain close to breeding grounds during non-breeding season. Anatids are known for their flock formations, which may serve to provide predator protection or to facilitate locating abundant food sources. Anatids may form mixed or monotypic flocks. Anatids spend copious amounts of time in the water and spend a great deal of time on preening and feather maintenance. They use their bills to coat (and waterproof) their feathers with oil from the uropygial gland. Some taxa may be forage or conduct courtship displays at night and may be seen roosting during the day. Anatids often form small groups to roost either on the water or on land. When on the water, a sleeping bird will tuck its bill under its wing; on land birds may stand on one leg. [Source: Laura Howard, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

Anatids may form small flocks or groups of up to several hundred thousand individuals. Anatids appear socially active while feeding, roosting, and migrating. Pair formation and courtship displays frequently occur in groups. Flock formation occurs predominantly outside the breeding season, although some species are colonial (live together in groups or in close proximity to each other), breeders. And some species retain cohesive family groups year round. |=|

Anatids vocalize markedly during the breeding season, as many vocalizations are integral to courtship, territorial (defend an area within the home range),ity and brood care. Most species exhibit sexual variation in vocalizations with male vocalizations often more high-pitched than female vocalizations. In general, vocalizations are varied and include: trumpeting, whistles, twitters, honks, barks, grunts, quacks, croaks and growls. |=|

Duck Mating and Child Rearing

Male ducks are ardent suitors and lovers, putting great amounts of energy into displaying to females and driving off rivals, but once the mating is over they often leave the scene and leave the roosting of the eggs and the raising of young to the females.

Most ducks make their nests on the ground in dense vegetation along the water’s edge or a short distance away. The female lines the nest with soft down plucked from her own plumage. Clutches are usually large, containing a dozen eggs. The female sits on the eggs all by herself. When she leaves to feed to she covers her eggs with grass and down to hide them.

Because only the females are around to take care after they hatch ducklings fledge and develop quickly (other bird species in which the males help raise the chicks take longer to develop). Most species of ducks are able waddle a day or two after they hatch and after that they follow their mother wherever she goes, feeding on algae, plant shoots and small insects by themselves, negating the need for her to take care of them. The mortality rate is high among duckling. They often fall prey to weasels, hawks, jungle crows, cats and snakes. By late summer only one or two are left. After that they grow up quick and are ready to mate themselves within a few months.

Anatidae Breeding and Reproduction

Laura Howard wrote in Animal Diversity Web: Most species of anatids are considered seasonally monogamous, although multiple partner copulations within a breeding season may occur in some species. Some anatids are polygynous. Mates may change from year to year in some species, or may be maintained for multiple years in other species. Pair formation often begins during the nonbreeding season. Courtship displays include head and wing movements, vocalizations and swimming patterns. Almost all species copulate on the water. In most species, the female constructs the nest while the male defends the feeding territory and guards the female as she forages.[Source: Laura Howard, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

Eggs are incubated for 22-40 days and hatching is synchronous within 24 hours. Several days prior to hatching young chicks start calling from inside the egg. Chicks are precocial (nidifugous), born with down and eyes open. Chicks can walk and swim within hours of hatching. Chicks forage for themselves while staying in close proximity of the mother. Fledging occurs at 5-10 weeks. In some species young of the year will return to the breeding grounds with parents for one or two years. Adult plumage acquisition may take one to three years. Most ducks are sexually mature at one or two years of age, whereas geese and swans may mature at five years. Life expectancy in the wild for individuals surviving their first year may be one or two additional years for ducks and four or more for geese and swans. |=|

Some anatids are aggressively territorial (defend an area within the home range), while others are colonial (live together in groups or in close proximity to each other), nesters. Colonies are generally small in size ranging from several dozen to over a hundred pairs. Anatids breed seasonally although some species maintain territories year round. Nest sites vary from shallow scrapes on land, mounds of plant material on land or water, to nest holes in trees. Nesting material includes vegetation and feathers. Clutch size ranges from 4-13 eggs with an egg-laying interval of 24 hours. Females of some species will deposit eggs in other female's nests. Some species are parasitic and will lay eggs in other species' nests. |=|

In most species females begin incubation after the last egg has been laid and continue to incubate for 22-40 days. Males generally do not incubate, but will guard the female and defend the territory. Females may cover eggs with down when they leave the nest. After hatching, the female leads chicks on foraging forays, sometimes pointing out food items and always guarding the young. Males will sometimes accompany the young and provide predator protection. Generally females guard chicks until they fledge at about five to ten weeks. |=|

Mallards

Mallards (Anas platyrhynchos) are dabbling ducks that breed throughout the temperate and subtropical Americas, Eurasia, and North Africa. Also known as wild ducks, they are one of the most recognized waterfowl and familiar duck species in the world. Both sexes have iridesent blue speculum on their wings. Males are known for the green iridesent plumage on their head and neck, and curled black feathers on the tail. The female's plumage is drab brown. These ducks averge just over a kilogram in weight. Their average lifespan in the wild is 316 months. Their average basal metabolic rate is 4.068 watts.[Source: Dave Rogers, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

Possibly extant and introduced (yellow)

Mallards can be found almost anywhere in the world. They are most numerous and widespread in in the Northern Hemisphere but can also be found easly in Oceana, Africa, South America and many islands. They live in taiga, savannas, grasslands, forests, rainforests and scrub forests are are found in lakes, ponds, rivers, streams and coastal areas. Mallards consume a wide variety of foods, including vegetation, insects, worms, gastropods and arthropods, and will take advantage of human food sources, such as grain. They prefer wetlands, where highly productive waters produce large amounts of floating, emergent and submerged vegetation as well as aquatic invertebrates on which mallards feed. |=|

Mallards are the most abundant and widespread of all waterfowl. On the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List they are classified as a species of “Least Concern”. In CITES (Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild) they have no special status. They are protected by the US Migratory Bird Act. Every year millions are taken by hunters with little effect on their numbers. As important game species, mallards generate money by license fees which pays for the management of mallard populations and is used to protect important habitats. The greatest threat to mallards is loss of habitat, but they readily adapt to human disturbances. |=|

Mallard Behavior and Reproduction

Mallards are motile (move around as opposed to being stationary), migratory (make seasonal movements between regions, such as between breeding and wintering grounds), and social (associates with others of its species; forms social groups). After the breeding season, mallards form flocks and migrate from northern lattitudes to warmer southern areas. There they wait and feed until the breeding season starts again. Some mallards, however, may choose to stay through the winter in areas where food and shelter are abundant; these mallards make up a resident populations. [Source: Dave Rogers, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

Mallards sense using vision, touch, sound and chemicals usually detected with smell. |=| The familiar "quack" of ducks is from the female mallard — it is named the "decrescendo call", and can be heard for miles. A female gives the call when she wants to bring other ducks to her, such as her ducklings, and as a result it is also known as the "hail call".

On average male and female mallards reach sexual or reproductive maturity at one year. The number of eggs laid by females each season ranges from nine to 13, with a per season average of nine. The time to hatching ranges from 26 to 28 days. Most mallard females breed as yearlings, but they may not have much success; studies show that older hens have much lower duckling mortality than yearlings. Pair bonding starts as early as October and continues through March. Mallard males leave the hen soon after mating occurs. The hen usually lays her eggs in a nest on the ground near a body of water. When the ducklings hatch the female leads them to water and does not return to the nest. |=|

Mallard Caught Going Nearly Twice the Speed Limit Is 'Repeat Offender'

Officials in the Köniz, Switzerland, believe the same mallard duck set off the same radar camera twice over seven years. People reported: A mallard duck was caught speeding, flying 52 kilometers pr hour in a 30 kilometers per hour zone — on a radar camera in Switzerland Authorities said the bird was a repeat speeding offender The same duck was caught speeding at the same spot, exactly seven years prior [Source: Rachel Raposas, People, May 15, 2025]

A radar camera in central Switzerland meant to catch cars unlawfully speeding in Köniz, a town near Bern, instead snapped a photo of a law-breaking duck, according to a Facebook post from the Municipality of Köniz. The post stated that the radar camera clocked the bird in question flying at 52 kilometers per hour in a 30 kilometers per hour zone — or roughly 32 miles per hour in an 18.6 mph zone — on April 13, 2025.

According to the post, it wasn't the bird's first offense. Authorities believe the same duck flew too fast past the same radar camera precisely seven years ago. Officials claim they have evidence that the same duck triggered the same camera on April 13, 2018. It's strange enough to find out a duck triggered a radar camera, to find out one duck is likely behind the two sightings, left police "astonished," the post read. "A duck had indeed been caught in the speed trap again, seven years to the day later, in the exact same place and traveling at exactly the same speed," the post stated, also noting that specific duck is "a notorious speeder and repeat offender."

Officials noted that it is unlikely that the footage has been manipulated, because the radar's computers are calibrated and tested each year by Switzerland's Federal Institute of Metrology. Plus, photos taken by the radar camera are sealed to prevent tampering. The duck appears to be a male mallard duck, based on its green head and distinctive ring around its neck, per All About Birds. According to the Nevada Department of Wildlife, mallards can fly 55 miles per hour while migrating, or faster when flying in the direction of the wind.

Mandarin Ducks — Symbols of Love and Fidelity

Mandarin ducks (Aix galericulata) are held in high regard in China and Japan, where they are perceived as symbols of happiness and marital fidelity. According to Chinese folklore, when a pair of Mandarin ducks becomes husband and wife, they love each other for the rest of their life. Chinese people often regard them as the symbol of love.

Mandarin ducks are unremarkable-looking birds most of the year, with a grey head and dappled brown body. But during the mating season they go through a remarkable transformation. The top of their head turns glossy green, a ruff of pointed feathers sprout from around the neck and triangular sails emerge from the wings.

Also known as Chinese wood ducks, Mandarins mainly live in river valleys and forested and mountainous areas. They prefer wooded ponds and lakes, marshland fast flowing rocky streams to swim, wade, and feed in. They eat fruit, crops and other vegetation, fish, shrimp, frogs and other small animals. They are regarded as threatened not endangered species. They can usually be found in northeast, south and east China, Taiwan, Korea, Eastern Russia and Japan but are also seen elsewhere. There is a small free-flying population in Britain stemming from the release captive bred ducks. They have been exported to the west, namely Britain, since 1745. They are bred in captivity by European avicultururalists. |=|

See Mandarin Ducks in INTERESTING BIRDS IN CHINA: CRANES, IBISES AND MANDARIN DUCKS factsanddetails.com

Harlequin Ducks

Harlequin ducks (Histrionicus histrionicus) are a species of small sea duck. They get their name from Harlequin, from the colorfully dressed clown character in historical French and Italian comedy. They are also known as painted ducks, totem pole ducks, rock ducks, glacier ducks, mountain ducks, white-eyed divers and squeakers. In the northeast this species has the nickname "The Lords and Ladies". Their lifespan in the wild is typically 12 to 14 years. [Source: Alex Riley; Matthew Johnson; Alex Riley; Matthew Johnson, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

Harlequin ducks occur in northwest and northeast North America and northeast Asia. In Asia they are found mainly in the Russian Far East and They winter along the coasts of the Bering Sea Islands, Japan, Korea and China. In northwest North America they breed in Alaska and Yukon, south through British Columbia to California. In the northeast North America they are found southern Baffin Island, northern Quebec and to Labrador southward to , and Massachusetts and Long Island. They also breed in Greenland and Iceland.

Harlequin ducks range in weight from 0.45 to 0.68 kilograms (1 to 1.5 pounds) and range in length from 35.6 to 50.8 centimeters (14 to 20 inches). Their wingspan ranges from 61 to 70 centimeters (24 to 27.5 inches). Sexual Dimorphism (differences between males and females) is present: Sexes are colored or patterned differently with the male being more colorful. Harlequin duck males have blue-grey bodies with chestnut flanks and distinctive white patches on the head and body. These white patches are outlined with black. In flight males show white on their wings with a metallic blue speculum. [Source: Alex Riley; Matthew Johnson; Alex Riley; Matthew Johnson, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

See Separate Article: HARLEQUIN DUCKS: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION factsanddetails.com

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Animal Diversity Web animaldiversity.org ; National Geographic, Live Science, Natural History magazine, David Attenborough books, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Discover magazine, The New Yorker, Time, BBC, CNN, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Wikipedia, The Guardian, Top Secret Animal Attack Files website and various books and other publications.

Last updated June 2025