GODZILLA

The most well-known Japanese film star outside of Japan is arguably Godzilla, the 400-foot-long, 20-story-tall beast that appeared in 24 successful Japanese cult classic films before being panned by critics in $90 million Hollywood film. In Japan, he is known as “Gorija”, an amalgam of the Japanese words “kujira” (whale) and “gorira” (gorilla), two animals chosen because they are big and powerful and, in case of the whale, because it comes from the sea.

Godzilla is a mutated monster created by a H-bomb test in the Pacific that disturbs its undersea habitat. Resembling a Tyrannosaurs Rex, he has radioactive breath, three toes on each foot, four claws on each hand and three ridges running down his back and tail. Over the course of his 40 year film career his eyes shifted from the sides of his head to the front of his face, and he has become more laid back. In most of his films, Godzilla doesn’t visibly kill anybody he just sets fire to and knocks down buildings.

The first Godzilla film was created only eight months after the United States tested a hydrogen bomb in the Pacific at Bikini island in 1954 that irradiated the crew of a Japanese fishing boat. Godzilla director Tezuka once said, “Ever since Godzilla was created as a result of atomic bomb experiments, it has been a symbol of the darker side of man. At a glance our future seems to look bright, with the magnificent development of modern science and technology. But beware. I sincerely hope we can keep Godzilla as a creature that exists only on-screen.”

In December 2004, the University of Kansas sponsored a conference to discuss Godzilla’s legacy on the 50th anniversary of the first Godzilla film, Professors from universities such as Duke, Harvard and Vanderbilt were in attendance.

Websites and Resources

Good Websites and Sources: Official Godzilla Site godzilla.co.jp/english ; Barry’s Temple of Godzilla godzillatemple.com ; Topher’s Great Godzilla Reference Pages lavasurfer.com/godzilla/topher-zilla

Links in this Website: JAPANESE FILM Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; CLASSIC JAPANESE FILMS AND FILMMAKERS Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; AKIRA KUROSAWA FILMS Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; GODZILLA Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; MODERN JAPANESE FILM INDUSTRY Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; MODERN JAPANESE FILMMAKERS AND FILMS Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; JAPANESE ACTORS AND HOLLYWOOD ACTORS IN JAPAN Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; HOLLYWOOD FILMS ABOUT JAPAN Factsanddetails.com/Japan

Books: “A Hundred Years of Japanese Film” by Donald Richie (Kodansha International, 2002); “Japanese Cinema — An Introduction” by Donald Richie (Oxford University, 1990). Good Websites and Sources on Japanese Film: Google e-book: A Hundred Years of Japanese Film by Donald Richie books.google.com/books ; Midnight Eye midnighteye.com ; Japanese Movie Listing lisashea.com/japan ;Kinema Club pears.lib.ohio-state.edu/Markus ; Japan Association for the International Promotion of the Moving Image unijapan.org/en ; Toei Uzumasa Movie Land is a theme park and movie studio were many samurai and historical drams have been shot. Website: Japan Guide japan-guide.com Asian Film Asia Society on Film asiasociety.org ; iFilm Connections — Asia and Pacific asianfilms.org ; Love Asia Film loveasianfilm.com ; Senses of Cinema sensesofcinema.com ; Illuminated Lantern on Asian Film illuminatedlantern.com

Databases, Directories, Links: Internet Movie Database /www.imdb.com ; Directory of Interent Sources newton.uor.edu ; Japanese Film Resources at the University of Iowa lib.uiowa.edu/eac/japan ; Tokyo International Film Festival tiff-jp.net ; DVDs Japanese, Chinese and Korean CDs and DVDs at Yes Asia yesasia.com ; Japanese, Chinese and Korean CDs and DVDs at Zoom Movie zoommovie.com ; CD Japan cdjapan.co.jp ;

Godzilla Films

Most Japanese Godzilla movies are pretty similar to one another: Godzilla rises from his home in the sea and lays waste to scale-model Japanese cities, while battling monsters such as Mothra, King Ghidorah, the Smog Monster and Megalon. In the end a clever scientist figures out a way to outwit Godzilla who often ends the move by walking back into the sea.

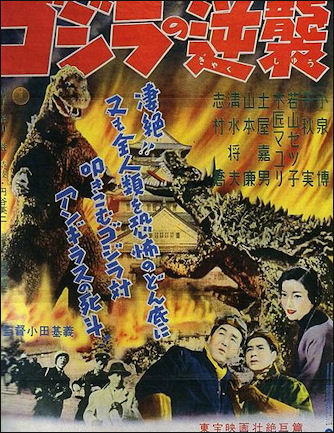

The original Godzilla film featured images of panic-stricken crowds and references to nuclear contamination, black rain and the incineration of Nagasaki and was created with the message that more monsters would be created if nuclear testing continued. The original was sold to an American distributor in 1956 that re-edited it into a typical monster running amok story with Raymond Burr as a wire reporter describing the action. Japanese footage with an anti-nuclear message was removed.

In the films in the 50s and early 60s, Godzilla was a lumbering beast that carelessly destroyed everything in its past. In the late 1960s and 1970s, when Japan was experiencing great economic growth and a general sense of optimism, Godzilla was a much more sympathetic character who fought humans but also saved them from invading aliens, creatures created by pollution and mankind's own progress-above-all-else mentality. In the 1980s and 90s, Godzilla became more selfish and self-absorbed.

The Godzilla films were originally made by Japan’s Toho Studios, which own the rights to the character, as an answer to competition from television. The budget for Godzilla films made in the 2000s was around $8 million, a pittance compared to what it takes to make a Hollywood film. Much of the money is spent on the one-25th scale city sets of Tokyo, which are made by hand and accurate down to the advertisements. electric poles and traffic signs. Waves, ash and smoke are made using agar, a substance derived from seaweed.

Godzilla was the star of the longest-running film series in cinematic history. As 2004, 28 Japanese-made Godzilla films had been made. Godzilla classics include “Destroy All Monsters” (1968) and “Godzilla versus Space Godzilla” (1972).

Godzilla Actors

Godzilla is played by an actor in a 120-pound zip up rubber suit. The actor breathes through a tube in monster’s neck. The movement of the eyes and mouth are achieved with mechanical devises.

Godzilla was played in many by Kenpachiro Satsuma. He arrived in Tokyo in the early 1970s with dreams of becoming an actor but things didn’t work out and he was forced to get a job in a steel mill, where he worked around searing heat near a blast furnace. He told National Geographic that he finally got the job playing Godzilla because “the director needed somebody could work in that hot rubber suit without passing out.” Satsuma worries about losing his job to computer graphics.

The crowds scenes are shot with no Godzilla present. The extras are told to visualize him rising out the sea and told to run with their mouths closed. A director told AP that when they have their mouths open they look like they are smiling. Cinematic tricks and camera angles borrowed from Hitchcock aim to provide suspense.

Early Godzilla Films

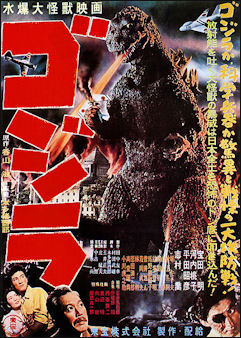

The first Godzilla film was “Godzilla, King of the Monsters” (1954), which was released in 1956 in the United States with footage of Raymond Burr, playing a reporter, edited in. The film was made by Ishiro Honda, a frequent collaborator with Kurosawa, and a rubber monster suit that weighed about 100 kilograms. Godzilla didn’t fight with any monsters, only human beings. Special effects director Eiji Tsuburaya, who later created Ultraman, was largely responsible for the Godzilla look. The film was panned by critics but drew 9.6 million people, many of whom cheered when Godzilla destroyed the Diet Building (the home of the Japanese government).

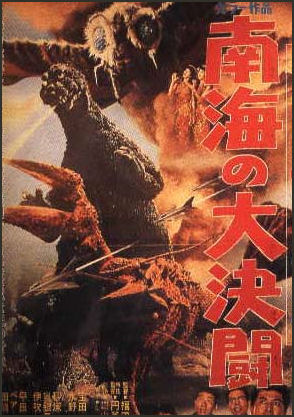

The second film made in 1955 featured some wrestling scenes between Godzilla and his foe Angiras, influenced by the professional wrestling craze that was sweeping Japan at that time, which in turn was triggered by fights between the wrestlers Rikidozan from Japan and the Sharpe Brothers from the United States. Similar fight scenes were featured in the third film “Godzilla versus King Kong” (1963),

By the fifth film, “Chiky Saidai No Kessen” (“Ghidorah, the Three-Headed Monster,” 1964) Godzilla was entering his sympathetic stage. Ghidorah was a futuristic alien than was intended to symbolize the cost of the space race between the United States and the Soviet Union. In” Godzilla Versus the Smog Monster” 91971) Godzilla’s enemy was a grotesque monster generated by pollution. In the sympathetic films Godzilla’s appearance changed. His eyes were bigger and cuter and his expression was less menacing. But this new look was less scary and thus less interesting to children and popularity of the monster declined.

Later Godzilla Films

The scary Godzilla was brought back in 1984. By this times he was much smaller in relation to the buildings in Tokyo and even at his scariest he seemed much less terrifying than monsters coming out of Hollywood. Godzilla was never able to recapture the early magic but by that time he had enough of a cult following in Japan and the West to keep the series going.

In “Godzilla versus Destroyah” (1995), Godzilla was played by Kenpachiro Satsum, who endured long sessions in the hot, confining, rubber monster suit and said he was occasionally sprayed by stagehands with compressed air to keep cool. Satsuma took his roles very seriously "What I am trying to express," he told the New York Times, "is to offer a warning against nuclear destruction."

In “Godzilla Millennium” (1999), the 23rd Godzilla film, Godzilla was given a complete going over by creature creator Shinichi Wakasa who first did a body cast of the actor inside, Tsutomu Kitagawa, and molded the suit from urethane and latex. He was also able to reduce the weight of the suit to about 70 kilograms..

“Godzilla X: Megaguirus” (2001) was the 24th Godzilla film. “Godzilla Verus Mechagodzilla” (2002), the 25th one, featured Godzilla battling a robot version of himself, which he had done three times before but this time the robot possesses genetic material from Godzilla, a comment on the cloning and genetic engineering issue. Mechagodzilla is created to fight Godzilla but rejects the command of its human owners when its G-cells come alive. The person who rescues humankind is a woman. The baseball player, Hideki Matsui, whose nickname is Godzilla, had a cameo roll in the film.

Godzilla and Japan

Monster creator Shinichi Wakasa told the Japan Times, "As a cultural icon, I don’t think there is a single person in Japan who doesn't known Godzilla in some form or another. You could say that Godzilla is the Mickey Mouse of Japan.

Kogi Osugi, an authority on Godzilla, told the Daily Yomiuri, the monster comes from sea because for Japanese “scary things always come from the sea.”

Godzilla was created at a time when Japan was still feeling the effects of Hiroshima and a group of Japanese fishermen had become seriously ill after being exposed to radiation from a test of a massive H-bomb at Bikini atoll in 1954. According to the New York Times "critics have theorized that the beast represents the horrors of nuclear war, the power of disturbed nature, or “yamato damashii”, the martial spirit of Japan."

Other rubber suit monster movies include the “Gamera” series and “Mothra” series. “Gamera 3: The Awakening of Iris” is described as one of the better films because it shows screaming people running away and getting crushed.

Godzilla versus Hollywood

The Japanese film company Toho Studios owns the rights to Godzilla. Before they allowed the Hollywood company Trip-Star to make their 1998 film, the American film executives had read a 75-page report on Godzilla (that explained thing like Godzilla eats fish not people) and agree not to dishonor the 200-foot-tall monster by deviating too much from the original story line.

Ironically the Hollywood Godzilla was well liked in Japan but panned in the West. Despite being generally regarded as a high-tech, no-brainer, “Godzilla” ended up grossing over $400 million worldwide. In Japan, half a million showed up to see it on its opening day, the largest first day audience ever for a film in Japan.

Godzilla Retires

star on the walk of fame Godzilla was retired after his last film “Godzilla Final Wars” (2004). In this film, Godzilla not only lays waste to Tokyo he always does but also does a number on Shanghai, New York and Paris. The theme song is performed by the Canadian pop punk group Sum 41. The film itself is quicker paced and flashier with some contributions by veteran Hollywood designers.

The producer of the last Godzilla film, Toho President Shogo Tomiyama, told the Asahi Shimbun. “To enhance the brand quality of Godzilla has developed over the years, we have decided to elevate Godzilla to its highest possible peak with this film and then leave it right there...The reason Godzilla has survived so long is due to its tragic themes; it’s call for peace.”

The previous two Godzilla films hadn't drawn the audiences that the producers had expected. Before his retirement Godzilla was given a star on the Walk of Fame. There are calls to raise a life-size statue of the monster in Sinagawa, the Tokyo neighborhood where Godzilla first appeared when he emerged from the sea in 1954. The end was left somewhat ambiguous, leaving open the possibility that Godzilla could come out of retirement.

Godzilla Guidebook and Museum Exhibits

“The Monster Movie Fan's Guide to Japan” (51 pages, $15 available via www.comixpress.com) by Armand Vaquer provides interesting details and facts about the sites Godzilla took in as he stomped across Japan during his five decade film career. According to to the book the moster made it as far north as Sapporo, where he destroyed the TV Tower there, and as far south as the Sakurajima volcano in Kyushu, near where he came ashore in another film. One place he didn’t visit, Vaquer told The Daily Yomiuri, was New York City, dismissing the monster in the 1998 U.S. film as GINO ("Godzilla In Name Only"). [Source: Tom Baker, Daily Yomiuri, December 24, 2010]

Tom Baker wrote in the Daily Yomiuri: “Vaquer's book tell people where to find landmarks associated not only with Godzilla, but also with his titanic terrapin counterpart, Gamera. Some of the practical information in the book is a bit dated. For instance, it has been a few years since a plane-to-terminal bus ride was a routine part of arriving at Narita Airport. Vaquer's devotion to his subject shines through in his book and also in person, but it is not uncritical devotion. In the entry on the Seto Ohashi bridge, which connects Okayama and Kagawa prefectures, he writes, "In Godzilla vs King Ghidora (1991) King Ghidora blasts the bridge (in a not-too-convincing effect) during a fly-by."

“A more positively memorable scene involved what Vaquer described in the interview as a cake-shaped cinema that stood on the site of the present-day Yurakucho Mullion building in Tokyo.” "That was in the 1954 Godzilla, where Godzilla steps on the train tracks, and the power surging through him causes his tail to whip about, and it smashes into the building. The inside joke there is that the patrons that were seeing the movie in that actual theater got to see the tail just hit the building they're sitting in watching it," he told the Daily Yomiuri.

In another part of town, the Diet Building has suffered abuse in several films, by Godzilla, Mechagodzilla, Mothra and King Kong, which must have been a cathartic experience for at least some members of the audience each time. The book includes a page about the Daigo Fukuryu Maru Exhibition Hall in Koto Ward, Tokyo, which houses the Japanese fishing boat whose 1954 irradiation by fallout from a U.S. hydrogen bomb test was a real-life reference point for the original Godzilla film.

In August 2011, a museum exhibit that featured a fishing boat exposed to nuclear fallout from the 1954 hydrogen bomb test at Bikini Atoll also featured a Godzilla display, with original script and storyboards used by the late director Ishiro Honda.

Japanese Tokusatsu Film Technique

Takashi Kondo wrote in the Yomiuri Shimbun, For decades, children have been enthralled by science fiction and superhero films and TV series, such as Godzilla, Ultraman, Gamera and Chikyu Boeigun (Global defense force), which are produced using "tokusatsu," a Japanese special effect that involves filming miniatures. Tokusatsu is being replaced by computer graphics, which means the filming technique using miniatures is in decline," Anno said. [Source: Takashi Kondo, Yomiuri Shimbun, July 6, 2012]

"The miniatures are only used when the movies and TV series are filmed," film director Hideaki Anno, curator of Tokusatsu--Special Effects Museum, Anno told thr Yomiuri Shimbun. "So they are not repaired when they break, and some are simply thrown away." Items include hero costumes, mechanical devices, and complex structures such as Tokyo Tower, the flying submarine battleship called "Goten," which appeared in the 1963 film Kaitei Gunkan (Undersea warship) and the aircraft "MAT Arrow No. 1" from the 1971 TV series Kaettekita Ultraman. The intricate designs and colors of the items is a major attraction.

Among Anno’s top five tokusatsu favorites is the original Godzilla movie of 1954. It was the first film to feature the iconic Japanese monster. Anno saw the movie just after he graduated from high school. He has praised the film as one of the greatest monster movies of all time. Unfortunately, none of the original Godzilla costumes were well preserved. The "Oxygen Destroyer," which appeared in the film as a fictional weapon of mass destruction designed to kill Godzilla, is one that survived.

Another Anno favorite comes from Mighty Jack, a science fiction espionage TV series in 1968 about a secret organization that uses the flying battleship "Mighty Jack" to fight evil, which Anno saw as a primary school student. The main attraction is the "Mighty Jack" itself, which Anno says is "extremely cool." Only 40 percent of the original battleship parts remained when the exhibition was conceived. However, it has been restored using the same techniques that were utilized to create the original.

His remaining three favorites are of the hugely popular TV Ultra series including Ultraman (1966), Ultra Seven (1967) and Kaettekita Ultraman (1971). Anno praises the series, saying, "the format of original Ultraman as a giant hero story was perfect," he said. There are numerous items on display, including an Ultraman figure used to film a flying scene, and a "color timer" attached to Ultraman's chest that shows when his energy level is depleted.

Image Sources: Wiki Commons and Japan Zone except Japan Reference (actor)

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Daily Yomiuri, Times of London, Japan National Tourist Organization (JNTO), National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated January 2013