TIBETAN MONKS

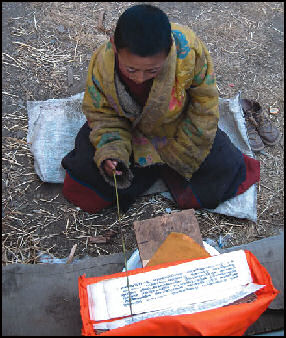

Studying monkReligious life in Tibet revolves around monks and monasteries. The Tibetan word for monk is "trapa," which means “student” or “scholar.” It is used to describe the three main categories of monastery residents: students (monks), and scholars and teachers (lamas). Monks don’t necessarily have to be celibate. Yellow sect monks do not marry, but monks of most other sects are free to do so. The religious leaders of many villages are married lamas.

Tibetan monks play a major role in the lives of the Tibetan people, conducting religious ceremonies and taking care of the monasteries. Sometimes, in order to maintain a household and to avoid the dividing of property, a younger son is sent to the monastery to be a monk — the equivalent of knighting a younger son without property in England — and when the younger brother reaches adulthood, he shares his elder brother's wife. [Source: Washington Post]

According to Reuters there are more than 46,000 monks in Tibet. The number of monks in Tibet in 1950 was about 110,000 — which would be the equivalent per capital of the U.S. having 27 million monks, of which about 35 percent would be of marriageable age. This creates a shortage of available males; and in many sparsely populated areas, it is hard to find a suitable spouse.

Traditionally large numbers of Tibetan males became monks and many families had at least one son who was a monk. In 1959, nearly a quarter of all Tibetan males were monks. The number of monks has been reduced from around 120,000 in 1950 to 14,000 in 1987 and has grown to around 467,000 today, a number fixed by the government since 1994. There are relatively few nuns; they have a reputation for political activism.

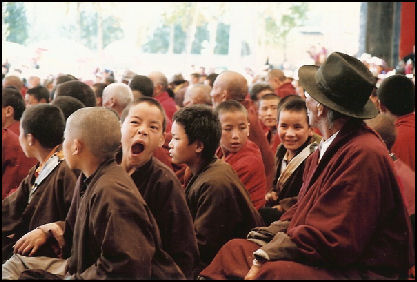

Monks join monasteries when they are a young as five years old. To gain admission they must be approved by a lama and later pass an entrance exam. Monks are expected to develop through meditation, research and training in logic. Children are often recruited when they are very young to be monks. The practice has been criticized. A spokesman for the Dalai Lama told National Geographic, “We find that some of the best scholars began as children though I acknowledge that children don’t really know their own minds at that age.”

Novice monks gain admittance to Sera monastery at age 16 by memorizing 300 scriptures and passing an exam. About 800 monks live at Sera and about 2,000 devotees visit each week.

See Separate Articles: TIBETAN BUDDHISM factsanddetails.com; TIBETAN BUDDHIST LAMAS factsanddetails.com; STORY OF A MILITANT TIBETAN MONK factsanddetails.com; TIBETAN MONASTERIES factsanddetails.com; TIBETAN ARCHITECTURE: TEMPLES, PALACES, STUPAS factsanddetails.com; TIBETAN BUDDHIST PILGRIMS factsanddetails.com; DALAI LAMAS, THEIR HISTORY AND CHOOSING NEW ONES factsanddetails.com;

Websites and Resources Monks and Lamas: Monk Life travelchinaguide.com ; Research on Tibetan Monks case.edu/affil/tibet ; New York Times article on monks studying science nytimes.com ; Monasteries and Pilgrims: Monastery Preservation asianart.com ; Wikipedia list Wikipedia ; Book: “Path to Buddha: A Tibetan Pilgrimage” by Steve McCurry (Phaidon Press, 2003) Mt. Kailash Wikipedia Wikipedia Sacred Sites Sacred Sites Summit Post Summit Post

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:“The Sound of Two Hands Clapping: The Education of a Tibetan Buddhist Monk” by Georges B. J. Dreyfus Amazon.com; “From a Mountain In Tibet: A Monk’s Journey” by Yeshe Losal Rinpoche Amazon.com; “The Life of a Tibetan Monk” by Geshe Rabten Amazon.com; :The Autobiography of a Tibetan Monk” by Palden Gyatso Amazon.com; “Himalayan Hermitess: The Life of a Tibetan Buddhist Nun” by Kurtis R. Schaeffer Amazon.com; “Labrang Monastery: A Tibetan Buddhist Community on the Inner Asian Borderlands, 1709-1958" by Paul Kocot Nietupski Amazon.com; “Sera Monastery” by José Cabezón and Penpa Dorjee Amazon.com; Tibetan Buddhism: “Essential Tibetan Buddhism” by Robert A. F. Thurman Amazon.com; “Initiations and Initiates in Tibet” by Alexandra David-Neel Amazon.com; “The Secret Oral Teachings in Tibetan Buddhist Sects” by Alexandra David-Neel, Lama Yongden Amazon.com; Introduction to Tibetan Buddhism by John Powers Amazon.com; “The World of Tibetan Buddhism: An Overview of Its Philosophy and Practice” by His Holiness the Dalai Lama, Geshe Thupten Jinpa Amazon.com; “Tibetan Buddhism: With its Mystic Cults, Symbolism and Mythology, and in Its Relation to Indian Buddhism” by L Austine Waddell Amazon.com; “The Jewel Tree of Tibet: The Enlightenment of Tibetan Buddhism” by Robert Thurman and Sounds True Amazon.com; “A Concise Introduction to Tibetan Buddhism” by John Powers Amazon.com; “The Preliminary Practices of Tibetan Buddhism” by Geshe Rapten Amazon.com; “Teachings and Practice of Tibetan Tantra” Amazon.com; “Tantra in Practice” by David Gordon White Amazon.com

Deciding to Become a Tibetan Monk

William Dalrymple of the Paris Review talked with an elderly monk named Tashi Passang. The monk said, “I was born in 1936 in the Dagpo district of the Kham region. Like many in eastern Tibet, my family lived a seminomadic life. We were small landowners with a stone three-story house, and we had many yaks. In the summer the boys of the family had to help my grandparents and my uncles to take the herds up to the high summer pastures. [Source: William Dalrymple, Paris Review, Spring 2010]

“For my third summer in the mountains, my great-uncle came with us. He was a monk, though he no longer lived in a monastery. My mother had taught me to read and write a little Tibetan, and my uncle thought that I was a promising boy who might benefit from a monastic education. Every day he would sit with me and teach me to write on a slate, or on the bark of a tree, as there was no paper in the mountains. He also loved history, and was a good storyteller. As we tended the animals, he would tell me long stories about Songtsan Gampo and the kings and heroes of Tibet.”

“But his main love was the dharma, and he told me that if I continued to lead the life of a layman I might acquire many yaks, but would have nothing to take with me when I died. He also said that married life was a very complicated business, full of responsibilities, difficulties, and distractions, and that the life of a monk was much easier. He said that it gave you more time and opportunities to practice your religion.”

“By the end of the summer I had decided that I would like to try monastic life. I thought that if I really dedicated myself to religion I would have a better chance of a good rebirth in my next life and have the opportunity to gain nirvana. My uncle and I guessed that my parents would forbid me from becoming a monk, so we decided that I should join the monastery first, and only later inform the family. At the end of the summer, when we came down from the passes, my uncle and I went to Dagpo monastery, and he handed me over to the abbot.”

Tibetan Buddhist Monk Life

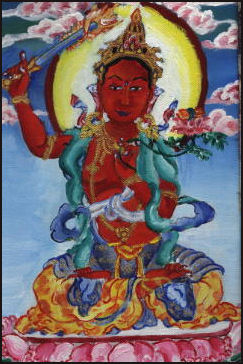

Bodhisattva Manjushri Monks live as simply as possible They follow the model of the Buddha who traded in his clothing for simple robes. Monks shave their heads and faces to discourage vanity. Monks have traditionally lived a cloistered existence. One Tibetan monk said, "When I was a child we Tibetans were like frogs in a well. We saw the walls of the well and the sky above. That was our world."

Passang said, “As it turned out, I was happier in the monastery than I had ever been. In my life as a herdsman, I had to worry about protecting my yaks from wolves, and I had to look after my grandparents. Life was full of anxieties. But as a monk you just have to practice your prayers and meditation, and to hope and work for enlightenment. Also, life in the mountains, for all its beauty, was quite lonely. In Dagpo there were nearly five hundred monks, and many boys of my own age. I made a lot of friends. I knew I had made the right decision. Before long even my parents became reconciled to what I had done.” [Source: William Dalrymple, Paris Review, Spring 2010]

“How you start your life as a monk can determine the rest of your life. One of our teachings is, Men who have not gained spiritual treasures in their youth perish like old herons in a lake without fish.The main struggle, especially when you are young, is to avoid four things: desire, greed, pride, and attachment. Of course no human being can do this completely. But there are techniques that the lamas taught us for diverting the mind. They stop you from thinking of yaks, or money, or beautiful women, and teach you to concentrate instead on gods and goddesses.” [Ibid]

Tibetan Buddhist Monk Daily Life

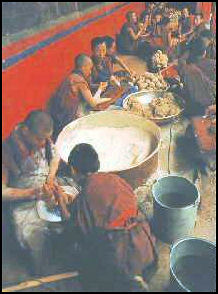

Tibetan monks rise at 5:30am offer holy water and light yak butter lamps to honor Buddha and the Dalai Lama, and pray and meditate for five hours. Near midday, two monks climb a central temple and blow a horn, calling the senior monks to prayer. In the afternoon monks generally attend classes, participate in discussions on religious doctrine, say prayers for the dead “to help their soul reach heaven” and engage in debates with other monks. Prayers and study are stopped up to nine times a day for teas and simple meals. Many monks carry a bowl for eating tucked into a fold in their robes.

Monks sit cross-legged in rows when they chant prayers. Describing a group of chanting monks in Mongolia, Thomas Allen wrote in National Geographic, "Dozens of monks sat in the center of the temple, while the world of tourists and worshipers whirled around them. In a counterpoint of human and sacred sounds, babies cries sharply rose and fell against the undulating, ceaseless chanting. A gong throbbed unseen in a mist of incense...The monks sat in facing rows, eyes fixed on some inner eternity, hands gracefully moving as they hold their dark beads and tinkled tiny bells. Many of the monks in the back rows were young."

Tea is considered essential by all Tibetans, lamas included. Every morning, lamas attend a morning prayer sessions led held under the aegis of the sutra teacher. This is followed the consumption of buttered tea and tsampa. At noon, they gather in the sutra hall of the Buddhist school of the monastery to pray and recite Buddhist scriptures while drinking tea. This ceremony is much the same as the morning mass, but is held on a smaller scale. In the evening, lamas gather in the Khang-tshan to pray and drink tea in a fairly informal setting. In Tibetan this is called Kamqa. It is very common for benefactors to visit monasteries, where they offer tea porridge to lamas while presenting them with the names of the Buddhist scriptures they wish the lamas to recite for them. There are also senior lamas studying for Geshi, a Buddhist academic degree equivalent to a Ph.D, who also offer tea porridge to the lamas of the whole monastery. [Source: Chloe Xin, Tibetravel.org]

Monks use wooden bowls. People who know the monasteries well can tell which monastery the monk is from based on the shape of the bowl. The iron-club lamas always move the bowl from one hand to the other playfully, which is quite dazzling. In religious meetings, when the iron-club lama keeps order, his wooden bowl is an emblem of authority that is used to knock the head of those who do not observe the order. Clergy and laypeople making obeisance to the Dalai Lama in the morning were usually awarded three bowls of butter tea. While they listened respectfully to the Dalai Lama or the prince regent, they sipped the butter tea from their bowls constantly. [Source: Chloe Xin, Tibetravel.org]

Tibetan Monk Training

On his training Passang said, “It was very rigorous. For three years we were given text after text of the scriptures to memorize. It was a slow process. First we had to master the Tibetan alphabets. Then we had to learn a few mantras, then slowly we were taught the shorter versions of the scriptures, or tantras. Finally we graduated to the long versions. At the end of this period we were each sent off to live in a cave for four months to practice praying in solitude. There were seven other boys nearby, in the same cliff face, but we were not allowed to speak to one another. [Source: William Dalrymple, Paris Review, Spring 2010]

“Initially I felt like a failure. I was lonely, and scared, and had a terrible pain in my knees from the number of prostrations we were expected to do thousands in a day but by the end of the first fortnight, I finally began to reflect deeply on things. I began to see the vanity of pleasures and ambitions. Until then I had not really sat and reflected. I had just done what I had been taught and followed the set rhythms of the monastery.” [Ibid]

“I felt that I had found myself in the cave. My mind became clear, and I felt my sins were being washed away with the austerity of the hermit life, that I was being purified. I was happy. It is not easy to reach the stage when you really remove the world from your heart. Ever since then I have always had a desire to go back and to spend more time as a hermit. But it was not meant to be. As soon as I returned from those four months of solitude, the Chinese came.” [Ibid]

Tibetan Buddhist Monk Rules

monk chores

In the Yellow Hat sect a monk initiate makes initial vows, known as the "genyen" or "getsui" ordination, in which he vows to give up secular life and become celibate. This is the beginning of a long road of study and meditation. If he stays the course he becomes ordained as a monk with full "gelung" vows.

Monks are not supposed to marry, quarrel, smoke, drink or eat meat. They wear maroon robes and carry prayer beads. Sometimes Tibetan monks carry staffs that signify their rank. Many monks are trained for specific duties such as administration, teaching or cooking. In the old days many monastery had “fighting monks” that were trained in the martial arts and expected to defend the monastery if attacked or even attack rival monasteries if there was some dispute.

Monks have not always been celibate.. In the old days it was customary for senior monks to keep young boys and girls as “drombos” (passive sexual partners) and marry noble women who bore them children.

William Dalrymple of the Paris Review talked with an elderly Tibetan monk named Tashi Passang. The monk said, “The main struggle, especially when you are young, is to avoid four things: desire, greed, pride, and attachment. Of course no human being can do this completely. But there are techniques that the lamas taught us for diverting the mind. They stop you from thinking of yaks, or money, or beautiful women, and teach you to concentrate instead on gods and goddesses.” [Source: William Dalrymple, Paris Review, Spring 2010]

When asked about the techniques to rid oneself of desire and attachment, a Tibetan monk said, “The lamas taught us to stare at a statue of the Lord Buddha and absorb the details of the object the color, the posture, and so on, reflecting back all we knew of their teachings. Slowly you go deeper; you visualize the hand, the leg, and thevajra in his hand, closing your eyes and trying to travel inward. The more you concentrate on a deity, the more you are diverted from worldly thoughts. It is difficult, of course, but it is also essential. In the Fire Sermon, the Lord Buddha said, The world is on fire and every solution short of nirvana is like trying to whitewash a burning house. Everything we have now is like a dream impermanent. This floor feels like stone, this cupboard feels like wood but really it is an illusion. When you die you can’t take any of this. You have to leave it all behind. We have to leave even this human body.” [Ibid]

Tibetan Buddhist Monk Tasks

More Monk chores

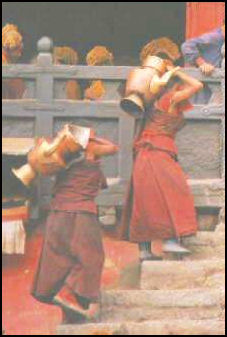

The life of a monk is not all just quiet meditation and study. New arrivals and junior monks especially perform chores like doing the laundry, sweeping floors and fetching water. Young monks are often running around with pots of tea in their hands, delivering them to senior monks. To earn merit on Buddha’s birthday some monks walk around and around their monasteries the entire day, carrying heavy wooden-bound prayer books. Many classrooms in monastery colleges are outfit with buckets. If a monk can't remember a text he was supposed to recite he has to wear a bucket of water around his neck until he gets it right.

According to the “Encyclopedia of World Cultures": Monks conducted most public religious ceremonies (including operatic performances), which constituted the bulk of Tibetan ceremonial life and followed the traditional Buddhist calendrical cycle. Oracles, mediums, and exorcists were also commonly monks but could be local peasants in rural areas. In western Tibet and pastoral areas of Qinghai, an earlier form of Buddhism mixed with the pre-Buddhist native religion (Bon) is practiced. [Source: Rebecca R. French, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 6: Russia — Eurasia / China” edited by Paul Friedrich and Norma Diamond, 1994]

Monks have traditionally subsisted off of food from their labors, donations from farmers and herders and contributions from their families. Buddhists believe that each monk’s spiritual quest helps the entire community. Sending sons to become monks earn merits for their parents.

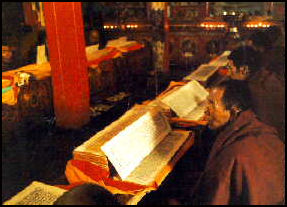

Monk initiates have traditionally been divided into groups according to social status and ability and given training for a variety of tasks. Many monks spend their time laboriously duplicating sacred books by hand with intricate hand-carved printing blocks. The Buddhist scriptures are printed in three-foot-long books that are produced in sets consisting of 100 or more volumes. Buddhist monks at the Baoguang monastery in southwest Sichuan formed China's first and only monk fire department in 1989. About 80 of the monastery's 130 monks are members of the department and newly-recruited monks are trained in fire fighting.

Catholic monks have come to Tibetan monasteries to learn meditation techniques and Tibet monks have been sent to Catholic missions to lean how to set up orphanages, homes for the elderly, schools and hospitals. In Tibet, villages and families traditionally took care of these things. With the Dalai Lama in exile in India the traditional structure has collapsed and the monasteries have had to take over.

Studying and Debating Monks

The degree of religious teacher, dge bshe, requires more than ten years of diligent study, memorization of texts, practice in debate, and examinations. Many monks spend their time debating subtle points of Buddhist theology such as "whether or not a rabbit has a horn" or "whether form has shape and color." The abbots and teachers usually stand while the monks sit on the floor. In their free time monks play soccer, wrestle and goof around. In some monasteries monks participate in debates in the main assembly hall of the monastery, observed by local spectators and tourists. This is sometimes followed by ritual music played outside. Examinations for the highest 'Lharampa Geshe' degree (a degree in Buddhist philosophy in the Geluk tradition) are held during the week-long Great Prayer Festival in Lhasa in January.

Describing debating monks in a monastery, Tim Sullivan of Associated Press wrote: “The shouts of more than a dozen Tibetan monks echo through the small classroom. Fingers are pointed. Voices collide. When an important point is made, the men smack their hands together and stomp the floor, their robes billowing around them. It's the way Tibetan Buddhist scholars have traded ideas for centuries. Among them, the debate-as-shouting match is a discipline and a joy. [Source: Tim Sullivan, Associated Press, July 3, 2012 ^/^]

“Though most studied only religious subjects after eighth grade and few learned anything but basic math, they regularly traverse highly complex concepts. Because of the way they study — focusing on debates and the memorization of long written passages, but doing comparatively little writing — few are able to take notes during classroom lectures. Many were raised to see magic as an integral part of the world around them. ^/^

“To watch them in class, though, is astonishing. No one yawns. No one dozes. Since almost no one takes notes, it's easy to think they're not paying attention. For most of the monastics, the challenges are not in the academic rigor. They see nothing astonishing about their ability to process vast amounts of information without taking notes, or to remain attentive for hours on end.

See Monastery Education Under EDUCATION IN TIBET Separate Article factsanddetails.com

Tibetan Monk Clothes

Monks shave their heads and face to discourage vanity and to live as simply as possible. They wear simple robes following The Buddha who traded his clothing for simple robes in the 6th century B.C.. Clothing articles for Tibetan monks include a waistcoat and a red monk skirt. They wrap dark red kasaya (robes), twice the body's length, obliquely about their shoulders. When monks pray, they wear a red cloak made of wool, which is called dagang in Tibetan. After the monks are promoted to Gexi (the highest academic degree of Tibetan Buddhism), their waistcoats are rimmed with satin borders, and they hang satin water bags about their waists, in which is a small bottle for mouth-rinsing. Monks who are responsible for blowing suona horn and monastic bugle may also wear these things as ornaments. [Source: Chloe Xin, Tibetravel.org]

Monks shave their heads and face to discourage vanity and to live as simply as possible. They wear simple robes following The Buddha who traded his clothing for simple robes in the 6th century B.C.. Clothing articles for Tibetan monks include a waistcoat and a red monk skirt. They wrap dark red kasaya (robes), twice the body's length, obliquely about their shoulders. When monks pray, they wear a red cloak made of wool, which is called dagang in Tibetan. After the monks are promoted to Gexi (the highest academic degree of Tibetan Buddhism), their waistcoats are rimmed with satin borders, and they hang satin water bags about their waists, in which is a small bottle for mouth-rinsing. Monks who are responsible for blowing suona horn and monastic bugle may also wear these things as ornaments. [Source: Chloe Xin, Tibetravel.org]

The costumes of Tibetan monks are usually made of crimson pulu. In daily life, a monk wears a shawl with the front and the back decorated with yellow cloth, and a long skirt, and drapes another long shawl that is approximately 2.5 times of the length of his height. When he attends a religious meeting he will wear a cloak and a special yellow cap. Sticking up high on the head, this neatly sewed cap resembles the shape of a rooster's comb. Virtually the costumes of monks varies among different sects. For example, some other monks wear long, steeple-crowned hat with its brim folded and its front open.

Hats are also important costume for Tibetan monks and distinctive feature of different schools of Tibetan Buddhism, for example, Red Hats for Nyingmapa and Yellow Hats for Gelugpa. Monks of different sects can be easily distinguished by their coronary caps. For example, senior monks of the Ningma Sect wear lotus caps shaped like thrones. It was said that such caps were once worn by Padmasambhava, a senior Indian monk who had come to preach his religion in Tibet. Monks of the Sakya Sect wear heart-shaped caps called the "sakya cap." The golden-rimmed red caps, which were also said to be granted by an emperor of the Yuan Dynasty, but were later changed to yellow caps by Tsong-kha-pa.

Although monks' attire is determined by rigid rules, nuns' attire is determined mostly by their financial situation. Their waistcoats may be rimmed with satin, but their skirts and kasaya are usually made of tweed. Sometimes they patch a piece of satin on their shoes to represent their different status. Along with the fast development of society, monk's and nun's clothes have been undergoing changes. Now it is not unusual to see Buddhist monks and nuns wear sport shoes and watches.

Debating monks

Tibetan Monk Robes

Robes are the most common costume of Tibetan monks. The basic robe consists of the following parts: 1) The dhonka, a wrap shirt with cap sleeves, usually is maroon or maroon and yellow with blue piping. 2) The shemdap is a maroon skirt made with patched cloth and a varying number of pleats; 3) The chögu, something like a sanghati, a wrap made in patches and worn on the upper body, although sometimes it is draped over one shoulder like a kashaya robe. The chögu is yellow and worn for certain ceremonies and teachings; 4) the zhen, similar to the chögu, but maroon, and is for ordinary day-to-day wear; 5) the namjar is larger than the chögu, with more patches, and it is yellow and often made of silk. It is for formal ceremonial occasions.

Tibetan robes are called "Kasaya", a translation of Sanskrit whose original meaning was "color that is not pure" or "bad color". Because the robe worn by monks was traditionally made of "color that is not pure" (variegated color), it was called kasaya. Later the color of monk's clothes changed. Today, different types are worn for different occasios. For example, when monks hold ceremonies, they often wear Jinlan clothes (kasaya woven with gold thread). [Source: Liu Jun, Museum of Nationalities, Central University for Nationalities, kepu.net.cn ~]

Kasaya is basically a wrapping sheet about 70 centimeters wide, and is 2.5 times as long as human body. When monks wear them, they are wrapped on the upper body, leaving the right shoulder exposed, and reaching the instep. Kasayas are different according to different levels of ranks and positions in terms of quality and the color of the cloth. Robes edged with yellow brocade or have yellow silks and satins in normal times are mostly worn by high-level monks or lamas. The styles of kasaya and ways of wearing them are almost the same for the four main Tibetan sects: Ningma, Sajia, Gaju, and Gelu. Its is mainly the hats that are different. Ceremonial kasayas are made of cut cloth sewed into netted checks. They are pieced together with square satin in a fish scale style, meaning that pieces are sewn on the cloth started from the middle, one upon another, to the edges. The threads are sewn horizontally across the edge in an interlocking fashion. ~

The way of the monks to wear the robe usually depends on their sect and areas. The most universal one is that which is worn for the alms-round when the robe is covering both the shoulders. The two top corners are held together and the edges rolled tightly together. The roll is then pushed over the left shoulder, down the back, under the armpit and is pressed down with the left arm. The roll is parted in front through which protrudes the right arm. Within the monastery or residence and when having an audience with a more senior monk, a simpler style is adoped (as a gesture of respect and to facilliate work). The right side of the robe is pushed under the armpit and over the robe on the left leaving the right shoulder bare.

See Endangered Animals.

Trouble Getting New Tibetan Monks

A couple decades ago there were very few monks left as a result of Chinese repression and most of the monks were elderly. After China opened up after the Cultural Revolution many young men in Tibet became monks. Asked why he became a monk, one 22-year-old monk told the Washington Post, "I joined of my own free will. Every time I met a monk, I had a good feeling."

Monasteries have a hard time getting new recruits. In Nepal, few Sherpas become monks these days, and of those who try two thirds eventually quit. One monk told National Geographic, “No one wants to become a monk when they?ve already danced with girls.” "Some fall in love with girls," one trainee said, "Others can't take the responsibility." One man who was a monk for 16 years left for "chang and a good woman."

In Tibet, many monks are lured by money and run off and work as laborers or in restaurants. The number of senior priests is also declining.

Changing Tibetan Monks

The monks themselves are changing. These days monks sometimes wear blue running shoes under their maroon robes and suck on popsicles and smoke cigarettes after the meditation sessions are over. Many wear soft wool robes rather than ones made of coarse cloth and study Mandarin and English to keep up with the times.

There are monks that are always on their cell phones and love tinkering with electronics. Some talk on cell phones while they do the circuit at Jokhang.

Monks with flashy sunglasses, riding motorscooters, are becoming a common sight. Some are involved in the smuggling of precious antiques and selling statues and to German and Japanese tourists. Small bronze statues taken from monasteries have been sold by monks for between $5,000 and $50,000.

Chinese Rules and Tibetan Monks

The Chinese government bans monastic education before the age of 18. The government justifies this policy by arguing that monasteries only teach religion and the Tibetan language and students need a complete education with sciences, the Chinese language and math. Many parents ignore the law and quietly send their sons off to monasteries for religious training. Senior monks have said that after attending regular schools for nine years many young Tibetans don’t want to become monks.

In many monasteries monks are not allowed to watch DVDs, surf the Internet or use cell phones in accordance with Beijing rules. They are told that pictures of the Dalai Lama are banned and reminded not to listen to what people outside China say.

Monasteries have been ordered to stop holding public teachings and are required to allow the Chinese government to conduct classes. One monk in Shigatse told the Washington Post, “We have enough to eat and enough clothes, but our spirits are heavy. There are political education classes every Tuesday and Friday now, and everyone is scared. We can’t even trust our senior monks.”

Foreign tourists have described undercover monks at some of the monasteries they have visited. One American couple told Lonely Planet that they gave one monk at Tashilhunpo monastery in Shigatse some tapes of speeches by the Dalai Lama. Later the couple was picked up by police, with the “monk” on hand to identify them. They were interrogated at police station and had their hotel room searched. Possessions connected to the Dalai Lama were confiscated.

Re-education Classes for Tibetan Monks

A monk at the Dege printing factory told National Geographic, “Fifteen times a year, Chinese officials visit the monasteries and conduct “patriotic education” Each class lasts two or three hours. Basically they tell the monks the Dalai Lama is evil and that he wants to split the motherland. The monks must pretend to listen, but most manage to block it out by chanting silently to themselves.”

In recent years regular re-education classes have been stepped up and have become part of monastic life in Tibet. Attendance is mandatory — unless a monk is sick and then a letter from a doctor is necessary be excused from the class.

The re-education classes used to take place once or twice a month then they were increased to once or twice a week. Now at some monasteries they occur almost daily. One monk told the Times of London that in the morning, “We gather in the main hall and Communist Party officials deliver a speech telling us to be patriotic and they give each monk a paper to read.” In the afternoon the monks return to answer questions related to the paper. “Usually, it’s pretty relaxed. If I can’t remember my answers, then I just repeat the same as the monks in front of me.”

“Sometimes it turns more serious. That is when the police arrive. They may stand beside each monk listening carefully to make sure each answer is correct. If the police come we have to lie. We have to say, “I love the motherland. I don’t love him.” They don’t require you to explain who “him” is, because we all know.”

Image Sources: Julie Chao, , Shunya.net, Purdue University

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated September 2022