SIKHS

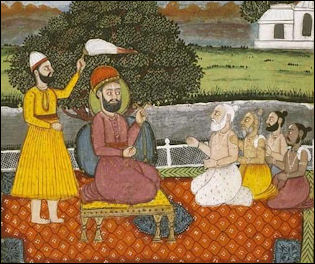

Guru Nanak with Hindu holymen The Sikhs are followers of the “Ten Gurus” (from Guru Nanak to Guru Gobind Singh) who preached monotheism, tenets found in both Islam and Hinduism, encouraged mediation and rejected the Hindu caste system. The Sikh religion (Sikhism) began in the 15th century with Guru Nanak. The word “sikh” is derived from the Sanskrit word shishya which means "disciple." In Punjabi Sikh means “learner.” Sikhs in India used the terms sikhy (“disciplineship”) and gurmat (“Guru’s doctrine”) to describe their religion.

There are about 26 million Sikhs in the world today. About 85 percent of them are in India, where they make up about three percent of population. About 95 percent of the Sikhs in India live in the Punjab, where they make up about 75 percent of population. They also live in communities scattered around India and around the world, primarily in Britain, Canada, the United States and former British colonies.

The Punjab remains the homeland of the Sikhs. Sikhs call their homeland Khalistan. Nearly all Sikhs are descendants of ancestors that were originally Hindus rather than Muslims. Many are Jats (a farming people that have a history of standing up to persecution). Until the Indian government invasion of the Golden Temple in 1984 many Sikhs didn’t even regard themselves as belonging to a distinct religious community.

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“A History of the Sikhs, Volume 1: 1469-1839 (Oxford India Collection)by Khushwant Singh Amazon.com ;

“A History of the Sikhs: Volume 2: 1839-2004" by Khushwant Singh Amazon.com ;

“Zafarnama” by Guru Gobind Singh and Navtej Sarna Amazon.com ;

“The Sikhs” by Patwant Singh Amazon.com ;

“A Critical Study of The Life and Teachings of Sri Guru Nanak Dev: The Founder of Sikhism”

by Sewaram Singh Thapar Amazon.com ;

“Sikhism: A Very Short Introduction” by Eleanor Nesbitt, Siiri Scott, et al. Amazon.com ;

“Hymns of the Sikh Gurus” by Nikky-Guninder Kaur Singh Amazon.com ;

“Shri Guru Granth Sahib, Vol. 1 of 4: Formatted For Educational Interest” by George Francis Scott Elliot Amazon.com

Sikhs and History

Sikhs understand their religious tradition in terms of Sikh history. This history and religion are of fundamental importance to Sikhs in the establishment of their a community. Traditional sources offer a grand and entertaining narrative of the history of the Sikh Gurus and their disciples since its beginning in 1469, there is little in terms of corroborative contemporary material. Even the little material that exists is often interpreted through a theological lens.[Source: Louis E. Fenech, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 3: South Asia,” edited by Paul Paul Hockings, 1992 |~|]

Louis E. Fenech, wrote in the “Encyclopedia of World Cultures”: ““It begins with the birth of Guru Nanak, who is summoned into the presence of the eternal Guru (God) and entrusted with spreading the faith. Close to death, Guru Nanak nominates as successor his disciple Lehana, who is renamed Guru Angad. This incident is related in a hymn in the scripture. Guru Angad then nominates Amar Das, who later nominates Guru Ram Das. Guru Ram Das' youngest son Arjan was then made Guru, and it was under him that the completion of Amritsar as well as the compilation of the Sikh scripture in 1604 takes place. Both of these events probably brought the Guru and his Panth under the gaze of the Mughal state. In his memoirs the emperor Jahangir reports having had the Guru arrested, beaten, and ultimately executed for his support of Jahangir's rebellious son Khusrau. Sikhs perceive this event as a martyrdom and understand it to have precipitated the doctrine of miri-piri (secularism/spirituality) in 1606 which was formulated by Guru Arjan's son, Guru Hargobind. All Sikhs, according to tradition, would from that point combine the loyalty and secular outlook of the soldier with the spirituality of the saint. |~|

“Very little information appears in Mughal sources about the seventh and the eighth Sikh Gurus, Hari Rai and Hari Krishan. For their "histories" we rely solely on a mid-nineteenth-century text popularly known as the Suraj Prakash. Executed in Delhi on 11 November 1675 by Emperor Aurangzeb, however, ensured that the history of the ninth Guru, Tegh Bahadar, would find its way into the many Persian chronicles of the emperor's reign. Guru Tegh Bahadar is understood as a martyr, upholding the righteous claims of all the dispossessed. To ensure that these claims would be maintained, the tenth Guru, Gobind Singh, instituted the Khalsa in 1699 and promulgated the Rahit recorded in the rahit-namas, with its emphasis on behavioral and sartorial Sikh observance. It was with this in hand and the ideals of the tenth Guru in mind that the Sikhs began the second decade of the eighteenth century, the Heroic Period of Sikh history.

“For Sikhs this history is a constant source of pride and honor, a fact evidenced by the large number of Sikh families who own books on Sikh history and the vast number of internet web sites devoted to the topic. The focus upon sacrifice, righteousness, and martial skill and temperament for example had certainly inspired the many Sikhs who valiantly fought in the three Indo-Pakistani wars after Independence. These traditions also guided the Sikhs during the struggle for a separate Punjabi-speaking state, a struggle that finally succeeded in 1966. |~|

Violence and Sikh History

Guarding the Golden

Temple in 1973 Although Sikhism was nonviolent in its early years, the history of the Sikhs after Gobind Singh (1666–1708), the tenth and last guru, is one of continual strife and bloodshed. In the 18th century, the Sikhs were in constant conflict with the Mughals in northern India, and bloody uprisings in the Punjab were met with equal ferocity by Muslim imperial forces. During this Heroic Period of Sikh history, .The Sikhs sacrificed life and limb in the pursuit of these righteous ideals. The Sikhs faced invasions by the Persian ruler Nadir Shah in 1738–39 and the Afghans between 1747 and 1769.

This sacrifice hardened the Khalsa and eventually culminated in 1799 with the first-ever Sikh kingdom, the Lahore Darbar, under the celebrated Maharaja Ranjit Singh, (1780-1839), who established a strong Sikh state in the Punjab region, which spanned from the Sutlej River to Kashmir. This was the highest point of Sikh power and prestige in northern India. [Source: D. O. Lodrick, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life”, Cengage Learning, 2009 *]

After the death of Ranjit Singh, the Sikh kingdom quickly disintegrated, leading to the annexation of Punjab by the British in 1849. Almost a century of stability followed until the partition of British India in 1947, which resulted in violent outbreaks in Punjab. Around 2.5 million Sikhs fled from the western regions of Punjab, which were to become part of Pakistan, and resettled in India. During the creation of the independent states of India and Pakistan, communal strife arose, leading to violence between Hindus, Sikhs, and Muslims. It is estimated that one million people lost their lives while attempting to cross the newly formed borders. *\

Guru Nanak

Guru Nanak (1469-1539) is credited with founding the Sikh religion in an attempt to come up with a religion that harmonized Islam and Hinduism and contained the good points of each religion but not their inequalities. Sikhism emerged as a distinct religion because of Guru Nanak's personal rejection of pilgrimages, his stress on living the good life on earth, and his appointment of a successor as the master (guru ) for his disciples (sikhs).

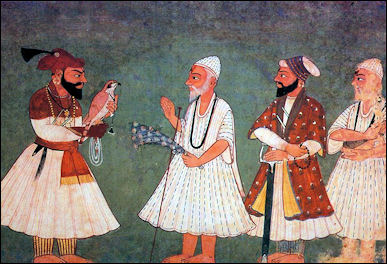

Guru Gobind Singh meets Guru NanakNanak Dev Ji ( Guru Nanak) was born in Talwandi (now Nankana Sahib), a Punjabi village in what is now in Pakistan, 50 kilometers (30 miles) southwest of Lahore, . Guru Nanak was a khatri, a largely mercantile caste within the kshatriya caste. His father was a civil servant, and it is presumed he grew up in a middle-class family In 1499, according to Sikh belief, 30-year-old Nanak took a swim in the nearby Bein River and did not resurface for three days. When he reappeared, he said that he had had a revelation and was deeply moved by an experience with God. He famously proclaimed, "There is no Hindu, there is no Muslim" and said he wanted to offer the people a new religion that combined the best parts of these and other faiths.

During the experience Guru Nanak said he was given a cup of sweetened, sacred water called amrit (literally “undying,” the nectar of immortality) and told by God: “Nanak, this is the cup of Devotion of the Name: drink this...I am with you, and I bless you and exalt you. Whoever remembers you will receive my blessing. Go, rejoice in my name and tell others to do the same. I am bestowing on you the gift of my Name. Let this be you vocation.” After meditating for three days Nanak gave away all of his possessions and announced "whose path shall I follow? I shall follow the path of God," implying there was only one true god and he accepted all people.

Guru Nanak began traveling, mainly to pilgrimage centers. He visited both Muslim and Hindu shrines proselytizing his belief and attracted a great many followers. He reportedly traveled as far east as Assam, as far north as Ladakh and as far south as Sri Lanka and made a pilgrimage to Mecca and Medina. Poetry was his medium of expression. At the heart of his message was a philosophy of universal love, devotion to God, the singularity of the ultimate reality and the consequent unity of humanity. and the equality of all men and women before God. He set up congregations of believers who ate together in free communal kitchens in an overt attempt to break down caste boundaries based on food prohibitions. As a poet, musician, and enlightened master, Nanak's reputation spread, and by the time he died he had founded a new religion of "disciples" (shiksha or sikh) that followed his example. [Source: Library of Congress]

See Separate Article GURU NANAK: factsanddetails.com

Ten Gurus

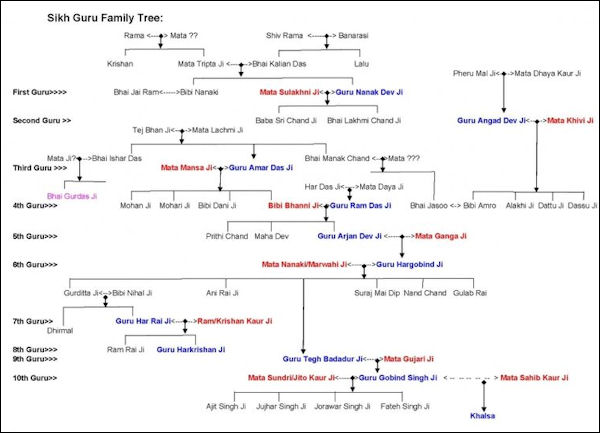

Nanak's son, Baba Sri Chand, founded the Udasi sect of celibate ascetics, which continued in the 1990s. However, Nanak chose as his successor not his son but Angad, his chief disciple, to carry on the work as the second guru. Thus began a lineage of teachers that lasted until 1708 and amounted to ten gurus in the Sikh tradition, each of whom is viewed as an enlightened master who propounded directly the word of God. Angad developed the Gurmukhi script in which to record Nanak's life and doctrine.

Guru Arjun Dev being pronounced fifth guruThe Ten Gurus are:

1) Guru Nanak (1469–1539)

2) Guru Angad (1504–1552)

3) Guru Amar Das (1479–1574)

4) Guru Ram Das (1534–1581)

5) Guru Arjan (1563–1606)

6) Guru Hargobind (1595–1644)

7) Guru Har Rai (1630–1661)

8) Guru Har Kishen (1656–1664)

9) Guru Tegh Bahadur (1621–1675)

10) Guru Gobind Singh (1666–1708)

The third guru, Amar Das fixed Sikh funeral and marriage rites, forbade intoxicants and cruel Hindu customs, and established 22 centers of worship and missionary centers to spread the message. He was so well respected that the Mughal emperor Akbar visited him . Amar Das appointed his son-in-law Ram Das (1534-81) to succeed him, establishing a hereditary succession for the position of guru. He also built a tank for water at Amritsar in Punjab, which, after his death, became the holiest center of Sikhism.

The Ten Sikh Gurus are more than just “spiritual counselors,” the traditional definition of gurus; they are Sat Gurus, “true teachers” who reveal God’s teachings. Their succession has been compared to the transfer of a flame from one spiritual unifier to another. By the late sixteenth century, the influence of the Sikh religion on Punjabi society was coming to the notice of political authorities. Ram Das was the fourth Sikh guru. He founded the city of Armistar, which was built on land given by the Mughal emperor Akbar. The fifth guru, Guri Arjun was Ram Das’s son. He built the original Golden Temple and compiled the Adi Granth (First Book), the canon of hymns and sayings of Guru Nanak and his successors, to be revered by the Sikhs. Guru Arjun was tortured and killed in Lahore by the Mughal Emperor Jahangir in 1606 for alleged complicity in a rebellion. He was an acclaimed poet like Guru Nanak. In response to Ram Das's execution the next guru, Hargobind (d. 1644), militarized and politicized his position and fought three battles with Mughal forces.

See Separate Article on TEN GURUS OF SIKHISM: factsanddetails.com

Guru Gobind Singh and Sikh Militarism

Guru Gobind Birthplace Guru Gobind Singh (1666-1708) was the tenth and last Guru. He is regarded as the second most important guru after Guru Nanak.. He became guru after his father, the Ninth Guru Tegh Bahadur was beheaded for refusing to convert to Islam. Four of Guru Gobind Singh’s sons died fighting for Sikh rights. One was killed in a battle against the Mughals. Another was bricked up alive in wall for refusing to renounce his faith. Gobind Singh himself died a few days after being struck by an assassins arrow.

Guru Nunak was a pacifist. Guru Gobind Singh responded to Mughal oppression by transforming the Sikhs into a unit of fighters and a militant brotherhood dedicated to defense of their faith at all times, ready to challenge Mughal rulers and the Hindu caste system. He glorified martyrs who he said “attain glory both here and hereafter” and instituted a baptism ceremony involving the immersion of a sword in sugared water that initiates Sikhs into the Khalsa (khalsa , from the Persian term for "the king's own," often taken to mean army of the pure) of dedicated devotion.

Guru Gobind Singh is responsible for the "Five Ks" and the turbaned appearance of Sikh males. He introduced the custom of carrying a large curved dagger in a silver sheath, wearing a turban, carrying a comb and never cutting the hair or beard. In 1699 by he founded a militant fraternity called Khalsa (meaning "pure" or “God elect”). He assembled five trusted lieutenants (called panj piyarey, the five beloved ones") in Anandpur Sahib ("town of bliss") to energize Sikhism in the face of Muslim invasions.

The "Five Ks"—uncut hair (kesh ), a long knife (kirpan ), a comb (kangha ), a steel bangle (kara ), and a special kind of breeches not reaching below the knee (kachha )—were expected to be observed at all times. Male Sikhs took on the surname Singh (meaning lion), and women took the surname Kaur (princess). All made vows to purify their personal behavior by avoiding intoxicants, including alcohol and tobacco. In modern India, male Sikhs who have dedicated themselves to the Khalsa do not cut their beards and keep their long hair tied up under turbans, preserving a distinctive personal appearance recognized throughout the world. [Source: Library of Congress *]

Under Guru Gobind Singh military and political doctrine became very important to the Sikhs. The Khalsa brotherhood merged "religious, military and social duties” into “a single discipline." The Sikhs have a tradition of being both militarily trained and militarily prepared. This tradition helps explains how the religion has survived intense persecution and why Sikhs recruited by the Indian, Pakistani and British militaries.

Much of Guru Gobind Singh's later life was spent on the move, in guerrilla campaigns against the Mughal Empire, which was entering the last days of its effective authority under Aurangzeb (1658-1707). After Gobind Singh's death, the line of gurus ended, and their message continued through the Adi Granth (Original Book), which dates from 1604 and later became known as the Guru Granth Sahib (Holy Book of the Gurus). The Guru Granth Sahib is revered as a continuation of the line of gurus and as the living word of God by all Sikhs and stands at the heart of all ceremonies. *

Sikhs After the Tenth Guru

The Ten Guru Sikh institution established after Guru Nanak's death in 1539 lasted until shortly after the death of the Tenth Guru, Gobind Singh in 1708. In the tumultuous 18th century, a Sikh kingdom arose and then dissolved into several feudal states and the Sikhs became a confederation of warrior tribes.

Bhatts of Guru Granth Sahib

By the mid 18th century, Sikh guerillas challenged the Mughal overlords and contributed to the collapse of Mughal administration in the Punjab. They also helped keep Afghan invaders out when they invaded India between 1747 and 1769. One of the most famous Sikh heros was Baba Deep Singh. During a battle to save the Golden Temple from desecration he reportedly had his head cut off but kept right on fighting with a sword in one hand and his head in the other.

Maharajah Ranjit Singh, the "Lion of Punjab," ruled over all of the Punjab from Lahore in the early 19th century. He emerged as leader at the end of the 18th century and remained the Sikh leader until his death in 1839. After he died the political side of Sikhism fell into decline. The last Sikh king, Maharajah Dhulip Singh, adopted Christianity and gave the largest diamond in the world at that time, the Koh-i-nur, to Queen Victoria.

The British viewed the Sikhs as a martial race and actively recruited them beginning in the mid 19th century for their military forces in India. Sikhs also served in the British military abroad. The exposure of these Sikh soldiers to the outside world launched the first waves of Sikh emigration, to Britain and to British colonies in Malaysia, Burma, Africa and other places.

Sikhs in the Early Twentieth Century

Revivalist movements of the late nineteenth century centered on the activities of the Singh Sabha (Assembly of Lions), who successfully moved much of the Sikh community toward their own ritual systems and away from Hindu customs, and culminated in the Akali (eternal) mass movement in the 1920s to take control of gurdwaras away from Hindu managers and invest it in an organization representing the Sikhs. The result was passage of the Sikh Gurdwara Act of 1925, which established the Central Gurdwara Management Committee to manage all Sikh shrines in Punjab, Haryana, and Himachal Pradesh through an assembly of elected Sikhs.

The combined revenues of hundreds of shrines, which collected regular contributions and income from endowments, gave the committee a large operating budget and considerable authority over the religious life of the community. A simultaneous process led to the Akali Dal (Eternal Party), a political organization that originally coordinated nonviolent agitations to gain control over gurdwaras , then participated in the independence struggle, and since 1947 has competed for control over the Punjab state government. The ideology of the Akali Dal is simple — single-minded devotion to the guru and preservation of the Sikh faith through political power — and the party has served to mobilize a majority of Sikhs in Punjab around issues that stress Sikh separatism.

Leaders of sects and sectarian training institutions may feel free to issue their own orders. When these orders are combined with the prestige and power of the Central Gurdwara Management Committee and the Akali Dal, which have explicitly narrow administrative goals and are often faction-ridden, a mixture of images and authority emerges that often leaves the religion as a whole without clear leadership. Thus it became possible for Sant Jarnail Singh Bhindranwale, head of a training institution, to take effective control of the holiest Sikh shrine, the Golden Temple in Amritsar, Punjab, in the early 1980s.

Guru family tree

Sikhs and the Partition of India and Pakistan in 1947

When Indian independence finally came after World War II the Punjab was divided between the largely Hindu state of India and the largely Muslim state of Pakistan in 1947. Despite Sikh protests, the partition of the Indian subcontinent divided their homeland. Violence erupted between Sikhs and Muslims as Pakistani Sikhs fled to India and Indian Muslims fled to Pakistan. Militant Sikhs and Hindu Jats fought the Muslims of Punjab in a struggle that resulted in over a million casualties. Some 2.5 million Sikhs migrated from West Punjab (in Pakistan) into East Punjab (in India).

The partition of India and Pakistan was the largest migration of people in recorded history and the Punjab where the Sikhs had traditionally lived was the center of it: Hindus, Muslims, and Sikhs who found themselves on the "wrong" side of new international boundaries traveled to the other side to be with their own kind. After partition, between 12 and 15 million Hindus, Sikhs and Muslims migrated from their homelands to live with people of the same religion. Millions of Muslims trekked to West and East Pakistan while millions of Hindus and Sikhs headed in the opposite direction. Many hundreds of thousands never made it. [Source: William Dalrymple, The New Yorker, June 29, 2015]

The greatest upheaval occurred in the Punjab, where the border was drawn between the region’s two largest cities: Lahore and Amritsar. Millions of Sikhs and Hindus in Pakistani Punjab migrated to India and millions of Muslims migrated to Pakistan. In the east in Bengal Muslims migrated to East Pakistan (present-day Bangladesh) and Hindus migrated into India. Christians, Parsis, Buddhists, Jews are people of other religions largely stayed where they were and were spared the mass dislocation and violence that affected the Muslims, Sikhs and Hindus. Millions of Sikhs were forced to leave their ancestral homeland in the West Punjab.

Impact of the Partition of India and Pakistan in 1947 on the Sikhs

The partition of India and Pakistan made Sikhs the majority in rural areas of central Indian Punjab. Before partition in 1947 Sikhs made up only 13 percent of undivided Punjab in what is now Pakistan and India. After partition most of the Muslims left in Indian Punjab fled to Pakistan and many of the Hindus living in Pakistani Punjab moved somewhere else in India other than Indian Punjab, while Sikhs in Pakistani Punjab fled to Indian Punjab, creating the huge concentrations of Sikhs there that remain there to this day.

Partition produced 24 million refugees and left 200,000 to 1 million people dead. Prior to partition Lahore, a city with 1.2 million people contained 500,000 Hindus and 100,000 Sikhs. Only a handful remained after partition. The division of the Punjab, where much of the violence took place, was not announced until two days after independence in part so the British could escape and not be held responsible for the violence that was destined to follow. No preparations had been made so once the violence got going there was little to stop it.

Rama Lakshmi wrote in the Washington Post: “Every year in March, Bir Bahadur Singh goes to the local Sikh shrine and narrates the grim events of the long night six decades ago when 26 women in his family offered their necks to the sword for the sake of honor. At the time, sectarian riots were raging over the partition of the subcontinent into India and Pakistan, and the men of Singh's family decided it was better to kill the women than have them fall into the hands of Muslim mobs. "None of the women protested, nobody wept," Singh, 78, recalled as he stroked his long, flowing white beard, his voice slipping into a whisper. "All I could hear was the sound of prayer and the swing of the sword going down on their necks. My story can fill a book." [Source: Rama Lakshmi Washington Post, March 12, 2008]

See Separate Articles: PARTITION OF INDIA AND PAKISTAN factsanddetails.com ; VIOLENCE AFTER THE PARTITION OF INDIA AND PAKISTAN factsanddetails.com

Sikh Separatist Movement

Frustrations over discrimination led to the creation of a Sikh militancy in the 1970s that demanded a separate Sikh state. The government didn’t want the Punjab — the breadbasket of India — to break away from India.. Using a argument similar to that used later in Kashmir, the Indian government argued that if the Sikhs were allowed to have their own state then other ethnic and religious groups would also want autonomy, potentially fracturing India into a bunch of small states like the Balkans.

The leader of the Sikh separatist movement was Jarnail Singh Bhindranwale, a charismatic preacher who wore a blue turban tied in the old tradition way, had powerful hands, a droopy left eyelid and crooked yellowish teeth. He often carried a arrow in his hand which symbolized his religious authority. During his inflammatory and virulent speeches, he accused Hindus of injustice and described how police tortured Sikhs by cutting open their legs and pouring salt in their wounds. He demanded that Punjab be made a Sikh state called Khalistan. It was hard to imagine this happening since the Punjab grew two thirds of India's grain.

Problems between Sikhs and the Indian government escalated in the small village of Dheru in 1981 when two Bhindranwale followers, who were also fugitives, were cornered by authorities and escaped after shooting two policemen dead. Later Bhindranwale was arrested after a gun battle for his involvement with the murder of the police. That same day three Sikhs on motorcycles shot into a crowd of Hindu's, killing four.

See Separate Article: SIKH SEPARATIST MOVEMENT factsanddetails.com

Attack of the Golden Temple and Assassination of Indira Gandhi

After Bhindranwale was released for lack of evidence he holed himself up in the Golden Temple in Amritsar, Sikhdom's holiest site, with perhaps a thousand supporters armed with AK-47s, mortars and rockets. While he was in the temple one of his militants was killed by a woman. Bhindranwale boasted the death would be avenged in less than 24 hours. Soon after the body of the woman was found with her breasts and genitals burned and her arms and legs crushed. An accomplice of hers was found sliced in seven different pieces. [Source: "The Villagers" by Richard Critchfield, Anchor Books]

In May 1984 Indian army infantrymen attacked the Golden Temple when more than a thousand of pilgrims and militants were inside. Indian soldiers and Sikh militants exchanged mortar and machine gun fire. Seven Indian tanks shelled the temple’s three story tower where Bhindranwale was thought to be hiding out. When the fighting stopped the Golden Temple was in ruins. Between five hundred and two thousands civilians, Sikh militants and Indian soldiers were killed and many of the Sikh's holiest scriptures, some handwritten by the ten Gurus themselves, had been reduced to ashes. Bhindranwale was found dead with one eye open and one eye closed.

In 1984, two Sikhs that were trusted bodyguards assassinated Prime Minister Indira Gandhi. Thousands of Sikhs were killed in riots that followed the assassination. The bodyguards apparently committed the murder in revenge for the assault on the Golden temple in Amritsar which had taken place five months before. They were reportedly given a "black warrant," or execution order, by Sikh militant leaders.

See Separate Article: SIKH SEPARATIST MOVEMENT factsanddetails.com

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: “World Religions“ edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “Encyclopedia of the World’s Religions“ edited by R.C. Zaehner (Barnes & Noble Books, 1959); “Encyclopedia of the World Cultures: Volume 3 South Asia” edited by David Levinson (G.K. Hall & Company, New York, 1994); “The Creators “ by Daniel Boorstin; National Geographic, the New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Times of London, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated December 2023