SHAMANISM IN SIBERIA

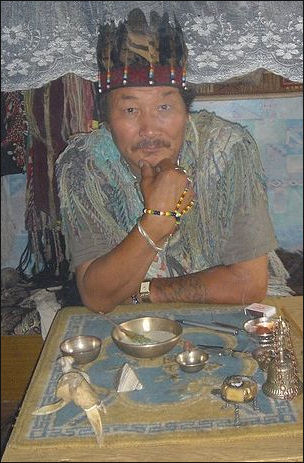

Siberian shaman Shamanism is still practiced in Russia, particularly in the Lake Baikal area of southern Siberia near the Mongolian border and in the middle Volga regions. The word Shamanism comes from Siberia. Some remote parts of Siberia don't have any restaurants, hotels or supermarket but they do have pine-plank temples known as shaman's posts where people leave offerings such money, tea, or cigarettes. Anybody who passes by without leaving an offering risks offending the evil spirits.

Shamanism practiced in Russia is divided into major sects: Buryat Shamanist east of Lake Baikal has a strong Buddhist influence; West of Lake Baikal shamanism is more Russified. The 700,000 Mari and 800,000 Udmurts, both Finno-Ugric people of the middle Volga region are shamanists.

Mongol shaman believe that humans have three souls, two of which can be reincarnated. They believe animals have two reincarnated souls which should be distrusted or else they leave human soul hungry. Prayers of reverence are always said for animals that have been killed.

David Stern wrote in National Geographic: In Siberia and Mongolia, shamanism has merged with local Buddhist traditions—so much so that it’s often impossible to tell where one ends and the other begins. In Ulaanbaatar I met a shaman, Zorigtbaatar Banzar—an outsize, Falstaffian man with a penetrating stare—who has created his own religious institution: the Center for Shamanism and Eternal Heavenly Sophistication, which unites shamanism with world faiths. “Jesus used shamanic methods, but people didn’t realize it,” he told me. “Buddha and Muhammad too.” On Thursdays in his ger (a traditional Mongolian tent) on a street choked with exhaust fumes near the city center, Zorigtbaatar holds ceremonies that resemble a church service, with dozens of worshippers listening attentively to his meandering sermons.” [Source: David Stern, National Geographic, December 2012 ]

ANIMISM, SHAMANISM AND TRADITIONAL RELIGION factsanddetails.com; ANIMISM, SHAMANISM AND ANCESTOR WORSHIP IN EAST ASIA (JAPAN, KOREA, CHINA) factsanddetails.com ; SHAMANISM AND FOLK RELIGION IN MONGOLIA factsanddetails.com

Siberian Shaman

Shaman have traditionally been important religious figures and healers among many Siberian peoples. The word “shaman” comes to us from the Tungus language via Russian. In Siberia shaman have traditionally been called upon to heal the sick, solve problems, protect groups from hostile spirits, make predictions and mediate between the spiritual world and human world and guide dead souls to the afterlife.

Cults revolving around animals, natural objects, heroes and clan leaders have also been central to the lives of many of Siberia’s indigenous people. Many groups have strong beliefs in spirits, in realms of the sky and earth and follow cults associated with animals, especially the Raven. Until fairly recently shaman were the primary religious figures and healers.

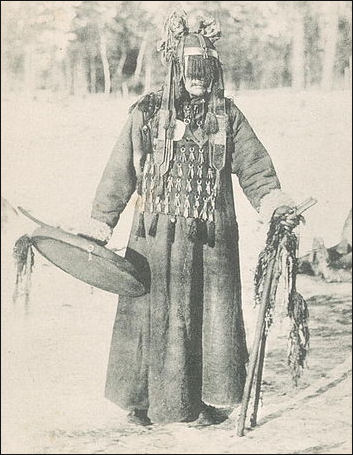

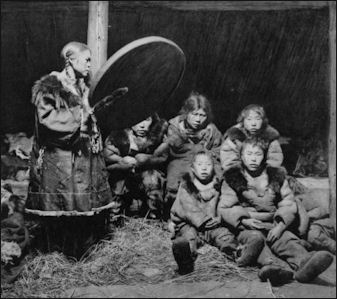

Shamanistic powers are passed on from generation to generation or by spontaneous vocation during an initiation ceremony that usually involves some kind of ecstatic death, rebirth, vision or experience. Many Siberian shaman perform their duties while dressed in a costume with antlers and beat a drum or shake a tambourines while in an ecstatic trance, regarded as reactualization of a time when people could communicate directly with the gods.

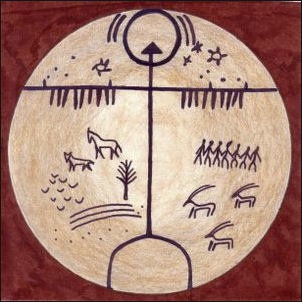

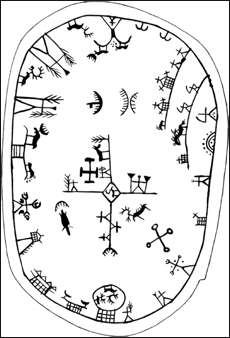

A drum is an essential tool for many Siberian shaman. It is used to call the spirts that will help the shaman and can be used as a shield to ward off evil spirits from the underworld. It is often made from wood or bark from sacred trees and skin of horses or reindeer said to have been ridden to other worlds. In a practical sense drums are used to generate hypnotic beats which help send shaman into a trance.

The Soviets tried to discredit shaman by characterizing them as greedy quacks. Many were exiled, imprisoned or even killed. Few true ones remain.

Siberian Shaman Rituals

Shaman's drum In the old days shaman often performed hip-swinging dances and did imitations of animals when they worked. Sometimes they were so effective that witnesses to their dances fell into trances and started hallucinating themselves. A Siberian shaman’s dance often has three phases: 1) an introduction; 2) a middle section; and 3) a climax in which the shaman goes into a trance or ecstatic state and wildy beats on his or her drum or tambourine.

Some Siberian shaman reportedly take hallucinogenic mushrooms to induce trances or visions. Shaman regarded plants and mushrooms as spiritual teachers and eating them is a way is taking on the properties of the spirit itself.

Many Siberia rituals have traditionally been associated with hunting and were linked with specific animals which were deeply revered, especially bears, ravens, wolves and whales. The aim of the rituals is to ensure a good hunt and this was done by honoring or giving offerings to spirits associated with the animals Many feature dancing that imitates or honors the animal in some way. There is often an element of sorrow over killing the animal.

The rituals and dances of the Eskimos, Koriak and maritime Chukchi were traditionally oriented towards the whale ad whale hunting. Often there was a festival with elements that honored each phase of the hunt. Rituals of the inland Chukchi, Evenski and Even were oriented towards reindeers and reindeer herding. Their dances often imitated the movements and habits of reindeer.

Many Siberian groups honor bears. When a bear is killed it is buried with the same reverence and rituals that accompany human burials. The eyes are covered as human eyes are. Many Arctic and Siberian people believe that bears were once humans or least have an intelligence that is comparable to that of humans. When bear meat is eaten, a flap of the tent is left open so the bear can join in. When a bear is buried some groups place it on a platform as if were a person of high status. New bears are thought to emerge from the bones of dead bears.

Beliefs About Death Among Arctic and Siberia People

Many Arctic people believe that each person has two souls: 1) a shadow soul that may leave the body during sleep or unconsciousess and take the form of a bee or a butterfly; and 2) a “breath” soul that provides life to humans and animals. Many groups believe the life forces lies within the bones, blood and vital organs. For this reason the bones of the dead are treated with great reverence so a new life can be regenerated from them. By the same token it was believed that if you ate the hearts and livers of your enemy you could absorb their power and prevent them from being reincarnated.

mythology on

Sami shaman drum After death it was believed that the breath soul left through the nostrils. Many groups seal the mouth and nostrils and cover the eyes with buttons or coins to prevent the return of the breath soul and the creation of a vampire-like state. It is believed that the shadow soul remains around for several days. A fire is kept lit by the corpse to honor the dead, , to kept evil sprits away (they preferred the dark) and to help guide the departed soul When the corpse is removed it is taken out through a back door or an unusual route to prevent the soul from returning.

Funeral Practices of Arctic and Siberia People

A large feast is held three days after the death. Many groups make wooden images of dolls of the deceased and for a period of time they are treated like the real person. They are given food and placed in positions of honor. Sometimes they are placed in the beds of wives of the deceased.

A wide variety of goods may be placed in the graves of the deceased, depending on the group. These generally includes things the deceased needs in the next life. Often totems are broken or defaced in some way to “kill” them so they don’t assist the dead in returning. Some groups decorate the grave as if it were a cradle.

Favored burial places include secluded forests, river mouths, islets, mountains and gullies. Sometimes animal sacrifices are performed. In the old days among reindeer people, the reindeer that pulled the funeral sledge was often killed. Horses and dogs were sometimes also killed. These days reindeer and other animals are considered too valuable to be used in sacrifices and wooden effigies are used instead.

In much of Siberia, because the ground is made too hard by permafrost and it is difficult to bury someone, above-ground graves have traditionally been common. Some groups placed the dead on the ground and covered them with something. Some groups place them in wooden boxes that are covered with snow in the winter and moss and twigs on the summer. Some groups and special people were buried on special platform on the trees. The Samoyeds, Ostjacks and Voguls practiced tree burials. Their platforms were placed high enough to be out of the reach of bears and wolverines.

Buryatia Shaman

Buryatia Shaman The Buryats are the largest indigenous group in Siberia. They are a nomadic herding people of Mongolian stock that practice Tibetan Buddhism with a touch a paganism. There about 500,000 Buryat today, with half in the Lake Baikal area, half elsewhere in the former Soviet Union and Mongolia. Also known as the Brat, Bratsk, Buriaad and spelled Buriat, they have traditionally lived around Lake Baikal. They make up about half the population of the Republic of Buryatia, which includes Ulan Ude and is located to the south and east of Lake Baikal. Others live west of Irkutsk and near Chita as well as in Mongolia and Xinjiang in China.

Buryat shaman are still active. Most shaman work at day jobs such as farming, construction or engineering. They are connected to the past through a chain of priests that stretches back for centuries. In the Soviet years. shamanism was repressed. In 1989 a shaman donned grotesque masks for a ceremony that hadn't been performed in 50 years.

Buryat shaman traditionally have gone into trances to communicate with gods and dead ancestors to cure diseases and maintain harmony. A Buryat shaman named Alexei Spasov told the New York Times, "You drop, your pray, you talk to god. According to the Buryat tradition, I'm here to bring some moral calmness...It's not when people are happy that they come to a shaman. It’s when they’re in need of something — troubles, grief, problems in the family, children who are sick, or they're sick. You can treat it as a sort of moral ambulance."

Buryat shaman communicate with hundreds, even thousands of gods, including 100 high-level ones, ruled by Father Heaven and Mother Earth, 12 divinities bound to earth and fire, countless local spirits which watch over sacred sites like rivers and mountains, people that died childless, ancestors and babushkas and midwives that can prevent car accidents.

See Separate Article BURYAT SHAMAN factsanddetails.com

Chukchi Shamanism

Ket shaman The Chukchi are a people who have traditionally herded reindeer on the tundra and lived in coastal settlements on the Bering Sea and other coastal polar areas. Originally they were nomads who hunted wild reindeer but over time evolved into two groups: 1) Chavchu (nomadic reindeer herders), some of whom who rode reindeers and others who didn’t; and 2) maritime settlers who settled along the coast and hunted sea animals.[Source: Yuri Rytkheu, National Geographic, February 1983 ☒]

Traditional Chukchi religion was shamanistic and revolved around hunting and family cults. Illness and other misfortunes were attributed to spirits known as “kelet” that were said to be fond of hunting humans and eating their flesh.

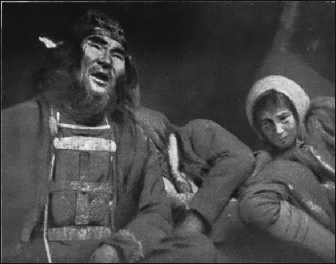

Chukchi shaman participated in festivals and small rituals performed for specific purposes. They sang and shook a tambourine while whipping themselves into an ecstatic state and use a baton and other objects for divinations. On a Chukchi shaman, Yuri Rytkheu wrote in National Geographic: "He was the preserver of tradition and cultural experience. He was meteorologist, physician, philosopher, and ideologist — a one-man Academy of Sciences. His success depended on his skill at prognosticating the presence of game, determining the route of the reindeer herds, and predicting the weather well in advance. In order to do all this , he must above all be an intelligent and knowledgeable man.” ☒

Chukchi use amulets, such as charm strings kept in a leather pouch worn around the neck, to ward off evil spirits. The inland Chukchi hold a large festival to celebrate the return of the herds to the summer grazing grounds. It is believed to that men are oppressed by evil spirits and one of the main purposes of the festival is to dispel them.

Khanty Religion and Bears

Evenk shaman costume The Khanty (pronounced HANT-ee) are a group of Finno-Ugrian-speaking, semi-nomadic reindeer herders. Also known as Ostyaks, Asiakh, and Hante they are related to the Mansi, another group of Finno-Ugrian-speaking reindeer herders. [Source: John Ross, Smithsonian; Alexander Milovsky, Natural History, December, 1993]

The Khanty believe the forest is inhabited by invisible people and spirits of animals, forest, rivers and natural landmarks. The most important spirits belong to the sun, moon and bear. Khanty shaman work as intermediaries between the living worlds and the spiritual world. The invisible people are like gremlins or trolls. They are blamed for missing puppies, strange events and unexplained behavior. Sometimes they can become visible and lure living people to the other world. This is one reason the Khanty are suspicious of stranger they meet in the forest.

The Khanty believe that women possess up to four souls, and men five. During Khanty funerals rituals are performed to make sure all the souls go to their proper places. To remove an unwanted spirit a person stands on one foot while placing a bowl of burning birch fungus under the foot seven times. In the old days sometimes horses and reindeer were sacrificed.

The Khanty believe the bear is the son of Torum, master of the upper and most sacred region of heaven. According to legend the bear lived in heaven and was allowed to move to earth only after he promised to leave alone the Khanty and their reindeer herds. The bear broke the promise and killed a reindeer and desecrated Khanty graves. A Khanty hunter killed the bear, releasing one bear spirits to heaven and the rest to places scattered around the earth. The Khanty have over 100 different words for bear. They generally don't kill bears but are permitted to kill them if they feel threatened. The Khanty walk softly in the forest so as not to disturb them.

Shaman and the Khanty Bear Festival

Kyzyl Shaman The most important ritual in Khanty life has traditionally been the ceremony that takes place after a bear is killed. Dating perhaps back to stone age, the purpose of the ceremony is to placate the bears spirit and ensure a good hunting season. The last bear festival to serve as an initiation was held in the 1930s but they have been were held in secular terms since then. Hunting bear was taboo except at these festivals.

Lasting anywhere from one to four days, these festival featured costumed dances and pantomimes, bear games, and ancestral songs about bears and the legend of the Old Clawed One. Several reindeer were sacrificed and the climax of the festival was a shaman ritual that took place during a feast with the head of the slain bear placed in the middle of the table.

Describing the shaman, Alexander Milovsky wrote in Natural History: "Suddenly Oven took up a frame drum and beat upon it, gradually increasing the tempo. As he steeped into the middle of the room, the sacrament of the ancient dance began. Oven's movements became more agitated as he entered his deep trance and 'flew' to the other world where he contacted the spirits."

Next the man who killed the bear apologized for his actions and asked the bear's head for forgiveness by bowing and singing an ancient song. This was followed by a ritual play, with actors in birch bark masks and deerskin clothes, dramatizing the role of the first bear in the Khanty creation myth.

Nanai Shaman

The Nanais live in the Khabarovsk Territory and Promotye Territory of the lower Amur basin in the Russian Far East. Formally known to Russians as the Goldi people, they are related to the Evenki in Russi and the Hezhen in China and have traditionally shared the Amur region with the Ulchi and Evenki. They speak an Altaic language related to Turkish and Mongolian. Nanai means “local, indigenous person.”

Shaman from the Nanai wore a special costume when they performed rituals. The costume was regarded as essential for their rites. For a non-Shaman to wear the costume was considered dangerous. The costume contained images of spirits and sacred objects and was adorned with iron, believed to have the power to defect blows by evil spirits, and feathers, believed to help the shaman fly to other worlds. On the costume was an image of a tree of life to which images of spirts were attached.

The Nanai believed that shaman traveled to a world tree and climbed it to reach the spirits. Their drums were said to be made of the bark and branches of the tree. The Nanai believe that spirits inhabit the upper reaches of the tree and the souls of unborn children nest on the branches. Birds linked with the idea of flight sit at the bottom of the tree. Snakes and horses are regarded as magic animals that help the shaman on his journey. Tiger spirts help teach the shaman his craft.

Selkup Shaman

Koryak shaman woman The Selkup are an ethnic group comprised of two main groups: a northern one that occupy areas on tributaries that enter the Ob and Yenisei and a southern group in the taiga. Selkup means “forest person,” a name given to them by Cossacks. The Selkup have traditionally been hunters and fishermen and often favored swampy areas rich in game and fish. They speak a Samoyedic language related to language spoken by the Nenets.

There are about 5,000 Selkups in the Yamalo-Nenets national Area. They belong to the northern groups, which has traditionally been divided into groups specialized in either hunting, fishing ro reindeer herding, with hunters having the highest rank. Fishing was done with nets or spears in dammed off areas. The southern group in nearly extinct.

The Selkup had two kinds of shaman: ones who shamanized in a light tent with a fire and ones who shamanized in a dark tent without a fire. The former inherited their ability and used a holy tree and a drum with a rattler. Both kinds were expected to be skilled storytellers and singers and were called upon to perform a new song every year at the Arrival of the Birds festival. After death, the Selkup believed, a person dwelled in a dark forest world with bears before moving on to the permanent afterlife.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, Yomiuri Shimbun, The Guardian, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated January 2012