GURU NANAK

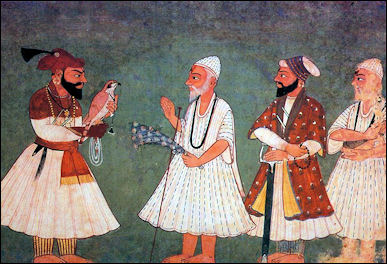

Guru Gobind Singh meets Guru Nanak 170 years after his death

Guru Nanak (1469-1539) is credited with founding the Sikh religion in an attempt to come up with a religion that harmonized Islam and Hinduism and contained the good points of each religion but not their inequalities. Sikhism emerged as a distinct religion because of Guru Nanak's personal rejection of pilgrimages, his stress on living the good life on earth, and his appointment of a successor as the master (guru ) for his disciples (sikhs ).

Sikhism is rooted in the religious experience, piety, and culture of Guru Nanak. Many pf his idea originated from inner revelation but were influenced by the contemporary religious environment of his day — particularly the devotional tradition of the medieval Sufi sants ("poet-saints") of North India, with whom he shared certain similarities. He established a foundation of teaching, practice, and community from which to express his own religious ideals. He is said to have had an especially strong sense of mission, compelling him to proclaim his message. His disciples were known as sikhs, or "learners." [Source: Pashaura Singh, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Religious Practices”, Thomson Gale Sikhism, 2006]

Most of the details of Guru Nanak's life come from a body of hagiographic literature called the Janamsakhis ((Janam-Sakhis, Birth Narratives or Life Testimonies), which appeared a century and a half after Nanak's death and continued to expand for some time until printed editions were produced in the nineteenth century. Sikhs today rely primarily on the accounts given in the Puratan Janamsakhi, which explains four major cycles in Nanak's life story: 1) his early contemplative years; 2) his religious revelation and enlightenment; 3) his years of travel and teaching; and 4) his later life and establishment of a religious community. .[Source: Arvind-Pal S. Mandair, “Encyclopedia of India”, Thomson Gale, 2006]

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“A History of the Sikhs, Volume 1: 1469-1839 (Oxford India Collection)by Khushwant Singh Amazon.com ;

“A History of the Sikhs: Volume 2: 1839-2004" by Khushwant Singh Amazon.com ;

“Zafarnama” by Guru Gobind Singh and Navtej Sarna Amazon.com ;

“The Sikhs” by Patwant Singh Amazon.com ;

“A Critical Study of The Life and Teachings of Sri Guru Nanak Dev: The Founder of Sikhism”

by Sewaram Singh Thapar Amazon.com ;

“Sikhism: A Very Short Introduction” by Eleanor Nesbitt, Siiri Scott, et al. Amazon.com ;

“Hymns of the Sikh Gurus” by Nikky-Guninder Kaur Singh Amazon.com ;

“Shri Guru Granth Sahib, Vol. 1 of 4: Formatted For Educational Interest” by George Francis Scott Elliot Amazon.com

India and the Punjab at the Time of Guru Nanak

Guru Nanak grew up at a time when rivalry between Hindus and Muslims was common, the Mughal Empire was emerging and various Hindu movement were advocating a love of god that transcended religious conflict Sikhism originated in the Punjab region of northwestern India when many religious teachers, known as "Sants," were seeking to reconcile the two opposing dominant faiths, Hinduism and Islam. The Sants expressed their teachings in vernacular poetry based on inner experience.

Sikhism originated in the early 16th century when Muslims were beginning to take control of northern India and The Punjab. In the early 13th century, a Turkish slave dynasty defeated the Ghuids in India and established the Sultanate of Delhi (1210-1526).. It ruled the whole of the Ganges Valley, consolidated Turkish power and lasted for 300 years until the arrival of the Mughals. The Delhi Sultanate refers to the various Muslim dynasties that ruled in India. Both the Quran and sharia (Islamic law) provided the basis for enforcing Islamic administration over the independent Hindu rulers

The Mughal empire was founded in 1526 by Zahir-ud-Din Babur (1483-1530, ruled 1526-1530), a Muslim chieftain from Central Asia who defeated the last Delhi sultan and established the Mughal Empire. Babur was described by one writer as a "marvelous writer, brilliant statesman and ruthless general.. He initially established his rule in Kabul in 1504 and later became the first Mughal ruler (1526-30). Babur’s determination was to expand eastward into Punjab, where he had made a number of forays. At its height, Babur's empire occupied what is now eastern Afghanistan, part of northern Pakistan, the Punjab and part of northern India south of the Himalayas and around the Ganges.

Early Life Life of Guru Nanak

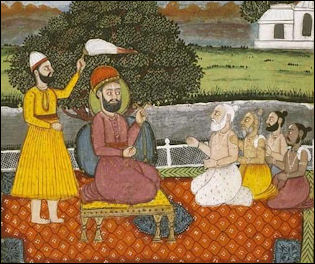

Guru Nanak with Hindu holymen Nanak Dev Ji ( Guru Nanak) was born in 1469 into a Hindu family in Talwandi (now Nankana Sahib), a Punjabi village in what is now in Pakistan, 64 kilometers (40 miles) southwest of Lahore, to Mehta Kalu and Tripta. Nanak was a khatri, a largely mercantile caste within the upper kshatriya caste. His father was a civil servant, and it is presumed he grew up in a middle-class family

It is said Nanak was acclaimed by Muslims and Hindus alike as a future religious leader. There are stories that were were signs of divinity around him from the start, such as the time a cobra was found rearing over his head — not to attack him, but to shade him from the sun as he napped. Vinay Lal, wrote: As is quite common in the accounts furnished of the founders of major religions or religious movements, his birth is said to have been accompanied by auspicious signs, and the family pandit is described as having declared that Nanak would become a great prophet. The little boy was named Nanak after his sister Nanki, and in childhood he is said to have had a sonorous voice, which brought him to the attention of Rai Bular, the Muslim landlord on whose land Nanak’s father worked. In his childhood, Nanak is said to have been precocious; but as he was thought to be an idler in his adolescence, who brought neither fame nor profit to his father, it was suggested that he be married off...And so Nanak’s parents resorted, in 1485, to the practice still commonly encountered in Indian families to turn boys into responsible fathers, and so make men of them. [Source: Vinay Lal, professor of history, UCLA ==]

From an early age, Nanak was exposed to a variety of religious beliefs, including Hinduism and Islam, and later gained a reputation for questioning those beliefs. As a teenager, he worked as a herder and married at the age of 12. His wife Sulakhani joined him at age nineteen and they had two sons Sri — Chand and Lakhmi Das. Later he moved to the city of Sultanpur, where he held an administrative job for the region's governor. Being a member of the kshatriya (warrior) caste, he worked very hard at his job but his mind was often elsewhere and he spent long hours of each morning and evening in meditation and devotional singing. [Sources: Arvind-Pal S. Mandair, “Encyclopedia of India”, Thomson Gale, 2006; World Religions Reference Library, Thomson Gale, 2007]

Nanak had a hard time finding a profession that suited him. He also worked as a trader, but seemed to be mainly preoccupied with spiritual concerns, and sought out the company of holy men and ascetics. While Nanak was working as a storekeeper in the state granary and after working there for several years he quit after being falsely accused of embezzlement and vowed to forsake the worldly life. On one journey from home to gain religious knowledge, Nanak encountered Kabir (1440-1518), a saintly figure who was revered by the followers of many religious traditions. Later Nanak and his closest associate, a Muslim bard named Mardana, organized regular nightly singing of devotional hymns that ended with a bath at dawn in the Bein River

Guru Nanak's Great Revelation

In 1499, according to Sikh belief, 30-year-old Nanak took a swim in the Bein River after the regular singing sessions and underwent his first major mystical experience, in which he received a calling to teach people a path of devotion to the divine

In one telling of the story he went underwater and disappeared without leaving a trace. Family members gave him up for dead. Finally, he resurfaced after three days. When he reappeared, he said that he had had a revelation and was deeply moved by an experience with God. He famously proclaimed, "There is no Hindu, there is no Muslim" and said he wanted to offer the people a new religion that combined the best parts of these and other faiths. [Source: Pashaura Singh, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Religious Practices”, Thomson Gale 2006]

During the experience Guru Nanak said he was given a cup of sweetened, sacred water called amrit (literally “undying,” the nectar of immortality) and told by God: “Nanak, this is the cup of Devotion of the Name: drink this...I am with you, and I bless you and exalt you. Whoever remembers you will receive my blessing. Go, rejoice in my name and tell others to do the same. I am bestowing on you the gift of my Name. Let this be you vocation.” After meditating for three days Nanak gave away all of his possessions and announced "whose path shall I follow? I shall follow the path of God," implying there was only one true god and he accepted all people.

Pashaura Singh wrote in the “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Religious Practices”: His statement “no Hindu, no Muslim”, made during the declining years of the Lodhi sultanate, must be understood in the context of the religious culture of the medieval Punjab. The two dominant religions of the region were the Hindu tradition and Islam, both making conflicting truth claims. To a society torn with conflict, Nanak brought a vision of a common humanity and pointed the way to look beyond external labels for a deeper reality. After his threeday immersion in the waters — a metaphor of dissolution, transformation, and spiritual perfection — Nanak was ready to proclaim a new vision for his audience. [Source: Pashaura Singh, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Religious Practices”, Thomson Gale 2006]

In one of his own hymns in the Adi Granth, the Sikh scripture, he proclaimed, "I was a minstrel out of work, the Lord assigned me the task of singing the divine Word. He summoned me to his court and bestowed on me [the] robe of honoring him and singing his praise. On me he bestowed the divine nectar [amrit] in a cup, the nectar of his true and holy Name" [Source: Adi Granth, p. 150]

Guru Nanak Travels Widely and Spreads His Message

Although Nanak was a married man with two sons, he decided to abandon his life of a householder and became an itinerant preacher. He identifyied himself as neither Muslim or Hindu and was accompanied by his childhood friend Mardana on his travels. In Saidpur village, Nanak gained his first disciple, the carpenter Lalo, with whom he shared a basic house. [Source: Vinay Lal, professor of history, UCLA ==]

Guru Nanak began traveling, mainly to pilgrimage centers. He visited both Muslim and Hindu shrines proselytizing his belief and attracted a great many followers. He reportedly traveled as far east as Assam, as far north as Ladakh and as far south as Sri Lanka and made a pilgrimage to Mecca and Medina.

According to the Puratan Janamsakhi, Nanak spent the twelve years traveling. He sought out both Hindu and Muslim places of pilgrimage and came into contact with the leaders of different faiths and tested the strength and veracity of his own ideas in religious discussions. He ventured as far eastward to Banaras (Varanasi), Bengal, Assam and Orissa, southward to Tamil Nadu and Sri Lanka, northward to Kashmir, Ladakh and Tibet, and finally westward to the Muslim regions, reaching Mecca, Medina, and Baghdad.

Poetry was his medium of expression. He set up congregations of believers who ate together in free communal kitchens in an overt attempt to break down caste boundaries based on food prohibitions. As a poet, musician, and enlightened master, Nanak's reputation spread, and by the time he died he had founded a new religion. [Source: Library of Congress]

Stories from Guru Nanak’s Travels

Vinay Lal wrote: “As Nanak roamed over the Punjab and north India, he rapidly began to acquire disciples or shishya, from which the word ‘Sikh’ was ultimately derived. Nanak spoke of the dignity of labor, and one of the first stories that began to circulate about him concerned his interaction with Malik Bhago, the zamindar of Saidpur village. Nanak refused the hospitality of his home, and when asked to explain his conduct, it is said that he took out a dry crust of bread from his pocket that he had brought from Lalo’s home. When he squeezed the sweets that Bhago had placed before him, it is said that drops of blood fell from the sweets; but when he squeezed the piece of bread, drops of milk fell forth. The moral of this story could not have been lost on Bhago, or on Nanak’s contemporaries, but the cynic who is witness to the late twentieth-century, where immense fortunes are made with the twinkling of an eye, and affluence has little or no relation to the true fruits of one’s labor, might well wonder whether Bhago was as contrite as Nanak’s hagiographies suggest. In the event, it is possible to view Guru Nanak as an early spokesperson of working class people, and to view the revolt he lead not only as a form of dissent against the oppressions of caste and religion, but as a form of class awakening.[Source: Vinay Lal, professor of history, UCLA ==]

“Nanak’s teachings are best understood against the backdrop of bhakti, the devotional movement which was then sweeping north and western India, and in the context of the ossification of both Hinduism and Islam into religious faiths which inculcated blind beliefs in their followers. During the course of his travels, Nanak reached Hardwar, where he encountered Brahmins who, while standing in the Ganga, were throwing water towards the sun to appease the souls of their ancestors. It is reported that Nanak bent down and began throwing water in the opposite direction, and when asked what he was doing, he replied that he was watering his fields in the Punjab. When his reply was met with derision, Nanak reportedly told the Brahmins that if the water they were sprinkling could reach the sun, then doubtless the water could also reach his fields, which were merely a few hundred miles away. Similarly, Nanaks’s travels took him to Mecca. When he arrived in the city, exhausted and hungry, Nanak lay down, and was rudely awaken by a Muslim priest, who asked how Nanak had dared to sleep with his feet pointing towards the Kaaba. Nanak’s rejoinder, whereby he invited the Kazi to turn his feet wherever God could not be found, is said to have left the Kazi speechless. [Source: Vinay Lal, professor of history, UCLA ==]

Guru Nanak Forms a Religious Community

In the 1520s, when Nanak was around 50 he settled on the banks of the river Ravi in western Punjab, bought some land there and formed a community made up mainly of farmers, artisans and traders in Kartapur (Creator's Abode) in present-day Pakistan that empathized devotion and meditation not rituals. He spent his days bathing in the morning, followed by worship, and enjoyed a communal meal in the evening. Although Nanak frowned upon stories of miracles many stories grew up about miracles he performed such as bringing to life a dead tree and squeezing blood from a rich man’s food. Nanak He composed 974 hymns, mainly aimed at expressing the name of God, which became the basis of the Sikh holy book, the Guru Granth.

Nanak lived in Kartapurfor the rest of his life as the "spiritual guide". His charisma and teaching attracted many people. The first community of Nanak's disciples — those who chose to follow him as their Guru (divine teacher) — was composed primarily of former Hindus. These disciples called themselves "shiksha" or "sikh" ("Sikhs" (followers and followed his example.

At Kartarpur, Nanak led his community of disciples, instructing them in spiritual practice and study. "Nam Simaran" (remembrance of the Name) and Kirtan (singing hymns of praise) were regular features of devotion. At the same time he insisted that his disciples remain fully involved in worldly affairs by doing practical labor (Nanak himself tended his own crops) while maintaining a regular family life. [Source: Arvind-Pal S. Mandair, “Encyclopedia of India”, Thomson Gale, 2006]

Nanak conveyed his message of liberation through eloquent poems and religious hymns. His followers used the hymns in devotional singing (kirtan) in worship. The first Sikh families that formed the community around Guru Nanak in the early decades of the sixteenth century formed the seed the group that became the Nanak Panth. (The word panth literally means "path," here it refers to those Sikhs who followed Guru Nanak's path of liberation). [Source: Pashaura Singh, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Religious Practices”, Thomson Gale 2006]

In Kartarpur, Nanak established one of the most distinctive social institutions associated with Sikhism — the langar or large community kitchen. This was a radical deviation from the traditional Hindu community norms, where caste rules prohibited members of different castes from sharing food from the same table or kitchen.

Guru Nanak's Last Years and the Beginning of Ten Gurus

Shortly before his death in 1539 at the age of 70, Guru Nanak appointed a successor. This not only inaugurated a two-century-long Sikh political-spiritual lineage, with each successor taking the title of Guru, it also marked a break with the previous Sant practice of not appointing spiritual successors.

In his later years, Nanak reportedly met the Mughal emperor Babar, who was impressed by Nanak's spirituality. As he neared the end of his life, Nanak sought to appoint a successor. Although he could have easily chosen one of his own sons, he devised a simple test to determine who was most deserving of leading the community. He dropped his eating bowl into a dirty sewer, and one of his disciples, Lehna, retrieved the bowl and presented it to Nanak. Lenha was anointed as Nanak's successor and renamed Guru Angad. He was entrusted with the future of the Sikh faith. [Source: Vinay Lal, professor of history, UCLA ==]

Guru Angad succeeded Guru Nanak and was followed by eight other gurus or teachers. However, their histories belong to the larger history of Sikhism. After Guru Nanak's death on September 22, 1539, Hindus and Muslims both claimed his remains. This incident showed that his simple teachings had not been fully absorbed by either group. Hindus wanted to burn the body, while Muslims wanted to cremate him. In the words of one couplet: “Guru Nanak, the King of Fakirs/ To the Hindu a Guru, to the Mussulman a Pir.==

Although both Muslims and Hindus recognized him as a saint, they viewed him through the lens of their respective faiths. When the quarreling Hindu and Muslim groups pulled the sheet covering Nanak's body, they discovered a pile of flowers. Over time, Nanak's humble faith blossomed into a religion, complete with its own contradictions and customs. ==

See Separate Article: TEN GURUS OF SIKHISM factsanddetails.com

Teachings of Guru Nanak

Guru Nanak was a mystic, poet and practical man who declared his independence from other thought forms of his day. He proclaimed monotheism, the provisional nature of organized religion, and direct realization of God through religious exercises and meditation. He embraced the concepts a classless society and the equality of women, opposed idolatry and the caste system and said there was no need for priests or ceremonial rituals. He worshiped at both Hindu and Muslim holy places and is even said to have gone on pilgrimage to Mecca. [Sources: Columbia Encyclopedia, 6th ed., Columbia University Press; D. O. Lodrick, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life”, Cengage Learning, 2009]

Although Guru Nanak's teachings were largely in line with some of the Sants of his time, his mission is believed to have emerged from his direct experience of the Divine — initiated with the words “na koi Hindu, na koi Mussalman” . ("there is no Hindu, there is no Muslim"). This “third way” became the Nanak Panth, or the Path of Nanak. [Source: Arvind-Pal S. Mandair, “Encyclopedia of India”, Thomson Gale, 2006]

At the heart of his message was a philosophy of universal love, devotion to God, the singularity of the ultimate reality, the consequent unity of humanity. and the equality of all men and women before God. Nanak promoted religious tolerance. His most famous saying was: “There is no Hindu, there is no Muslim.” He perceived God as sat, as truth and being.

Pashaura Singh wrote: “Guru Nanak prescribed the daily routine, along with agricultural activity for sustenance, for the Kartarpur community. He defined the ideal person as a Gurmukh (one oriented toward the Guru), who practiced the threefold discipline of "the divine Name, charity, and purity" (nam-dan-ishnan). Indeed, these three features — nam (relation with the divine), dan (relation with the society), and ishnan (relation with the self) — provided a balanced approach for the development of the individual and the society. They corresponded to the cognitive, the communal, and the personal aspects of the evolving Sikh identity. For Guru Nanak the true spiritual life required that "one should live on what one has earned through hard work and that one should share with others the fruit of one's exertion" (Adi Granth, p. 1,245). In addition, service (seva), self-respect (pati), truthful living (sach achar), humility, sweetness of the tongue, and taking only one's rightful share (haq halal) were regarded as highly prized ethical virtues in pursuit of liberation. [Source: Pashaura Singh, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Religious Practices”, Thomson Gale, 2006]

At Kartarpur, Guru Nanak gave practical expression to the ideals that had matured during the period of his travels, and he combined a life of disciplined devotion with worldly activities set in the context of normal family life. As part of the Sikh liturgy, Guru Nanak's Japji (Meditation) was recited in the early hours of the morning, and So Dar (That Door) and Arti (Adoration) were sung in the evening.

“Guru Nanak's spiritual message found expression at Kartarpur through key institutions: the sangat (holy fellowship), in which all felt that they belonged to one spiritual fraternity; the dharamsala, the original form of the Sikh place of worship; and the establishment of the langar, the dining convention that required people of all castes to sit in status-free lines (pangat) in order to share a common meal. The institution of langar promoted a spirit of unity and mutual belonging and struck at a major aspect of caste, thereby advancing the process of defining a distinctive Sikh identity. Finally, Guru Nanak created the institution of the Guru, or preceptor, who became the central authority in community life.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: “World Religions“ edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “Encyclopedia of the World’s Religions“ edited by R.C. Zaehner (Barnes & Noble Books, 1959); “Encyclopedia of the World Cultures: Volume 3 South Asia” edited by David Levinson (G.K. Hall & Company, New York, 1994); “The Creators “ by Daniel Boorstin; National Geographic, the New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Times of London, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated December 2023