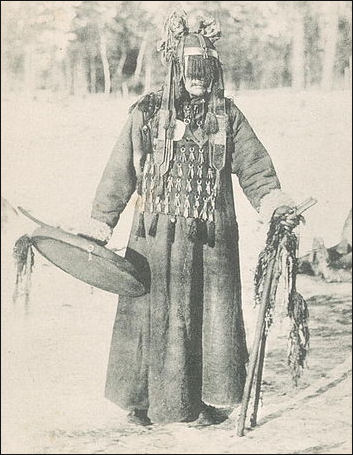

BURYAT SHAMAN

Buryatia Shaman

Buryat shaman are still active. Most shaman work at day jobs such as farming, construction or engineering. They are connected to the past through a chain of priests that stretches back for centuries. In the Soviet years shamanism was repressed. In 1989 a shaman donned grotesque masks for a ceremony that hadn't been performed in 50 years.

Buryat shaman traditionally have gone into trances to communicate with gods and dead ancestors to cure diseases and maintain harmony. A Buryat shaman named Alexei Spasov told the New York Times, "You drop, your pray, you talk to god. According to the Buryat tradition, I'm here to bring some moral calmness....It's not when people are happy that they come to a shaman. It's when they're in need of something— troubles, grief, problems in the family, children who are sick, or they're sick. You can treat it as a sort of moral ambulance."

Buryat shaman communicate with hundreds, even thousands of gods, including 100 high-level ones, ruled by Father Heaven and Mother Earth, 12 divinities bound to earth and fire, countless local spirits which watch over sacred sites like rivers and mountains, people that died childless, ancestors and babushkas and midwives that can prevent car accidents.

Buryat Religion and Folklore

The Buryat traditionally were Shamanists. Traditional beliefs still remain. Before a meal, they scatter a little bit of the food and drink as an offering to the Gods. For the Buryat white is associated with milk and good things. Silver, the white metal, is prized as an indication of wealth. The bride's dowry usually includes silver as well as coral and sheep. According to the Buryat creation myth the 11 Buryat tribes are descendants of a man and beautiful creature that was a swan by day and a woman by night, After the were married the man asked for her wings so she could no longer change into a swan. Sometime later she asked for her wings back and then flew away never to return.

Buryat, like Tibetans, adorn trees and bushes with prayer cloths. Buryat shaman are also laid to rest here. Their naked bodies are tied to a platform of trees and burned. The bleached bones and skulls of some of these shaman can still be found in the hills.

In the 17th century many Buryat converted to Tibetan Buddhism. Buddhist missionaries from Tibet and Mongolia arrived in Buryat camps at that time. In 1741, the tsarist government issued a decree recognizing the Buryats as Buddhists. Like almost all of Russia's Buddhists, the Buryats are members of the Gelupa (Yellow Hat) sect of Tibetan Buddhism, whose leader is the Dalai Lama. The Dalai Lama has visited Buryat monasteries several times.

In the 1930s, Buddhist culture was crushed. Monasteries were destroyed. Art work was given to museums. Monks were arrested. Buddhism is now experiencing a rebirth. Monasteries with dramatic upward curbing roofs, have opened and are being occupied by monks once again.

See Separate Article BURYAT factsanddetails.com

Buryat Shamanist Rituals and Vodka

Describing an elaborate ritual that began with sequence of 12 prayers to babushkas, ancestors, spirits and gods, Michael Wines wrote in the New York Times, "Relatives have prepared hard boiled eggs, cheese, mashed potatoes, pig fat and curds. They sit, smoking and drinking tea. Every one wears a hat or scarf; to go bareheaded is a serious faux pas...In the center of the room sits the beset couple, side by side, their chairs forming an 'L' with those of Mr. Spasov and a wizened family elder who has an honored seat. On the floor is a pot filled with glowing members....Next to the pot are the seven remaining bottles of Russkaya vodka and two other of uncertain lineage. Mr. Spasov drops a handful of brotherworst in the pot, and a sweet-smelling haze, not unlike marijuana drifts up to eye level and hangs. He pours vodka into a bowl, sprinkles a few drops on the embers then takes a sip himself."

Shaman in the Buryatia region and the people they help often get roaring drunk during their rituals. Vodka serves as holy water: its is sprinkled, dabbed and most of all consumed. It is not unusual for ritual to begin with 13 half-liter bottles of vodka and end with none.

Wines wrote: "’To the old babushkas,’ Spasov intones, ‘the old babushkas who died long ago, who are our saviors.’ He passed the bowl to Mrs. Montusova, who dabs a bit of vodka on each underarm and on her throat, then takes a sip herself. Along the wall, as the women make faint waggling motion with one hand, a bottle makes the rounds.

"’There are many great babushkas,’ one woman whispers. ‘And each of us has to drink his share and pray to each of them....More brotherwort, more Russkaya. More sprinkling, more shots. ‘To the old babushkas who treated children, the sons and grandsons,’ Mr. Spasov says, ‘To the old babushkas, so that those sons and grandsons never get sick.’... A roster crows. A steady procession takes shape to and from the outhouse, along planks into the thick Siberian mud."

Buryat Lawyer-Turned-Shaman

On his encounter with a Buryat shaman named Oleg Dorzhiye, David Stern wrote in National Geographic: “I met with Dorzhiyev later at his spartan, dimly lit office in the Tengeri headquarters on the outskirts of Ulan-Ude, the sedate capital of Buryatiya. Outside the low wooden building stood a huge sculpture shaped like a Christmas tree and bedecked with blue banners, moose horns, and a bear skull. [Source: David Stern, National Geographic, December 2012 ]

“Before he became a shaman, Dorzhiyev was a lawyer working for the Justice Ministry—and from his reasonable, unruffled manner, this was easy to imagine. “I wore a white shirt and necktie,” he said. “My salary was good.” Twelve years ago, when he was 34, he was struck by what’s called a “shamanic illness”—an extended period of intense psychological, professional, personal, or physical difficulties, when the spirits are thought to be sending a sign. The problems persist until the person finally relents and picks up the shamanic mantle. “My head hurt, my back hurt. Since I’m a fairly rational person, I went to a doctor,” Dorzhiyev said. But the doctor couldn’t find anything wrong. “I felt guilty, as if I were faking it.” The discomfort lasted four years, until a shaman friend entered a trance to cleanse him. During the ritual the spirits revealed that Dorzhiyev was one of the select. He has been a practicing shaman for eight years now, and the pains have ceased.

Dorzhiyev helped found Tengeri in 2003 because he wanted to feel part of a community. The organization has recently come under heavy criticism. The unspoken code is that shamans never demand money, but a number of prominent Buryat shamans have accused Tengeri’s members of charging exorbitant sums for their services and of being publicity seekers, whipping up circuslike spectacles for an impressionable public. The shamanic community, it should be said, is riven by factions and competing groups, so some of the ill will might be attributed to jealousy. “We don’t have a salary—we live on what people decide to give us,” Dorzhiyev said. While I was with him, he seemed to take his professional responsibilities very seriously, and I never saw him ask clients for money. He; his wife, Tatyana; and their two sons and a daughter live in a modest, two-room apartment in a building Tatyana manages. “We get by. We have enough for bread,” he said, laughing.

“The very idea of a shamanic organization strikes many observers as odd—heresy even—since shamans have traditionally been a rural phenomenon, working independently in their villages and nomadic tribes. Tengeri’s members counter that if they were not a registered association, they’d be overwhelmed by the mainstream religious groups that have gained a foothold since the end of communism. “Religion is marketing,” Dorzhiyev said.”

Ritual of the Buryat Lawyer-Shaman

On a ritual Dorzhiyev performed at a shaman festival, David Stern wrote in National Geographic: “Dorzhiyev, one of the shamans, hunched forward in concentration as his chanting and pounding accelerated to fever pitch. All at once he stopped and stood up. The crowd fell silent. A spirit had entered him. Dorzhiyev approached one side of the group. His headdress was like a warrior’s helmet, and his face was a murky shadow through a veil of thin black tassels. He walked slowly, mechanically, and his breathing sounded labored. People averted their gaze. “It is forbidden to look a shaman in the eyes when a spirit is in him,” said a man next to me, staring resolutely at the ground. “Bad things can happen to you.” [Source: David Stern, National Geographic, December 2012 ]

A helper brought the shaman-spirit a stool to sit on, and a crowd of about 20 people massed around him, some kneeling, others prostrating themselves on the ground. They asked him questions. Why am I unsuccessful in business? Why can’t I get pregnant? The shaman responded in a low, gravelly voice.

Later Dorzhiyev said, “As you start to fall into the trance, you feel some force of energy coming closer to you...You can’t see it—it’s like a human form in the fog. And when it comes even closer, you see who it is, that it is a spirit. Someone who lived long ago. He enters you, and your consciousness departs...Your consciousness goes to somewhere beautiful. And the spirit takes over your body. And then when you’re finished, it departs, and your consciousness returns. And you feel such a tiredness—it takes a long time for you to recover.”

Buryat Shaman Festival

David Stern wrote in National Geographic: “As shamanism’s popularity has grown, its rituals have become major events—and even big business. On an August day in a sun-drenched meadow in Russia’s Republic of Buryatiya, in Siberia, some two dozen people in indigo robes from a local shamanic group called Tengeri (Sky Spirits) performed an energetic ritual called a tailgan, in honor of a sacred spot on a nearby mountain. Clouds of gnats and the smell of boiled mutton hung in the air. The sheep had been ceremonially slaughtered and quartered and was simmering away in a massive pot. [Source: David Stern, National Geographic, December 2012 ]

“Chanting and beating on circular animal-skin drums, the shamans sat in a line facing the holy site, Bukha-Noyon, a treeless patch on the mountainside said to house holy spirits, including the male ancestor spirit of the same name. In front of them were tables bearing candles, multicolored sweets, tea, vodka, and other spirit offerings. Vendors sold buuza, succulent Buryat dumplings, from the back of SUVs, and children played in the parched grass. Above Bukha-Noyon two eagles circled—indicating, I was told, that the spirits were descending.

“I stood behind the shamans in a half circle of about 200 onlookers. The crowd was mixed: ethnic Russians, members of the local Buryat community, and a number of Westerners. Around us other shamans were also entering trances, stumbling around and holding court. The scene brought to mind a Siberian version of Night of the Living Dead.Near me, a shaman with horns on the top of his headdress channeled a spirit that chain-smoked and demanded copious amounts of vodka. Another spoke in a high-pitched voice, as if possessed by a woman. After about 20 minutes it was time for Dorzhiyev’s spirit to leave. Helpers led him a few feet away and made him jump up and down. He removed his headdress and blinked in the summer sun. Trance over.”

Shamanism and Buryat Cultural Identity

David Stern wrote in National Geographic: “Shamanism represents more than spiritual rebirth and good business. It is also a catalyst for the post-Soviet cultural revival among the native peoples of Buryatiya. On the shore of Lake Baikal, the world’s deepest body of fresh water and one of the most sacred sites in Siberia, I witnessed shamanism as self-determination—a ceremony by Buryats for Buryats. [Source: David Stern, National Geographic, December 2012 ]

“Buryats ...also practice Buddhism and Christianity. About 300 years ago the Russian Empire swallowed them in its inexorable expansion across the Eurasian landmass. During the Soviet period they, along with the region’s other indigenous groups, suffered massive population losses, and their culture was smothered. In Buryatiya today Buryats make up less than a third of the population.

With Baikal’s waters lapping just beyond a small ridge, under a sky with clouds so low it looked as if you could reach out and grab a puff, three shamans wearing green, purple, and blue robes had gathered to ask the spirits for a good harvest and for unity. They stood to the side and, almost imperceptibly, murmured invocations, sprinkling milk and vodka into a small campfire. There were no trances, no spiritual fireworks, just the whisper of prayers offered and the sizzle of liquid meeting fire.

“Next to me was Petr Azhunov, a hyperkinetic sprite of a man with a ponytail and wispy beard who is both a shaman and an anthropologist. For him shamanism is as much a political statement as a religious movement—an effort to restore a Buryat sense of nationhood after Russian hegemony. Under communism, Azhunov said, rituals like this sometimes had to be held in the dead of night. Still, many local communist officials tolerated shamanism, and some even visited shamans. “Moscow is afraid of authentic shamans like us,” Azhunov said. “Muslims are controllable, Buddhists are controllable, organized groups like the Tengeri are controllable—but real shamans cannot be controlled.” He poured to the ground an offering of a few drops of the local brew, tarasun—a pungent drink made from fermented milk—before taking a sip.

“Azhunov is a traditionalist who believes that women should be barred from certain shamanic rites. “Your photographer, Carolyn, cannot photograph this ceremony,” he said apologetically. “Women are at risk of being unclean.” The men nearby nodded gravely in agreement. A few hundred yards away at another sacred spot, Carolyn Drake and I encountered three female shamans conducting their own ritual. Their leader, Lyudmila Lozovna Lavrentiyeva, wearing a yellow scarf, red pants, and jangling necklaces, laughed at the idea that only men could be shamans. “The Buryats believe that once upon a time an eagle was flying and saw a pregnant woman sleeping under a tree and filled her with a holy spirit. She gave birth to a boy who became a shaman. So you see,” she said with evident satisfaction, “the first shaman was actually a woman.”

Image Sources:

Text Sources: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures: Russia and Eurasia, China”, edited by Paul Friedrich and Norma Diamond (C.K. Hall & Company, Boston); New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, Lonely Planet Guides, Library of Congress, U.S. government, Compton’s Encyclopedia, The Guardian, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, AFP, Wall Street Journal, The Atlantic Monthly, The Economist, Foreign Policy, Wikipedia, BBC, CNN, and various books, websites and other publications.

Last updated May 2016