THE IDEA OF FACE IN CHINA

losing face The Chinese are very conscious of face. Face is essentially respect in a community and is a crucial underpinning of society. Loss of that respect threatens the relations of individuals with almost everyone in his or her world and is hard to get back once lost, and thus must be avoided at all costs.Face is called "mianzi" in mandarin, which can also be translated to mean “dignity, prestige and reputation.” It has been said that "face is more important than truth or justice." Losing face if often people's worst fear. Chinese go out of their way to be polite and accommodating, to maintain dignity in a variety of situations and avoid disputes, conflicts and embarrassment in their pursuit to avoid losing face.

Chinese value loyalty and stress the importance of keeping one's word and discretion. This is tied with humility and not causing others to lose face. The government often uses social pressure in the form of face-losing criticism to keep people in line on issues such as having extra children or complaining about the government (the threat of imprisonment is also used). Maintaining face and avoiding losing face are important concepts in the West. But as Scott Seligman, author of “Chinese Business Etiquette, Manners and Culture in the People’s Republic of China” told the New York Times, “The Chinese raise face to a high art. It’s a fragile commodity in China that can easily be lost....The trigger doesn’t have to be extreme. You can contradict somebody in front of someone who is lower ranking and cause that person to lose face. Even the simple act of saying no to somebody can make that person lose face.”

Arthur Henderson Smith wrote in “Chinese Characteristics” in 1894: Face “is literally a "compound noun of multitude," with more meanings than we shall be able to describe, or perhaps, even to comprehend. Sometimes it signifies the exhibition to spectators — for the Chinese is always supposed to. be in the presence of on-lookers — of certain conditions which lead others to do him honour. Jn this point of view it is nearly synonymous with "fame, or. reputation" (ming), but the idea of the scenic effect is never absent. A departing mandarin, who has a tablet presented to him, receives "face" by, such a gift. [Source:“Chinese Characteristics” by Arthur Henderson Smith, 1894. Smith (1845 -1932) was an American missionary who spent 54 years in China. In the 1920s, “Chinese Characteristics” was still the most widely read book on China among foreign residents there. He spent much of his time in Pangzhuang, a village in Shandong.]

Websites and Sources: Book: Understanding the Chinese Personality mellenpress.com ; Understanding Chinese Business Culture legacee.com ; Status of Chinese People Blog chinaview.wordpress.com ; Chinese Human Genome Diversity Project www.pnas.org ; Opinions on Asian Fetish colorq.org ; Essay on Humor, China and Japan aboutjapan.japansociety.org ; . Book: One of the most enlightening books about China is “Chinese Lives” by Sang Ye and Zhang Xinxin, a series of interviews with ordinary Chinese talking very candidly about what matter to them.

See Separate Articles ASIAN CHARACTER AND PERSONALITY: HAPPINESS, LOSING FACE, CONFUCIANISM AND BUDDHISM factsanddetails.com ; PEOPLE OF CHINA: DIVERSITY, ASSIMILATION, HAN AND ETHNIC RELATIONS factsanddetails.com ; HAN CHINESE factsanddetails.com ; CHINESE PHYSICAL CHARACTERISTICS AND STRENGTH factsanddetails.com ; CHINESE PERSONALITY AND CHARACTER: CONFUCIANISM, COMMUNISM AND DIVERSITY factsanddetails.com ; SOCIALIZING AND SOCIAL CUSTOMS IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; HAPPINESS AND PSYCHOLOGICAL PROBLEMS IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; HUMOR IN CHINA: ITS HISTORY AND FORMS OF EXPRESSION factsanddetails.com ; STRESS, ARGUING AND BULLIES IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; CALLOUSNESS IN CHINA, GOOD SAMARITANS AND THE HIT-AND-RUN DEATH OF A TWO-YEAR-OLD factsanddetails.com ; CHINESE CHARACTERISTICS”: A SEMI-RACIST BUT INSIGHTFUL VIEW OF CHINA FROM 1894 factsanddetails.com ; REGIONAL DIFFERENCES IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; BEIJING VERSUS SHANGHAI factsanddetails.com ; CHINESE SOCIETY, CONFUCIANISM, CROWDS AND VILLAGES Factsanddetails.com/China ; CHINESE SOCIETY AND COMMUNISM Factsanddetails.com/China ; RELIGION, FOLK BELIEFS AND DEATH ( Main Page, Click Religion) Factsanddetails.com/China JAPANESE PERSONALITY AND CHARACTER Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; JAPANESE SOCIETY Factsanddetails.com/Japan

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: “It's All Chinese To Me: An Overview of Culture & Etiquette in China” by Pierre Ostrowski Matthew B. Christensen, Gwen Penner (Illustrator) Amazon.com; “China in Ten Words” by Yu Hua, translated from the Chinese by Allan H. Barr (Pantheon) Amazon.com; “Culture Hacks: Deciphering Differences in American, Chinese, and Japanese Thinking” by Richard Conrad Amazon.com; Amazon.com; “Chinese Characters: Profiles of Fast-Changing Lives in a Fast-Changing Land” by Angilee Shah, Jeffrey Wasserstrom, et al. (2012) Amazon.com; “The Chinese Mind: Understanding Traditional Chinese Beliefs and Their Influence on Contemporary Culture” (2009) by Boye Lafayette De Mente Amazon.com; “China Men”, a National Book Award Winner by Maxine Hong Kingston Amazon.com; “Understanding the Chinese Personality: Parenting, Schooling, Values, Morality, Relations, and Personality” (1998) by William J. F. Lew Amazon.com; “Niubi!: The Real Chinese You Were Never Taught in School” by Eveline Chao and Chris Murphy Amazon.com; “The Ultimate Chinese Dictionary of Swear Words: a Chinese Phrase Book of Essential Colloquial Chinese Slang With Contextual Information and Sample Sentences by Liu San Amazon.com; “The Guide to Chinese Horoscopes: The Twelve Animal Signs” by Gerry Maguire Amazon.com; “Chinese Characteristics” (1894) by Arthur H Smith Amazon.com; “Readings in Han Chinese Thought” by Mark Csikszentmihaly Amazon.com; “The Good Earth” by Pearl Buck(1931). Amazon.com;“The Book of Chinese Names: A Guide to Auspicious and Elegant Names” by Goh Kheng Chuan and Goh Kheng Yew Amazon.com

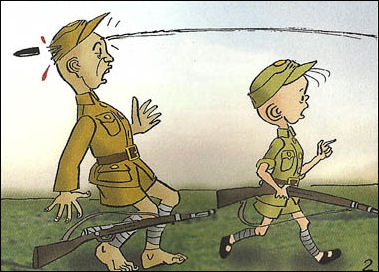

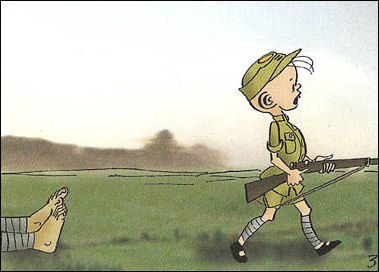

Losing Face in China

Henderson Smith wrote in “Chinese Characteristics”: Anything which is spontaneously proffered, and which could not be exacted, gives the recipient an amount of "face" proportioned to the importance of the gift, and of those presenting it. But since reciprocity is inherent in presentation, it is of the first consequence that everything so givep should be not simply acknowledged, but acknowledged suitably. Few foreigners would presume to decide as to what constitutes a suitable acknowledgment of a Chinese gift. But not to acknowledge it in a suitable way, would be not simply to nullify the effect of the gift, but it would cause the recipient to "lose face." Into the complicated labyrinth of what may be a suitable acknowledgment of a Chinese present, most foreigners who have much to do with the Chinese, are sooner or later sure to be enticed. A gift cannot be entirely declined. It cannot always be declined in part — especially if it be a new-year caller with a bunch of artificial flowers, and a salutation; so the coolie who brings it to the door of the consul, is paid a Mexican dollar for his trouble. The coolie is happy, but the consul is exasperated. Yet he does not wish to lose face, and so he submits to the extortion. To decline a gift especially prepared, such as a tablet, or even a simple pair of scrolls, might give great offence, unless it is done while the matter is still in embryo — and this for obvious reasons is generally impossible. [Source:“Chinese Characteristics” by Arthur Henderson Smith, 1894]

In a case within our knowledge, a few Chinese resolved to present a foreigner with a token of this sort, which the foreigner resolved not to accept. When a single step has been taken in the affair, it is too late according to Chinese ideas to decline, for the will of the many must be respected. So the inscription was bought, and arrangements were made to present it, when, to the dismay of the donors, the obstinate foreigner, who had not enjoyed the advantage of an education Of which a book of propriety is a part, absolutely refused to receive it. Here was a case of the irresistible projectile, impinging against an invulnerable target. The present could not go back, and the crass foreigner would not receive it. In this crisis the middle-man, through whom the business had thus far proceeded, consented to take charge of it, with the concurrence of both parties, the would-be givers, and the would-not-be receiver. After a certain lapse of time, the obnoxious present was surreptitiously sent to the premises of the (theoretically unwilling) recipient, and thrust into an unused drawer. Thus the donors had sent it — somewhere, while the recipient (theoretically) never received it, and what is of chief importance, the "face" of both parties was saved!

“In a great range of cases constantly occurring in Chinese social relations, “face" is not synonymous with honour, much less with reputation, but it is a technical expression so indicate a certain relation instinctively perceived by a Chinese, but almost incomprehensible to the poor foreigner. The knight in Chinese chess has the same diagonal movement as in the western game — one square forward, and two side-wise — or vice versa. But if there happen to be a piece on the square lying at the inner angle of the knight's move, he cannot stir. This, we are informed, is because the other piece “tangles" the horse's legs.

Saving Face in China

Smith wrote: Like the invisible check, is the mysterious something which enables a person to recover "face." Suppose, for example, the question is about the property of a widow, against whose disposition of it, some one has entered a lawsuit, though it clearly lies in the widow's full power, there being no heirs, the magistrate inclines to the side of the objectors, and having ascertained that no certain proof of the death of the widow's husband (though deceased for fifteen years) is available, he confirms the disposition of the property, with this significant proviso, that if the husband turns up again, the property shall be his! This saves the face of the prosecutor, and leaves him with a drawn game. [Source:“Chinese Characteristics” by Arthur Henderson Smith, 1894]

“The most cursory perusal of the reports of commissions appointed to examine into the conduct of officials, as presented in the Peking Gazette, illustrates the force of fees in the saving of face. "We find, they say in effect, to take a recent instance, that the officer was innocent; he did quite right, arid all the suspicious circumstances may be explained in natural and easy ways. (For which verdict Tls. 5,000 may have been received). But,as A.B. did not maintain so high a quality of virtue as to prevent himself being talked about we recommend depriving him of his button, and retention at his post. In this way a careful balance of “face" is maintained all around.

“For a servant to be summarily dismissed, is perhaps regarded as a disgrace, certainly a loss of ". face." If he has wind of the intention, he will very likely save his “face," by refusing to perform some simple task, raise a storm over a trifle, retire in triumph, with his “face" intact. One dead to shame has a “thick face" or has the skin of his forehead dissected off (as in the punishment of ling-ch'ih,) so as to hide 'his face. To;save one's "face" arid 'lose one's head, would not seem so attractive to an Occidental as to a Chinese. Yet we have heard of a district magistrate who was allowed as a special favor, to be beheaded in his robes of office, in order to save his face.

Dread of Giving Offence in 19th Century China

Smith wrote in “Chinese Characteristics”: ““The practical relations, which the Chinese dread of giving offence to their countrymen bear to foreigners, are many and important. It controls our employes, to a degree which is often little suspected. We have decided to dismiss an objectionable servant, and mentally resolve to promote one more worthy to his place, when to our chagrin, both servants disappear at once and forever, one of them for no assignable cause. By this we mean no cause that we can assign, through every other servant knows that the second servant left, not because he wished to xlo so, but because the first one would not allow him to remain. Everyone has found that a Chinese scholar in foreign service cannot be replaced by another, as long as he has not been actually discharged. There is sound basis for the common saying, “If the old does not go, the new will not come," that is he will not dare to do so. [Source:“Chinese Characteristics” by Arthur Henderson Smith, 1894]

“The principle which we are considering helps to explain what must have appeared to many persons at some stage of their experiences in China, very singular, that whenever a case of any complexity arises, it is next to impossible to get at the "bottom facts.'' The reason is perfectly simple. There are often no facts, and not infrequently there is, as the pilots say, "no bottom." The fact that some person with whom we happen to be concerned is a gambler, or an opium smoker, becomes highly probable, but we cannot prove it. It is one of those secrets the magnitude of which is gauged by the number of people who are in it; but the facts, well-known as they are, will be successfully kept from the foreigner for a long time, illustrating the difficulty, already mentioned, of getting at a notorious truth. There may be a great deal of electricity in the air, and abundant evidences of its presence, while it is yet hard to materialize it into a spark, which shall give light.

“The secretive habits of the Chinese in regard to matters which may be the occasion to themselves of trouble, render the execution of Chinese justice, in its best estate, a matter very different from that to which we are accustomed. Of evidence in our sense of the term, it would seem as if the Chinese have no knowledge, and for it they do not appear to care. Many of the Chinese judicial processes resemble the practice which is said to prevail with French lovers, who, when they grow tired of one another write a note, simply saying, "Farewell, I know all." There is usually enough to be known, so this ends the matter. It is generally safe to assume that if a particular charge cannot be adequately sustained, others just as bad may be true, and the truth is found not by a minute examination, but by a balancing of probabilities, combined with a large percentage of shrewd guessing. A dying man was recommended by the priest to “renounce the deyil, and all his works," to which he made the suggestive reply, "I'm going to a strange country, and I don't want to make meself any inimies!" The Chinese is in a country which he understands too well to make himself needless "inimies" — especially if it is merely to please a foreigner.

Shyness, Modesty and Embarrassment in China

Chinese often appear shy and self conscious to Westerners, especially when they are around foreigners or are in situations which they are not used to. Chinese don't like to be separated from crowd, stared at or asked too many personal questions (even though they often stare at and ask personal questions of Westerners).

Chinese often smile or giggle when a sensitive subject is broached or they feel embarrassed or uncomfortable. When young Chinese are asked if they have a girlfriend they usually laugh and look away. Chinese often grin when something bad has happened. Laughing loudly is often a sign of uneasiness. The writer Peter Hessler described the “the Chinese grin of embarrassment” as “the kind of expression that make your pulse quicken.” Many Chinese will give a broad smile when they make eye contact with a stranger and then frown when they look away.

Chinese generally don’t express their feelings very well. The American-born Taiwan-raised film director Bertha Bay-Sa Pan told the New York Times, ‘The Chinese are not very expressive. We don’t tend to say, “I love you,” even to our families, and we’re not physically affectionate.” At the same time some Chinese can be very self-deprecating. It is not unusual for a man to introduce himself as “Hu, a silly old pig.”

Successful Chinese are often very modest. Most of China’s super rich are publicity-shy. They rarely grant interviews and little is known about them. When they do talk they tend to talk more about their $2 haircuts than lavish possessions. Perhaps they are reminded of the old Chinese proverb: Fame portends trouble for men, just as fattening does a pig.

Formality, Punctuality and Apologizing in China

Chinese tend to be very formal and have an us versus them attitude towards outsiders. Their formality persists until one is allowed on the inside of their group, which is something that usually takes place over time and requires following established protocol and recognizing hierarchies and showing proper respect to achieve.

Chinese tend to be very formal and have an us versus them attitude towards outsiders. Their formality persists until one is allowed on the inside of their group, which is something that usually takes place over time and requires following established protocol and recognizing hierarchies and showing proper respect to achieve.

Apologizing is important in China. The methods, manners and the ways it is carried out is affected by the rank and identity of the person doing the apologizing and the person being apologized to and is often conducted in a way that is difficult for Westerners to unravel and comprehend.

Chinese find it difficult and humiliating to apologize to someone face to face. Sometimes they refuse to apologize even when they know they are wrong. Refusing to apologize causes great harm because of concerns about losing face. In some places in China, there are apologist-for-hire businesses that allow people to hire a stranger to say I'm sorry to someone they wish to apologize to. The enterprises began in 2000 in Nanjing and have spread to Beijing and other cities.

The Chinese have a strong sense of punctuality. See Social Customs.

Indirectness and Uncertainty in China

Chinese can also be very indirect, sometimes painfully so, especially when talking about something that bothers them or may cause them to look bad. Chinese, for example, consider it rude to ask for something directly and tend to avoid using questions that have a yes or no answer to avoid putting someone in the position where they might have to give an answer they don't want to give or hurt someone's feelings. Even inquiring about directions can be perceived as impolite because the person who is asked directions may not know where the place is and this could cause them to feel embarrassed or uncomfortable.

Chinese have a high tolerance for uncertainty, Many feel comfortable and even thrive in it. A book editor told the Los Angeles Times. “After a while it becomes quite normal.”. One Chinese man who returned to China after many years in the United States, told the Washington Post, “People think in a more complicated way. I’m more straightforward now, but they’re all zigzagging.” A prominent architect said, “We could do much better if we could think more. But you don’t have so much time for thinking.”

Arthur Henderson Smith wrote in “Chinese Characteristics”: “One of the intellectual habits upon which we Anglo-Saxons pride ourselves most, is that of going directly to the marrow of a subject, and when we have reached it, saying exactly what we mean. No very long acquaintance is required with any Asiatic race, however, to satisfy us, that their instincts and ours are by no means the same — in fact that they are at opposite poles. We shall lay no stress upon the redundancy of honorific terms in all Asiatic languages with which we happen to be acquainted some of which in this respect, are indefinitely more elaborate than the Chinese. Neither do we emphasize the use of circumlocutions, periphrases, and what may be termed aliases, to express ideas which are perfectly simple, but which no one wishes to express with simplicity. Thus a great variety of terms may be used in Chinese to indicate that a person has died, and not One of the expressions is guilty of the brutality. [Source:“Chinese Characteristics” by Arthur Henderson Smith, 1894]

“No extended experience of the Chinese is required to enable a foreigner to arrive at the conclusion that it is impossible from merely hearing what a Chinese says, to tell what he means. This continues to be true, no matter how proficient one may have become in the colloquial.The reason of this must of course be that the speaker did not express what he had in mind, but something else more or less cognate to it, from which he wished his meaning or a part of it to be inferred.

“Next to a competent knowledge of the Chinese language,' large powers of inference are essential to anyone who is to deal successfully with the Chinese, and whatever his powers in this direction may be, in many instances he will still go astray, because these powers were not equal to what was required of them.“The individual who has done you a favor, for which it was impossible to arrange at the time a money payment, politely but firmly declines the gratuity which you think it right to send him in token of your obligation. What he says is that it would violate all the Five Constant Virtues for him to accept anything of you for such an insignificant service, and that you wrong him by offering it, and would disgrace him by insisting on his acceptance of it. What does this mean? It means that his hopes of what you would give him were blighted by the smallness of the amount; and that like Oliver Twist, he ''wants more.'' And yet it. may not mean this after all, but may be an intimation,' that there is something else which happens at the time to be morel serviceable to him than your money, and which he must give up hoping for if he takes the money. Or it is possible, that the real meaning is, that though the money is desirable, there is I a probability that you will at some future time have it in your power to give him something which will be even more desirable, to the acquisition of which the present payment would be a bar, so that he prefers to leave it an open question, till such time as his own best move is obvious. '

“It is an example of the Chinese talent for indirection, that owing to their complex ceremonial code, one is able to show great disrespect for another, by methods which to us seem preposterously oblique. The manner of folding a letter, for example, may embody a studied affront. The omission to raise a Chinese character above the line of other characters, may be a greater indignity than it would be in English to spell the name of a person without capital letters. In social intercourse, rudeness may be offered, without the utterance of a word to which exception could be taken; as by not meeting an entering guest, at the proper point, or by neglecting to escort him the distance suited to his condition; The omission by anyone of a multitude of ' simple acts may convey a thinly disguised insult, instantly recognized as such by a Chinese.

Liu Bolin, China’s Invisible Man artist

Lying and Honesty in China

People in China lie all the time about this and that. Teenagers lie about their age to get jobs. Workers lie when they are negotiating so they can a better job. The Chinese do a great deal of communicating thorough symbolic expression, hints and allusions, expecting listeners and readers to grasp the meaning by reading between the lines. The Chinese like to say, “He who says the least says the most.” One Chinese man told the Los Angeles Times, "Chinese thinking is different from Western thinking. Westerners try to get at things very clearly, asking what, why and how much. Chinese are more interested in dealing with things using metaphors or intuitive comparisons."

In 1899, Arthur Henderson Smith wrote in “Village Life in China”: “To affirm that every Chinese is a natural liar is a grievous error. On the contrary we believe the Chinese to be by far the most truthful of Asiatics. Yet there can be no doubt that disingenuousness is to them a second nature. It runs through the warp and woof of their life. [Source: “Village Life in China” by Arthur Henderson Smith, Fleming H. Revell Company, 1899, The Project Gutenberg]

“A witness in a Chinese lawsuit (where veracity is more than ordinarily important) usually begins his mixture of three-tenths fact with seven-tenths fiction with the remark: “I will not deceive Your Honour.” In this he speaks the truth, for His Honour knows perfectly well that the witness is lying, and the witness knows that His Honour knows it. The only question is in regard to the percentage of falsehood, and as to which particular statements come under that head. The same principles are in operation in the family life as in court. Most husbands know better than to confide the real state of their affairs to their wives. Children in turn constantly conceal from their parents what ought to be known, and are themselves deceived whenever it becomes convenient to do so. A Chinese woman known to the writer when a mere child was one day told by her mother that she must not go upon the street to play as usual, but must remain in the house and have her clothes changed. This was done, and before she knew it, she was thrust into a sedan-chair, and was on the way to the house of her “husband,” for this was her marriage! The conditions which would make such an occurrence possible, would produce quite naturally many phenomena of a disagreeable description. It is a popular adage that “She who knows how to behave as a daughter-in-law will prevaricate at both her homes, while the inexpert daughter-in-law reveals what she knows at each of them” — and is in constant trouble in consequence.

Perseverance and Endurance in China

Many Chinese are very tough and have endured hard lives (See Labor, Cultural Revolution). The editor mentioned above told the Los Angeles Times, “While life for ordinary people is hard it also makes them strong and determined to survive.” It also makes them exhausted. Arthur Henderson Smith wrote in “Chinese Characteristics” in 1894: “Among a dense population like that of the Chinese Empire, life is often reduced to its very lowest terms, and those terms are literally a “struggle for existence." In order to live, it is necessary to have the means of leaving, and those means each must obtain for himself, as best he can. Deep poverty and a hard struggle for the means of existence will of themselves never make any human being industrious, but if a man or a race is endowed with the instinct of industry, these are the conditions which will tend most effectually to develop industry. The same conditions will also tend to the development of economy, which, as we have seen, is a prominent Chinese quality. These conditions also develop patience and perseverance. [Source:“Chinese Characteristics” by Arthur Henderson Smith, 1894]

The Chinese have been hunting for a living under conditions frequently the most adverse, and they have thus learned to combine the active industry with passive patience. The Chinese are willing to labour for a very long period of time, for very small rewards, because small rewards are much better than none. Ages of experience have taught them that it is very difficult to make industry a stepping stone to those opportunities. The Chinese is content to toil on for such rewards as he may be able to get, and in this contentment, he illustrates his virtue of patience.

It is in his staying qualities that the Chinese excels the world. Of that quiet persistence which impels a Chinese student to keep on year after year attending the examinations, until, he either takes his degree at the age of ninety, or dies in the effort, mention has been already made. No rewards that are likely to ensue, nor any that are possible, will of themselves account for this extraordinary perseverance. It is a part of that innate endowment with which the Chinese are equipped, and is analogous to the fleetness of the deer, or the keen sight of the eagle. A similar quality is observed in the meanest beggar at a shop door. He is not a welcome visitor, albeit so frequent in his appearances. But his patience is unfailing, and his perseverance invariably wins its modest reward, a single brass cash.

The Chinese bear their ills, not only with fortitude, but what is often far more difficult, with patience. A Chinese who had lost the use of both eyes, applied to a foreign physician to know if the sight could be restored, adding simply, that if it could not be restored, he should stop being anxious about it. The physician told him that nothing could be done, upon which the man remarked, “Then my heart is at ease.'' His was not what we call resignation, much less the indifference of despair, but merely the quality which enables us to "bear the ills we have.

Eating Bitterness

The expression “eating bitter” describes putting up with hardships. One Chinese businessman told the Los Angeles Times, “If you have any problems, you go to your parents. And if your parents can’t help you, you bear them yourself.” Enduring and eating bitter are virtues highlighted by the Communists in the Long March and living in the countryside during the Cultural Revolution. In modern China, people seem willing to tolerate unfairness and bitterness as long as their standard of living improves.

Asian societies have traditionally put an emphasis on maintaining a stiff upper lip, remaining strong and getting over problems rather than talking about them. Those that seek help are often stigmatized as weak or crazy. Psychology, psychiatry and counseling are rather new fields in China, where Confucian hierarchy has traditionally provided stability and people didn’t talk much about their feelings. “Chinese traditionally don’t like to articulate their emotions,” one psychologist told the Los Angeles Times.

Self-sacrifice has long been esteemed as a righteous virtue in China. It ties in with collectivism.a trait valued by both Chinese and Communists, in which a person puts the group before he individual and nobly illustrated by a teacher putting the interests of his students before his own.

Joseph Kahn wrote in the, New York Times, “As told in the magnum opus of ancient Chinese history, “Records of the Grand Historian,” King Goujian knew how to nurse a grievance. At the start of his reign in the fifth century B.C., Goujian’s archenemy attacked his kingdom, captured Goujian and made him a slave. The king was granted amnesty after three years and allowed to reclaim his throne. But Goujian swore off the trappings of monarchy, eating peasant food and living simply. He slept on a bed of brushwood and dangled a gallbladder from the ceiling, licking it to taste its bitterness every day. A Chinese aphorism, “sleeping on sticks and tasting gall,” celebrates his determination to remember the shame and humiliation he suffered — and to draw strength from it. [Source: Joseph Kahn, New York Times, July 18, 2013]

In 1899, Arthur Henderson Smith wrote in “Village Life in China”: ““The Chinese character often abounds in amiable alleviations of conditions which would seem at first sight to make existence intolerable. In the breasts of the Chinese, as in ours, Hope springs eternal. His generalizations from the experience of others as well as his own, render him measurably certain that in the long-run almost nothing will go right. He expects to meet insincerity, suspicion, and neglect, and he is rarely disappointed. He will often be dependent upon those who would be glad to get rid of him, and who keep him constantly aware of this fact. He knows as certainly before as after the event that the loans which he is obliged to make will not be repaid at the proper time, nor in full; that the promised assistance if given at all will be rendered grudgingly, and perhaps turned into open hostility. It is proverbial that he has in his mind “two hundred next years” but he is not infrequently perfectly aware that no number of “next years” will ever suffice to get him straight with the world. Yet amid all this he generally maintains a serene cheerfulness which to us would be as impossible as comfortable respiration in the foul atmosphere of a Chinese sleeping-room. He is used to it — we are not. A man of this type weighted with a termagant wife, who had become exasperated by the unexpected remarriage of a brother of her husband for twenty years a widower, and who filled the house with a tempest in consequence, said to the writer that for the past three months he had not drawn “one peaceful breath!” This was not mentioned by way of complaint, but as one might refer in reply to an inquiry about a troublesome corn on the toe. Under stress of this sort many Chinese exhibit a degree of forbearance to which it is to be feared we have no counterpart in the West, where individual rights have not for ages been merged in those of the family. Such persons are said to “eat a dumb man’s injury,” and the number of them is proverbially unlimited, for the class is immortal. [Source: “Village Life in China” by Arthur Henderson Smith, Fleming H. Revell Company, 1899, The Project Gutenberg]

“No one who is intimately acquainted with their real life is likely to exaggerate the evils from which the Chinese suffer, since the strongest representation often seems to come short of the truth. But every one finds himself asking by what means it would be possible to forefend some of these evils. Since many of them appear to be inseparably associated with that poverty which is apparently the keynote of Chinese discords, one is tempted to imagine that if poverty were abolished, family disunity also would largely disappear. Something may be said in favor of this theory, but it fails in presence of the undoubted fact that the evils to be remedied are perhaps quite as prevalent among those Chinese who are fairly well off, as among the poor, besides being much more conspicuous and irrepressible.

Patience without Complaining in China

Chinese generally don’t complain. In a 1997 survey by the Leo Burnett ad agency, 57 percent of Chinese agreed that people should not voice complaints (compared to 4 percent among Americans). Presumably this is at least partly the result of enduring so much hardship and possibly winding up in serious trouble if you do complain." Arthur Henderson Smith wrote in “Chinese Characteristics”: “ “The term patience embraces three quite different meanings. It is the act or quality of expecting long, without complaint, anger or discontent. It is the power or the act of suffering or bearing quietly or with equanimity any evil — calm endurance. It is also employed as a synonym of perseverance. The quality of Chinese patience, which to us seems the most noteworthy of all — its capacity to wait without complaint, and to bear with calm endurance. [Source:“Chinese Characteristics” by Arthur Henderson Smith, 1894]

The writer once saw about one hundred and fifty Chinese, most of whom had come several miles in order to be present at a feast, meet a cruel disappointment. Instead of being able as was expected to sit down at about ten o'clock to the feast, which was for many of them the first meal of the day, owing to a combination of unforeseen circumstances, they were compelled to stand aside, and act as waiters on about as many more individuals who ate with that relish and deliberation which is a trait of Chinese civilization in which it is far in advance of our own. Before the meal for which they had so long and so patiently waited could be served, another delay became necessary, as unforeseen as the first, and far more exasperating. What did these hundred and fifty outraged persons do? If they had been inhabitants of the British Isles, or even of some other portions of "nominally Christian lands," we know very well what they would have done. They would have worn looks of sour discontent and growl at their luck.... The hundred and fifty Chinese did nothing whatever of the sort, and were not only good tempered all day, but repeatedly observed to their hosts with evident sincerity and with true politeness, that it was of no consequence whatever that they had to wait, and that one time was to them exactly as good as. another! Does the reader happen to know of any form of Occidental civilization which would have stood such a sudden and severe strain as that?

“The exhibition of Chinese patience which is likely to make the strongest impression upon a foreigner, is that which is unfortunately so often to be seen in all parts of the Empire, when the calamities to which reference has just been made, have been realized upon an enormous scale. The provinces of China with which foreigners are most familiar, are seldom altogether free from disasters due to flood, drought, and resultant famine.While it is true that relief is extended in a certain way, in some large cities, and where the poor sufferers are most congregated, it is also true that this relief is limited in quantity, brief in duration, and does not provide the smallest remedy for more than a minute percentage of even the worst distress.

When the disaster comes, it is therefore accepted as alike inevitable and remediless. If those who are overtaken by it, can trundle their families on wheelbarrows off to some region where a bare subsistence can be begged, they will do that. If the family cannot be kept together, they will disperse, picking up what they can, and reuniting if they succeed in pulling through the distress. If no relief is to be had near at hand, whole caravans will beg their way a journey of a thousand miles in mid-winter to some province where they hope to find that the crops have been better, that labour is more in demand, and that the chances of survival are greater. If the floods have abated, the mendicant farmer returns to his home long enough to scratch a crack in the mud while it is still too soft to bear the weight of an animal for ploughing, and in this tiny rift he deftly drops a little seed wheat, and again goes his devious way, begging a subsistence until his small harvest shall be ripe. If Providence favors him, he becomes once more a farmer, and no longer a beggar, but with the distinctly recognized possibility of ruin and starvation never far away.

It is well for the Chinese that they are gifted with the capacity not to worry, There are comparatively few who do not have some very practical reason for deep anxiety. Vast districts of this fertile Empire are periodically subject to drought, flood, and in consequence, to famine. Social calamities, such as law-suits, and disasters even more dreaded, because indefinite, overhang the head of thousands, but this fact would never be discovered by the observer. We have often asked a Chinese, whose possession of his land, his house, and sometimes of his wife was disputed", what the outcome would be. "There will never be any peace, '; is a common reply. "And when will the matter come to a head?" "Who knows?" is the frequent answer, "it may be early or it may be late, but there is sure to be trouble in plenty." For life under such conditions what can be a better outfit than an infinite capacity for patience?

Risk, Success, and Competition in China

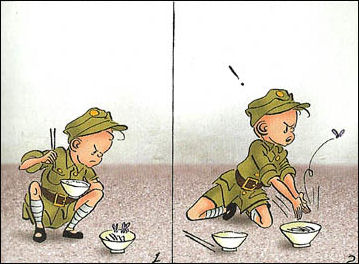

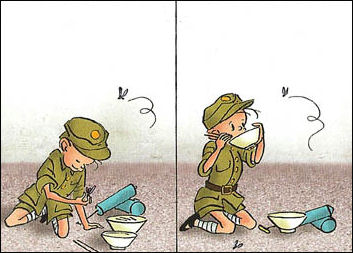

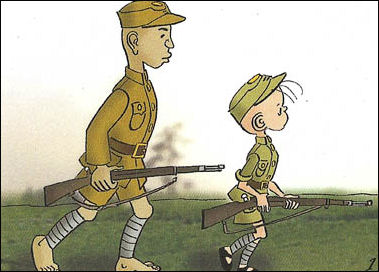

Sanmao comic

In the West risk takers are generally praised as people with ambition and drive while in China they are often viewed as overly emotional and careless. But that isn't to say Chinese don't take risks. They also invest heavily in the stock market and like to gamble. They also have a strong entrepreneurial spirit and powerful desire to succeed in business. If they fail at one thing they try something else.

Chinese can be very competitive. They are very serious about games and will do anything to the win. One Uighur man told the New Yorker that Chinese never fight fair: “It’s not because of their culture, and it’s not because of their history. It comes from something inside their blood.”

It traditionally has been considered to be in bad taste in China to come across as too ambitious Many Chinese today however are obsessed with achieving success. Peter Hessler wrote on National Geographic that he found the following slogans inscribed next to a worker’s bed: “Find success immediately,” “Face the future directly,” and “A person can become successful anywhere; I swear I won’t return home until I am famous.”

The Chinese used to say friendship first, competition second but this view is changing as individual and self development become more developed.

One Chinese chatline user said, China “is an unusual society. Many Chinese like to shift responsibility and duty to others. If that person succeeds, he is revered. If the opposite happens, he will be condemned.”

Speed and Change

Sanmao comic

The pace of life is very quick. Chinese get off planes very fast. Elevators doors close almost before you have time to step out. Jonathan Franzen wrote in The New Yorker, one difference between Shanghai and New York “was the alacrity with which the tiniest advantage was seized, the slightest hesitation exploited. Even more striking, though, was the self-blinkering angle at which the women pushing around me...held their head. It was the angle of looking at the ground exactly one step ahead.

Speed is of essence, lest one gets left behind. The term “Chinese time” sometimes is used to describe the breakneck pace in whcih things are done and chnage in China. Mao Jian, a Shanghai-based writer wrote in the Washington Post, “ Sizzling in the wok is not stuffed buns, but hearts beating fast, faster and faster still. Got to speed up to make a buck. Tear down the old courtyard, fill in Suzhou Creek, race to register that domain name. One day late is forever late. Overnight a fairy sprinkles her pixie dust and that corner shed turns into an idyllic café. But when you walk in, you see the owner reading a how-to-guide on opening a restaurant. Yet another new idea sprouting. Longevity is not the goal; speed is the style in China today.”

The developer Zhang Xin told The New Yorker, “Chinese people don’t like anything old—they want everything new. If someone came from th moon, they would think is a newer country than America...Maybe that is what Mao wanted.

Peter Hessler wrote in The New Yorker,”The place changes too fast; nobody in China has the luxury of being confident in his knowledge. Who shows a peasant how to find a factory job” How does a former Maoist learn to start a business”...Everything is figured out n the fly; the people are masters of improvisation.”

Peter Hessler wrote in National Geographic, “Few Chinese spend much time thinking about the future. Decades of political turmoil taught citizens that nothing lasts forever, which inspires the fearlessness of the entrepreneurs but also makes them shortsighted.”

China Daily: Why the Rush?

Sanmao comic After the Wenzhou high-speed train crash in July 2011 that left 40 people dead Raymond Zhou wrote in the China Daily, “ For three decades, China has prided itself on its mantra of "faster and higher". Our GDP overshoots others by many times. Our high-rises pop up as if powered by testosterone. Our cityscape takes on new forms every few years. We had been stagnant for too long. We have to catch up. We don't want to be left behind in this era of globalization.” [Source: Raymond Zhou, China Daily, August 4, 2011]

In this madness for speed, we tend to forget that faster and higher do not necessarily equal better. Of course, living standards have risen for most of us, but if we stop to contemplate the costs, we will be shocked. Besides the environmental costs, there is the unaccounted-for price of mental health that is often left out of the equation. When we feel dizzy by the world that is whizzing by, when we get nostalgic about the simple life we used to lead in dilapidated homes (which was actually not that good, if one is objective), it could be signs that growth is a bit too fast for comfort.

We Chinese always want to get ahead of the neighbor. If our neighbor's kid has a score of 98, we want ours to get 99 or 100. Does the higher score reflect his or her higher ability? We don't really care that much. On a national level, we want to accumulate the biggest tally of gold medals at the Olympics. Does that speak of the bigger picture of the country's fitness and sports? It's just an afterthought.

We even want to have all those trivial and strange conquests that belong to the realm of Guinness World Records - not for fun, mind you, but for bragging rights. We are pursuing speed for the sake of speed, or for the sake of vanity. Other countries also try to "keep up with the Joneses", but nowhere is this as pronounced and concerted as here in China where it is an obsession - from the highest official to the lowest footman.

Sanmao comic In this relentless drive for growth and wealth, collisions are bound to occur. Of these, the one between development and a citizen's right to their homestead is probably the most acute, and the one between development and the ecology, the most sustained. The old order is crumbling, and the new is not yet ready. There is a vacuum that scamsters and demagogues are only too happy to fill.

Rules and regulations are often tossed aside as an inconvenience. Look at this report from last year from the Railway Ministry's own newspaper: Some German specialists were hired to train the drivers of bullet trains. They said they needed three months to complete a training course. But they were told they had only 10 days to do the job. It became the ego trip of the rail department that they could turn out drivers in 10 days while in Germany they needed as long as three months, to the extent this report was spread far and wide as a token of its achievement.

Who benefits from such haste? Surely, not the passengers. Realistically, it enhances only the self-glorification of a few people and departments.High speeds will take us to our destinations in a shorter time. But not every trip is intended to save time. We take a ramble in a park at a leisurely pace...We don't really need the frenzy of non-stop acceleration, especially when higher speed comes at higher risks to safety. Accidents are sadly unavoidable. But that is no excuse for those errors that occur as a consequence of lax management or under-tested facilities.

It is time we paused to reflect on the purpose of the journey that is life.When we slow down, we'll notice that life is not always a car race. Our skyline may take on new shapes, but our conscience should remain in shape. Our trains may derail, but many of us tenaciously hold on to our old morality, our sense of good versus evil.

Chasing Fortune, Truth, and Faith in the New China

In a review of the book: “Age of Ambition: Chasing Fortune, Truth, and Faith in the New China” by Evan Osnos, John Pomfret wrote in the Washington Post,“Two themes drive this compelling and accessible investigation of the modern Middle Kingdom. The first is hunger. China is living through “a ravenous era,” Osnos declares early in the book. And it’s a hunger not just for meat — the consumption of which has increased sixfold since the 1970s. After 40 years of dead-end Maoism, Chinese are combing the globe for commodities, wealth, experiences and respect. The second theme is the chase. “All over China people were embarking on journeys, joining the largest migration in human history,” Osnos writes, and he doesn’t mean that just in physical terms. He peppers the book with tales of characters making spiritual, economic, emotional and philosophical expeditions that have transformed their lives and the world as we know it. [Source: John Pomfret, Washington Post, May 16, 2014. John Pomfret, the author of “Chinese Lessons: Five Classmates and the Story of the New China” /*]

“And it all has happened so fast. As Osnos notes, the 1980 edition of China’s authoritative dictionary, “The Sea of Words,” described individualism as “the heart of the Bourgeois worldview, behavior that benefits oneself at the expense of others.” But today Chinese have embraced the idea that they can be the agents of their own fate with an alacrity that perhaps only an American observer can really understand. Dividing the book into three sections, Osnos depicts the pursuit of wealth, freedom and something to believe in. Along the way the reader is treated to a series of finely wrought portraits of Chinese searchers. We meet Lin Yifu, who as a young officer in the army on Taiwan makes the remarkable decision to swim to China in 1979, then earn a doctorate in economics at the University of Chicago and, as the World Bank’s chief economist, become one of the principal cheerleaders of China’s hybrid economic model of unfettered capitalism and state control. /*\

“There’s Gong Hainan, a peasant who founded a dating Web site in a typical rags-to-riches story that has become central to China’s sense of itself. Tang Jie is a philosophy student at a leading university in Shanghai whose problems with the Western media’s portrayal of China’s treatment of Tibet give Osnos a way to explore the critically important world of Chinese nationalism and its fixation that the West is out to get China. The prominent dissidents Ai Weiwei and Liu Xiaobo also receive deeply insightful treatment. In all, Osnos ranges omnivorously between rich and poor, Christians and Buddhists, the patriotic and the oppressed, moguls and Mafiosi, democrats, dissidents and dogged supporters of the regime. /*\

“Osnos’s examination of Chinese ambition is... ambitious in revealing the national traits of modern Chinese. While Chinese describe themselves as more cautious than Americans, Osnos notes at one point, psychological research has shown that they take consistently higher risks with their investments than Americans of comparable wealth. In most developing countries, the educational level of parents is a decisive factor in determining how much a child will earn in adulthood; but in China, Osnos writes in another section, “parental connections” — not education — are the key, making urban China one of the least socially mobile places in the world. Osnos’s book brings to mind “Chinese Characteristics,” written by the American missionary Arthur H. Smith in 1894; it was the most widely read book on China well into the 1920s. “Chinese Characteristics” is riddled with the patronizing racism of the time, but it’s also deeply insightful. Smith’s description of the Chinese concept of “face” inspired China’s best-known writer, Lu Xun, to compose his most famous short story, “The True Story of Ah Q.”

“And finally, amid all of China’s frenetic energy and miraculous economic growth, Osnos observes that its Gilded Age is an era without any “central melody”; there’s a huge spiritual hole in the middle of the Chinese soul, and, he argues, it makes that great country’s future uncertain and a bit scary for them and for us.” /*\

Book: “Age of Ambition: Chasing Fortune, Truth, and Faith in the New China” by Evan Osnos, 2014]

Pragmatism, Control and Logic

Sanmao

Some have argued that the influence of Confucianism has caused Chinese to put more trust in traditions and authority over science and method, which Westerners emphasize. While Chinese can be very thoughtful, intuitive and logical, the argument goes, they tend to give more weight to relationships, obligations, loyalties and traditions when making a decision and approach problems in a holistic way rather than in sequential, linear or progressive way, which is the norm in the West.

Even so, Chinese also have a reputation for being quite practical and pragmatic. Peter Hessler told National Geographic,” People seem quite rational—very, very pragmatic...This generation of Chinese: you can pretty much predict how people will respond because they tend to act in their own best interest."

Pearl S. Buck once said; “The Chinese, while not a changeable people, are nevertheless people who are able to change when they see the time has come to change. They are basically practical people. They do not cling to a custom or tradition or even a religion just because it has always been the way. When they see that something no longer works, they change it.”

A survey on preferred ideology taken among students in the northern province of Hebei in 2006 found that 66 percent of them favored pragmatism over communism (favored by 13 percent) and hedonism (favored by 11 percent). Some have argued Chinese pragmatism is rooted in Confucianism.

My wife teaches Chinese exchange students at a university in Japan. She said that many of her students—who grew up in China in the one-child policy, Little Emperors era—have difficulty negotiating and coming to an agreement as a group. She attributes this to growing up without brothers and sisters.

Jackie Chan raised some eyebrows in April 2009 when he said that “Chinese need to be controlled. Before an audience of business leaders on Hainan Island in China he said, “I’m not sure if it’s good to have freedom or not. I’m really confused now. If you’ve got too much freedom you’re like the way Hong Kong is now. It’s very chaotic. Taiwan is also chaotic...I’m gradually beginning to feel that we Chinese need to be controlled. If we’re not being controlled, we’ll just do what we want.”

Chinese Approach to Negotiations

Sanmao

Journalist and China expert James McGregor wrote in the Washington Post, “China is about unity, focus and leverage. Chinese officials and business executives are obsessed with a single question: What advantage do I have over you?”

Henry Kissinger wrote in Newsweek, "China's approach to policy is skeptical and prudent...impersonal, patient and aloof; the Middle Kingdom has a horror of appearing supplicant. Where Washington looks to good faith and good will as the lubricant of international relations, Beijing assumes that statesmen have done their homework, and will understand subtle indirections." The Chinese often "indicate a strong preference, not a condition....To the Chinese, Americans appear erratic and somewhat frivolous."

Beijing takes it time making decisions. Kissinger wrote: "The Chinese maneuver to induce their opposition to propose the Chinese preference so that Chinese acquiescence can appear as the granting of a boon to the interlocutor....When faced with what is considered a legacy of colonialism, China is prone to bully in order to demonstrate its imperviousness to pressure. Any hint of condescension or sign that Chinese territorial integrity is nor being taken seriously evokes strong—and to Americans, seeming excessive—reaction."

One Chinese scholar, who has written extensively about the United States, told Time, "If you treat China as a friend, he will treat you well and will never betray you. Treat him like an enemy and he'll fight back without hesitation."

Chinese Love of Business and Money

Sanmao

In the Mao era Chinese prided themselves on their frugality and desire to serve the people but today that sentiments seems like something from the distant past in fast-paced urban China. One Chinese man told the New York Times, “The things we care about most in China now are money, money, and money.” Another said, "It’s all money-grubbing. Many Chinese have lost their sense or morality and ethics.”

One woman told the New York Times, "Chinese people never talked so much about money before. Now they are always talking about salaries and stocks and joint ventures." One Chinese woman told the Washington Post, “People here don’t want any more Cultural Revolutions or war. We like material things.”

In a poll in the 1990s, 68 percent of the Chinese said their attitude towards life was “ work hard and get rich." Only 4 percent said it was "never think of yourself; give everything in service of society." In a 1997 survey by the Leo Burnett ad: 64 percent of Chinese agreed that making money is most important part of career, compared to 27 percent of Americans. In a survey in China in 2005, nearly three quarters of those asked said that money was the most important thing.

A desire to make money is not something that is deeply rooted in Confucianism. Merchants and businessmen were at the bottom of the Confucian social order. Sons have traditionally been taught to give whatever money they made to their parents.

Seeking wealth has become an end to itself to a point that for many people nothing else matters and many people are spiritually adrift. Yang Yo, a singer who is sometimes called the Bob Dylan of China, told the International Herald Tribune, “Few people in China think about a simple life of following dreams, ideals and knowing who you are. The just sit around talking about how to make more money.”

Chinese Directness, Openess and Earthiness

Sanmao

In some situations Chinese can be very indirect, but in other situations they can be very direct,open and frank to the point of tactlessness. One aspect of Chinese "peasant directness" is that Chinese are not as shy about talking about their feces and urine as Americans. They often excuse themselves from social gatherings by saying the equivalent of "I have to take a shit" or "I have to take a piss" when they have to go the bathroom. When Theroux once asked a Chinese man on the train what he just did, he said, "I vomited in the toilet."

Chinese will sometimes openly laugh at the way foreigners look and dress and make comments about their noses and the way they speak Chinese.

The same is true with feeling. Unlike the Japanese and other Asians who often mask their feelings, the Chinese often not shy about expressing their feelings. One Uighur told the New Yorker, “The Chinese—if they don’t like you, it’s always clear.”

A guidebook for Chinese by Hong-Kong-born London-based Chinese advised his readers: “Don’t ask foreign women how old they are.” Chinese are often ask people they have just met: their age, marital status, how much money they make, and whether or not they have a boyfriend or girlfriend questions that Westerners regards as personal and prying. Chinese ask these questions for a couple of reasons. First all they are curious. Second, they want know a person's age and marital status so they know how to address the person.

See Spitting, Urinating, “Spiritual Civilization” Campaign, Customs

Image Sources: 1) Losing Face, from some blog; 2) drawings from Citizens posters. University of Washington; 3) photgraphs, beifan.com ; Liu Bolin, China’s Invisible Man artist, Global Times Chinese: photo.huanqiu.com ; You Tube

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated September 2021