WILD BOARS AND HUMANS

Gladiator versus a wild boar

Wild boars have yielded meat, grease, soap, headcheese and sausage. Their bristles have been used in brushes and their tusks have been carved like ivory. Farmers and ranchers sometimes regard wild boars as blessings in that they sometimes clear away underbrush and weeds by eating them and their roots and getting rid of snakes. Generally though they are regarded as pests. Wild boars are fond of rice and a variety of vegetables. Farmer protect their crops from wild boars by surrounding their fields with knee-high fences of corrugated plastic or aluminum sheeting.

Wild boars have been adopted as pets. They are regarded as affectionate and loyal. They even wag their tails like dogs and like to be scratched behind the ears. The favorite food of one wild boar pet was Twinkies.

In the U.S., feral pigs and wild boars cause $2.5 billion worth of damage to US agriculture each year according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture. These pigs are primarily adapted to warmer climates and thus are mainly found in Texas, Florida and the southeast United States.

Many people have proposed hunting as a way to control feral pigs, but, perhaps counterintuitively, hunting can sometimes make the problem worse. Wild boar reproduce quickly and can produce large litters. They are also very adpatable. When they are hunted, they often adjust to hunters by becoming more elusive or spreading out further into new places, ultimately helping their numbers grow. [Source: Kelsey Vlamis, Business Insider, April 4, 2023]

RELATED ARTICLES:

WILD BOARS: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION factsanddetails.com

WILD BOAR ATTACKS factsanddetails.com

PIGS: CHARACTERISTICS, HISTORY, PRODUCERS AND PORK-EATING CUSTOMS factsanddetails.com

WILD PIGS OF SOUTHEAST ASIA AND INDONESIA factsanddetails.com

BABIRUSA: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR, SPECIES AND THEIR UNUSUAL TUSKS factsanddetails.com

History of Wild Boars and People

In prehistoric times people found that young boars could be kept in the villages and bred. As time went on domesticated wild boars evolved into domesticated pigs. Pigs are believed to have been domesticated from boars 10,000 years ago in Turkey, a Muslim country that ironically frowns upon pork eating today. At a 10,000-year-old Turkish archeological site known as Hallan Cemi, scientists looking for evidence of early agriculture stumbled across of large cache of pig bones instead. The archaeologists reasoned the bones came from domesticated pigs, not wild ones, because most of the bones belonged to males over a year old. The females, they believe, were saved so they could produce more pigs.

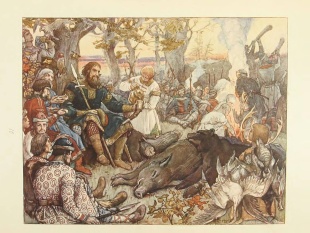

The ancient Greeks greatly admired wild boars. On how a hunter should attack a boar, the historian Xenophon (430 -354 B.C.) wrote: “As he holds out his spear, he must take care lest the boar, by turning his head aside, wrest it out of his hand; for he will follow up the charge after it is thus wrested. Should he have this misfortune, he must throw himself flat upon his face, and cling to whatever substance is below him; for, if the boar fall upon him in this position, he will be unable to seize his body on account of his tusks being turned up; ' but if he attack him standing erect, he must necessarily be wounded. The boar will accordingly endeavour to raise him up; and if he cannot do so, will trample upon him with his feet. When he is in this perilous condition, there is but one mode of delivering him from it, which is, for one of his fellow-hunters to come up close to the animal with his spear, and irritate him by feigning to throw it; but he must not throw it, lest he should hit his companion who is on the ground.

Wild Boar Hunting

“When the boar sees him doing this, he will leave the man whom he has under him, and turn with rage and fury on the one who is provoking him. The other must then jump up, but take care to do so with his spear in his hand; for there is no honourable way of saving himself but by overcoming the boar. He must therefore present his spear in the same manner as before, and thrust it forwards within the shoulder-blade, where the throat is, and must hold it firm and press against it with all his might. The boar will advance upon him courageously, and, if the guards of the spear did not prevent him, would push along the handle of it until he reached the person holding it. Such is his vigour that there is in him what no one would suppose; for so hot are his tusks when he is just dead, that if a person lays hairs upon them, the hairs shrivel up; and when he is alive, they are actually on fire whenever he is irritated; for otherwise he would not singe the tips of dogs' hair when he misses inflicting a wound on their bodies.”

For centuries, hunting wild boar was a favorite sport among European aristocrats. A special breed of dogs call boar hounds was developed for the sport. In England, wild boars were hunted so enthusiastically they disappeared there. In some places it was considered more sporting to hunt them with spears rather than guns. Pigs were introduced to Hawaii where they became destructive but tasty invasive wild boars. People there have traditionally hunted wild boars there with knives. According to Listverse The technique involves stalking the hogs, chasing them down with dogs, and then pouncing for the fatal stab. Knives are considered both more traditional and safer than bullets on a crowded island.[Source: Abraham Rinquist, Listverse, September 16, 2016]

Wild boars are one of the most popular game animals for hunters as they are not endangered, hunting them is considered sporting and their meat tastes good. They become sexually mature at a young age and may reproduce up to twice a year, producing large amounts of offspring for hunting. Hunters shoot boars for sport and for varmint control. Bait used to attract wild boars include Boar Mate (a female pheromone), corn mash, corn mash with spoiled milk, corn mash with strawberry flavoring (for juveniles) and corn mash with beer (for adults).

Recreational fee-hunting for wild boars is fairly common. The practice can be beneficial to both wildlife and landowners. They money earned by proprietors, which allows them to take better care of their property. This in turn gives the wild boar and other animals on the property a good habitat. At the same time, numbers of wild boars, which can be destructive when present in large numbers, are controlled. Hunting on wildlife reservations also increases safe hunting practices. [Source: Kristin Wickline, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

There are limits in place for hunting such as seasons and bag limits to ensure they are not over-harvested. There are also specific hunting methods that may be implicated depending on what end result is desirable. "Espera" hunting is done at night using bait to lure wild boars. This allows for a more precise harvest because it gives the hunter more time. If the purpose of hunting is to rid or thin out populations, this helps hunter determine the gender and age of the boar.

Wild boar hunters in some places traditionally pursued them on horses and generally used two kinds of dogs: chase dogs, which did as their name implies; and catch dogs that held the pig at bay after it has been cornered. Topnotch catch dogs were highly prized. They were courageous—leaping on boars several times size—and sold for a thousand dollars or more. Hunters often took a needle and thread with them on a hunt to stitch up dogs that were ripped open by a boar's tusks. In some places young boars were captured and castrated. Castration, it is said, improves the quality and taste of the meat when the animals are later killed.

Boar Hunting with Brezhnev by Henry Kissinger

Henry Kissinger wrote in Time magazine: On May 4, 1973, only four days after H.R. Haldeman and John Ehrlichman resigned as part of President Nixon’s effort to put Watergate behind him, I was airborne for Moscow. At that time, Soviet-American relations were unusually free of tension. A summit between Leonid Brezhnev [then the leader of the Soviet Union] and Richard Nixon was to take place in June on American soil; my few days in the Soviet Union in May were to prepare for it. On this trip I had a glimpse of Brezhnev that intrigues me to this day when I reflect on whether there can ever be a stable coexistence between the U.S. and the Soviet Union. [Source: Henry Kissinger. Time magazine, March 15, 1982]

One afternoon I returned to my villa and found hunting attire, an elegant, military-looking olive drab, with high boots, for which I am unlikely to have any future use. Brezhnev, similarly attired, collected me in a jeep. I hate the killing of animals for sport, but Brezhnev said some wild boars had already been earmarked for me. Given my marksmanship, I replied, the cause of death would have to be heart failure. Still, I would be willing to go along as an adviser.

Deep in the stillness of the forest a stand had been built about halfway up a tree, with a crude bench and an aperture for shooting. All was still. Only Brezhnev’s voice could be heard, whispering hunting tales: of his courage when a boar once attacked his jeep; of the bison that stuffed itself with the bait laid out for other animals and then fell contentedly asleep on the steps of the hunting stand, trapping Soviet Defense Minister Marshal Rodion Malinovski in the tower above until a search party rescued him.

After Brezhnev felled a huge boar with a single shot, we moved to another stand even deeper in the forest. We remained there for some hours, and someone brought cold cuts, dark bread and beer from the jeep. Brezhnev’s split personality—alternatively boastful and insecure, belligerent and mellow—was in plain view as we ate in that alfresco setting. The truculence appeared in his discussion of China. He spoke of his brother, who had worked there as an engineer before Khrushchev removed all Soviet advisers. He had found the Chinese treacherous, arrogant, beyond the human pale. They were cannibalistic in the way they destroyed their top leaders (an amazing comment from a man who had launched his career during Stalin’s purges); they might well, in fact, be cannibals. Now China was acquiring a nuclear arsenal. The Soviet Union could not accept this passively; something would have to be done. He did not say what.

For the complete article from which the material here is derived see HUNTING WITH BREZHNEV time.com

Wild Boars as Pests

Pigs and wild boars have traditionally been forest creatures that fed on acorns. In many places they are regarded as pests. In the summer some farmers sleep in their fields to protect their crops from wild boars. Rooting wild boars have torn up the landscape and spoil water supplies with their wallowing behavior. They also drive out other animals out by consuming most of the food. Once in Florida, a F-16 hit a wild boar on a runway and its landing gear collapsed and the plane crashed. Fortunately the pilot as able to eject and survived.

According to Animal Diversity Web: Crops are often damaged where wild boars are prevalent. While foraging for food and seeking shelter, they often trample through farm fields. In addition, wild boars have the potential to harbor several diseases and parasites that may be transmissible to domestic livestock and humans. Livestock often contract diseases from being in close proximity with wild boars. Humans may come into contact with infection by either ingesting the meat of a domestic animal that came into contact with an infected wild boar, or eating the meat of a sick wild boar. The damage caused by wild boars can be very costly, especially to farmers. In addition to losing money on their damaged crops and either loosing or having to treat their infected livestock, they may have to build better barriers to keep the wild boars out. [Source: Kristin Wickline, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

Damage caused by introduced wild boars can be so detrimental to some environments that it may lead to endangerment and extinction of native flora and fauna. In particular, the Galapagos Archipelago has had major repercussions since their introduction shortly after Darwin's visit to the islands. Because of their omnivorous foraging tendencies, these pigs have wreaked havoc on many of the islands indigenous plants and animals alike. Eradication measures have been implemented since the late-1960s and have proved successful in purging the foreign species from Santiago Island in particular, the largest introduced pig removal. Close to 19,000 wild pigs were eliminated from the island. |=|

Crossbreed Wild-Boar Super Pigs Cause Havoc in Canada and Scotland

Crosses between domestic pigs and wild boars intentionally bred in Canada and Scotland are causing havoc there. These 'super pigs' "are the worst invasive large mammal on the planet. Period," Ryan Brook, a wildlife researcher and professor at the University of Saskatchewan who has studied the pigs for more than a decade, told Business Insider. Kelsey Vlamis wrote in Business Insider: European wild boars were first brought to Canada in the 1980s in an effort to introduce a new and exotic pork product that could be uniquely marketed and served at upscale restaurants. But as the boars started popping up on farms across Canada, they were crossbred with traditional domestic pigs to make the swine bigger and more prolific. The new pigs could also grow thick furry coats, equipping them to survive the exceptionally cold Canadian winters. [Source: Kelsey Vlamis, Business Insider, April 4, 2023]

But there was a problem: The traits that made the "super pigs" desirable for the meat market also made them a nightmare once they escaped. The breeders "basically turbocharged this wild boar with all the things that make it a really successful invasive species," Brook explained, adding that wild boar alone certainly would've been a problem, but the "super pigs" that were intentionally bred are even worse. Then the boar market peaked, collapsing in 2001, and many of the super pigs were simply let go. Brook said there are known occurrences of more than 300 pigs being released at one time. Others escaped, as the super pigs were stronger and more adept at getting under or over fencing.

As a result, the number of feral pigs in Canada has exploded over the past couple of decades, leaving a trail of destruction in their wake. The pigs, which can grow to be well over 600 pounds (272 kilograms), can thrive in varied landscapes, from forests to open prairies, and eat just about anything. Brook said he and other researchers refer to the pigs as an "environmental train wreck." They prey on native species like frogs and salamanders, and the nests of ground-nesting birds, like ducks and geese. They've even been found with white-tailed deer in their stomachs.

They also take a tremendous toll on the landscape, both natural and agricultural. They'll feast on most agricultural crops, though "corn is king," Brook said. And unlike a deer, which can graze on grass, mowing along without doing much damage, pigs use their noses to root directly into the dirt. "When they push with those big, strong bodies, they just tear that ground up. They dig up plant roots, and insect larvae, and anything else they can eat in the ground," he explained, adding the "trail of destruction" makes it look as though "a small bomb went off." The exposed ground in turn makes it easier for invasive plant species to move in, and the top soil takes much longer to recover. Pigs can also contaminate water, which they roll around in to cool off and subsequently urinate and defecate in, and carry diseases that can be transferred to humans, including E. coli and hepatitis.

In July 2022, Scottish farmers reported that pig-wild-boar crossbreeds weighing more than 190 kilograms were attacking their lambs and had to be culled. The Telegraph reported: Steven MacKenzie, a Highland gamekeeper, said he had shot a boar double the normal size as it attacked one of his ewes. He believes extra protein from devouring farm animals explains why wild boars are increasing in size. The boars are descendants of animals kept on farms to provide restaurants with meat in the 1980s and 1990s. They were often crossed with domestic pigs to provide bigger litters. Some escaped and bred and there are now two major centres of population in Scotland, one in the Great Glen area and another south of Dumfries. [Source: Daniel Sanderson, The Telegraph, July 12, 2022]

“As we came into the field … we saw three pigs,” Mr MacKenzie, a gamekeeper on the Aberchalder Estate near Invergarry, said. “They had encircled a ewe. They had her on her back and they were quite literally pulling her apart and eating her. I was able to put a shot off and dispatch one of the pigs before the other two disappeared back into the forest.”

Mr MacKenzie, who shoots boars to control numbers, said sheep and lambs were being regularly killed by the animals. “They’re definitely preying on the sheep on purpose,” he added. “The majority of them are coming in at 90 to 100 kilos [15.7 stone] and they are the ones that are just on vegetation only.But we are seeing more and more bigger pigs weighing as much as over 200 kilos [31 stone], and it’s my belief that they’re only getting to that size because of the extra protein in their diet, and that protein is coming from meat.”

Wild Boar Conservation and Control

Wild boars are not endangered; in fact they are so numerous in many places they are regarded as pests. They are designated as a species of least concern on the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List and have no special status on according to the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES). [Source: Kristin Wickline, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

Wild Boars reach sexual maturity at a young age and produce large litters so there is litter danger of them going extinct. They boars can have a negative effect on the ecosystems, especially if they are an introduced species. They can be very destructive to the habitats of other animals in the area. When nesting in preparation to give birth, females use saplings and other woody plants that they either break off or uproot completely, impacting the ability of new trees to grow. When grubbing for food, they may displace soil and small undergrowth, encouraging erosion and soil deterioration. Studies have shown that seed survival and success, as well as species richness for many plants decreases in plots of land that wild boars can access. Wild boars are hard to get rid of once a population establishes itself. Their numbers may dwindle, but generally the herds bounce back.

Many programs are in place to help control and reduce wild boar populations around the world. Studies have shown that hunting is the most effective way to stabilize their numbers. Other options include installation of fencing, trapping, and strategically placed feeders to lure the boars away from inhabiting undesired areas. In some places in the southern U.S. people have resorted to using explosives to bring their numbers down.

Due to religious restrictions on the consumption of pork, some countries observe an increase in their local wild boar populations. One subspecies, Wild boar riukiuanus, was placed under the 'vulnerable' status in 1982. Widespread development of the Ryukyu Islands has threatened many endemic species, including this subspecies. They are thought to be endangered on several of the islands, although they have not been officially listed. A national park has been established, but increasing expansions looming on the horizon plan to use some of the land for roadways that will limit their habitat and give easier access to poachers who have already wiped out over half of the preserved wild boar population. |=|

Damage by Wild Pigs in the U.S.

Sara Ventiera wrote in The Guardian: Christopher Columbus brought the first eight pigs, intended as food, to the western hemisphere with his voyage to Cuba in 1493. The wild descendants of those pigs and others, estimated to number six million in 35 states, have been wreaking havoc ever since; annually, they cause $2.5 billion in damage to crops, forestry and livestock producers. They can spread disease to both humans and domestic animals. With upwards of two million of these beasts in Texas alone, the state has become the epicenter of a huge nationwide pig problem. Chef Jesse Griffiths, author of James Beard-winning “The Hog Book and Afield”, is one of the hospitality industry’s biggest advocates for consuming wild hog. “I think it’s a real easy equation: they’re invasive, they need to be removed,” he said. “The argument for a lot of other game species we eat isn’t as strong, but it is pretty glaring when it comes to hogs.”[Source: Sara Ventiera, The Guardian, July 25, 2023]

Casey Frank has seen the destruction. In June 2022, as extreme drought conditions gripped central Texas, Frank started to notice mud pits and churned-up crops around the sprinkler heads on Farmshare Austin’s 10-acre certified organic farm. A group of feral hogs — called a “sounder” — were seeking damp ground to root around for food and cool themselves during the hottest summer recorded in the state (until this year). What started as biweekly mud baths for the six full-grown hogs, which probably weighed more than 180lb apiece, soon turned into multiple wallow and pig-out sessions per week. The damage was devastating for the non-profit that cultivates new farmers and increases community food access in underserved areas of East Austin and Travis county. “It wasn’t uncommon for the hogs to come through and destroy a fifth of an acre in a night,” said Frank, Farmshare’s education and operations coordinator. “They took out at least 2,000-lb worth of produce.”

Governmental agencies, such as the USDA and state wildlife departments, have been trying to contain the population for decades. But it’s been difficult. In the 1890s, as wild game was increasingly depleted across the US landscape, elite hunters brought the first 13 Eurasian wild boars, most likely purchased from Germany’s Black forest, to a hunting preserve in New Hampshire. Notoriously smart and able to avoid capture, they were ideal targets for sport hunters craving a chase.

Frank can attest to the difficulty of tracking down even the small group of six large hogs damaging Farmshare’s property. He constructed a blind, the shelter hunters use to conceal themselves from their prey, in the middle of Farmshare’s field. For six-hour stalking sessions, he’d lie in wait with an AR-15 rifle every night. Three months in, he hadn’t shot a single one. Eventually, Farmshare Austin invested the money for traps that he filled with a pungent mix of corn in fermented beer, sugar and Jell-O. That didn’t work either. “Hogs being as intelligent as they are were able to recognize the trap and sidestep it, in spite of the fact it was baited,” he said. “It ended up being a very expensive way to feed some birds.”

Other factors have added up to a perfect storm creating one of North America’s first invasive species. In some areas, interbreeding has led to a situation that’s become impossible to control. “Domestic animals were intentionally bred to reproduce quickly at early ages in large quantities, and Eurasian wild boar were intentionally brought to be a difficult and challenging [species] to hunt,” said Mikayla Killam, wildlife damage management program specialist with Texas A&M AgriLife Extension Service. “Those two sides are really working to the hogs’ advantage.” Due to difficulty in catching them, many states with large populations allow hunters to shoot them. There is also a well-established commercial trapping industry to reduce the population of feral swine. Some of those trappers are helping to bring wild hog meat to market.

Wild Boars in Japan and China

An abundance of young wild boars bones found at archeological sites dating back at least 5,000 years indicates that Japanese boars may have been at least partially domesticated back then. Fully domesticated pigs appeared suddenly about 2,000 years ago, about the same time as paddy agriculture, which indicates both rice and pigs came together from Asia. Hunters shoot boars for sport and for varmint control. Thousands are killed each year. Boars reach sexual maturity at a young age and produce large litters so there is little danger of boars going extinct. In many places their populations are increasing. In the town of Yamada, only six were killed in 1989 while more than 700 were killed in 2006.

Many restaurants serve wild boar meat in sausages and stews. In Okayama wild boar ramen is available at local supermarkets and boar curry is served at the airport. In Kura in Hiroshima a food processing plant handles 50 to 100 boar a year. Amagi Inoshishi-mura, a village near Shuzenji Izu in in Shizuoka, features wild boars races and shows in which wild boars climb ladders, walk across a balance beam, kick a soccer ball and jump through a hoops and are rewarded with shrimp cracker after each successful feat. The village has a boar museum and restaurants that serve wild boar ramen and soba.

In the old days “mountain whale” was a euphemism for wild game. Wild boar meat is regarded as a delicacy in Japan. Takeo, a small city in the mountains of western Saga Prefecture decided to turn its wild boar pest problem into a money maker. In 2008, wild boars there cases $140,0000 in damage to rice and bean farms and hunters killed 1.541 boars. The boars used to be buried but now are processed and sold to restaurants and supermarkets, with some of profits going to hunters who shot them. The Takeo facility opened in 2009 . It is called the Takeo Meat Processing Center for Wild Birds and Animals. Half the construction cost was covered by government subsidies.

Wild boars were once protected animals in China. Now they are considered dangerous pests in many places. In Zhejiang Province, wild boar numbers increased from 29,000 to 150,000 between 2000 and 2010. To keep them from destroying crops and moving into farmland and residential areas farmers make as much noise as possible to scare them away, using vuvuzelas, gongs, karaoke machines, firecrackers and bombs, in addition to electric fences and traps. Hungry boars have moved from their mountain forest homes to forage in farmland and the residential suburbs of Hangzhou. Local officials in Zhejiang say the animal population has increased fivefold in over 10 years because villagers — their main predator — are moving into the cities and gun licences have been restricted. “The growing wild boar population is now a disaster to our village and neighboring ones. We knock on gongs, explode firecrackers and even use bombs, but there are just so many,” one villager told Xinhua. Local media have been filled with warnings of the impact on crops and other species. Corn yields in the worst affected area are expected to fall by one-third because so many plants have been trampled upon. Neighboring Jiangxi province reported a similar problem and issued 7,200 hunting licenses to cull the boar population. In Zhejiang, this has been difficult because the province borders Shanghai, which impoed gun control laws for the Expo in 2010. [Source: Jonathan Watts, The Guardian, September 13, 2010]

See Separate Article WILD BOARS IN JAPAN factsanddetails.com; WILD ANIMALS IN CHINA factsanddetails.com

Wild Boars in Berlin

In most of the world's cities about the only place you will find wild boars is in the zoo, but that is not the case with Berlin, which is overrun with them, or at least that was the case in the 1990s. Not only can they be found in Berlin’s vast parks they can also be found in swimming pools, around garbage cans and even in the basements of pricey luxury homes. [Source: Greg Steinmetz, Wall Street Journal, December 27, 1995]

The wild boar situation got so out of hand in the 1990s that the city government recruited local hunters to cull them. "I’ve never seen so many pigs as in Berlin," one hunter told Greg Steinmetz of Wall Street Journal."

Like East Germans people, pigs in East Berlin were prevented from following traditional migration patterns to West Berlin by mine fields, barbed wire, concrete walls and armed guards. When the wall came down in 1989 the pigs began migrating to western residential areas where they were often welcomed with servings of leftover potatoes, dumplings and sausage. The wild boars, apparently happy with the reception they received, began breeding in people's backyards there.

"People think they are so cute, so they like to feed them, a park ranger told Steinmetz, "but after a while they are not wild boars anymore. They're house pigs." To keep the pigs out their gardens some Berliners have resorted to firing rockets after discovering that spraying them with a hose wasn't enough.

The pigs like to go to cemeteries and eat the crocuses. A cemetery near the stadium for the 1936 Olympics spent thousands of dollars on new fences and has a sign reading "Danger: Wild boars."

Wild boars and dogs seem to have a natural loathing for each other. One woman told Steunmetz that she beat up a pig with a leash after it lunged and bit her dog. "If someone you love is in danger, you don't think about yourself, she said. One pig chased a woman down the street and she was forced to jump a fence and run through several backyards to get away. "I was terrified," she said.

In an attempt to control the pigs, park rangers have sprayed fences with "a smelly goo of concentrated human sweat." "Pigs were supposed to be repelled," Steinmetz wrote, "But while people living downwind complained of the odor, the pigs got used to it and kept coming." Pig traps that were supposed to help rangers capture wild boars and move them to a new location caught more dogs and cats than pigs.

Radioactive Wild Boars of Germany — Not Just From Chernobyl

In the forests of southern Germany, groups of radioactive wild boars have been known to bite and charge people, often as a result of being highly protective of their young. They contain such high levels of radioactive cesium 137 have been declared unsafe to eat. [Source: Tony Ho Tran, The Daily Beast, August 31, 2023]

Jacklin Kwan wrote in Live Science: After puzzling scientists for decades, researchers have finally figured out what's making Bavaria's wild boars radioactive, even as other animals show few signs of contamination. Turns out, according to a study published in August 2023 in the journal American Chemical Society, the animals are still significantly contaminated with radioactive fallout from nuclear weapons detonated over 60 years ago — not just from the Chernobyl disaster, as was previously thought. And the boars are likely being contaminated by some of their favorite food — truffles. [Source: Jacklin Kwan, Live Science, September 7, 2023]

Bavaria, in southeastern Germany, was hit with radioactive contamination following the Chernobyl nuclear accident in April 1986, when a reactor exploded in Ukraine and deposited contaminants across the Soviet Union and Europe. Some radioactive material can persist in the environment for a very long time. Cesium-137 — which is associated with nuclear reactors like at Chernobyl — takes around 30 years for its levels to be halved (known as its half-life). In comparison, cesium-135, which is associated with nuclear weapon explosions, has a half life of 2.3 million years.

Boars in Bavaria have continued to have high radioactivity levels since the Chernobyl disaster, even as contaminants in other forest species declined. It was long theorized that Chernobyl was the source of the radioactivity in boars — but something didn't add up. With cesium-137 having a half-life of 30 years, the boars' radioactivity should be declining, yet it is not. This is known as the "wild boar paradox."

But now, in a new study published in the journal Environmental Science and Technology on August 30, scientists found that fallout from nuclear weapons testing during the Cold War is behind the wild boar paradox, with radioactive material from both Chernobyl and nuclear weapons tests accumulating in fungi, such as deer truffles, that the boars consume.

The researchers analyzed the meat of 48 boars in 11 Bavarian districts between 2019 and 2021. They used the ratio of cesium-135 to cesium-137 in the samples to determine the source. The specific ratios between these two isotopes are specific to each source of radiation, forming a unique fingerprint that researchers can use in analysis — a high ratio of cesium-135 to cesium-137 indicates nuclear weapon explosions, while a low ratio suggests nuclear reactors.

They compared the isotopic fingerprint of the boar meat samples with soil samples from Fukushima and Chernobyl, as well as from historical human lung tissue collected in Austria. The lung tissue was processed in the 1960s and revealed signs of the isotopic fingerprint left by nuclear weapons testing during the Cold War. While no nuclear weapons were detonated near the study site, fallout from the tests spread in the atmosphere globally. Findings showed that 88 percent of samples taken exceeded the German limit for radioactive cesium. Between 10 percent and 68 percent of contamination came from nuclear weapons testing. The contaminants from both the weapons test and Chernobyl disaster seeped deep into the earth and were absorbed by underground truffles, explaining the wild boar paradox.

Invasive Wild Boars in Modern Rome — Are Wolves the Solution?

Italy is home to an estimated 2.3 million boars. Each year, they cause €200 million of damage to crops, as well as traffic accidents when they are hit by vehicles while crossing roads. One aggressive animal bit a boy’s genitals on an island off Sardinia in September 2024. [Source: Henry Samuel, The Telegraph, February 3, 2025]

Bethany Dawson wrote in Business Insider: Rome, is being overrun by wild boars. But instead of man-made solutions to the troublesome invasion on four trotters, nature could come to the rescue of harassed Romans thanks to the return of wolves to the city's fringes, experts told The Times. The newspaper writes that there could be thousands of boars wandering the streets of Rome, scaring the citizens and devouring piles of rubbish left on the roads. For example, in 2021, a boar gang surrounded a woman in a supermarket car park near Rome, forcing her to drop her shopping which they then devoured, said The Times. [Source: Bethany Dawson, Business Insider, June 19, 2022,]

But it's not just their 200-pound stature and sharp tusks that scare the locals, but the soaring cases of African swine fever affecting domestic pigs, which — while harmless to humans — pose a serious threat to the production of Italy's famed prosciutto ham. To cull the population of boars, the Italian government's anti-boar tsar Angelo Ferrari told The Times that fencing had been erected along Rome's 68km surrounding ring road. "The plan is for all those inside the ring road to get infected and die, even as we carry out a significant depopulation outside the city," he said.

Then, hunters in the Lazio region around Rome were given extra hunting permits to continue the cull, with officials hoping 50,000 could be destroyed. But this isn't a definite answer to Rome's boar problem. Maurizio Gubbiotti, the head of Rome's parks and nature reserves, told The Times, "it's very hard to hermetically seal off that much ring road." In addition to this, environmental activists have denounced this approach by staging protests and tearing down fencing.

It's Italy's growing population of wolves that may provide an answer to the marauding boar. In 2013 researchers found the first proof of a wolf's presence in Castel di Guido Reserve, inside the municipality of Rome, their first sighting in more than a century, the European Wilderness Society reported. Once barely traceable in Italy, the wolves are now returning, and Gubbiotti told The Times that they are now being sighted on the edge of Rome, where they could be feasting on wild boar who retreat to wooded areas when they are not feeding. He said traces of boar remains are already showing up in their feces in the Insugherata nature reserve near Rome, evidence that they're already contributing to the cull. "The equilibrium is coming," said Gubbiotti.

Wild Boar Population Explosion Causes Chaos for French Train System

Henry Samuel wrote in The Telegraph: France’s national rail has declared war on wild boars that are running amok on tracks, causing thousands of hours of delays and millions of euros worth of damage. Despite culling around a million per year, it is estimated that France’s wild boar population has ballooned to more than two million today thanks to plentiful food supplies and larger litters in milder winters. That’s up from 300,000 in 1995. They have uprooted farmers’ fields and private gardens, and have become the bête noire of SNCF, the national rail operator, which is teaming up with hunters using heat-seeking drones to deal with the growing problem. [Source: Henry Samuel, The Telegraph, February 3, 2025]

The boars, which are are known as sangliers and can weigh more than a quarter of a ton when fully grown, can cause major damage to trains. SNCF photos show a direct hit can mangle the front of their regional and fast TGVs, posing a serious security threat. Nowhere is the problem worse than in Normandy, where there were 209 collisions between trains and wild animals — mainly boar but also deer — last year, causing 22,000 minutes of delays. They estimate boar will be responsible for a third of all delays this year along the region’s 1,600 kilometers of tracks.

Barely a day goes past without some kind of incident involving sangliers. In late November 2024, passengers travelling on a train from Caen to Paris were subjected to a “nightmarish” seven hours of delays after their train stopped in a storm due to trees on the tracks only to then crash into four wild boars, which damaged the train. Emmanuel Even, a passenger, recalled that “nobody knew what was going on on this train from hell. We were told that the electricity had to be cut off, that we’d hit wild boar and that there was a fire, but they couldn’t give us a restart time,” he said. “We remained in total darkness for three and a half hours with no air-conditioning, ventilation, water or food. We had no toilets because they quickly overflowed. Eventually the police let us out to relieve ourselves.” Due to arrive in Paris at 9.26 pm on Sunday evening, the train limped into Gare Saint-Lazare at 5am on Monday morning.

Normandy is not alone. Other hotspots are the Loire, Provence, Dordogne, and Alsace. Experts say that the highly intelligent animals’ passion for railways started during the Covid pandemic when fewer trains were running and the boars could approach the tracks and reproduce in peace as many hunters remained confined. As the population has grown, so has the number of collisions — each of which causes an average of 30 minutes of delays. In 2020 there were only 619 wild boar train collisions in France. By 2022 that grew to 876 and last year there were 1,104.

In Normandy, the regional council puts the cost of damage caused by collisions at over €1 million for 2024. “It’s become a real nightmare,” Hervé Morin, the regional president, told Le Figaro, estimating that “collisions with wild boars” had risen by 40 per cent since 2020. Normandy will also fund a special train repair cen ternear Rouen to deal with boar-damaged parts.

SNCF Réseau, the rail body in charge of the tracks, has already spent hundreds of thousands of euros in fencing off the most accident-prone stretches, particularly near wooded areas, and has even come up with giant one-way “boar flaps”. The animal makes its way along the fence and reaches a kind of funnel that allows it to pass under the fence thanks to the flap, which naturally shuts behind it, meaning the boar cannot get back into the track area,” said Vincent Palix, Normandy regional director for SNCF Réseau. He said the boar flaps had reduced the number of collisions by 90 per cent in the area concerned but that it was financially unfeasible to fence the entire line.

SNCF is looking into other ways of flushing the boars out, such as experimental humane traps, underground passages and “biomimetic” sounds that resemble a “threatening large mammal” to scare the animals off as a train approaches. Hunters are not allowed to shoot boars near the tracks for obvious security reasons. Indeed, there were 90 accidental shootings of people during the 2021-22 season, and eight deaths.

But they are allowed to use heat-seeking drones. This week, the rail operator signed an agreement with the hunting federation of the Eure département to use the remote controlled aircraft to spot boars near the tracks. “We fly the drones over the track area and as soon as we see the heat of an animal, we zoom in. The form of the thermal image is sufficient to work out whether it’s a boar or a deer, rabbits,” said Nicolas Gavard-Gongallud, director of the Eure hunters’ federation. “The idea is to swiftly spot their main hideouts over a wide area of 10s of kilometers,” he told The Telegraph. If they are located on SNCF land, the operator then clears low-lying copses of the brush they need to stay out of sight. “But if they are on private land, we organise ‘administrative hunts’ to cull them”, Mr Gavard-Gongallud added.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Animal Diversity Web animaldiversity.org ; National Geographic, Live Science, Natural History magazine, David Attenborough books, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Discover magazine, The New Yorker, Time, BBC, CNN, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Wikipedia, The Guardian, Top Secret Animal Attack Files website and various books and other publications.

Last updated May 2025