LYNXES

Lynxes are medium-sized wild cats with in genus Lynx in the felid (cat) family. About the size of a very large, overfed house cat, but with paws the size of a mountain lion’s, functioning like snowshoes, they are carnivorous and mainly eat mice and other similar rodents, hares and rabbits, and birds. They are are primarily ambush hunters that hide and attack their prey secretly, and kill their prey with paws and teeth.

Lynxes have a fierce nature and they are quiet, stealthy and skillful. They’re good at attacking secretly and can run very quickly. They’re also good at swimming and climbing trees. They are mostly solitary. The lynx mating season is in spring. These felids have a gestation period of two months, after which, they produce two to four young lynxes. Their lifespan in the wild is 12 to 17 years. In captivity they have lived up to 33 years. [Source: Karter Johansen, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

Abigail Tucker wrote in Smithsonian magazine: The lynx is “more yeti than cat, with a thick beard and ears tufted into savage points. Rare and maddeningly elusive, the “ghost cat”— with its ultralight frame and tremendous webbed feet — can tread on top of the six-foot snowpack. His gray face, frosted with white fur, was the very countenance of winter. He paced on gangly legs, making throaty noises like a goat’s nickering, broth-yellow eyes full of loathing.

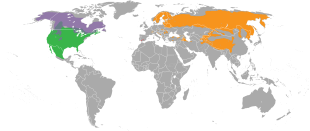

Lynxes live in forests, rocky places, plateaus and mountain areas mainly in northern regions in Europe, Asia and North America. They prefer coniferous forests and boreal forests and can be found in mid to high altitude forests with relatively dense forest floor vegetation. Many inhabit forests where the snow reaches up to the pine boughs, creating dense cover. They hunt for small game on the forest floor and are also known for their ability to catch fish from rivers. In North America populations they can be found as far south as southern Mexico, in fragments in parts of the United States, and throughout much of Canada with the exception of Nunavut in the far north. Fragmented pockets of Lynx species exist throughout the forests of Europe where they were widespread before human arrived in numbers. They are more broadly distributed throughout the large wilderness of the taiga and Siberia, with some populations reaching southwards into northern Central Asia, the Himalayas to central China. |=|

The name lynx originated from the Proto-Indo-European root-word "leuk-", meaning “light” or “brightness”, a reference to the glow of their reflective eyes. This word was picked up the ancient Greeks and then passed on to Romans and Europeans. Lynx have been featured in the mythologies of various peoples in Europe, Asia and North America and have often been depicted as elusive and having super-natural eyesight. This view made its way into one of the first scientific societies — the 17th century Accademia dei Lincei — had referred to keen eyesight of Lynx and their ability to see through falsehoods. The Roman historian Livius mentions lynx as the name for a set of games. Lynxes are the national animal of Romania and North Macedonia. An image of a lynx displayed on the North Macedonian five denar coin.

See Separate Article: EURASIAN LYNX CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION factsanddetails.com

Lynx Species

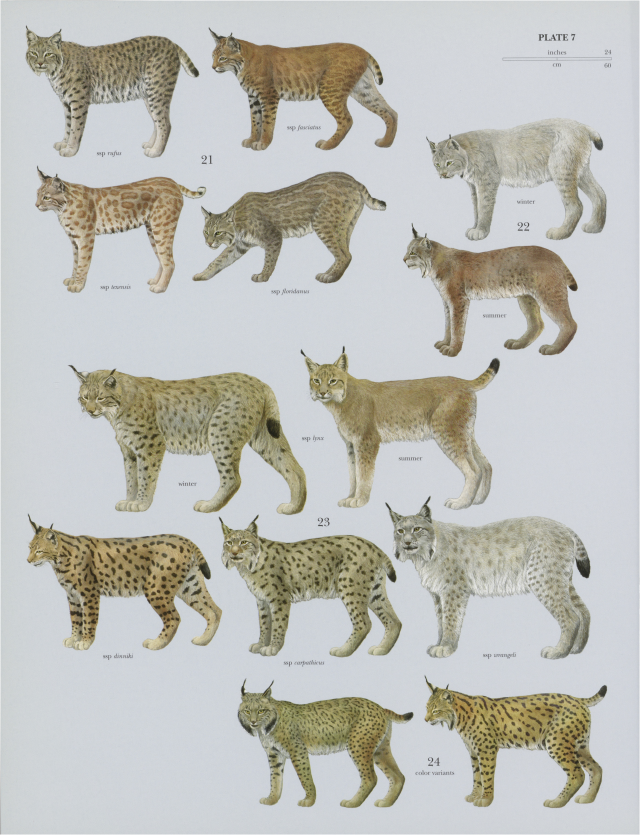

There are four species of lynx: Eurasian lynxes (Lynx lynx),Canada lynxes (Lynx canadensis), Iberian lynxes (Lynx pardinus), and bobcats (Lynx rufus). All Lynx species are obligate carnivores. This means they have to eat meat to survive and lack the digestive and metabolic abilities to properly digest plant matter and obtain necessary nutrients from it. Lynx species are fairly uniform in their general morphology and body size. They all have short tails, and ear tufts. Lynx species are mainly distinguished from one another bu their distribution and genetic make up. Their can be coloration and coat pattern differences too. [Source: Wikipedia, Karter Johansen, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

Eurasian lynxes have the widest distribution range of all lynxes. They are found in varipus parts of Europe and across a great swath of Eurasia. There are six recognized subspecies, with distinct lineages in the Balkans, Carpathian Mountains, the western and eastern halves of northern Europe, the Tibetan Plateau, and Asia-Minor. Males weigh 18 to 30 kilograms (40 to 66 pounds) and have a head body length of 81 to 129 centimeters (32 to 51 inches) and stand 70 centimeters (27½ inches) at the shoulder. Females weigh 18 kilograms (40 pounds).

Iberian lynxes were considered a subspecies of Eurasian lynxes until 2004. Both look similar to each other. Genetic data has recently distinguished the Iberian lynxes as a distinct species found exclusively on the Iberian Peninsula. They exist in a handful of relatively small populations. They were listed as Critically Endangered on International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List but in recent years have come back enough to be listed as Endangered. Males weigh 12.9 kilograms (28 pounds) and have a head body length of 85 to 110 centimeters (33.5 to 43.5 inches) and stand 60 to 70 centimeters (23.5 to 27.5 inches) at the shoulder. Females weigh 9.4 kilograms (20.75 pounds).

Canada lynxes are northernmost of the North American lynxes. It was previously thought that there were three subspecies or evens species, each found in different regions with different climates. However, recent genetic data and a further understanding of their wide dispersal ranges (of up to 1,100 kilometers) have led felid taxonomists to conclude they belong to a single species. Canada lynx weigh 8 to 14 kilograms (18 to 31 pounds) and have a head body length of 90 centimeters (35½ inches) and stand 48 to 56 centimeters (19 to 22 inches) at the shoulder.

Bobcats are found in the temperate forests and arid areas of the United States and Mexico. They are divided into species by eastern and western populations, with the barrier being relatively close to the eastern edges of the Rocky Mountains. There are two proposed subspecies of Bobcats under review in Mexico, each living in a distinct ecosystem. Males weigh 7.3 to 14 kilograms (16 to 30.75 pounds) and have a head body length of 71 to 100 centimeters (28 to 39½ inches) and stand 51 to 61 centimeters (20 to 24 inches) at the shoulder. Females weigh 9.1 kilograms (20 pounds).

Evaluation of the Felidae family using mtDNA suggest that bobcats are the most distinct and the least derived lynx. lineage. Canada lynxes and Iberian lynxes are close enough genetically and morphologically to form a monophyletic group with Eurasian lynxes. The relationship among the six established subspecies of Eurasian lynxes and three proposed subspecies is still being sorted out by scientists. The common ancestor of all for lynx species was Lynx issiodorensis, which was distributed throughout Europe and Africa from the late Pliocene Period (5.4 million to 2.4 million years ago) to Early Pleistocene Period (2.6 million to 800,000 years ago). |=|

Lynx Characteristics

Lynxes are about the size of a dog. They are smaller than a leopard and larger than a cat. They have stumpy tails, long limbs, grayish-reddish fur with spots on the legs and distinctive tufts on their pointy, erect ears. Their paws resemble small snow-shoes and are perfect for getting around in the winter. Their thick fur keeps them warm.

Lynxes have a body length of 0.90 to 1.30 meters (3 to 4.25 feet) and a short tail of 11 to 25 centimeters (4 to 10 inches) and weigh 18 to 32 kilograms (40 to 70 pounds). Sexual Dimorphism (differences between males and females) is present: Males are larger than females.

The coat patterning of Lynx species ranges from goldish-brown to beige, typically with black spotting and some black facial accents, and with a buffy white underside. The tails of Lynx species are much shorter than other felids and have a black tip. Their coats are dense and long, and get thicker around the neck during the winter. Their triangular ears are relatively large compared to their skull and have black tufts on the tips. Their legs are adapted for traveling through snow, with their long length allowing movement through deep drifts, and with large paws that disperse their body weight across a greater surface area of snow to remain on top. [Source: Karter Johansen, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

Lynx Feeding Behavior

Lynx are obligate carnivores (with a digestive system that can only process animal food not plant material). They primarily hunt rodents, hares, birds, and small ungulates, and have been observed eating, reptiles, and fish. They sometimes kill chickens and sheep. Lynx commonly share their territory with wolves and bears, but there is not so much conflict as lynx tend to feed on smaller ungulates and animals in general than wolves, who prefer larger ungulates. [Source: Karter Johansen, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

Lynx are generally solitary hunters. They hunt mainly at night using the darkness to cover their movement. They can both stalk prey and hide and ambush it. They sometimes let out a sharp howl just as the prepare to attack, momentarily confusing their prey and then pounce and make the kill. Lynx may engage in group hunts.

In Montana snowshoe hares make up 96 percent of the lynx’s winter diet. According to Smithsonian magazine: When hares are scarce, lynx also eat deer as well as red squirrels, though such small animals often hide or hibernate beneath the snowpack in winter. Hares — whose feet are as outsize as the lynx’s — are among the few on the surface. Sometimes lynx leap into tree wells, depressions at the base of trees where little snow accumulates, hoping to flush a hare. Chases are usually over in a few bounds: the lynx’s feet spread even wider when the cat accelerates, letting it push harder off the snow. The cat may cuff the hare before delivering the fatal bite to the head or neck. Often only the intestines and a pair of long white ears remain. [Source:Abigail Tucker, Smithsonian magazine, February 2011]

Lynx in some places feed primarily on rabbits and on average feed on two rabbits a day. They often roam around and wait for a rabbit to cross their path. Then they go into a crouch and quietly stalk their prey. When the rabbit notice the lynx and begin to flee the lynx sprints with a quick burst of speed towards the zigzagging rabbit. Often it makes a kill. A famous Lynx, rabbit study showed that when the population of prey (rabbits) crashes so does that of the predator (lynx). Lynx often also compete with a lot of other animals such as foxes and weasels that also feed on rabbits.

Lynx are apex predators in their trophic systems and have no natural predators. Lynx cubs are at risk of predation by other predators, such as wolves, coyotes, and cougars. As apex predators, lynx play vital roles regulating the populations of small vertebrates in their ecosystems. Roe deer (Capreolus capreolus) and red deer (Cervus elaphus) are prime examples. Because Lynx species are apex predators, they also are used as a reliable indicator of ecosystem health. |=|

Lynx Behavior

Lynxes are nocturnal (active at night), crepuscular (active at dawn and dusk), motile (move around as opposed to being stationary) and territorial (defend an area within the home range). The majority of social activity occurs between mothers and their cubs during the first year of the cubs’ life, as well as brief interactions between males and females during the winter breeding season. Lynx have excellent reflexes and are adept swimmers.[Source: Karter Johansen, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

Females usually divide their habitat into territories that remain stable for years. The average territory is around nine square kilometers (3½ square miles). Males also have their own large territories (often 18 square kilometers, seven square miles or more) which overlap with the female's territory in complex ways. The territorial range of lynx varies with latitude, with the southerly populations having territories of several square kilometers. Further north, where prey is more scarce, Lynx species’ territories are recorded to be up to 1100 square kilometers.

Lynxes are largely solitary animals. They are very agile and are adept good climbers but spend much of their time on the ground. They have been observed sunning themselves on the branches of trees. However, most lynx activity occurs at night. Hunting is aided partially by excellent night vision, but lynx rely heavily on hearing to locate prey. Lynx that don’t hunt alone are usually mothering teaching their cubs to hunt.

Abigail Tucker wrote in Smithsonian magazine: Lynx spend hours at a time resting in the snow, creating ice-encrusted depressions called daybeds, where they digest meals or scan for fresh prey...Like raptors, lynx also can fly, or so it has sometimes seemed to John Squires, who studies them. During hunts the cats leap so far that trackers have to look hard to spot where they land. Squires has watched a lynx at the top of one tree sail into the branches of another “like a flying squirrel, like Superman — perfect form. ”[Source:Abigail Tucker, Smithsonian magazine, February 2011]

Squires’ research has shown time and again how particular lynx are. “Cats are picky and this cat’s pickier than most,” Squires said. They tend to stick to older stands of forest in the winter and venture to younger areas in the summer. In Montana, they almost exclusively colonize portions of woods dominated by Engelmann spruce, with its peeling, fish-scale bark, and sub-alpine fir. They avoid forest that has recently been logged or burned.

Lynx Senses and Communication

Lynxes sense using vision, touch, sound, ultrasound, vibrations and chemicals usually detected with smell. Lynx have very acute eyesight. So acute that people in ancient times thought the could see through stone walls. Father Odob, an abbot of Cluny Abbey wrote in 1100, "If men were endowed, like lynxes of Boetia, with the power of visual penetration and what there is the beneath the skin, the mere sight of a woman would nauseate them: [Source: Karter Johansen, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

Lynxes have excellent vision in low-light conditions, aided by their tapetum lucidum, the reflective membrane behind the retina that makes their eyes glow in reflected light. Their triangular ears have a wide range of radial movement, allowing for highly focused hearing. Their long whiskers allow for the perception of feint vibration and movement.

Lynxes communicate with touch, sound and chemicals usually detected by smelling. They leave scent marks produced by special glands and placed so others can smell and taste them. Similar to other cats, lynx use scent glands and urine to mark territorial boundaries and communicate with others.

Little is known about lynx communication. They are mostly silent and generally very quiet animals. Low guttural calls are emitted during breeding. Cubs cry for help. Tigers, lynxes and pumas can purr like house cats. The sudden nighttime cry of the lynx has sent shivers down the spines of men since the dawn of mankind. It usually consists of single sharp howl followed by silence. This is believed to be used in hunting to confuse prey right before the lynx pouces to make the final kill.

Lynx species: 21) Bobcat (Lynx rufus), 22) Canadian Lynx (Lynx canadensis), 23) Eurasian Lynx (Lynx lynx), 24) Iberian Lynx (Lynx pardinus)

Lynx Mating, Reproduction and Offspring

Lynx are monogamous (have one mate at a time) and polygynandrous (promiscuous), with both males and females having multiple partners. Females usually mate with males in adjoining territories and males mate with as many females as they can. Sometimes lynx pair off into monogamous couples living side by side in adjoining territories. Pairs typically come together briefly to mate in the winner. Mating pairs do not remain together pre- or post-copulation and both sexes will have multiple partners if prey density allows individual territories to overlap. On choosing partners, Minnesota biologist Craig Packer told National Geographic, “Size does matter” though more for male competitions than female preference

The lynx mating season begins in early spring, ranging from January to July, with it arriving a couple months later for populations living in northern latitudes than for those further south. The gestation period is 55 to 74 days. The gestation period varies between species, with larger species having slightly longer gestations. Typical litter sizes ranges from one to five, with two to three cubs being most common. [Source: Karter Johansen, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

Young are raised entirely by the mother and are weaned around six months of age when cubs are able to accompany the mother on hunts. Female usually find a burrow, shallow cave or hollowed out tree trunk to give birth and den in. Reproduction takes place in the early parts of spring in order to allow Lynx species to rear cubs to self-reliance before the next winter arrives. After the cubs are born they remain in the hollowed tree with their mother several weeks. At this time the territory of the mother shrink to perhaps 2.6 square kilometers (one square mile) because they want to stay close to their cubs. After that the mother moves her young around frequently until they can take care of themselves.

The parental investment required for rearing cubs to maturity lasts between 10 and 12 months. During the first two to six months of their life cubs live off milk from their mother. Upon being weaned, the mothers provide fresh meat, eventually bringing her cubs along to learn to hunt for themselves. Upon reaching maturity, the offspring emigrate out of the mother's territory in search of their own.

Lynx Populations

Abigail Tucker wrote in Smithsonian magazine: lynx are among the most fecund cats in the world, able to double their numbers in a year if conditions are good. Adult females, which have an average life expectancy of 6 to 10 years (the upper limit is 16), can produce two to five kittens per spring. Many yearlings are able to bear offspring, and kitten survival rates are high. [Source: Abigail Tucker, Smithsonian magazine, February 2011]

The northern lynx population rises and falls according to the snowshoe hare’s boom-and-bust cycle. The hare population grows dramatically when there is plenty of vegetation, then crashes as the food thins out and predators (goshawks, bears, fox, coyotes and other animals besides lynx) become superabundant. The cycle repeats every ten years or so. The other predators can move on to different prey, but of course the lynx, the naturalist Ernest Thompson Seton wrote in 1911, “lives on Rabbits, follows the Rabbits, thinks Rabbits, tastes like Rabbits, increases with them, and on their failure dies of starvation in the unrabbited woods.” Science has borne him out. One study in a remote area of Canada showed that during the peak of the hare cycle, there were 30 lynx per every 40 square miles; at the low point, just three lynx survived.

The southern lynx and hare populations, though small, don’t fluctuate as much as those in the north. Because the forests are naturally patchier, the timber harvest is heavier and other predators are more common, hares tend to die off before reaching boom levels. In Montana, the cats are always just eking out a living, with much lower fertility rates. They prowl for hares across huge home ranges of 60 square miles or more (roughly double the typical range size in Canada when the living is easy) and occasionally wander far beyond their own territories, possibly in search of food or mates. Squires kept tabs on one magnificent male that traveled more than 450 miles in the summer of 2001, from the Wyoming Range, south of Jackson, over to West Yellowstone, Montana, and then back again. “Try to appreciate all the challenges that animal confronted in that huge walkabout. Highways, rivers, huge areas,” Squires says. The male starved to death that winter.

Lynx, Humans and Conservation

Lynx have vanished from much of their former ranges. They have been hunted for sport and pelts and killed for being a livestock-killing pest. Their pelts have been used for expensive fur coats. When fur was fashionable (an it still is in Russia and China) lynx pelts were highly sought after and lynx were trapped to obtain their fur — a practice blamed for greatly for greatly reducing in numbers of lynx in all species, driving some species and to near extinction. Lynx are also effective at limiting ungulate populations, keeping populations from growing too large and damaging forest ecosystems. |=|

On the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List, Eurasian lynx, Canada lynx and bobcats are listed as species of Least Concern. The Iberian lynx was listed as Critically Endangered then moved to Endangered and moved again to Vulnerable. [Source: Karter Johansen, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

Lynx species have been known to take livestock and pets, leading to some communities to kill them as pests. Their hunting patterns have also been blamed for reducing game species numbers. This has led some governments to compensate hunters and farmers for the economic damages caused local lynx activity. All ‘n all, lynx take relatively few livestock animals; attacks on pets are rare; and most places have not experienced a reduction of game animals because of lynx. Lynx aggression towards humans is uncommon and results mostly from lynx kept as pets by humans.

A majority of Lynx species have recovered from fur trade practices, with overall population sizes of Eurasian lynxes and Bobcats reaching well over a million individuals. Eurasian lynxes and Canada lynxes have both been the target of reintroduction efforts and are actively protected by most governments in their range. Even Iberian lynx have bounced back after hoovering on the edge of extinction.

Abigail Tucker wrote in Smithsonian magazine: The lynx’s future depends in part on the climate. A recent analysis of 100 years of data showed that Montana now has fewer frigid days and three times as many scorching ones, and the cold weather ends weeks earlier, while the hot weather begins sooner. The trend is likely the result of human-induced climate change, and the mountains are expected to continue heating up. This climate shift could devastate lynx and their favorite prey. To blend in with the ground cover, the hare’s coat changes from brown in summer to snowy white in early winter, a camouflage switch that (in Montana) typically happens in October, as daylight grows dramatically shorter. But hares are now sometimes white against a snowless brown background, possibly making them targets for other predators and leaving fewer for lynx, one of the most specialized carnivores. “Specialization has led to success for them,” says L. Scott Mills, a University of Montana wildlife biologist who studies hares. [Source: Abigail Tucker, Smithsonian magazine, February 2011]

Studying Lynx

John Squires is the leader of the U.S. Forest Service’s lynx study at the Rocky Mountain Research Station in Missoula, Montana.Abigail Tucker wrote in Smithsonian magazine:The chances that we’ll trap and collar a lynx today are slim. The ghost cats are incredibly scarce in the continental United States, the southern extent of their range. Luckily for Squires and his field technicians, the cats are also helplessly curious. [Source: Abigail Tucker, Smithsonian magazine, February 2011]

The study’s secret weapon is a trick borrowed from old-time trappers, who hung mirrors from tree branches to attract lynx. The scientists use shiny blank CDs instead, dabbed with beaver scent and suspended with fishing line near chicken-wire traps. The discs are like lynx disco balls, glittering and irresistible, drawing the cats in for a closer look. Scientists also hang grouse wings, which the lynx swat with their mammoth paws, shredding them like flimsy pet store toys.

If a lynx is enticed into a trap, the door falls and the animal is left to gnaw the bunny bait, chew the snow packed in the corners and contemplate its folly until the scientists arrive. The lynx is then injected with a sedative from a needle attached to a pole, wrapped in a sleeping bag with plenty of Hot Hands (packets of chemicals that heat up when exposed to the air), pricked for a blood sample that will yield DNA, weighed and measured and, most important, collared with a GPS device and VHF radio transmitter that will record its location every half-hour. “We let the lynx tell us where they go,” Squires says. They’ve trapped 140 animals over the years — 84 males and 56 females, which are shrewder and harder to capture yet more essential to the project, because they lead the scientists to springtime dens.

Of the animals that died while Squires was tracking them, about a third perished from human-related causes, such as poaching or vehicle collisions; another third were killed by other animals (mostly mountain lions); and the rest starved.

To follow the cats into the folds of the Rockies, Squires employs a research team of former trappers and the hardiest grad students — men and women who don’t mind camping in snow, harvesting roadkill for bait, hauling supply sleds on cross-country skis and snowshoeing through valleys where the voices of wolves reverberate.

In the early days of the study, the scientists retrieved the data-packed GPS collars by treeing lynx with hounds; after a chase across hills and ravines, a luckless technician would don climbing spurs and safety ropes, scale a neighboring tree and shoot a sedation dart at the lynx, a firefighter’s net spread below in case the cat tumbled out. (There was no net for the researcher.) Now that the collars are programmed to fall off automatically every August, the most “aerobic” (Squires’ euphemism for backbreaking) aspect of the research is hunting for kittens in the spring.

Such data are instrumental for forest managers, highway planners and everyone else obligated by the Endangered Species Act to protect lynx habitat. The findings have also helped inform the Nature Conservancy’s recent efforts to buy 310,000 acres of Montana mountains, including one of Squires’ longtime study areas, from a timber company, one of the biggest conservation deals in the country’s history. “I knew there were lynx but didn’t appreciate until I started working with John [Squires] the particular importance of these parcels of land for lynx,” says Maria Mantas, the Conservancy’s western Montana director of science.

Squires’ goal is to map the lynx’s entire range in the state, combining GPS data from collared cats in the remotest areas with aerial photography and satellite images to identify prime habitat. Using computer models of how climate change is progressing, Squires will predict how the lynx’s forest will change and identify the best management strategies to protect it.

Comeback of the Iberian Lynx

In June 2024, the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN)moved the Iberian lynx from "endangered" to "vulnerable" on its Red List after a significant increase in numbers. Its population grew from 62 mature individuals in 2001 to 648 in 2022. While young and mature lynx combined now have an estimated population of more than 2,000, the IUCN said. This upgrade aoccurred after Iberian lynx were moved from "critically endangered" to "endangered" on its Red List in 2015. [Source: BBC, June 20, 2024]

As their name suggests, Iberian lynx live in the Iberian region — Spain and Portugal. The BBC reported: According to the latest census data, there were a total of 14 clusters where the animals were stable and reproducing. Of those, 13 were located in Spain and one in Portugal. The increase is largely thanks to conservation efforts that have focused on increasing the abundance of its prey — the also endangered wild rabbit, known as European rabbit. Programmes to free hundreds of captive lynxes and restoring scrublands and forests have also played an important role in ensuring the lynx is no longer endangered.

Christine Dell'amore wrote in National Geographic: In just 20 years, the Iberian lynx has gone from the world’s most endangered feline to the greatest triumph in cat conservation. The dramatic turnaround is the result of the all-out effort to breed the cats in captivity, the lynx’s status as a natural treasure, and the animal’s innate scrappiness, which has surprised even conservationists. [Source: Christine Dell'amore, National Geographic, May 5, 2022]

When the European Commission’s Life program first brought together more than 20 organizations in 2002 to rescue the lynx, the species had all but disappeared. Widespread hunting and a virus had wiped out most of the peninsula’s European rabbits, the lynx’s main prey. Lynx breed easily in captivity, however, and most of the animals that eventually were reintroduced into carefully chosen habitats throughout Spain and Portugal have thrived. Near one main release location, around southern Spain’s Sierra de Andújar Natural Park, Iberian lynx have even learned to live in neighborhoods, in commercial olive groves, and around highways — mostly by avoiding people. One mother lynx managed to hide her newborns in a house where people were throwing a party. Such adaptability boosted their numbers, and by 2015, the IUCN had reclassified the lynx’s status from critically endangered to endangered.

Woman Injured by Pet Lynx

In May 2012, A woman suffered severe injuries to her arm after her boyfriend's pet lynx got loose and attacked her in her home in Bellevue, Washington state. The incident happened in the afternoon at a house in the 1900 block of 160th Avenue NE. The 21-year-old woman was cleaning when the animal escaped its cage. "There was a lynx cat — a pet that lived in the house and a girlfriend. The cat got jealous of the girlfriend, who was vacuuming, and it jumped on her and bit her," speculated Jenee Westbend, King County Animal Control officer.[Source:KING five News, kvue.com, May 5, 2012]

KING five News reported: Police and medics were called to the scene, but the lynx was still roaming inside the house. Medics waited outside until the lynx's owner came home and kenneled the cat. Animal Control crews then went in and took the lynx away to a vet's office in Bothell, where it is currently quarantined.

Meanwhile, the woman is expected to be okay. Neighbors said they have often seen the lynx roaming behind the front windows in the house. "I kind of felt sorry for the cat living in a house, pacing back and forth, back and forth," said Bruce Walker, neighbor. It is currently illegal to have a wild cat in your home in most cases. Animal control workers said they will be investigating that while the lynx is being examined at the Bothell vet clinic. They do that every time a pet bites someone, but very rarely is the pet a lynx.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Animal Diversity Web animaldiversity.org ; National Geographic, Live Science, Natural History magazine, CNTO (China National Tourism Administration) David Attenborough books, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Discover magazine, The New Yorker, Time, BBC, CNN, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Wikipedia, The Guardian, Top Secret Animal Attack Files website and various books and other publications.

Last updated May 2025