GREAT WALL OF CHINA TODAY

Great Wall map Brook Larmer wrote in Smithsonian Magazine: “For three centuries after the Ming dynasty collapsed, Chinese intellectuals tended to view the wall as a colossal waste of lives and resources that testified less to the nation's strength than to a crippling sense of insecurity. In the 1960s, Mao Zedong's Red Guards carried this disdain to revolutionary excess, destroying sections of an ancient monument perceived as a feudal relic.” [Source: Brook Larmer, Smithsonian Magazine, August 2008 ]

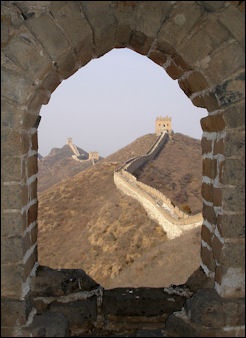

“Nevertheless, the Great Wall has endured as a symbol of national identity, sustained in no small part by successive waves of foreigners who have celebrated its splendors—and perpetuated its myths. Among the most persistent fallacies is that it is the only man-made structure visible from space. (In fact, one can make out a number of other landmarks, including the pyramids. The wall, according to a recent Scientific American report, is visible only "from low orbit under a specific set of weather and lighting conditions.") Mao's reformist successor, Deng Xiaoping, understood the wall's iconic value. "Love China, Restore the Great Wall," he declared in 1984, initiating a repair and reconstruction campaign along the wall north of Beijing. Perhaps Deng sensed that the nation he hoped to build into a superpower needed to reclaim the legacy of a China whose ingenuity had built one of the world's greatest wonders.”

Most of the sections visited by tourists were built in the Ming Dynasty and have been restored in the 20th century. Entire army units have been put to work rebuilding sections. Kilns have been set up to bake bricks. Rock faces have been dynamited to produce material for fill. Many sections have been rebuilt using ancient techniques and mortar according to ancient recipes. Laborers that do the rebuilding are paid about $3 a day.

More than 6,200 kilometers of the Ming-era wall’s 8,851.8 kilometers is artificial, and the rest consist of natural barriers according to Chinese sources. Edward Wong wrote in the New York Times, “The Ming dynasty Great Wall also stretched into Gansu and ended at a desert site called Jiayuguan, east of the surviving Han sections. It is the parts of the wall built during the Ming, which ruled China from 1368 to 1644, that are the best preserved. In Beijing, most tourists go to see the Ming wall at the renovated sections at Badaling or Mutianyu. In November 2009, President Obama walked along a temporarily closed-off section of Badaling, which is usually mobbed with tourists.” In March 2014 “his wife, Michelle Obama, went to Mutianyu with their two daughters and, to descend, took a ride in a plastic sled down a popular tourist slide. [Source: Edward Wong, Sinosphere, New York Times, June 29, 2015]

RELATED ARTICLES IN THIS WEBSITE: GREAT WALL OF CHINA factsanddetails.com ; GREAT WALL OF CHINA NEAR BEIJING factsanddetails.com ; WATER PROJECTS IN ANCIENT CHINA factsanddetails.com; MEDIEVAL CHINESE WARFARE AND MILITARY TECHNOLOGY factsanddetails.com; SUN TZU AND THE ART OF WAR factsanddetails.com

Good Websites and Sources on the Great Wall of China: Great Wall of China.com greatwall-of-china.com ; Wikipedia Wikipedia ; UNESCO World Heritage Site Sites UNESCO World Heritage Site

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: “The Great Wall Of China — Paperback – Picture Book” by Leonard Everett Fisher Amazon.com; “The Great Wall: China Against the World, 1000 BC–AD 2000" by Julia Lovell Amazon.com; "The Great Wall of China from History to Myth" Amazon.com; “The Great Wall of China" by Daniel Schwartz. Amazon.com; “The Grand Canal of China” by Howard Coats and Sun Zhen Amazon.com

Great Wall of China Under Threat

Soldiers marching on the Great Wall in the 1930s

Although large sections of the Great Wall have been restored for tourism, much of it is has collapsed, been claimed by weather or been carted off as building materials for peasant huts, pigpens, roads, buildings and reservoirs. There have been sections deliberately blasted to make way for highways and quarries. Some sections have been fouled with graffiti or Communist party slogans. Other sections have been developed and fixed up for tourists in nightmarish ways. By one estimate two thirds of the wall has been damaged or destroyed and the rest is threatened. By another estimate 20 percent of the wall has been restored, 40 percent is in ruins and 40 percent had disappeared.

Brook Larmer wrote in Smithsonian Magazine: “Today, China's most iconic monument is under assault by both man and nature. No one knows just how much of the wall has already been lost. Chinese experts estimate that more than two-thirds may have been damaged or destroyed, while the rest remains under siege...Today's threats come from reckless tourists, opportunistic developers, an indifferent public and the ravages of nature. Taken together, these forces—largely byproducts of China's economic boom—imperil the wall, from its tamped-earth ramparts in the western deserts to its majestic stone fortifications spanning the forested hills north of Beijing, near Badaling, where several million tourists converge each year.” [Source: Brook Larmer, Smithsonian Magazine, August 2008 ]

The western section of the wall has been worn away by wind, sand and water. Fierce winds blow off of the tops and sandblast the sides of the walls. Flash floods wash away the bases of the walls, causing the walls to weaken and collapse. Some sections have been covered desert sand dunes or have collapsed due to the continuous freezing and thawing of the wall's foundations. The mud sections have largely disintegrated.

The modern world has caught up with some sections of the Great Wall. One seven-mile section in Gansu that was unbroken when it was photographed by the archeologist Aurel Stein in 1910 is now crossed, according to Great Wall expert William Lindesay, by “two rail lines, 17 power lines, the west-to-east gas line, 15 dirt roads, one main road, an abandoned main road and the G-312 expressway which is actually routed under the Wall.”

Loss of Great Wall, Brick by Brick

Japanese fighting at the Great Wall in 1933

According to an article published in The Beijing Times in June 2015 that cites local officials, statistics and a Great Wall scholar, 22 percent of Great Wall has disappeared and the total length of the parts of the wall that have vanished, 1,961 kilometers, or 1,219 miles, is equal to about 30 percent of the artificial part of the Great Wall. Edward Wong wrote in the New York Times, “Those numbers were released in 2012 by the State Administration of Cultural Heritage, and no doubt more of the wall has disappeared since then...Outside Badaling, Mutianyu and a handful of other heavily visited sections, there is the “wild wall,” and it is in these areas — the vast majority of the Ming-era wall — that the structure is vanishing. [Source: Edward Wong, Sinosphere, New York Times, June 29, 2015 ==]

“The Beijing Times article caused a stir on social media. People’s Daily, the Communist Party’s flagship newspaper, wrote in English on Twitter: “Report on vanishing Great Wall shocks the country.” Global Times, a newspaper overseen by People’s Daily, expressed anxiety in a Twitter post: “Nearly 30 percent of Great Wall disappears. Fancy a trip before it’s all gone?” People’s Daily Online and Global Times both ran stories on Monday that repeated the findings of The Beijing Times. ==

“The Beijing Times reported that the main causes were erosion from wind and rain, the plundering of bricks by nearby villagers to use in construction and the scrambling over parts of the wild wall by more adventurous tourists. Some of the bricks taken by villagers have Chinese words carved into them. Scholars judge those bricks to be invaluable historical relics, yet the same bricks can be found sold in village markets near the Great Wall for about 40 to 50 renminbi, or about $7 to $8 — and that can be bargained down to 30 renminbi, according to The Beijing Times. ==

“In 2006, China established regulations for the protection of the Great Wall. But The Beijing Times said that with little in the way of resources devoted to preservation, and given the fact that the Ming-era wall runs through some impoverished counties, the regulations amount to “a mere scrap of paper.” Some Chinese citizens expressed concern online after seeing the Beijing Times report. “The modern Chinese have done what people for centuries were embarrassed to do and what the invaders could not do,” one person wrote on a Sina Weibo microblog. “The wall is being destroyed by the hands of the descendants.” ==

Great Wall of China Threatened by Desertification

Larmer wrote” “Nowhere are threats to the wall more evident than in Ningxia. The most relentless enemy is desertification—a scourge that began with construction of the Great Wall itself. Imperial policy decreed that grass and trees be torched within 60 miles of the wall, depriving enemies of the element of surprise. Inside the wall, the cleared land was used for crops to sustain soldiers. By the middle of the Ming dynasty, 2.8 million acres of forest had been converted to farmland. The result? "An environmental disaster," says Cheng. [Source: Brook Larmer, Smithsonian Magazine, August 2008]

“Today, with the added pressures of global warming, overgrazing and unwise agricultural policies, China's northern desert is expanding at an alarming rate, devouring approximately one million acres of grassland annually. The Great Wall stands in its path. Shifting sands may occasionally expose a long-buried section—as happened in Ningxia in 2002—but for the most part, they do far more harm than good. Rising dunes swallow entire stretches of wall; fierce desert winds shear off its top and sides like a sandblaster. Here, along the flanks of the Helan Mountains, water, ironically enough, is the greatest threat. Flash floods run off denuded highlands, gouging out the wall's base and causing upper levels to teeter and collapse.

Sandstorms in northwest China are blamed for reducing sections of the Great Wall of China to dust and dirt in remarkably short periods of time. The problem is particularly severe in Gansu Province where many sections are made of from mud and mud brick rather than brick and stone. One three mile section in Minqiin County in Gansu that was built in the Han Dynasty (206 B.C. to A.D. 220) is “rapidly disappearing” and may be gone in 20 years.

Construction and Pilfering Materials from the Great Wall of China

Brook Larmer wrote in Smithsonian Magazine: “ At Sanguankou Pass, two large gaps have been blasted through the wall, one for a highway linking Ningxia to Inner Mongolia—the wall here marks the border—and the other for a quarry operated by a state-owned gravel company. Trucks rumble through the breach every few minutes, picking up loads of rock destined to pave Ningxia's roads. Less than a mile away, wild horses lope along the wall, while Ding's sheep forage for roots on rocky hills. [Source: Brook Larmer, Smithsonian Magazine, August 2008 ]

“The plundering of the Great Wall, once fed by poverty, is now fueled by progress. In the early days of the People's Republic, in the 1950s, peasants pilfered tamped earth from the ramparts to replenish their fields, and stones to build houses. (I recently visited families in the Ningxia town of Yanchi who still live in caves dug out of the wall during the Cultural Revolution of 1966-76.) Two decades of economic growth have turned small-scale damage into major destruction. In Shizuishan, a heavily polluted industrial city along the Yellow River in northern Ningxia, the wall has collapsed because of erosion—even as the Great Wall Industrial Park thrives next door. Elsewhere in Ningxia, construction of a paper mill in Zhongwei and a petrochemical factory in Yanchi has destroyed sections of the wall.

“Regulations enacted in late 2006—focusing on protecting the Great Wall in its entirety—were intended to curb such abuses. Damaging the wall is now a criminal offense. Anyone caught bulldozing sections or conducting all-night raves on its ramparts—two of many indignities the wall has suffered—now faces fines. The laws, however, contain no provisions for extra personnel or funds. According to Dong Yaohui, president of the China Great Wall Society, "The problem is not lack of laws, but failure to put them into practice."

“Enforcement is especially difficult in Ningxia, where a vast, 900-mile-long network of walls is overseen by a cultural heritage bureau with only three employees. On a recent visit to the region, Cheng Dalin investigated several violations of the new regulations and recommended penalties against three companies that had blasted holes in the wall. But even if the fines were paid—and it's not clear that they were—his intervention came too late. The wall in those three areas had already been destroyed.”

Commercial Development and the Great Wall of China

Brook Larmer wrote in Smithsonian Magazine: “In Shandong Province, I stare at a section of wall zig-zagging up a mountain. From battlements to watchtowers, the structure looks much like the Ming wall at Badaling. On closer inspection, however, the wall here, near the village of Hetouying, is made not of stone but of concrete grooved to mimic stone. The local Communist Party secretary who oversaw the project from 1999 on must have figured that visitors would want a wall like the real thing at Badaling. (A modest ancient wall, constructed here 2,000 years before the Ming, was covered over.) But there are no visitors; the silence is broken only when a caretaker arrives to unlock the gate. A 62-year-old retired factory worker, Mr. Fu—he gives only his surname—waives the 30-cent entrance fee. I climb the wall to the top of the ridge, where I'm greeted by two stone lions and a 40-foot-tall statue of Guanyin, the Buddhist goddess of mercy. When I return, Mr. Fu is waiting to tell me just how little mercy the villagers have received. Not long after factories usurped their farmland a decade ago, he says, the party secretary persuaded them to invest in the reproduction wall. Mr. Fu lost his savings. "It was a waste of money," he says, adding that I'm the first tourist to visit in months. "Officials talk about protecting the Great Wall, but they just want to make money from tourism." [Source: Brook Larmer, Smithsonian Magazine, August 2008 ]

“Certainly the Great Wall is big business. At Badaling, visitors can buy Mao T-shirts, have their photo taken on a camel or sip a latte at Starbucks—before even setting foot on the wall. Half an hour away, at Mutianyu, sightseers don't even have to walk at all. After being disgorged from tour buses, they can ride to the top of the wall in a cable car. In 2006 golfers promoting the Johnnie Walker Classic teed off from the wall at Juyongguan Pass outside Beijing. And last year the French-owned fashion house Fendi transformed the ramparts into a catwalk for the Great Wall's first couture extravaganza, a media-saturated event that offended traditionalists. "Too often," says Dong Yaohui, of the China Great Wall Society, "people see only the exploitable value of the wall and not its historical value."

“The Chinese government has vowed to restrict commercialization, banning mercantile activities within a 330-foot radius of the wall and requiring wall-related revenue to be funneled into preservation. But pressure to turn the wall into a cash-generating commodity is powerful. Two years ago, a melee broke out along the wall on the border between Hebei and Beijing, as officials from both sides traded punches over who could charge tourist fees; five people were injured. More damaging than fists, though, have been construction crews that have rebuilt the wall at various points—including a site near the city of Jinan where fieldstone was replaced by bathroom tiles. According to independent scholar David Spindler, an American who has studied the Ming-era wall since 2002, "reckless restoration is the greatest danger."

Great Wall satellite image

China Says Great Wall Is Twice as Long as Previously Thought

China now believes the Great Wall is 21,198 kilometers (13,171 miles) long, more than twice the previous estimation. The new measure elicits skepticism amid territorial disputes. Barbara Demick wrote in the Los Angeles Times: "The Great Wall of China may be one of the most recognizable structures on Earth, but it is still in the process of revealing new layers of itself - to cries of disbelief and fury in some quarters. At a time when Beijing is asserting its territorial borders in the South China Sea, the discoveries are not universally applauded. [Source: Barbara Demick, Los Angeles Times, July 17, 2012]

In early June, the State Administration of Cultural Heritage announced that it now believes the Great Wall is a stunning 13,171 miles long, if you put all of the discovered portions end to end. That's more than half the circumference of the globe, four times the span of the United States coast to coast and nearly 2 1/2 times the estimated length in a preliminary report released in 2009, two years into a project that saw the Chinese measure it for the first time.

To the extent that the Great Wall is a symbol of China, a bigger wall means, well, a bigger China, if only symbolically. "I'm very suspicious. China wants to rewrite history to make sure history conforms with the borders of today's China," said Stephane Mot, a former French diplomat and a blogger based in Seoul, who has accused the Chinese archaeologists of obliterating Korean culture.

Traditionally, the Great Wall was thought to extend from Jiayuguan, a desert oasis 1,000 miles west of Beijing, to Shanhaiguan, 190 miles east of the capital, on the Bohai Sea. In 2001, Chinese archaeologists announced that the wall extended deep into Xinjiang, the northwestern region claimed by the minority Uighurs as their homeland. Last month's announcement brought the eastern bounds of the wall to the North Korean border. That has outraged Koreans, who say the relics were built by ancient Koreans of the Koguryo kingdom, which occupied much of modern-day Manchuria from 37 BC to AD 688. "This is a distortion. The Chinese are using the wall to wipe out the Korean legacy, the same as they are doing with the Uighurs and Tibetans," said Seo Sang-mun, a military historian with Seoul-based Chung-Ang University.

Chinese defend the new measurements. "I would say that these are not necessarily 'new discoveries.' Rather, we are looking more carefully at what is on the ground and trying to clarify whether it is the Great Wall or not," Yan Jianmin, office director of the China Great Wall Society, a nongovernmental organization of scholars and wall enthusiasts.

The survey of the Great Wall's length involved thousands of people, with 15 provinces and regions submitting the results of their research to Beijing. In all, the State Administration certified 43,721 known sites of Great Wall remains, up from 18,344 before the survey. (Portions of the list were published on the agency's website, although it did not include the locations in Heilongjiang and Jilin provinces that are contested by the Koreans. Maps will not be released because they are considered a state secret.)

The difficulty is in defining what is "the Great Wall" and what is merely, well, an old wall. Describing the “discovery” of one purported wall section Demnick wrote: Zhang Lingmian was collecting walnuts in the countryside north of Beijing last autumn when a friend from a nearby village mentioned a mysterious structure in the mountains that had stumped locals. The retired cultural heritage official and his friend scampered uphill for two hours, whacking their way through the brambles after the path ran out. At the top of a 2,700-foot-high ridge, they reached a long trail of haphazardly placed rocks. Zhang says he immediately recognized what villagers called "the strange stones.""I knew right away it had to be part of the Great Wall of China," Zhang recalled on a recent hike to show off his discovery, about 50 miles from central Beijing. Although most of the rocks had tumbled down, a few piles reached up to Zhang's chest. "The walls just had to be high enough to keep the barbarians from crossing with their horses," explained Zhang, who says he has been studying the wall for 33 years.

What most people recognize as the Great Wall is the crenelated brick wall with watch towers and archer slits, the symbol of China from countless postcards and guide books. But there are many older walls dating from the 7th century that served the common purpose of defending China from invasion from the north. The late Luo Zhewen, who was considered the top Chinese authority on the subject, once wrote that nothing should be considered the Great Wall unless it was at least 30 miles long, clearly defensive in nature and not circular, as opposed to a wall to keep your sheep from wandering.

Mapping the Great Wall of China

In April 2009, China’s national mapping agency said The Great Wall of China is even greater than once thought, after a two-year government mapping study uncovered new sections totaling about 180 miles. Using infrared range finders and GPS devices, experts discovered portions of the wall concealed by hills, trenches and rivers that stretch from Hu Shan mountain in northern Liaoning province to Jiayu Pass in western Gansu province, the official China Daily reported. [Source: AP The Guardian, April 20, 2009]

The additional parts mean the Great Wall spans about 3,900 miles through the northern part of the country. The newly mapped parts of the wall were built during the Ming dynasty (1368-1644) to protect China against northern invaders and were submerged over time by sandstorms that moved across the arid region, the study said.

The latest mapping project, a joint venture by the State Administration of Cultural Heritage and State Bureau of Surveying and Mapping, will continue for another year in order to map sections of the wall built during the Qin and Han dynasties (221 BC-9 AD), the China Daily reported.

Recent studies by Chinese archaeologists have shown that sandstorms are reducing sections of the wall in Gansu to “mounds of dirt” and that they may disappear entirely in 20 years. These studies mainly blame the erosion on destructive farming methods used in the 1950s that turned large areas of northern China into desert. In addition, portions of the wall in Gansu were made of packed earth, which is less resilient than the brick and stone used elsewhere in much of the wall's construction.

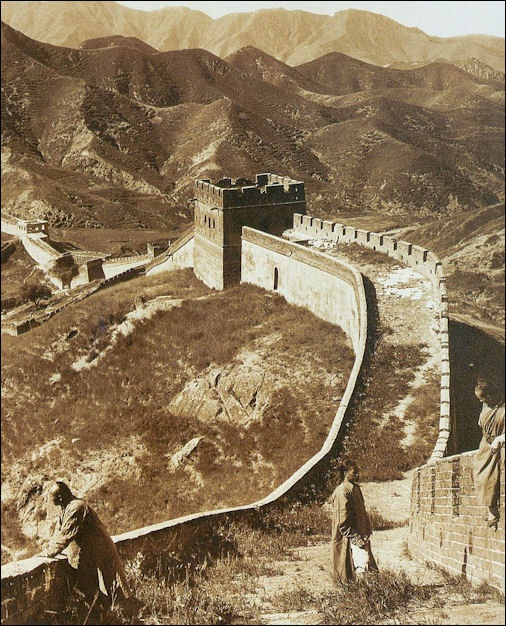

Great Wall in the early 20th century

Preservation of the Great Wall of China

Through much of its history—and even today—many Chinese had little interest in or affection for the Great Wall. One survey in 2006 found that only 28 percent of Chinese felt the wall needed to be preserved. However, the deteriorating condition of the Great problem is severe enough that the World Monument Fund added the wall to its list of “most endangered sites.” Organizations like the International Friends of the Great Wall have been established to help preserve it. In December 2006, a the first nationwide law in China was enacted to protect the Great Wall from practices such as removing bricks to build homes and pigsties, carving one’s name into the wall and holding all night parties that leave the walls smelling of urine and littered with garbage. A construction company in Inner Mongolia was fined $64,000 for removing a section that was in its way. These days the problem is not the laws but enforcement. In some section there are only three people covering 1,300-kilometer of wall.

Brook Larmer wrote in Smithsonian Magazine:“A small but increasingly vocal group of cultural preservationists act as defenders of the Great Wall. Some patrol its ramparts. Others have pushed the government to enact new laws and have initiated a comprehensive, ten-year GPS survey that may reveal exactly how long the Great Wall once was—and how much of it has been lost. "The Great Wall is a miracle, a cultural achievement not just for China but for humanity," says Dong Yaohui, president of the China Great Wall Society. "If we let it get damaged beyond repair in just one or two generations, it will be our lasting shame." [Source: Brook Larmer, Smithsonian Magazine, August 2008 ]

“Perhaps the greatest challenge lies in the fact that the wall extends for long stretches through sparsely populated regions, such as Ningxia, where few inhabitants feel any connection to it—or have a stake in its survival. Some peasants I met in Ningxia denied that the tamped-earth barrier running past their village was part of the Great Wall, insisting that it looked nothing like the crenelated stone fortifications of Badaling they've seen on television. And a Chinese survey conducted in 2006 found that only 28 percent of respondents thought the Great Wall needed to be protected. "It's still difficult to talk about cultural heritage in China," says He, "to tell people that this is their own responsibility, that this should give them pride."

Larmer’s guide in Ninxia “Ding confesses that he has no special feeling for the wall. He has lived in a mud-brick shack on its Inner Mongolian side for three years. Even in the wall's deteriorated condition, it shields him from desert winds and provides his sheep with shelter. So Ding treats it as nothing more, or less, than a welcome feature in an unforgiving environment. We sit in silence for a minute, listening to the sound of sheep ripping up the last shoots of grass on these rocky hills. This entire area may be desert soon, and the wall will be more vulnerable than ever. It's a prospect that doesn't bother Ding. "The Great Wall was built for war," he says. "What's it good for now?"

Dongjiakou, 270 kilometers northeast of Beijing, is one of the few places where protection efforts are taking hold. When the local Funin County government took over the CHP program two years ago, it recruited 18 local residents to help Sun patrol the wall. Preservation initiatives like his, the government believes, could help boost the sagging fortunes of rural villages by attracting tourists who want to experience the "wild wall." In many villages along the wall, especially in the hills northeast of Beijing, inhabitants claim descent from soldiers who once served there. Sun believes his ancestral roots in the region originated in an unusual policy shift that occurred nearly 450 years ago, when Ming General Qi Jiguang, trying to stem massive desertions, allowed soldiers to bring wives and children to the frontlines. Local commanders were assigned to different towers, which their families treated with proprietary pride. Today, the six towers along the ridge above Dongjiakou bear surnames shared by nearly all the village's 122 families: Sun, Chen, Geng, Li, Zhao and Zhang.

UNESCO on Great Wall of China Preservation

According to UNESCO: The existing elements of the Great Wall retain their original location, material, form, technology and structure. The original layout and composition of various constituents of the Great Wall defence system are maintained, while the perfect integration of the Great Wall with the topography, to form a meandering landscape feature, and the military concepts it embodies have all been authentically preserved. The authenticity of the setting of the Great Wall is vulnerable to construction of inappropriate tourism facilities....The visual integrity of the Wall at Badaling has been impacted negatively by construction of tourist facilities and a cable car. [Source: UNESCO]

The various components of the Great Wall have all been listed as state or provincial priority protected sites under the Law of the People’s Republic of China on the Protection of Cultural Relics. The Regulations on the Protection of the Great Wall promulgated in 2006 is the specific legal document for the conservation and management of the Great Wall. The series of Great Wall Conservation Plans, which is being constantly extended and improved and covers various levels from master plan to provincial plans and specific plans, is an important guarantee of the comprehensive conservation and management of the Great Wall. China’s national administration on cultural heritage, and provincial cultural heritage administrations where sections of the Great Wall are located, are responsible for guiding the local governments on the implementation of conservation and management measures for the Great Wall.

The Outstanding Universal Value of the Great Wall and all its attributes must be protected as a whole, so as to fulfill authentic, integral and permanent preservation of the property. To this end, considering the characteristics of the Great Wall, including its massive scale, transprovincial distribution and complicated conditions for its protection and conservation, management procedures and regulations, conservation interventions for the original fabric and setting, and tourism management shall be more systematic, scientific, classified, and prioritized. An efficient comprehensive management system, as well as specific conservation measures for the original fabric and setting will be established, while a harmonious relationship featuring sustainable development between heritage protection and social economy and culture can be formed. Meanwhile, the study and dissemination of the rich connotation of the property’s Outstanding Universal Value shall be enhanced, so as to fully and sustainably realize the social and cultural benefits of the Great Wall.

Great Wall of China Farmer Preservationist

Brook Larmer wrote in Smithsonian Magazine: “Sun Zhenyuan, a 59-year-old farmer turned preservationist, is conducting a daily reconnaissance along a crumbling 16th-century stretch of the wall overlooking his home, Dongjiakou village, in eastern Hebei Province. As leader of his local group, Sun is paid about $120 per year; others receive a bit less. Sun is confident that his family legacy will continue into the 22nd generation: his teenage nephew now joins him on his outings. Twenty-one generations ago, in the mid-1500s, Sun's ancestors arrived at this hilly outpost wearing military uniforms. His forebears, he says, were officers in the Ming imperial army, part of a contingent that came from southern China to shore up one of the wall's most vulnerable sections. [Source: Brook Larmer, Smithsonian Magazine, August 2008 ]

“As Sun Zhenyuan and I duck through the arched doorway of his family watchtower, his pride turns to dismay. Fresh graffiti scars the stone walls. Beer bottles and food wrappers cover the floor. This kind of defilement occurs increasingly, as day-trippers drive from Beijing to picnic on the wall. In this case, Sun believes he knows who the culprits are. At the trail head, we had passed two obviously inebriated men, expensively attired, staggering down from the wall with companions who appeared to be wives or girlfriends toward a parked Audi sedan. "Maybe they have a lot of money," Sun says, "but they have no culture."

“Sun began his preservationist crusade almost by accident a decade ago. As he trekked along the wall in search of medicinal plants, he often quarreled with scorpion hunters who were ripping stones from the wall to get at their prey (used in the preparation of traditional medicines). He also confronted shepherds who allowed their herds to trample the ramparts. Sun's patrols continued for eight years before the Beijing Cultural Heritage Protection Center began sponsoring his work in 2004. CHP chairman He Shuzhong hopes to turn Sun's lonely quest into a full-fledged movement. "What we need is an army of Mr. Suns," says He. "If there were 5,000 or 10,000 like him, the Great Wall would be very well protected."

“From the entrance to the Sun Family Tower, we hear footsteps and wheezing. A couple of tourists—an overweight teenage boy and his underweight girlfriend—climb the last steps onto the ramparts. Sun flashes a government-issued license and informs them that he is, in effect, the constable of the Great Wall. "Don't make any graffiti, don't disturb any stones and don't leave any trash behind," he says. "I have the authority to fine you if you violate any of these rules." The couple nods solemnly. As they walk away, Sun calls after them: "Always remember the words of Chairman Deng Xiaoping: ‘Love China, Restore the Great Wall!'" As Sun cleans the trash from his family's watchtower, he spies a glint of metal on the ground. It's a set of car keys: the black leather ring is imprinted with the word "Audi." Under normal circumstances, Sun would hurry down the mountain to deliver the keys to their owners. This time, however, he'll wait for the culprits to hike back up, looking for the keys—and then deliver a stern lecture about showing proper respect for China's greatest cultural monument. Flashing a mischievous smile, he slides the keys into the pocket of his Mao jacket. It's one small victory over the barbarians at the gate.”

Hiking and Studying the Great Wall of China

Some people have tried to hike the entire Great Wall. The American missionary and explorer William Edgar Geil traversed the length of the Great Wall — from “the tempestuous main of the Yellow Sea to the thirsty sands f the distant desert" — between 1907 and 1908. William Lindesay, a British geologist and marathoner, ran and hiked 2,470 kilometers of the wall in 1987 and would have done more but was deported. He later moved to Beijing, wrote four books about the wall and founded Friends of the Great Wall, a small organization oriented primarily towards conservation.

With the Great Wall as famous as it is it is surprising how little it has been studied. Brook Larmer wrote in Smithsonian Magazine: “The Great Wall is rendered even more vulnerable by a paucity of scholarship. There is not a single Chinese academic—indeed, not a scholar at any university in the world—who specializes in the Great Wall; academia has largely avoided a subject that spans so many centuries and disciplines—from history and politics to archaeology and architecture. As a result, some of the monument's most basic facts, from its length to details of its construction, are unknown. "What exactly is the Great Wall?" asks He Shuzhong, founder and chairman of the Beijing Cultural Heritage Protection Center (CHP), a nongovernmental organization. "Nobody knows exactly where it begins or ends. Nobody can say what its real condition is." [Source: Brook Larmer, Smithsonian Magazine, August 2008 ]

Dong Yaoshi, a former utility worker, hiked thousands of miles of the wall beginning in 1984 and founded the Great Wall Society of China. Dong Feg, a policeman at Beijing University, is regarded a the most active Chinese researcher today. He runs Greatwall.com and discovered that breaks in the wall are there because they lie along dragon lines, important for the feng shui of Beijing.

David Spindler's Great Wall of China

Great Wall from Space

David Spindler, a 6-foot-7 American independent scholar, is regarded by some as the premier expert of the wall. He has hiked much its length, often bushwhacking through brambles and thorns with a special outfit that includes a face mask made from the leg of a pair of sweat pants.

David Spindler is a self-motivated and self-funded scholar of the Great Wall, who has probably walked and climbed on more parts of the Wall around Beijing than any other living person. His approach to his studies has been unorthodox: he has an M.A. in history from Peking University, but his Great Wall research has been conducted outside of the university system. Nonetheless, his combination of highly athletic field research — the Wall around Beijing is built on some very steep and tall mountains — and more conventional academic research has started to bear fruit. [Source: Posted by Jeremy Goldkorn, Danwei.org, October 6, 2009]

In the first public exhibition of his research, Spindler has collaborated with photographer Jonathan Ball to produce a series of large-scale, historically-based photographs of the Great Wall. The photos are on display in an exhibition titled “China's Great Wall: The Forgotten Story,” shown at the 3A Gallery in San Francisco in 2009 and he offices of the Rockefeller Brothers in New York in 2009 and 2010.The photographs show parts of the the Wall where important Mongol and Manchu raids occurred in the 15th, 16th and 17th centuries, taken on the anniversaries of the raids, at approximately the time of day when the fighting happened. Each photograph stands over three feet tall, and stretches from 9 feet to over 30 feet wide. They are captioned with stories about the battles, drawn from Spindler's research.

Spindler says these photographs put you as close as possible in the modern era to the point of view of people who attacked or defended the Great Wall during these battles—the vegetation is the same, the light is the same, the time of year and even the time of day is the same.”

Explaining one photograph to Danwei Spindler said, “On the night of September 26, 1550, a group of Mongol warriors took picks and shovels and pushed apart the unmortared stone wall protecting the gully in this photograph. They suddenly appeared behind the main Chinese defensive force just east of this spot, surprised them, routed the defenders, and for the next two weeks looted, burned, and pillaged the northern suburbs of Beijing. The only extant account that quantifies the casualties (though certainly an exaggerated one) mentions sixty thousand Chinese killed, forty thousand taken captive, and millions of head of livestock lost as a result of this raid. One of the main Chinese responses to this raid was to rebuild much of the eastern sections of the Great Wall with mortar over the following twenty or so years.” [Source: Posted by Jeremy Goldkorn, Danwei.org, October 6, 2009]

Tourism and the Great Wall of China

By some measures the Great Wall of China is China’s most-visited tourist attraction. About 10 million tourists visit the Great Wall every year with the majority of them going to the Badaling section which has received 119,000 people in a single day. The Great Wall is a UNESCO World Heritage Site. In recent years the government has been taking a more activist role in preserving it, banning hiking on unrestored section and rebuilding parts that have been crumbling. In 2005 the entrance fees to the Great Wall sections near Beijing were substantially raised to as high as 80 yuan ($9.60). The money is supposed be used for upkeep and restoration.

Many dignitaries and celebrities including Richard Nixon, George Michael have been photographed at the wall. On his only visit to China in 1982, Andy Warhol wrote: “I went to the Great Wall. You know, you read about ir for years. An actually, it was rally great. It was really, really, really great.”

A number of events have been held there. In 2004, a rock concert headlined by Cyndi Lauper was held on a revolving stage set on a watch tower. In 2006, the Johnnie Walker Golf Classic teed off from the wall at Juyongguan Pass. In 2007, the wall was used as a catwalk for a Fendi and Karl Lagerfield fashion show.

All-night raves have been held o the wall. Every spring the Great Wall Marathon is staged at a section of the wall 130 kilometers from Beijing. In some of the steeper sections many participants walk. In 2002, a stunt cyclist died trying to jump the Great Wall. In 2007 a skateboarder successfully leapt over it.

There are special places near the Great Wall where celebrities and rich people can stay. Commune of the Great Wall (at the foot of the Great Wall near Badaling) is collection of fanciful homes, each designed by a respected Asian architect. The one designed by Californian-trained Yung Ho Chang is made of packed earth. The one designed by Shigeru Ban is made of laminated bamboo. Originally called Architectural Gallery, it was designed to be a weekend escape. The houses were put on the market for $1 million each, There were few buyers and it new serves as a convention center and tourist attraction as well as a place for the rich and famous.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, Great Wall map, Dr. Robert Perrins; Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated May 2020