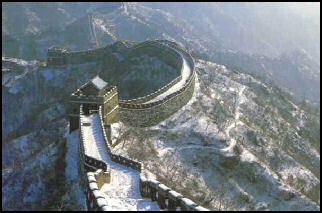

GREAT WALL OF CHINA

By some reckonings it is the largest structure ever built by humans. The Great Wall of China is the world's longest wall. Estimates of its length vary from 2,400 kilometers (1,500 miles) to 50,300 kilometers (31,250 miles), with most sources saying it is between 6,275 kilometers (3,900 miles) and 7,240 kilometers (4,500) miles long. According to the Guinness Book of Records, the main line's length is 3,460 kilometers (2,150 miles), with an additional 3530 kilometers (2,195 miles) of branches and spurs. According to the Chinese government, the Great Wall embraces a 3,460-kilometer (2,150-mile) -long main wall, occasionally broken up by mountains and other obstacles, and 2865 kilometers (1,780 miles) of spurs and additions. In 2012, the Chinese government said a careful reassessment determined the Great Wall is 21,198 kilometers (13,171 miles) long, [Sources: Peter Hessler, National Geographic, January 2003, The New Yorker, May 21, 2007; Los Angeles Times, July 2012]

By some reckonings it is the largest structure ever built by humans. The Great Wall of China is the world's longest wall. Estimates of its length vary from 2,400 kilometers (1,500 miles) to 50,300 kilometers (31,250 miles), with most sources saying it is between 6,275 kilometers (3,900 miles) and 7,240 kilometers (4,500) miles long. According to the Guinness Book of Records, the main line's length is 3,460 kilometers (2,150 miles), with an additional 3530 kilometers (2,195 miles) of branches and spurs. According to the Chinese government, the Great Wall embraces a 3,460-kilometer (2,150-mile) -long main wall, occasionally broken up by mountains and other obstacles, and 2865 kilometers (1,780 miles) of spurs and additions. In 2012, the Chinese government said a careful reassessment determined the Great Wall is 21,198 kilometers (13,171 miles) long, [Sources: Peter Hessler, National Geographic, January 2003, The New Yorker, May 21, 2007; Los Angeles Times, July 2012]

The oldest parts of the Great Wall date back to the 7th century B.C. For self-protection, rival kingdoms built walls around their territories, laying the foundation for the present Great Wall. When Emperor Qin Shihuang unified the whole country in 221 B.C., the existing walls were linked up and new ones added to counter attacks by the remnants of defeated states. Most of The Great Wall that we see today dates back to the Ming Dynasty (1368–1644).

Brook Larmer wrote in Smithsonian Magazine: “Few cultural landmarks symbolize the sweep of a nation's history more powerfully than the Great Wall of China. Constructed by a succession of imperial dynasties over 2,000 years, the network of barriers, towers and fortifications expanded over the centuries, defining and defending the outer limits of Chinese civilization. At the height of its importance during the Ming dynasty (1368-1644), the Great Wall is believed to have extended some 4,000 miles, the distance from New York to Milan. From its origins under the first emperor in the third century B.C., the Great Wall has never been a single barrier, as early Western accounts claimed. Rather, it was an overlapping maze of ramparts and towers that was unified only during frenzied Ming dynasty construction, beginning in the late 1300s. As a defense system, the wall ultimately failed, not because of intrinsic design flaws but because of the internal weaknesses—corruption, cowardice, infighting—of various imperial regimes.” [Source: Brook Larmer, Smithsonian Magazine, August 2008]

The Great Wall of China stretches across five northern Chinese provinces and five autonomous provinces from Bohai Bay on the Yellow Sea in the east to Jiayu Pass, 1,500 miles away, in the Gobi Desert, in the west. Ranging in height from five meters to 13 meters, and up to 10 meters thick, The Great Wall is longer than the the Nile River (six Great Walls could stretch around the entire earth) and contains an estimated 400 million cubic yards of material, enough to build 120 pyramids equal in size to the Great Pyramid of Cheops, and enough to build all the buildings in Scotland and England in 1793.

The Great Wall is probably China's greatest cultural icon. It comprises walls, passes, watchtowers, castles and fortresses. The walls are made of large stone blocks. The most comprehensive and technologically advanced survey to date — a two-year mapping project finished in 2009, using GPS and infrared technology — determined the wall stretches for 8,851.8 kilometers and includes 6,259.6 kilometers of actual wall, 359.7 kilometers of trenches and 2,322.5 kilometers of natural barriers such as mountains and rivers.

RELATED ARTICLES IN THIS WEBSITE: GREAT WALL OF CHINA TODAY: THREATS, PRESERVATION, MAPPING AND RESEARCH factsanddetails.com ; GREAT WALL OF CHINA NEAR BEIJING factsanddetails.com ; GRAND CANAL OF CHINA factsanddetails.com; WATER PROJECTS IN ANCIENT CHINA factsanddetails.com MEDIEVAL CHINESE WARFARE AND MILITARY TECHNOLOGY factsanddetails.com; SUN TZU AND THE ART OF WAR factsanddetails.com;

Good Websites and Sources on the Great Wall of China: Great Wall of China.com greatwall-of-china.com ; Wikipedia Wikipedia ; UNESCO World Heritage Site Sites UNESCO World Heritage Site

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: “The Great Wall Of China — Paperback – Picture Book” by Leonard Everett Fisher Amazon.com; “The Great Wall: China Against the World, 1000 BC–AD 2000" by Julia Lovell Amazon.com; "The Great Wall of China from History to Myth" Amazon.com; “The Great Wall of China" by Daniel Schwartz. Amazon.com; “The Grand Canal of China” by Howard Coats and Sun Zhen Amazon.com

Names and Claims and the Great Wall of China

Great Wall guard tower

The Chinese word for the Great Wall of China has traditionally been changcheng, which literally means “long wall” or “long walls.” When it was being built the walls were known by at least ten different names The Ming usually called them "bianquing" (“border walls”).

The term Great Wall was coined by Europeans and began to be widely used towards the end of the 19th century. Before that it was referred to by foreigners mostly as the “Chinese Wall.” Only in the 20th century after Westerners began calling it the Great Wall did the Chinese start calling it something similar: "Wanli Changcheng" (literally “10,000 li long wall”).

Many of the claims made about the Great Wall are untrue. It is not a single wall. It did not halt the Mongol invasion. And, it cannot be seen from the moon. "Although we can see things as small as airport runways," space shuttle astronaut Jay Apt wrote in National Geographic, "the Great Wall seems to made largely of materials that have the same color as the surrounding soil. Despite persistent stories that it can be seen from the moon, the Great Wall is almost invisible from only 180 miles up!"

According to a Scientific American report the Great Wall is visible only “from low orbit under a specific set of weather and lighting conditions.” Other man-made objects such as the pyramids are visible from space.

The source of the claim that the Great Wall can be seen from the moon is a 1925 National Geographic article which began. “According to astronomers, the only work of man’s hands which could be visible from the moon is the Great Wall of China.” Some also attribute the claim to a letter written in 1874 by English antiquarian William Stukely. In it he stated that Hadrian’s Wall is exceeded in length only "by the Chinese wall, which makes a considerable figure upon the terrestrial globe, and may discerned be at the moon.”

Great Wall: UNESCO World Heritage Site

The Great Wall was designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1987.According to UNESCO: “ ”In c. 220 B.C., under Qin Shi Huang, sections of earlier fortifications were joined together to form a united defence system against invasions from the north. Construction continued up to the Ming dynasty (1368–1644), when the Great Wall became the world's largest military structure. Its historic and strategic importance is matched only by its architectural significance...The Great Wall integrally preserves all the material and spiritual elements and historical and cultural information that carry its outstanding universal value. The complete route of the Great Wall over 20,000 kilometers, as well as elements constructed in different historical periods which constitute the complicated defence system of the property, including walls, fortresses, passes and beacon towers, have been preserved to the present day. The building methods of the Great Wall in different times and places have been integrally maintained, while the unparalleled national and cultural significance of the Great Wall to China is still recognised today.

“The Great Wall was continuously built from the 3rd century B.C. to the 17th century A.D. on the northern border of the country as the great military defence project of successive Chinese Empires, with a total length of more than 20,000 kilometers. The Great Wall begins in the east at Shanhaiguan in Hebei province and ends at Jiayuguan in Gansu province to the west. Its main body consists of walls, horse tracks, watch towers, and shelters on the wall, and includes fortresses and passes along the Wall.

The Great Wall reflects collision and exchanges between agricultural civilizations and nomadic civilizations in ancient China. It provides significant physical evidence of the far-sighted political strategic thinking and mighty military and national defence forces of central empires in ancient China, and is an outstanding example of the superb military architecture, technology and art of ancient China. It embodies unparalleled significance as the national symbol for safeguarding the security of the country and its people.

1) The Great Wall of the Ming is, not only because of the ambitious character of the undertaking but also the perfection of its construction, an absolute masterpiece. The only work built by human hands on this planet that can be seen from the moon, the Wall constitutes, on the vast scale of a continent, a perfect example of architecture integrated into the landscape. 2) During the Chunqiu period, the Chinese imposed their models of construction and organization of space in building the defence works along the northern frontier. The spread of Sinicism was accentuated by the population transfers necessitated by the Great Wall. 3) That the Great Wall bear exceptional testimony to the civilizations of ancient China is illustrated as much by the rammed-earth sections of fortifications dating from the Western Han that are conserved in the Gansu province as by the admirable and universally acclaimed masonry of the Ming period.

4) This complex and diachronic cultural property is an outstanding and unique example of a military architectural ensemble which served a single strategic purpose for 2000 years, but whose construction history illustrates successive advances in defence techniques and adaptation to changing political contexts. 5) The Great Wall has an incomparable symbolic significance in the history of China. Its purpose was to protect China from outside aggression, but also to preserve its culture from the customs of foreign barbarians. Because its construction implied suffering, it is one of the essential references in Chinese literature, being found in works like the "Soldier's Ballad" of Tch'en Lin (c. 200 A.D.) or the poems of Tu Fu (712-770) and the popular novels of the Ming period.

NASA radar image of the Great Wall

Composition of the Great Wall of China

The Great Wall is many different walls built at different times by different dynasties, composed of hundreds, if not thousands of disconnected sections. Most sections are composites of fortifications built by several dynasties, with most of the work done during the Ming dynasty. The Ming wall alone extends over 3,800 miles, with 6,700 beacon towers,

The Great Wall is made of packed earth, bricks and mortar, fieldstones and quarried rock. Some sections are made of stone and have crenelated watchtowers with vaulted ceilings and arched windows. Others are little more than crumbling piles of mud brick with animal shelters carved in them. In some places it isn’t a wall at all but a string of unconnected signal towers. Most sections are made of tamped earth. Long sections run across the tops of mountains and ridge tops, incorporating natural barriers such as cliffs and steep slopes. The Great Wall has outlived its usefulness for several centuries now and until fairly recently had been left to crumble into dust. Its only real use today is as a tourist attraction.

There are two main sections: the stone walls built as lines of defense around Beijing and the walls made mostly of tamped earth further to the west. The concept that the Great Wall is a continuous wall made of stone is derived largely by marrying the stone Ming walls that one sees north of Beijing, built between the 14th and 17th century, with descriptions of a 3.000 mile built in the 3rd century B.C. under Emperor Qin Shihuang.

Even today its is not clear what qualifies as a section of the Great Wall and what doesn’t. Some say that a section has to be a part of a 100 kilometer long chain to qualify. Other say any border fortification can be included. A satellite survey determined there were 390 miles of walls just in the Beijing area. Field work has determined that there is much more than that.

Much of the land around the wall is deforested . One reason for this is that the Imperial government decreed that all grass and trees within 100 kilometers of the wall be cleared to deprive attacking enemies of opportunities for surprise attacks. Near the wall the land was used to raise crops to feed soldiers that were stationed at the walls.

Walls in China

The word for city in Chinese is the equivalent of “walled city.” Arthur Henderson Smith wrote in “Chinese Characteristics”: The laws of the Empire require that every district city, as well as every city of a higher rank, shall be enclosed by a wall of a specified height. Like other laws, this statute is much neglected in the letter, for there are many cities the walls of which are allowed to crumble into such decay, that they are no protection whatever, and we know of one district city invested by the Taiping rebels and occupied by them for many months, the walls of which although utterly destroyed were not restored at all for more than a decade afterwards. Many cities have only a feeble mud rampart, quite inadequate to keep out even the native dogs, which climb over it at will. But in all these cases, the occasion of these lapses from the ideal state of things is simply the poverty of the country. Whenever there is an alarm of trouble, the first step is to repair the walls. The execution of such repairs affords a convenient way in which to fine officials or others who have made themselves too rich in too short a time. [Source:“Chinese Characteristics” by Arthur Henderson Smith, 1894]

“The firm foundation on which rest all the many city walls in China, is the distrust which the Government entertains of the people. However the Emperor may be in theory the father of his people, and his subordinates called "father and mother officials," all parties understand perfectly that these are purely technical terms, ie. plus and minus, and that the real relation between the people and their rulers is that between children and a step-father. The whole history of China appears to be dotted with rebellions, most of which might apparently have been prevented by proper action on the part of the general Government if taken in time. The Government does not expect to act in time. Perhaps it does not wish to do so, or perhaps it is prevented from doing so. Meantime, the people slowly rise as the Government knew they would, and the officials promptly retire within these ready-made fortifications, like a turtle within its shell, or a hedge-hog within its ball of quills, and the disturbance is left to the slow adjustment of the troops."

“The lofty walls which enclose all premises in Chinese, as in other Oriental cities and towns, are another exemplification of the same traits of suspicion. If it is embarrassing for a foreigner to know how to speak to a Chinese of such places as London or New York, without unintentionally conveying the notion that they are " waited cities," it is not less difficult to make Chinese who may be interested in Western lands, understand how it can be that in those countries people often have about their premises no enclosures whatever. The immediate, although unwarranted inference on the part of the Chinese is that in such countries there must be no bad characters of any kind.

Even in cases of local disturbance, when there appears to the Chinese to be no safety except such as may be got by the protection of earthen walls thrown up around villages, and when the danger, being most imminent, requires instant action, it is sometimes difficult to secure sufficient unanimity to make a wall possible. In one such case near to the writer's home, a large village disagreed, and actually separated into two sections, throwing up two distinct circumvallations, one for each end of the town, to the mutual inconvenience of each, and at a great additional expense.

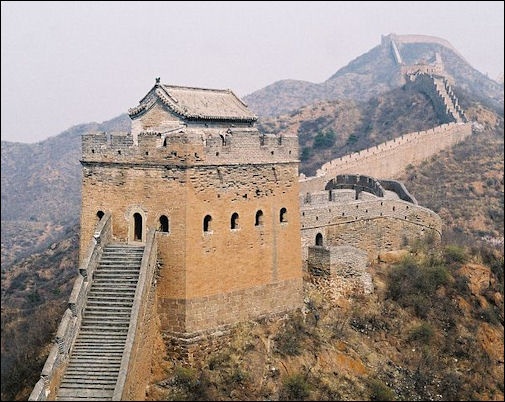

Great Wall of China Watchtowers

The first watchtowers were built in the mid 1500s near Dongjiakou village, in eastern Hebei Province, about 270 kilometers from Beijing, by Ming soldiers under the command of General Qi Jiguang. They were added to an earlier stone and earthen barrier, erected nearly two centuries before at the beginning of the Ming dynasty. The watchtowers were built at at every peak, trough and turn between 1569 and 1573. [Source: Brook Larmer, Smithsonian Magazine, August 2008]

On the Great Wall watchtowers, Brook Larmer wrote in Smithsonian Magazine: “They enabled troops to shelter in secure outposts on the wall itself as they awaited Mongol attacks. Even more vitally, the towers also functioned as sophisticated signaling stations, enabling the Ming army to mitigate the wall's most impressive, but daunting, feature: its staggering length. Relying on observation sites like this one, soldiers transmitted signals from the front lines back to the military command. Employing smoke by day and fire at night, they could send messages down the line at a rate of 620 miles per day—or about 26 miles per hour, faster than a man on horseback. According to Cheng Dalin, a leading authority on the wall, the signals also conveyed the degree of threat: an incursion of 100 men required one lighted beacon and a round of cannon fire, he says, while 5,000 men merited five plumes of smoke and five cannon shots. The tallest, straightest columns of smoke were produced by wolf dung, which explains why, even today, the outbreak of war is described in literary Chinese as "a rash of wolf smoke across the land."

Military Importance of the Great Wall of China

Great Wall tower

In his book "The Great Wall of China", the Sinologist Arthur Waldron, the the Wall was one of three defensive strategies that successive dynasties used to deal with Manchurians. Mongolians and other northern barbarians: 1. Intermarriage and diplomacy; 2. Scorched earth military campaigns into the barbarians own territory; and 3. Defensive wall building. Waldron suggests that the third strategy was the weakest, and that it was only in the more paranoid later Ming Dynasty that the strategy really took hold. Alastair Johnston and Julia Lovell promote the same reasoning. [Source: Posted by Jeremy Goldkorn, Danwei.org, October 6, 2009]

On the military importance of the Great Wall, Spindler told Danwei.org, “ First, there are several important examples of the Chinese using the Great Wall to fend off raids of several thousand Mongols, mostly in the third quarter of the sixteenth century. There are many more examples of the Chinese successfully using the Great Wall to defend against smaller raids in a much longer span of time.” [Ibid]

“Where I depart from Waldron is that he sees individual officials as advocating one of these strategies to the exclusion of the others and wall-building as a compromise policy when advocates of the first two cannot agree.” Spindler said. “All three of these strategies coexisted throughout nearly the entire Ming dynasty and were simply applied in different mixtures, at different times and in different places. There was no such thing as an advocate of wall-building at the exclusion of all other strategies, or someone who believed that diplomacy or pre-emptive strikes were the only way to make China strong on its northern border. In my opinion, wall-building wasn’t a compromise policy but an important strategy in its own right.” [Ibid]

Uses of the Great Wall of China

Fortifications and walls were solidified into the Great Wall of China to keep invaders from the north out. But keeping the barbarians out of China was not the only reason for the wall. It was also built for land grabbing purposes. According to historian Julia Lovell, author of a book about the Great Wall, it extended “hundreds of kilometers from the farmable land” in order to “police people” and “control lucrative trade routes.”

At one time more than 40,000 watchtowers were strung along the Great Wall. Messages were relayed using signals made from fire, smoke, and gunpowder.

Smoke was used in the day and fire at night. Messages could be sent at a rate of 620 miles a day— about 26 miles an hour, faster than a man can ride on horseback. The most important messages were information of impending attacks with one lighted beacon and one round of cannon fire conveying an incursion of 100 men and five plumes of smoke and five rounds of cannon fire signifying 5,000 men. The straightest and longest-lasting plumes of smoke were produced by wolf dung which is why even today an outbreak of war is described as “wolf smoke across the land.”

The Chinese also used the wall as an elevated highway to move troops and equipment through rugged terrain. Some sections of the wall are wide enough to accommodate five horsemen or 12 armed soldiers walking abreast. Emperors sometimes led entire armies along the top of the wall.

Many people live near the wall and continue to use it today. Some have their houses built into it. One family with a house with 20-foot-thick walls told National Geographic it is “very warm in the winter, cool in the summer.” Some villages are entirely enclosed in high-walled forts and have the characters for “fort,” “barracks” or “checkpoint” in their name. In other places holes have been pinched in the wall to allow sheep to pass and stones have been cannibalized as construction material and even sold to tourists at a price of $10 for one 10 kilogram stone.

Early History of the Great Wall of China

Early Great Wall

The first sections of the Great Wall were built between 770 and 450 B.C. by small independent, often warring, kingdoms. It was first thought that the fortifications were built by small Chinese kingdoms to protect their irrigated lands along the Yangtze and Yellow rivers from steppe nomads to the north because the first walls were built roughly on a line originally thought to separate the fertile river valleys of the south from the steppe to the north. This was not always true, however. Sections of wall rose and fell with provincial states and were defined by a number of factors. The sections in present-day Hebei and Liaoning Prefectures are said to be the oldest.

Beginning in 221 B.C., existing walls were linked together and reinforced under orders from Emperor Qin, the first emperor of unified China. Hundreds of thousands of workers took part in the project and perhaps tens of thousands of them died. Many were political prisoners who were sentenced to ten years of hard labor. The wall itself was made mostly from compacted earth. The 180 million cubic meters of material used now lies at core of many sections of the wall.

As invaders from the north became stronger the fortifications of the Great Wall of China were built up to keep them out. If the Great Wall was breached, the Chinese believed, the invaders would assimilate themselves into the Chinese way of life once they realized its "superior attractions." For over a thousand years this strategy worked. After a period of disruption, invaders usually married Chinese women and were in fact absorbed. The dynasties that ruled China for the most part took over after power struggles within the empire.

The main threat in the early years of the Great Wall came from the Hu, a horse-riding nomadic people from Central Asia. They were mentioned in records relating to the Warring States period (303-221 B.C.) and the Qin dynasty (221-207 B.C.). The Hu had no interest in assimilation and easily skirted the wall.

Subsequent dynasties continued to rebuild and restore the walls, and occasionally criminals and political prisoners were thrown threw the gates and left to survive on their own in the north. During the Han dynasty so many trees were felled for scaffolding an ecological disaster occurred. The Tang dynasty kept the barbarians at bay by encouraging trade and cultural exchanges rather than building walls. In the 13th century, the walls failed to stop Genghis Khan, who reportedly said, "the strength of the wall depends on the courage of those who defend it." He reportedly breached it by bribing a sentry.

Edward Wong wrote in the New York Times, “Beginning with the Qin dynasty, successive empires built different series of walled fortifications in the area now known as northern China. For example, the Han dynasty, which ruled China from 206 B.C. to 220 A.D., built walls and watchtowers along the Hexi Corridor, a passage between mountains and high plateaus leading through the Gobi Desert in western China. Remnants of the Han-era Great Wall can be found west of the former oasis town of Dunhuang and were explored in the early 20th century by Sir Aurel Stein, the British archaeologist. [Source: Edward Wong, Sinosphere, New York Times, June 29, 2015]

Great Wall of China Under the Ming Dynasty

The most famous and impressive sections of the Great Wall were built from mud, brick and stone during the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644). The Ming emperors devoted a huge amount of resources and manpower to the project. Stones weighing over a ton were shaped, moved and heaved on top of each other. Over 60 million tons of bricks and stone slabs were used.

The Ming built their walls as lines of defense with as many as four rows of fortifications in strategic areas. They used durable materials and construction methods, intending to make something that lasted. Stone was quarried in the Beijing area. The mud bricks were made of soil, straw, tamarisk, egg yolk and rice paste. The earth was tamped with large chunks of rock and special tools.

The project took over a 100 years to complete. At one time, nearly one in every three males in China was conscripted to help build it. Towns along the wall became industrial areas for firing bricks, blasting rocks to make fill and sharpening stones. Army units were put to work on a rotating basis so no one unit would be overworked and rebel.

The towers and walls were often made separately with the towers being made first from brick that was carried in. Wall sections were built between the towers, first with local stone, and later with materials that were carried in. Construction was usually done in the spring when the weather was good but the Mongols were not active (they usually raided and attacked in the fall after their horses had been fattened up on summer grass). In some places tablets identify when a given wall section was built and name the officials involved in building it.

Hundreds of thousand of people died from severe weather, starvation and exhaustion while building the Great Wall of China. Many women were widowed and children left without fathers. A popular Ming era song went: "If a son is born, mind you don't raise him! If a girl is born, don’t feed her dried meat. Don't you just see below the Long Wall, dead men's skeletons prop each other up.”

Many people who live around the Great Wall today, especially in the hills northeast of Beijing, claim to be descendants of soldiers that were stationed on the wall. Many of these trace their roots back to a policy in the mid 1550s that aimed to prevent soldiers firm deserting by allowing their wives and families to move into the watchtowers with them. Some of the towers bear the same surnames of the families that live in nearby villages.

In the 1500s, Ming General Qi Jiguang, trying to stem massive desertions, allowed soldiers to bring wives and children to the frontlines. Local commanders were assigned to different towers, which their families treated with proprietary pride. Today, the six towers along the ridge above Dongjiakou bear surnames shared by nearly all the village's 122 families: Sun, Chen, Geng, Li, Zhao and Zhang. [Source: Brook Larmer, Smithsonian Magazine, August 2008]

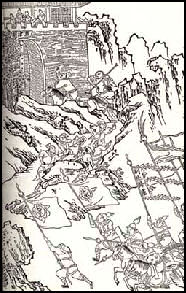

Great Wall of China Under Attack

While many scholars say that the Great Wall was no better than the Maginot line which failed to stop the Nazis from entering France, others say it served its purpose well. In the early years of the Ming dynasty the Chinese military often went on the offensive and pushed Mongol settlements away from the walls. Later the Chinese bribed Mongol leaders or set up lucrative trade opportunities to keep them from attacking. Many sections of the wall were built in the late Ming era when the Ming army was too weak to fight and the emperors were too proud to negotiate.

While many scholars say that the Great Wall was no better than the Maginot line which failed to stop the Nazis from entering France, others say it served its purpose well. In the early years of the Ming dynasty the Chinese military often went on the offensive and pushed Mongol settlements away from the walls. Later the Chinese bribed Mongol leaders or set up lucrative trade opportunities to keep them from attacking. Many sections of the wall were built in the late Ming era when the Ming army was too weak to fight and the emperors were too proud to negotiate.

In a typical defense the Chinese used crude cannons, arrows cudgels and stones to defend against Mongol attacks. There were regulations about how many stones could used in a defense and how they would be carried to the wall. In some sections you can still see piles of stones ready to be used in the next attack.

The Mongols liked to approach the walls at night on horseback, in small groups. They followed ridge lines because they were concerned about ambushes. They were not interested in occupying land. They were raiders, who penetrated into Chinese territory and returned as quickly as possible. Often their objective was to steal livestock, valuables and Chinese people, who were forced into families, with the men trained to be spies behind Chinese lines while their wives and children stayed in Mongolia as hostages.

A major attack occurred in 1550 when the Mongols breached a crude section of stone wall and pillaged for two weeks, killing and capturing thousands of Chinese. After that more sturdy walls made with mortar were built. During the attack by Mongols around Jinshanling in October 1554, one document reported, a battle raged for two hours between 11:00am and 1:00pm. The Mongols used ropes to climb the walls. Chinese repelled them using arrows, crude cannons, clubs and even rocks. One Chinese soldier hacked off the hand of an attacker only to be killed moments later by an enemy arrow that pierced his head.

In 1576 there was another major Mongol attack. This time they penetrated through an area so rugged and remote building a wall was not considered necessary. During this raid the Mongols killed an estimated 20,000 Chinese. Another major campaign of wall building followed. After that the Chinese for the most were able to hold back the Mongols. At Shuitou, the Chinese withstood an attack by thousands of Mongols.

The invading Tatars broke through the Great Wall in 1550 and the Manchus poured through uncontested in 1644. Only about a third of the Ming Dynasty wall remains intact. Because of the high quality of the construction, some wall sections today look pretty much as it did in the Ming Dynasty.

Later History of the Great Wall of China

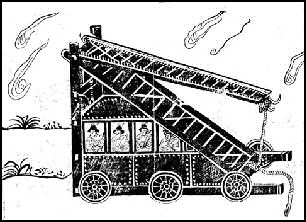

Cloud ladder, a Chinese

wall-mounting devise

After the Ming dynasty collapsed, Chinese intellectuals tended to see the Great Wall as huge waste of money and live. The Qing Dynasty let the walls deteriorate, in part because they were Manchu horsemen which the walls had been designed to keep out, plus they controlled territory far north of the wall. Into the 20th century the Great Wall was held in relatively low regard and was only given a boost when China needed a dose of nationalism to raise its esteem during bad times. Both Sun Yat-sen and Mao Zedong used the wall as symbols of Chinese strength, pride, hard work and greatness.

The Great Wall deteriorated under Mao. Peasants took tamped earth to patch their fields and grabbed stones to to build houses. In some places caves were dug into the wall to live in and store stuff. In other places stones were pried off by scorpion hunters looking for their prey. When asked what happened to missing sections many villagers will tell you they were dismantled to keep the Japanese from using them as observation posts and machine gun nests. During the Cultural Revolution in the early 1970s large parts of the wall were torn down by crowds chanting, "Down with the Four Olds" to make barracks and houses.

After the Cultural Revolution ended some sections were reportedly rebuilt by the same people who tore them down. A Deng Xiaoping era slogan went: "Let us love our China and restore our Great Wall!" In recent years the Great Wall has become quite popular. There are Great Wall tires, Great Wall wine, Great Wall cigarettes, Great Wall rockets and Great Wall computers.

More than 6,200 kilometers of the Ming-era wall’s 8,851.8 kilometers is artificial, and the rest consist of natural barriers according to Chinese sources. Edward Wong wrote in the New York Times, “The Ming dynasty Great Wall also stretched into Gansu and ended at a desert site called Jiayuguan, east of the surviving Han sections. It is the parts of the wall built during the Ming, which ruled China from 1368 to 1644, that are the best preserved. In Beijing, most tourists go to see the Ming wall at the renovated sections at Badaling or Mutianyu. In November 2009, President Obama walked along a temporarily closed-off section of Badaling, which is usually mobbed with tourists.” In March 2014 “his wife, Michelle Obama, went to Mutianyu with their two daughters and, to descend, took a ride in a plastic sled down a popular tourist slide. [Source: Edward Wong, Sinosphere, New York Times, June 29, 2015]

Tax Systems Used to Pay for Large-Scale Public Works in Ancient China

According to the “Treatise on Food and Money”: “There were two kinds of tax: the military levy and the production tax. The production tax concerned the one-tenth of total family grain production which was the product of its share of the public field, and also taxes on the crafted goods sold by artisans, merchant profits, and any fishing or forestry incomes of lands managed by wardens. The military levy was used to supply the armies with carts and carriages, horses, armor, and arms, as well as including quotas for infantry service. These taxes fully provided for the expenses of the state treasury and 7 arsenals, and for the gifts and grants that were bestowed by the state. The production tax was used to provide for the sacrifices to heaven and to earth, for the royal clan sacrifices, and for service to all the many spirits. It supplied the needs of the household of the Son of Heaven, for the salaries and sustenance of the state officials, and for miscellaneous state expenses. [Source: Han shu 24a.1118-23,“Treatise on Food and Money” by Ban Gu, 1st century A.D.]

Dr. Robert Eno of Indiana University wrote: This “tax regulation of 594 B.C. is widely discussed in various texts as a symptom of social decline. According to the traditional view, prior to this act, production taxes for the farming population were covered by the labor contributed to the public field (the well-field system). This may have been the case, or, if the well-field system did not, in fact, exist, the record may indicate a shift from taxing a harvest output to taxing land owned. This would have been an advantage to patrimonial estate holders as their incomes would have been guaranteed (at great cost to the security of the farming population). It may also indicate a shift in the concept of land ownership, regarding the peasants like land owners, rather than as serf-like subjects settled on the lord’s land. [Source: Robert Eno, Indiana University indiana.edu /+/ ]

“This new method of taxation levied on acreage may be linked to the rise of large-scale public works, such as the building of dams, canals, and state walls (the greatest of these ultimately being linked as the Great Wall of China). During the centuries of the late Spring and Autumn and early Warring States periods, iron technology was first applied to agriculture; along with new developments in irrigation and planting techniques, this greatly increased productivity. Under these conditions, estate holders would have found that the principal traditional form of tax, labor due on patrician fields, was not so efficient as a tax on personal crop yields plus labor time, directed no longer to the lord’s crops, but instead to public works. The economic and military benefits of these works became increasingly critical during the Warring States period, when competition among states drove governments towards increased size, aggressiveness, and public control.

Great Wall at Jinshangling

Were Parts of the Great Wall of China Used to Fence in Livestock?

James Rothwell wrote in The Telegraph: “It was supposedly built to keep the bloodthirsty Mongolian conqueror Genghis Khan at bay. But the northern segment of the Great Wall of China served a more mundane purpose, according to Israeli archaeologists who say it was actually used to hem in livestock. The archaeologists came to the conclusion, which challenges previous assumptions, after mapping out the Great Wall's 460-mile Northern Line for the first time. "Prior to our research, most people thought the wall's purpose was to stop Genghis Khan's army," said Prof Gideon Shelach-Lavi, an expert at Jerusalem's Hebrew University and the leader of the two year-study. [Source: James Rothwell, The Telegraph June 9, 2020]

“But the Northern Line, which lies mostly in Mongolia, winds through valleys, is relatively low in height and close to paths — which suggests it served non-military functions. "Our conclusion is that it was more about monitoring or blocking the movement of people and livestock, maybe to tax them," Prof Shelach-Lavi said. He suggested that people may have been seeking warmer southern pastures during a medieval cold spell.

“The Northern Line, also known as "Genghis Khan's Wall" in reference to the Mongolian conqueror, was built between the 11th and 13th centuries with pounded earth and dotted with 72 structures in small clusters. Prof Shelach-Lavi and his team of Israeli, Mongolian and American researchers used drones, high-resolution satellite images and traditional archaeological tools to map out the wall and find artefacts that helped pin down dates.According to Prof Shelach-Lavi, whose findings from the ongoing study were published in the journal Antiquity, the Northern Line has been largely overlooked by contemporary scientists.

Image Sources: 1) Great Wall, Nolls China website; 2) NASA; 3) Great Wall tower, Nolls China website http://www.paulnoll.com/China/index.html ; 4) Early Great Wall, Ohio State University; 5) Wall attack, University of Washington; 6) Wall-mounting ladder, University of Washington; Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated August 2021