BABIRUSA

Babirusa (Babyrousa babyrussa) are spectacular-looking creatures. David Attenborough wrote: “The tusks of the lower jaw of the male grow vertically upwards. Those in its upper jaw do the same thing but do not emerge from the side of the mouth. Instead they pierce the flesh of its snout and the curve backwards towards its forehead. Maybe female pigs of all species, ever since the family first appeared have always had a fancy for facial decorations in their males.” [Source: “Life of Mammals” by David Attenborough]

Babirusa are wild hog-like animals that weigh up to 100 kilograms (220 pounds) They have four unusual tusks and live along muddy rivers in the swamp forests of Sulawesi. Babirusa means "pig deer" — a name derived from the curling, deer-antler-like upper tusks of the male, which appear to pierce through the top of animal's head. They also have tusks coming out of the side of their mouth.. According to native legend, these tusks help babirusas to dangle themselves from tree branches when they sleep. The tusks actually help the animal dig up dirt in its quest for edible roots. [Canon advertisement in the November 1993 National Geographic].

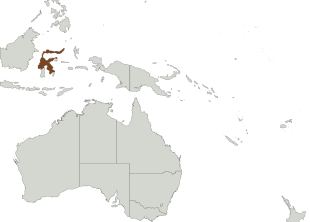

Babirusa live in Indonesia on Sulawesi, the Togian and Sula islands, and Buru island in the Moluccas. They prefers moist forests and canebrakes (thickets of bamboo and grasses) near the shores of rivers and lakes and avoid dense shrub vegetation. Despite their appearance studies of fossils have suggested that babirusa are more closely related to hippopotami than pigs. However, comparison of anatomical features such as their heart indicates they may be closer related to pigs. They are often placed in their own subfamily — Babyrusinae. Its closest relative is believed to be a European pig that became extinct 35 million years ago. [Source: Ati Tislerics, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

Babirusas are among the oldest living members of the pig (suid) family. They are believed to have diverged from the ancestors of pigs between 26 million and 12 million years ago, possibly because they became isolated on Sulawesi when sea levels dropped allowing movement to the island and then rose at the end of the last ice age. [Source Lydia Smith, Live Science, October 27, 2024]

RELATED ARTICLES:

PIGS: CHARACTERISTICS, HISTORY, PRODUCERS AND PORK-EATING CUSTOMS factsanddetails.com

WILD BOARS: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR, HUMANS factsanddetails.com

WILD PIGS OF SOUTHEAST ASIA AND INDONESIA factsanddetails.com

Babirusa Characteristics

Babirusa range in weight from 43 to 100 kilograms (95 to 220 pounds) and have a head and body length that ranges from 85 to 110 centimeters (33.5 to 43 inches). They stand 65 to 80 centimeters (25.5 to 31.5 inches) at shoulder and have a 20-to-32-centimeter (7.8-12.6-inch) tail. Their average lifespan in captivity is 24 years. Sexual Dimorphism (differences between males and females) is present: Ornamentation is different. Males have the distinctive tusk; females don’t. [Source: Ati Tislerics, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

Babirusa have a rounded body, somewhat pointed snout, and relatively long, thin legs. Depending on the species, the skin may be rough and brownish gray with only a few dark bristles (the North Sulawesi babirusa); brown to black coat, markedly lighter on the underside (Togian babirusa), or long, thick golden cream-colored and/or black coat (Buru babirusa). The skin often has large folds or wrinkles. /=\

Babirusas have relatively complex two-chambered stomachs, which are more similar to the digestive systems of sheep than those of pigs. Unlike other members of the pig family, babirusas don't have a thick rostral bone in their snouts, meaning their snouts are too weak to root in hard ground. Instead they use their hooves to dig for food. They can also stand on their two hind legs to reach fruit and leaves on trees.[Source Lydia Smith, Live Science, October 27, 2024]

Babirusa Tusks

The babirusa's most dramatic, shock-and-awe physical features are its tusks. Lydia Smith wrote in Live Science: Like human fingernails and hair, these tusk-like teeth continue to grow throughout their lifetime — and they can even grow into the skull. After protruding from the tops of the snout, the teeth look like antlers, which is how babirusas got their name — the word babirusa means "pig deer" in the Malay language. Babirusas are also sometimes called "prehistoric pigs" because they appear in cave drawings from nearly 40,000 years ago. [Source Lydia Smith, Live Science, October 27, 2024]

Scientists don't know exactly why male babirusas have these tusks. Originally, biologists believed they helped males fight each other to win mates, but babirusas don't actually use their tusks for fighting — they get up on their hind legs and box each other. Babirusa tusks are also fragile, making them unsuitable for combat. It's now thought they are used to attract females, although this theory hasn't been proven.

According to Animal Diversity Web: The upper canines of males never enter the mouth cavity but rather grow upward, pierce through the top of the snout and curve backward toward the forehead. They may reach a length of 30 centimeters (one foot). In females, the upper canines are small or absent. These tusks are brittle and loose in their sockets, apparently useless as offensive weapons, but they may help to shield the face while the daggerlike lower tusks are used in fighting. There is also evidence that on some islands these tusks are used to interlock and hold an opponent's tusks, and on other islands they are used for butting. If a male babirusa does not grind his tusks (achievable through regular activity), they can eventually keep growing and, rarely, penetrate the animal’s skull.

Babirusa Species

Babirusa are placed in the genus, Babyrousa. All members of this genus were considered to be a a single species — babirusa, B. babyrussa — until 2002. But following that was split into the following species: 1) the Buru babirusa (B. babyrussa), also known as the hairy or golden babirusa, which is covered in thick, golden hair and is native to the islands of Buru and the Sula Islands of Mangole and Taliabu; 2) Bola Batu babirusa (Babyrousa bolabatuensis), which is brown-gray in color and lives on Sulawesi; 3) the North Sulawesi babirusa (B. celebensis), also known as the Sulawesi babirusa, which lives in Sulawesi; and 4) the Togian babirusa (B. togeanensis), (Babyrousa togeanensis), which is virtually hairless and is only found on the Togian islands. Another smaller species called the Bola Batu babirusa (Babyrousa bolabatuensis) was identified by fossils on Sulawesi in the 1950s, but it is believed to be extinct. [Source Lydia Smith, Live Science, October 27, 2024; Wikipedia +]

The structure of the male's canines varies by species. The upper canines of the In the golden babirusa, are short and slender with the alveolar (bony ridge that contains the sockets of the upper teeth) rotated forward to allow the lower canines to cross the lateral view. The Togian babirusa’s tusks are similar and the upper canines always converge. The North Sulawesi babirusa has long and thick upper canines with a vertically implanted alveolar. This causes the upper canines to emerge vertically and not cross with the lower canines. +

Babirusa species also have other distinguishing characteristics. The golden babirusa has long, thick fur that is white, creamy gold, black or gold overall, and black at the rump. The fur of the Togian babirusa is also long but not as that of the golden babirusa. The Togian babirusa has tawny, brown, or black fur that is darker on the upper parts than in the lower parts. The North Sulawesi babirusa has very short hair and appears bald. The female babirusa has only one pair of teats. Compared to better-known north Sulawesi babirusa, Togian babirusa are larger, have a well-developed tail-tuft, and the upper canines of the male are relatively "short, slender, rotated forwards, and always converge". +

Babirusa Behavior and Diet

Babirusa are largely solitary, motile (motile (move around as opposed to being stationary), (remain in the same area) and diurnal (active mainly during the daytime). They are primarily active in the morning. About half of their time is spent lying down, usually sleeping. They are fast runners and good swimmers — often swimming in the sea to reach offshore islands. They construct straw nests and wallow in mud. Unlike other suids (pigs), the lower tusks are not kept sharp by wearing against the uppers; male babirusa actively hone their tusks on trees. When excited, they clatter their teeth. [Source: Ati Tislerics, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

Babirusa sense using touch and chemicals usually detected with smell. Adult males are primarily solitary, while adult females are often found in small family groups, with a few young and/or sub-adults. Groups of females and young may number up to 84 individuals, most of which contain no adult males. Males rarely travel in pairs or trios. There are almost never more than three adult females in a group. Like other suids, they are quite vocal, with a limited vocabulary of low moans or grunts. /=\

Like other wild pigs, babirusa are not believed to be particularly territorial although they do mark their home ranges in various ways. Adult males in captivity have been observed to "ploughing". When put into empty, sand-filled enclosures, they will put their snouts deep into the loose soil, kneel, and slide forward on their chests. They salivate copiously while "ploughing", suggesting that this unique behavior serves a scent-marking function.

Babirusa appear to be more specialized feeders than most suids, primarily eating foliage, leaves, fallen fruit, roots, mushrooms and fungi, tree bark, insects, fish and small mammals Their strong jaws are capable of easily cracking hard nuts. Togian babirusa feed on worms and invertebrates. The stomach diverticulum of babirusa is enlarged which is often a sign of ruminants that is not the case with babirusa. Unlike most other suids, they do not appear to use their snout to root for food. Babirusa do not have a rostral bone in their nose like other pigs do that enables them to dig

Babirusa Mating, Reproduction and Offspring

The babirusa mating system has been described as a "roving dominance hierarchy" among the males in an area. Males use their tusks to fight with other males for the right to mate with several females. The upper tusks are for defense while the lower tusks are offensive weapons. [Source: Ati Tislerics, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

Babirusa have a gestation period of 150-157 days. Female babirusa cycle lengths are between 28 and 42 days and estrus last 2–3 days. The litter size for a babirusa is usually one or two piglets. Young weigh between 380 and 1050 grams. at birth. They are usually born in the early months of the year. They are more precocial than the young of other suids, beginning to eat solid food three to 10 days days after birth and are weaned at six to eight months. Males and females reach sexual maturity in one or two years, withan average of 548 days.

North Sulawesi babirusa reach sexual maturity when they are five to 10 months old. Females have two rows of teats and will give birth to one or two piglets measuring 15 to 20 centimeters (6 to 8 inches) in length. In 2006, a male North Sulawesi Babirusa and a female domestic pig were accidentally allowed to interbreed in the Copenhagen Zoo. The offspring were five hybrid piglets, two of whom died from injuries received from their mother; the remaining three (two males and one female) were found to be infertile.

Babirusa, Humans and Conservation

The wild population of babirusas is estimated at about 4000 individuals, spread across several islands. On the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List they are listed as Vulnerable. On the US Federal List they are classified as Endangered. In CITES (Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild) they are in Appendix I, which lists species that are the most endangered among CITES-listed animals and plants. [Source: Ati Tislerics, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

The main threats to babirusa are hunting, habitat loss and predation by feral and domestic dogs. Locals on Sulawesi and other Indonesian island where babirusa are found have traditionally hunted animals for food. They were also frequently captured young and tamed. The species is kept at some zoos such as the San Diego zoo and seem to breed well enough in captivity. The largest breeding group is in the zoo in Surabaya, Indonesia. The Stuttgart Zoo coordinates a European Maintenance Breeding Program for the babirusa.

According to Animal Diversity Web: Babirusa are of interest to medical researchers, because the babirusa tusk is the only permanent natural percutaneus (passing through the skin, such as by puncture) structure. When percutaneus devices such as catheters are implanted in humans, the epidermis generally does not adhere well to the device, posing a risk of infection at the site. Researchers hope to learn how to avoid this complication by studying the babirusa, where the problem does not occur.

In Indonesia, the striking appearance of the babirusa has inspired demonic masks. The Balinese Hindu-era Court of Justice pavilion and the "floating pavilion" of Klungkung palace ruins are notable for painted babirusa raksasa (grotesques) on the ceilings. Prehistoric paintings of babirusa found in caves on the island of Sulawesi in Indonesia have been dated back at least 35,400 years. Adam Brumm, who co-authored the 2014 study dating the paintings, said "The paintings of the wild animals are most fascinating because it is clear they were of particular interest to the artists themselves." [Source: Wikipedia]

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Animal Diversity Web animaldiversity.org ; National Geographic, Live Science, Natural History magazine, David Attenborough books, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Discover magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Wikipedia, The Guardian, Top Secret Animal Attack Files website and various books and other publications.

Last updated February 2025