TIANANMEN SQUARE MASSACRE

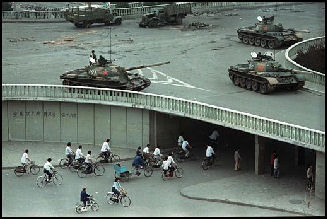

At 2:00am on June 4th 1989, People's Liberation Army tanks and 200,000 soldiers moved into Tiananmen Square in Beijing to crush a large pro-democracy demonstration that had been going on for seven weeks. The tanks rolled over people that got in their way and soldiers opened fire on groups of protesters.

At 2:00am on June 4th 1989, People's Liberation Army tanks and 200,000 soldiers moved into Tiananmen Square in Beijing to crush a large pro-democracy demonstration that had been going on for seven weeks. The tanks rolled over people that got in their way and soldiers opened fire on groups of protesters.

Hundreds of students and supporters were killed. Hospitals were filled with casualties and P.L.A. troops in some cases prevented doctors from treating wounded demonstrators. The figure 2,000 dead is often cited but nobody but the Chinese authorities know how many people really died, partly because the bodies were carried off the night of the massacre and buried in secret graves. Reporters that tried to investigate what happened have been roughed up by soldiers with cattle prods.

Ian Johnson wrote in the New York Review of Books, “On the night of June 3–4, China’s paramount ruler, Deng Xiaoping, and a group of senior leaders unleashed the People’s Liberation Army on Beijing. Ostensibly meant to clear Tiananmen Square of student protesters, it was actually a bloody show of force, a warning that the government would not tolerate outright opposition to its rule. By then, protests had spread to more than eighty cities across China, with many thousands of demonstrators calling for some sort of more open, democratic political system that would end the corruption, privilege, and brutality of Communist rule. The massacre in Beijing and government led violence in many other cities were also a reminder that the Communist Party’s power grew out of the barrel of a gun. [Source: Ian Johnson, New York Review of Books, June 5, 2014]

Liao Yiwu wrote in his poem“Massacre”:“Shoot through their skulls! Scorch them! Let their juice burst out. Let their souls burst out. Squirt it on the traffic bridges, on the tower, on the railings! Let it splatter on the road! Shoot it into the sky and make stars! The stars are running away! The stars are growing legs, running away! Heaven and earth turning around. All humanity wearing shiny hats. Shiny, shiny steel helmets. An army group storming out of the moon! Shoot! Strafe! Shoot! This is great! People and stars falling together. Running together. Don’t know each other. Chase them into the clouds! Chase them until the earth opens, shoot and shoot into their flesh! Make another hole for the soul! Another hole for the stars! …” [Source:Liao Yiwu, NY Review of Books, June 3, 2014, Translated by Martin Winter]

The massacre at Tiananmen Square didn't take place in Tiananmen Square but rather in the streets around it. Most of violence occurred on the Avenue of Eternal Peace on the southern side of the square and the Muxidi intersection in western Beijing. Reports that the square was washed in blood were unfounded and it appears no one actually died within Tiananmen Square itself. Crackdowns also occurred in more than 200 cities all over China. What occurred in these places is still largely unknown.

The Chinese government death figure is 200. Other estimates range from 2,700 to much higher. It seems that most of those killed were not student protesters but ordinary Beijing citizens, many of whom happened to be in the wrong place at the wrong time. Among them were many bystanders, including a 17-year-old high school student, a 27-year-old chemistry teacher, and a 30-year-old computer company employee who had been married for only a month.

Good Websites and Sources on the Tiananmen Square Protests: ; Tiananmen Square Documents gwu.edu/ ; Wikipedia article Wikipedia ; BBC Eyewitness Account news.bbc.co.uk Film: "The Gate of Heavenly Peace" has been praised for its balanced treatment of the Tiananmen Square Incident. Gate of Heavenly Peace tsquare.tv.

RELATED ARTICLES IN THIS WEBSITE: TIANANMEN SQUARE MASSACRE: EYEWITNESS ACCOUNTS AND SURVIVOR STORIES factsanddetails.com ; AFTER MAO factsanddetails.com; CHINA UNDER DENG XIAOPING: POLICIES, SPEECHES, SLOGANS AND POLITICS factsanddetails.com; POLITICAL REFORM AND SOCIALIST DEMOCRACY UNDER DENG XIAOPING factsanddetails.com; TIANANMEN SQUARE DEMONSTRATIONS, 1989 factsanddetails.com; DECISIONS BEHIND THE TIANANMEN SQUARE MASSACRE factsanddetails.com; TIANANMEN SQUARE AFTERMATH, IMPACT AND LEGACY factsanddetails.com TIANANMEN SQUARE POLITICAL ACTIVISTS AND PRISONERS factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: “Quelling the People: The Military Suppression of the Beijing Democracy Movement” by Timothy Brook, regarded as the most complete book on Tiananmen Square Amazon.com; “The Tiananmen Papers” by Zhao Ziyang Amazon.com; “Inconvenient Memories: A Personal Account of the Tiananmen Square Incident and the China Before and After” by Anna Wang, Lisa Cordileone, et al. Amazon.com; “Tiananmen Square : The Making of a Protest” by Vijay Gokhale Amazon.com; “Tiananmen Exiles: Voices of the Struggle for Democracy in China (Palgrave Studies in Oral History) by Rowena Xiaoqing He Amazon.com; “The People's Republic of Amnesia: Tiananmen Revisited Illustrated Edition” by Louisa Lim Amazon.com; “Tiananmen 1989: Our Shattered Hopes” by Lun Zhang, Adrien Gombeaud Amazon.com; Amazon.com; "Deng Xiaoping and the Transformation of China" by Ezra F. Vogel (Belknap/Harvard University, 2011) Amazon.com; "Deng Xiaoping and the Chinese Revolution: A Political Biography" by David S.G. Goodman (1994, Routledge) Amazon.com;

Books and Films About Tiananmen Square

“Quelling the People: The Military Suppression of the Beijing Democracy Movement” by Timothy Brook is regarded as the most complete book on Tiananmen Square. According to Ian Johnson it is “a work by a classically trained historian who turned his powers of analysis and fact-digging on the massacre. Even though Brook’s book doesn’t include some important works published in the 2000s (especially the memoirs of then Party secretary Zhao Ziyang and a compilation of leaked documents known as The Tiananmen Papers). Quelling the People remains the best one-volume history of the events in Beijing.” One should also note the works of Wu Renhua, a Tiananmen participant and author of several Chinese-language works, as well as a a book by Jeremy Brown of Simon Fraser University.

According to Australia National University: “The Gate of Heavenly Peace” Directed by Carma Hinton and Richard Gordon; written by Geremie Barmé and John Crowley (1995) is a three-hour documentary film about the 1989 protests in Tiananmen Square that culminated in the violent government massacre on 3-4 June, The Gate of Heavenly Peace interweaves archival footage and contemporary interviews to examine how the protest movement was shaped by the complex political history of China’s twentieth century. The wide range of people interviewed by the filmmakers, including students, intellectuals, workers and government officials, offers a multi-perspectival oral history of the event’s politics and experiences, and provides an insightful analysis of the movement’s promise and legacy. Among those interviewed are public intellectuals Liu Xiaobo and Dai Qing, student leaders Wang Dan, Wuer Kaixi, Chai Ling, and Feng Congde, and workers’ leader Han Dongfang. Now a key reference work on the subject, this is a must-see for those interested in China’s public life, political history and popular movements.

“Sunless Days”, directed by Shu Kei (a.k.a Kenneth Ip, 1990): “Unwilling to make the sort of news reportage that was being continuously aired following June 4, in Sunless Days, director Shu Kei turns to his family and friends, producing a very personal document of what the Tiananmen Massacre means, particularly from the perspective of Hong Kong, with the 1997 handover looming. Speaking to Chinese both in Hong Kong and overseas, in Australia and Canada for example, this filmic essay intermingles poetic reflection with documentary interviews and archival news footage, to give sensitive, frank and insightful account of the greater impact of Beijing’s crackdown on the protest movement beyond the 1989 borders of the People’s Republic, to a global Chinese community. Winner of the OCIC Award at the 1990 Berlin Film Festival.

Events Before the Tiananmen Square Massacre

On April 15, 1989, the popular reformer Hu Yaobang died of a heart attack. According to the “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Nations”: Students in Beijing, who had been planning to commemorate the 70th anniversary of the May Fourth Movement, responded with a demonstration, ostensibly in mourning for Hu, demanding a more democratic government and a freer press. Student marches continued and spread to other major cities. The urban population, unhappy with high inflation and the extent of corruption, largely supported the students and, by 17 May, Beijing demonstrations reached the size of one million people, including journalists, other salaried workers, private entrepreneurs and a tiny independent workers' organization, as well as students. [Source: Worldmark Encyclopedia of Nations, Thomson Gale, 2007]

Deng and the Elders ordered that an editorial be placed in the People’s Daily accusing the students of causing “turmoil,” a word only used in serious situations. The high ranking Communist leader Wang Zhen, one of the Elders, said, "We’ve got to do it, or the common people will rebel...These people are really asking for it. They should be nabbed as soon as they pop out again. Give 'em no mercy...Anybody who tries to overthrown the Communist Party deserves death and no burial?

On May 19, martial law was declared. Zhao was replaced with Jiang Zemin, then a Shanghai official known as being able but compliant. Thousands of military vehicles, including tanks and armored personnel carriers, began moving into Beijing. Rumors began circulating about splits in the Communist leadership, army units that planned to disobey orders and side with the students; and immanence of civil war.

On May 27th, some student leaders announced a retreat. In his book China Live, CNN correspondent Mike Chinoy said the 1989 demonstrators stayed too long in Tiananmen Square. "Why didn't they just declare victory and go home?" he wrote.

But activities continued. On May 29th, five days before the massacre students from the Beijing Art Institute raised a 30-foot-high statue called the Goddess of Democracy, which was model after the Statue of Liberty, near the Monument of People's Heroes at the center of the square. By that time some 3,000 demonstrators staged a pro-democracy hunger strike. On June 2nd there was a rock concert and soldiers began moving in.

Troops came from various cities around China and took up positions on the outskirts of Beijing. On June 3rd orders came to drive through the city and clear the square. Thousands of armed soldiers in open-back trucks and tanks began closing in around Tiananmen Square from the east, north and west.Heading towards the square some military units were blocked by barricades. Some soldiers have said bricks and rocks were thrown and they were shot at by unknown shooters. One soldier said soldiers fired over the head of civilians as a warning.

On the evening of June 3, only about 4,000 demonstrators, most of them students, were left in Tiananmen Square. The others had mostly gotten bored and went home. Some of those who remained squabbled over whether they should leave or hold their ground and die as martyrs. The scene was very tense, in the words of some: “hysterical.”

Chinese government authorities sent in military troops and security police who stormed through Tiananmen Square, trying to clear it. The clearing of Tiananmen Square covered roughly 22 hours from around noon on June 3, 1989, to just past 10 a.m. on June 4.

Before the Tiananmen Square Massacre

Describing the scene on the streets around the Tiananmen Square, the writer Yu Hua wrote in the New York Times, “The people. Still, it was not the rallies in Tiananmen Square that made me truly understand these words, but an episode one night in late May. Martial law had been declared by that time; students and residents were guarding major intersections to keep out armed troops. [Source: New York Times, May 30 2009, Yu Hua is the author of Brothers. This essay was translated by Allan Barr from the Chinese]

In Beijing in late May, it’s hot at midday but cold at night. I was wearing only a short-sleeved shirt when I set off after lunch, and by late that evening I was chilled to the bone. As I cycled back from the square, an icy wind blew in my face. The streetlights were dark, and only the moon pointed the way ahead. Then as I approached the Hujialou overpass a wave of heat suddenly swept over me, and it only got hotter as I rode further. I heard a song drifting my way, and a bit later I saw lights gleaming in the distance.”

Thousands of people were standing guard on the bridge and the approach roads beneath. They were singing lustily under the night sky: With our flesh and blood we will build a new great wall! The Chinese people have reached the critical hour, compelled to give their final call! Arise, arise, arise! United we stand.”

Although unarmed, they stood steadfast, confident that their bodies alone could block soldiers and ward off tanks. Packed together, they gave off a blast of heat, as though every one of them was a blazing torch. That night I realized that when the people stand as one, their voices carry farther than light and their heat is carried farther still. That, I discovered, is what the people means.”

Liao Yiwu wrote in The Nation: “Government propaganda referred to us as “thugs,” he said. Well, the millions of unarmed “thugs” were up against fully armed military police that night. The government’s tanks and armored vehicles cleared the way, crushing the barricades, and began to fire into the crowd. People started screaming. More shots rang out. More blood. Everywhere you looked, human beings were being mowed down like weeds.” [Source: “All You Want Is Money! All I Want Is Revolution!: Before the Tiananmen Square massacre, everyone loved China; now everyone loves the renminbi” by Liao Yiwu, The Nation, November 17, 2015]

Tiananmen Square During the Massacre

The hunger strikers Zhuo Duo and Hou Dejian decided they would try to negotiate a safe exit for those still in the square. They took a mini van to the north end of the square. Zhuo later told the Times of London, “We had to walk the last 100 meters or so. It was the most frightening moment of my life. I felt as if I was walking into Hell. Everything was dark. Suddenly I heard a tremendous noise. The soldiers were cocking their guns, Someone shouted to us to stand still or they would open fire. We cried out that Hou Deijan had come to negotiate. There was a pause and then about 10 soldiers approached us. I told the officer that we would tell the students to leave, but we needed to know the attitude of the army.” The officer left to consult with his superiors. By ths time soldiers were starting to clear the square by setting fire to pile of debris.

After what seemed like an eternity the officer returned. Zhou said, “He told us that the command post had agreed to our request. We had to leave by the southeast corner of the square and we had to be gone before the deadline for the army to clear the area. No discussion.” Zhuo and Hu returned to the students area and relayed the message. A voice vote was taken among those still there with voices favoring withdrawal being louder than those for staying.

Zhou remained in the square until the end. “I saw everything,” he told the Times. “I was the last to leave. There were no students left in tents on the square.” Dawn was breaking as he left, with the soldiers closing in on him as he was. “I saw a tank drive up and stop just 20 meters away from us. Everyone was crying.” Zhou’s report is consistent with Chinese government claim that no one was killed in Tiananmen square itself.

Tiananmen Square Violence

The worst of the killing took place on on West Chang’an Avenue. PLA tanks charged into a file of students at Liubukou, a large intersection, killing 11 and injuring many. There have been reports from credible sources, that at the time of the June 4 massacre, the PLA had killed students in the parks near Tiananmen—Zhongshan Park and the Worker’s Cultural Palace. Military troops and security police fired indiscriminately into the crowds of protesters. Tanks ran over people. The killing actually continued after June Fourth. There is still some debate on whether anyone actually killed on Tiananmen Square proper. [Source: Wu Renhua, Yaxue Cao, China Change, June 4, 2016 ++]

The first shots were fired around midnight at unarmed civilians about three miles west of the square. For reasons that are still unclear only soldiers in the west began firing. Students that were grouped around the Monument of People's Heroes in Tiananmen Square were petrified by the shooting. Four intellectuals were able to negotiate with an army commander to let the students leave peacefully through the southwest corner of the square. Some students threw rocks and Molotov cocktails. The morning after the street were littered with debris, burnt buses and smashed bicycles.

Student leader Chai Ling later told Newsweek, "The irony is that we were so afraid of every move we made being misinterpreted. We were afraid that if we left to go to the bathroom, people would think we were deserting. I remember 2 a.m. the morning of June 4. The tanks had already finished moving into the square. We were all gathered around the Monument of the People's Heroes. It was all very tense, very emotional. But at the same time, we had to pee. We had this little tent. So my second in command says, 'Can you all move out” The commander in chief has some business to do.' And they moved out and handed me this pot. It was so embarrassing."

According to one period report: “Turmoil ensued, as tens of thousands of the young students tried to escape the rampaging Chinese forces. Other protesters fought back, stoning the attacking troops and overturning and setting fire to military vehicles. Reporters and Western diplomats on the scene estimated that at least 300, and perhaps thousands, of the protesters had been killed and as many as 10,000 were arrested.”

Zheng Yi again: “In the early hours of June 4th, on Chang’an Avenue, just north of the congressional Great Hall of the People, the crowds began to march eastward, attempting to storm into Tiananmen Square in aid of the students who had been surrounded by troops. They clashed with the army outside the square. Linking arms to form a human wall, they advanced slowly, while singing anthems aloud. Time and again, their ranks would be depleted by gunfire, and they would regroup and continue to press forward slowly. Every time dozens of people fell, others would join in to take their place, so that eventually it became clear that the protesters were engaged in an unwinnable tug-of-war with the army. At dawn, the tanks rolled out of Tiananmen Square and took their positions in a row across the street. They revved their engines and began to advance toward the human wall., “Suddenly, one reckless protester simply lay down in the street. Others followed, and soon there were several hundred people lying all across Chang’an Avenue.

“Despite the menacing tank treads, no one fled. The tanks lost this first battle of willpower and courage. The first tank screeched to a halt ‘so suddenly that the streets shuddered, and the top half of the tank lurched forward.’ Eventually, the tanks fired tear-gas bombs at the crowds to disperse them. They then mowed down the protesters who were fleeing the choking yellow smoke, and killed at least a dozen people on the spot. Five young protesters were killed at the southwest corner of Liubuko Junction. Two of them were crushed onto bicycles, their corpses mangled together with the bikes.”

Soldiers at Tiananmen Square

In a review of “The People’s Republic of Amnesia: Tiananmen Revisited” by Louisa Lim, Ian Johnson wrote in the New York Review of Books, “Lim helpfully starts out with a chapter called “Soldier,” which lays out the mechanics of the killing, as told from the perspective of a People’s Liberation Army grunt whose unit was ordered to clear the square. It’s well known that the army bungled clearing the square, first massing troops on the outskirts of town, then only halfheartedly trying to enter Beijing on successive days as crowds of people pleaded with and cajoled the young soldiers not to listen to their commissars’ propaganda and to go back to their barracks. Finally, when the troops were given clear orders to move, they inflicted horrific civilian casualties, which one can interpret—depending on one’s standpoint—as a result of the soldiers’ poor training, their superiors’ crude tactics, or as a deliberate attempt to pacify through terror. [Source: Ian Johnson, New York Review of Books, June 5, 2014 ==]

“Lim brings these broad-brush conclusions to life through her character, a befuddled, brainwashed young man whose unit had to be smuggled into town in transports disguised to look like public buses, while others came in by subway. It was the only way to get his unit past the civilian roadblocks and to spirit the soldiers and weapons into the Great Hall of the People, one of the principal buildings on the square that they used as a launchpad for their assault. In the days following the killing, we learn something even more surprising— how quickly ordinary people began siding with the soldiers, at least in public: “He did not believe this about-face was motivated by fear, but rather by A deep-seated desire—a necessity even—to side with the victors, no matter the cost: “It’s a survival mechanism that people in China have evolved after living under this system for a long time. In order to exist, everything is about following orders from above.” ==

Military Units That Took Part in the Tiananmen Square Massacre

Wu Renhua told China Change: His second book (in Chinese only) “The Martial Law Troops of June Fourth” “is composed of a total of 19 chapters covering each military unit, plus an introductory chapter. The introduction was a comprehensive overview comprised of 14 sections, in which I dealt with questions like how the order to open fire was issued and how many soldiers and police officers died. [Source: Yaxue Cao, China Change, June 3, 2016 ++]

“This book... truly did reveal some specific details about the martial law troops. For example, how many soldiers were part of the martial law troops? Everyone else could only guess without being able to give a precise answer. And which units took part? To that point, there had been no answer. Even I, a first-hand participant who carried out several months of investigation after the events of June Fourth and interviewed a lot of other eyewitnesses from different locations, didn’t know which units took part in the crackdown. People only mentioned the 38th Group Army, the 27th Group Army, and the 15th Airborne Corps—no one knew about the rest. In this book, I was able to answer all of these questions at once.++

“For example, I calculated that around 200,000 troops took part in the martial law forces. And the book gives a more precise number of units that made up the martial law troops. These answers aren’t estimates: they’re precise figures based on evidence. I think the ability to answer these questions is the reason that academics and researchers took note of this book. So, if you go online to places like Wikipedia, the information cited there regarding the martial law troops all comes from that book.” ++

“These numbers come from Chinese official materials. After the Tiananmen massacre, the government engaged in a large-scale propaganda campaign about “suppressing the counterrevolutionary riot,” and handed out a large number of awards to units and individuals in the military, including the 37 “Defenders of the Republic” [Ed: troops who were killed]. I decoded each of the military code designations referred to in these materials, because the PLA’s numerical designations are secret; instead, each military unit from the regiment level and above has a code, a five digit Arabic numeral. So the first step was to match the actual numerical designation of the unit with the code, tally them, and then calculate out how many troops were involved in the Beijing martial law operation.++

“I was shocked with the number that came out: a total of 14 army groups. Among them were six army groups in the Beijing Military Zone: Nos. 24, 27, 28, 38, 63, 65. From the Jinan Military Zone there were four army groups: Nos. 20, 26, 54, and 67. From the Shenyang Military Zone there were three: Nos. 39, 40, and 64. The Nanjing Military Zone’s 12th Group Army also participated. At the time, the PLA ground forces had a total of 24 Group Armies. Other troops that were involved include the Tianjin Garrison Command’s 1st Tank Division, the Beijing Military Zone’s 14th Artillery Division, Beijing Garrison Command’s 1st and 3rd Guard Divisions, its 15th Airborne Corps, and the Beijing Armed Police unit (an army-level command). Altogether, there were 19 troops.++

“Of course, these groups didn’t take part in their entireties. Take for example the 38th Group Army — its total force sat at about 70,000 personnel. Based on a calculation of the size of all the units that actually entered Beijing, I calculated that it was roughly 200,000. I think it is pretty accurate.++

Chinese Soldiers who Have Spoken About the Tiananmen Square Massacre

Wu Renhua told China Change: “So far, only two out of the 200,000 have come out, using their true identity, and spoken about their experiences. One is Zhang Sijun, a soldier with the 54th Group Army and now a veteran living in his home province of Shandong. He has been detained several times and harassed for speaking online about 1989. According to my research his testimony isn’t that valuable, but morally, it’s significant. If a large number of them testify, we would know so much more about the massacre.++

[Source: Yaxue Cao, China Change, June 3, 2016 ++]

Wu Renhua told China Change: “So far, only two out of the 200,000 have come out, using their true identity, and spoken about their experiences. One is Zhang Sijun, a soldier with the 54th Group Army and now a veteran living in his home province of Shandong. He has been detained several times and harassed for speaking online about 1989. According to my research his testimony isn’t that valuable, but morally, it’s significant. If a large number of them testify, we would know so much more about the massacre.++

[Source: Yaxue Cao, China Change, June 3, 2016 ++]

“The other is Lieutenant Li Xiaoming, who headed a radio station of the Antiaircraft Artillery Regiment of the 116th Infantry Division of the 39th Group Army. He was what we call a “student-officer” who enlisted after graduating from college. Following his discharge, he went to study in Australia and became a Christian. He held a press conference and spoke about his experiences. It is from his testimony that we learned about another general who disobeyed orders, in addition to Xu Qinxian, the commander of the 38th Group Army.++

“That was Xu Feng, commander of the 116th Infantry Division of the 39th Group Army. I had done so much research, and I discovered the passive resistance on the part of General He Yanran, the commander of the 28th Group Army, and Zhang Mingchun, the political commissar, but I had known nothing about the division commander. Because of his refusal, he was disciplined and discharged after June 4. I have wanted to know his whereabouts and what happened to him, but I have never found any more about him despite my efforts.++

What about the commander and the political commissar of the 28th Group Army? They were both demoted and removed from the combat forces. Zhang Mingchun was demoted and reassigned to deputy political commissar of Jilin Provincial Military Command, and He Yanran the deputy commander of Anhui Provincial Military Command. Zhang Mingchun died a year after being demoted.++

Tiananmen Square Violence in Chengdu

A number of other cities were involved in protests. According to NPR: “The world media captured the 1989 protests and crackdown in Beijing's Tiananmen Square. But across China, similar protests were taking place. Students in the southwest city of Chengdu began their own hunger strike in Tianfu Square several days after their Beijing counterparts.

The final chapter of “The People’s Republic of Amnesia: Tiananmen Revisited”,Louisa Lim, recounts the crackdown on protesters in Chengdu. In her NPR report she wrote: “Protests in Chengdu mirrored those in Beijing's Tiananmen Square, with students mourning the sudden death from a heart attack of reformist party leader Hu Yaobang on April 15, 1989. This soon morphed into mass protests, followed by a hunger strike beginning in mid-May. Students occupied Chengdu's Tianfu Square, camping at the base of its 100-foot-tall Chairman Mao statue and proudly proclaiming it to be a "Little Tiananmen." The initial move by police to clear protesters from Tianfu Square on the morning of June 4 went ahead relatively peacefully. But on hearing the news that troops had opened fire on unarmed civilians in Beijing, the citizens of Chengdu took to the streets once more. This time they knew the risk; they carried banners denouncing the "June 4th massacre" and mourning wreaths with the message: "We Are Not Afraid To Die." [Source: Louisa Lim, NPR, April 15, 2014 ^-^]

“Soon the police moved in with tear gas. Pitched battles broke out in Tianfu Square. Protesters threw paving stones at the police; the police retaliated by beating protesters with batons. At a nearby medical clinic, the bloodied victims of police brutality lay in rows on the floor. Kim Nygaard, an American resident of Chengdu, recalled that they begged her: "Tell the world! Tell the world!" A row of patients sat on a bench, their cracked skulls swathed in bandages, their shirts stained scarlet near the collar, visceral evidence of the police strategy of targeting protesters' heads. But the violence went both ways: Dennis Rea, an American then teaching at a local university, watched, horrified, as the crowd viciously attacked a man they believed to be a policeman. The crowd pulled at his arms and legs, then dropped him on the ground and began stomping on his body and face, crushing it. ^-^

“Eight people were killed that day, including two students, according to the local government's official account. It said the fighting left 1,800 people injured — of them, it said, 1,100 were policemen — though it described most of the injuries as light. But U.S. diplomats at the time told The New York Times they believed as many as 100 seriously wounded people had been carried from the square that day. ^-^

“Protests continued into the next evening, and as June 5 turned into June 6, a crowd broke into one of the city's smartest hotels, the Jinjiang. It was there, under the gaze of foreign guests, that one of the most brutal — and largely forgotten — episodes of the Chengdu crackdown played out after a crowd attacked the hotel. More than a dozen Western guests initially took shelter in the quarters of the U.S. consul general. But in the early hours of the morning while returning to her room, Nygaard saw what looked like sandbags piled in the courtyard. As she wondered what they would be used for, she spotted a flicker of movement and realized with a chill of horror that the sandbags were actually people lying face-down on the ground, their hands secured behind their backs. "I remember so well, because I was thinking, 'Oh my God, they're breaking their arms when they're doing that,' " she told me. ^-^

“Eventually, two trucks pulled up. Nygaard remembers that moment vividly: "They piled bodies into the truck, and we were, like, 'There's no way you could survive that.' Certainly the people on the bottom would have suffocated. They picked them up like sandbags, and they threw them into the back of the truck. They threw them like garbage." Five separate witnesses described the same scene, which was also mentioned in a U.S. diplomatic cable. The witnesses estimated they had seen 30 to 100 bodies thrown into the trucks. The local government made no secret of the detentions. The Whole Story of the Chengdu Riots, a Chinese-language book recounting the official version of events, notes that "70 ruffians" had been caught at the Jinjiang hotel. As to what happened to those detainees and how many — if any — of them died, it is impossible to know. The Chengdu protests were immediately labeled "political turmoil" on a par with Beijing, with the protesters seen as "rioters," stigmatizing all who took part.” ^-^

The number of cities involved in protests was highlighted in an exhibition after the massacre in Beijing’s Military History Museum and cited by James Miles in The Legacy of Tiananmen: China in Disarray (University of Michigan Press, 1996).

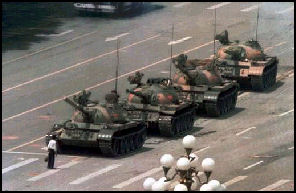

Tank Man of Tiananmen Square

The image identified most with the Tiananmen Square demonstrations is that of a white-shirted young man, with a shopping bag in each hand, who stood in front of a line of 17 tanks and refused to budge. His historic showdown was broadcast live around the world on C.N.N. The incident didn't take place at Tiananmen Square but rather east of the square on the Avenue of the Eternal Palace, just beyond the old Beijing Hotel.

The image identified most with the Tiananmen Square demonstrations is that of a white-shirted young man, with a shopping bag in each hand, who stood in front of a line of 17 tanks and refused to budge. His historic showdown was broadcast live around the world on C.N.N. The incident didn't take place at Tiananmen Square but rather east of the square on the Avenue of the Eternal Palace, just beyond the old Beijing Hotel.

Liao Yiwu wrote in The Nation: “The only protester people know about in the West is “Tank Man,” the guy in that iconic photograph who stood in the street, physically blocking the oncoming column of tanks billowing exhaust like gigantic farting beetles. They kept trying to make their way around him, but he kept getting in their way. You’re steel, and I’m flesh and blood, he seemed to be saying. Come get me if you dare! This moment was preserved for posterity because a foreign reporter happened to capture it on video. They say even Bush Sr. wept as he was watching the broadcast. But there were countless Tank Men whose deeds were not captured on camera.” [Source: “All You Want Is Money! All I Want Is Revolution!: Before the Tiananmen Square massacre, everyone loved China; now everyone loves the renminbi” by Liao Yiwu, The Nation, November 17, 2015]

The incident involving the Tank Man occurred around noon on June 5th, the day after the massacre. The man held his ground for about a minute or so. When the tank at the front of the line of tried to go around him he moved to the right and then to the left to block it. Then he shifted both shopping bags to one hand and jumped on the tank and appeared to say something to the driver. Finally a bystander stepped forward and pulled the man away to safety.

The young man has never been identified. His fate is unknown. His image though has appeared on posters and T-shirts but we only see him from the back. The Chinese government reportedly conducted a thorough search for him but turned up nothing.

Time magazine called him one of top 20 leaders and revolutionaries of the 20th century. A song about him appeared in a Wim Wenders film. John Kamm, the director of the Dui Hua Foundation a San-Francisco-based human rights group, told the Los Angeles Times, “For me he represents the unknown soldier of the Chinese democratic revolution. What’s so strange is that his act of bravery was conducted in plain view of the world. But other than seeing his act, we know very little about him.”

But as well known as he in the West few in China have seen him. No newspaper has shown his image. Attempts to pick up teh image on the Internet are blocked by government censors. Some of the few Chinese who have heard of him doubt whether he is even Chinese.

Photograph of the Tank Man

There are at least four versions of the famous Tank Man scene, each captured by a photographer shooting from the Beijing Hotel. The most famous photograph of the man and the tank was taken by Jeff Widener, then a 33-year-old Bangkok-based AP photographer. The day before the event, on June 4, he suffered a concussion after being hit in the face by a brick thrown by a protester and heard soldiers were using cattle prods to get photographers to turn over their film. On the day he shot the picture he asked a student he met if he could take photographs from the student’s room on the sixth floor of the Beijing Hotel, not far from Tiananmen Square. Out of film he borrowed a roll from the student and went to the room’s balcony

Using a device that doubled the power of his 400-millimeter telephoto lens, Widener watched the tanks rumble down the street almost a kilometers away. He later told Smithsonian magazine, “The protester walks out and I’m thinking, “This guy is going to screw up my [photograph]...That’s how messed up I was. I knew they were going to shot him, so I got focused and waited for them to shoot him. Then he started to walk up to the tank.” By the time he realized the f-stop was the wrong setting for the borrowed film he already snapped the pictures and the man had been pulled away by students. Widener then gave the film to the students who stuffed it in his underwear and bicycled to the AP office, After the grainy photograph was developed it put on the AP news wire. Others took similar photographs but Widener’s was the first to be widely circulated.

Liao Yiwu wrote in the NY Review of Books: “Tank Man was not one of the student leaders, he was no intellectual, nobody had ever heard of him. He left behind this short scene, an indelible historical icon, and then some people led him away by the arm. No one knows what became of him. Even the people in my book who were given heavy prison sentences—none of them ever heard about Tank Man in their jails and prison camps. Twenty-five years have gone by, we have all grown old. But Tank Man in these pictures is still so young. From far away, his white shirt looks like a lily in summer, pure and unblemished. Tanks stopping in front of a lily. A historical moment, a poetic moment. And on the other side of that moment, maybe three thousand lives were taken away, to be forgotten. [Source: Liao Yiwu, NY Review of Books, June 3, 2014, Translated by Martin Winter ***]

Chinese Government Position on Tiananmen Square

Five days after the massacre Deng accused the demonstrators of trying "to overthrow the Communist Party and demolish the socialist system" and praised the troops that crushed them. On June 19, Li Peng said, We can in no way leave [rioters] unpunished and let them stage a comeback."

Afterwards Deng said, “This has been a wake up call for all of us. In the future...we will use severe measures to stamp out the first signs of turmoil.” In a speech in 1990, Deng said, "If someone practices bourgeois human rights and democracy, we have to stop them." But at the same time he insisted that his program of economic liberalization would continue. China would not become a "closed country," he said, nor would it go "back to the old days of trampling the economy to death."

The Chinese government characterized Tiananmen Square demonstrations both as a "counterrevolutionary riot led by a bunch of hooligans" and a well-organized insurrection led by a few "Black Hands." Deng's daughter told New York Times that the fiasco was partly the result of China's inexperience in riot control. "It was a tragedy," she said. "No Chinese person wanted to see something happen like what happened then. Many people died, both among the ordinary people and among the military, and some of them died very cruel deaths."

Crackdown After Tiananmen Square

Washington Post bureau chief John Pomfret was kicked of China on charges of stealing state secrets and violating martial law provisions. On his own arrest Bao said he as driven to Zhongnanhai party headquarters and greeted there by a Politburo member who gave him an unusually strong handshake when they parted. When he left he found his car had been replaced by a police car. “I knew everything was over,” he told the Times. “I was being arrested. We drove for more than an hour and finally went through a large iron gate. Three men waited for me. I asked if I was at Qincheng prison,” the infamous jail where the Gang of Four and others were imprisoned. “They told me I would be known only as Prisoner 8901. Then I knew I was the first person arrested for the year. It was the start of the crackdown.”

Bao Tong, the most senior party official to be jailed after the demonstrations. He spent seven years in prison and was placed on house arrest after that. As of 2009, he was still being monitored by guards 24 hours a day. As of 2009, Bao Ting was still not allowed access to the Internet and couldn’t own a fax machine or even a reliable cell phone.

How Many Were Killed in the Tiananmen Square Massacre? 200 or 10,000

The question of how many people died during the Tiananmen Square massacre with a degree of accuracy is still unanswered. Estimates of the number of deaths generally range from several hundred to about 3,000. A Chinese government statement issued at the end of June 1989 said that 200 civilians and several dozen security personnel had died in Beijing following the suppression of "counter-revolutionary riots" on 4 June 1989.

Wu Renhua, author three books on Tiananmen Square told China Change: “I have no answer for this question. Unlike other people, I can’t just casually answer 2,000 or 3,000. This is the question that prompted me to write” a fourth book. “This book will be about the massacre and not limited to Tiananmen Square or Chang’an Avenue. Through this book, I will try to answer this crucial question of how many people died. The work of the Tiananmen Mothers for so many years has been to seek out and record information about the victims. They have a list of those who died in the massacre, and so far have recorded and verified the names of 202 victims. This is still quite far from the real death toll, but the work they’ve done has already been extremely difficult. [Source: Yaxue Cao, China Change, June 3, 2016 ++]

In 2017, the BBC reported: The Chinese army crackdown on the 1989 Tiananmen Square protests killed at least 10,000 people, according to newly released UK documents. The figure was given in a secret diplomatic cable from then British ambassador to China, Sir Alan Donald. The original source was a friend of a member of China's State Council, the envoy says. Sir Alan's telegram is from 5 June, and he says his source was someone who "was passing on information given him by a close friend who is currently a member of the State Council". The council is effectively China's ruling cabinet and is chaired by the premier. The cables are held at the UK National Archives in London and were declassified in October, when they were seen by the HK01 news site. [Source: BBC, December 23, 2017]

“Sir Alan said the source had been reliable in the past "and was careful to separate fact from speculation and rumour". The envoy wrote: "Students understood they were given one hour to leave square but after five minutes APCs attacked. "Students linked arms but were mown down including soldiers. APCs then ran over bodies time and time again to make 'pie' and remains collected by bulldozer. Remains incinerated and then hosed down drains. "Four wounded girl students begged for their lives but were bayoneted." Sir Alan added that "some members of the State Council considered that civil war is imminent".

Image Sources: AP, YouTube

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated August 2021