COAL IN CHINA

coal briquettes

China is the world's leading user and producer of coal. By some accounts China uses as much coal as the rest of the world combined. According to a report released in March 2021 by the U.K.-based energy and climate research group Ember, China accounted for 53 percent of the world’s coal-powered electricity in 2020 — nine percentage points higher than its share in 2015, when China joined the Paris Agreement. [Source: Eamon Barrett, Fortune, March 29, 2021]

Coal is the single most important energy source; coal-fired thermal electric generators provide much China's electric power. Although coal's share of China's overall energy consumption has decreased, coal consumption has continued to rise in absolute terms. China's continued and increasing reliance on coal as a power source has contributed significantly to making China the world's largest producer of acid rain-causing sulfur dioxide and the largest emitter of green house gases, including carbon dioxide.

According to Reuters China’s output of coal in 2021 was 4.1 billion tons, an increase of 5.7 percent over 2020 when China used 4.2 billion tons of coal, of which 335 million tons was imported. In 2010, China burned 24 percent of the world's coal, compared to 25.5 percent in the United States and 7 percent in India. In 2006, over 2.2 billion metric tons of coal was taken from Chinese coal mines “more than the United States, India and Russia combined. This was up from 2.1 billion in 2005, 1.7 billion in 2003 and 1.4 billion in 2002 and 70 percent more than 2000. The figure is expected to rise to 2.6 billion in 2010 and 3.1 billion in 2020, with coal production increasing at a rate of 10 percent to 15 percent a year.

China has the world’s third or fourth largest coal reserves. China has 126 billion tons of coal, enough to last 75 years if consumption rates remain the same. Coal reserves: 1) the United States (27 percent); 2) Russia (17 percent); 3) China (13 percent); 4) Australia (9 percent); 5) South Africa (5 percent); Other (19 percent). Recoverable coal deposits (tons in 2006): 1) the United States (268 billion); 2) Russia (173 billion); 3) China (126 billion); 4) India (102 billion); 5) Australia (87 billion); 6) Europe (66 billion); 7) South Africa (54 billion); 8) Ukraine (38 billion); 9) Kazakhstan (34billion); 10) South America (22 billion). [Source: Energy Information Administration, Department of Energy]

China plans to rely on more electric generation from nuclear, renewable sources, and natural gas to replace some coal-fired generation to reduce carbon dioxide emissions and the heavy air pollution in urban areas. [Source: U.S. Energy Information Administration country analysis briefs, September 30, 2020]

See Separate Articles: COAL IMPORTS TO CHINA FROM AUSTRALIA, THE U.S. AND MONGOLIA factsanddetails.com; COAL MINES IN CHINA factsanddetails.com; COAL MINE SAFETY, DEATHS AND INJURIES IN CHINA factsanddetails.com; MAJOR COAL MINE DISASTERS AND ACCIDENTS IN CHINA factsanddetails.com;Articles on ENERGY IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; U.S. Energy Information Administration Report on Energy in China eia.gov/international/analysis ; China Coal Resource sxcoal.com ; Wikipedia article Wikipedia

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: “The Chinese Coal Industry: An Economic History” by Elspeth Thomson Amazon.com; The Political Economy of the Chinese Coal Industry: Black Gold and Blood-Stained Coal” by Tim Wright Amazon.com; “China Coal Mining And Coal Washing Practices”by Heng Huang, Chun A Shan, Liu Guo Min et al. (2018) Amazon.com; “Empires of Coal: Fueling China’s Entry into the Modern World Order, 1860-1920" by Shellen Xiao Wu Amazon.com; “Globalisation, Transition and Development in China: The Case of the Coal Industry” by Rui Huaichuan (2004) Amazon.com; “Energy Policy in China” by Chi-Jen Yang (2017) Amazon.com; “China’s Electricity Industry: Past, Present and Future” by Ma Xiaoying and Malcolm Abbott (2020) Amazon.com

Coal Consumption in China

Coal consumption increased at a rate of 10 percent a year through the 1990s and 2000s. In 2006, China added new power plants with more capacity than all the coal plants in Britain. The production of coal-fired plants slowed to some degree in the 2010s. They were no longer being produced at the rate of one a week. About 80 gigawatts of power was added each a year, down from 100 gigawatts a few years earlier. Even though China has huge coal resources, its consumption outstrips production. In 2007, China imported more coal than it exported for the first time.

After several years of declines, China’s coal consumption grew by 1 percent each year in 2018 and 2019, based on physical volume (more than 4.3 billion short tons in 2019), according to estimates of China’s National Bureau of Statistics (NBS). Electricity and industrial demand growth, especially from steel production, were strong.In addition, some provincial governments eased air quality measures starting in the winter of 2018–19 as a result of natural gas supply shortages and high natural gas prices during peak energy demand periods in 2017. The power sector accounted for nearly 60 percent of China’s coal consumption in 2018, and the remainder of China’s coal use is from industry, such as steel and cement production, and residential heating. [Source: U.S. Energy Information Administration country analysis briefs, September 30, 2020]

China’s coal demand for coal in 2020 and 2021 was determined by the magnitude of the COVID-19 pandemic in China and its impact on the electricity and industrial demand growth and the government’s continued policy on air quality issues and fuel switching. Coal will eventually be phased out of the residential sector for heating purposes as the government targets more households each year to convert from coal boilers to natural gas or electric boilers. Competition with cleaner-burning fuels, China’s shift to a less energy-intensive economy, and the trade conflict with the United States will pose downside risks to coal demand in the next several years. However, coal will likely remain a pillar of the electric power and heating demand because of the country’s abundant resources and the government’s intention to increase use of clean coal technology

The price of coal rose to $60 from $40 a ton in 2005 to a high of $200 in 2008. Coal delivered to southern China sold for $114 per ton in November 2010. Carl Pope, the outgoing president of the Sierra Club, told the New York Times there is a myth that coal is cheap and abundant: While there is a lot of coal geologically, and a fair amount of coal close enough to either ports or load-centers so that it is cheap at the power plant, there is not enough of this accessible, cheap coal to meet growing demand in Asia. Two factors make much of India’s and China’s coal expensive or inaccessible; it takes a lot of water, which is in short supply, to extract and burn the coal at mine-mouth, and it takes a lot of diesel fuel, increasingly expensive, to train/truck/ship it to coastal power plants and load centers.” [Source: Andrew C. Revkin, New York Times, November 22, 2011]

Coal Production in China

China is the world's biggest coal producer, followed by India, Indonesia, the United States and Australia. Coal production in China declined for three consecutive years until 2016 then rose each year after that reaching an estimated 4.1 billion short tons in 2019. China’s government adopted a supply-side approach to control the volatility of domestic coal prices through a targeted price range, which allowed domestic producers to be profitable and compete with coal imports. [Source: U.S. Energy Information Administration country analysis briefs, September 30, 2020]

China has abundant supplies of coal and produced more than 90 percent of the 4.4 billion tons it burned in 2021. Because coal demand from the power sector and coal prices began rising at the end of 2016, China relaxed several policies that restricted domestic coal production. China raised production capacity and began to replace uncompetitive and outdated mine capacity. Output growth was from the largest coal-producing mines in the north central and northwestern areas of the country. China continues to replace outdated coal capacity with new, more efficient mine capacity and to close smaller mines in the eastern and southern regions.63 Furthermore, China’s recent expansion of long-range railway capacity, such as the Haoji Railway commissioned in October 2019, to connect the coal-producing centers in the interior to eastern demand centers is instrumental to bolstering domestic production and responding to coal demand.

Coal production and consumption: (production and consumption tons in 2006): 1) China (2,621 million and 2,578 million) ; 2) the United States (1, 161 million and 1,114 million ); 3) India (497 million and 542 million ); 4) Australia (420 million and 156 million); 5) Russia (341 million and 264 million); 6) South Africa (269 million and 195 million); 7) Germany (223 million and 272 million); 8) Indonesia (186 million and 44 million); 9) Poland (171 million and 155 million); 10) Kazakhstan (106 million and 79 million). [Source: Energy Information Administration, Department of Energy]

Electricity: from fossil fuels: 62 percent of total installed capacity (2016 est.), 124th in the world. [Source: CIA World Factbook, 2022]

Development of Coal in China

In the first half of the twentieth century, coal mining was more developed than most industries. Such major mines as Fushun, Datong, and Kailuan produced substantial quantities of coal for railroads, shipping, and industry. Expansion of coal mining was a major goal of the First Five-Year Plan. The state invested heavily in modern mining equipment and in the development of large, mechanized mines. The longwall mining technique was adopted widely, and output reached 130 million tons in 1957. [Source: Library of Congress, 1987 *]

During the 1960s and 1970s, investment in large mines and modern equipment lagged, and production fell behind the industry's growth. Much of the output growth during this period came from small local mines. A temporary but serious production setback followed the July 1976 Tangshan earthquake, which severely damaged China's most important coal center, the Kailuan mines. It took two years for production at Kailuan to return to the 1975 level.*

In 1987 coal was the country's most important source of primary energy, meeting over 70 percent of total energy demand. The 1984 production level was 789 million tons. More than two-thirds of deposits were bituminous, and a large part of the remainder was anthracite. Approximately 80 percent of the known coal deposits were in the north and northwest, but most of the mines were located in Heilongjiang and east China because of their proximity to the regions of highest demand.*

Although China had one of the world's largest coal supplies, there still were shortages in areas of high demand, mainly because of an inadequate transportation infrastructure. The inability to transport domestic coal forced the Chinese to import Australian coal to south China in 1985. The industry also lacked modern equipment and technological expertise. Only 50 percent of tunnelling, extracting, loading, and conveying activities were mechanized, compared with the 95-percent mechanization level found in European nations.*

In 2000, China was both the world's largest coal producer, at 1.27 billion short tons, and the leading consumer of coal, at 1.31 billion short tons. In 2003, China produced an estimated 1.63 billion short tons of coal and consumed an estimated 1.53 billion short tons for the same year. As of August 2005, it was reported that coal accounted for 65 percent of primary energy consumption. [Source: Worldmark Encyclopedia of Nations, Thomson Gale, 2007]

China's Dependence on Coal

Coal provides China large portions of its total energy and electricity. It is relatively plentiful and cheap but very dirty. The government wants to replace coal with oil, natural gas and hydroelectric power primarily to clean up its air. Even so demand for coal keeps increasing as the economy grows and 60 new coal-fired power stations go on line every year. China could become a net coal importer between 2010 and 2015. China relies on coal to achieve its goal of energy independence. Thanks to coal China is 90 percent self-sufficient in energy — 20 percent more than most of the developed countries in OECD.

Even if drastic measures are taken China will still have to rely on coal for 65 percent of its energy needs for the foreseeable future. A Chinese coal engineer told the New York Times, "We are a developing country and we started without a very good foundation. We have so few choices and no funding, so our industries are going to rely heavily on coal for a long time to come." By some estimates China will have to triple its use of coal if it wants to achieve a standard of living near that of the United States. Some predict that by 2030 China’s demand for coal will exceed that of the rest of the world combined. Even though China far and away produces more coal than any other country demand is so strong it has limited exports.

Even if drastic measures are taken China will still have to rely on coal for 65 percent of its energy needs for the foreseeable future. A Chinese coal engineer told the New York Times, "We are a developing country and we started without a very good foundation. We have so few choices and no funding, so our industries are going to rely heavily on coal for a long time to come." By some estimates China will have to triple its use of coal if it wants to achieve a standard of living near that of the United States. Some predict that by 2030 China’s demand for coal will exceed that of the rest of the world combined. Even though China far and away produces more coal than any other country demand is so strong it has limited exports.

It estimated that even with new land gas pipelines opening and alternative energies being exploited China will get at least 50 percent of its energy from coal in 2020 and beyond. Deborah Seligsohn of the World Resources Institute told AFP, “China has a lot of coal, has very limited supply of other fossil fuels and even with rapid growth rates in renewables, it will be difficult to actually replace the coal in use for quite some time.” David Fridley, a China energy expert at the University of California, Berkeley, told the New York Times, “Only coal can provide new capacity in the time and scale needed.”

Coal production has been slowed by crackdowns on illegal mines and transportation bottlenecks that keep coal from reaching all the places it is needed, This has led to a rise of coal prices. The increase of coal prices in turn has devastated the electricity-generating industry because companies that produce electricity are tightly regulated by the government and are not allowed to raise prices without government approval. The government, fearing a backlash from consumers, doesn’t want to raise prices. After coal prices spiked in 2003 and 2004, 85 percent of coal power plants lost money.

China Promotes Coal in 2022 — a Setback in the Fight Against Climate Change

In 2022, China began promoting coal-fired power once again as the ruling Communist Party tries prioritized reviving a sluggish economy over cutting climate-change-inducing carbon emissions. Associated Press reported: Official plans call for boosting coal production capacity by 300 million tons in 2022, according to news reports. That is equal to 7 percent of 2021's output of 4.1 billion tons, which was an increase of 5.7 percent over 2020.[Source: Joe McDonald, Associated Press, April 24, 2022]

“China is one of the biggest investors in wind and solar, but jittery leaders called for more coal-fired power after economic growth plunged in 2021 and shortages caused blackouts and factory shutdowns. Russia’s attack on Ukraine added to anxiety that foreign oil and coal supplies might be disrupted. “This mentality of ensuring energy security has become dominant, trumping carbon neutrality,” said Li Shuo, a senior global policy adviser for Greenpeace. “We are moving into a relatively unfavorable time period for climate action in China.”

“Coal is important for “energy security,” Cabinet officials said at an April 20 meeting that approved plans to expand production capacity, according to Caixin, a business news magazine. The ruling party also is building power plants to inject money into the economy and revive growth that sank to 4 percent over a year earlier in the final quarter of 2021, down from the full year's 8.1 percent expansion.

“China has abundant supplies of coal and produced more than 90 percent of the 4.4 billion tons it burned in 2021. More than half of its oil and gas is imported and leaders see that as a strategic risk. Beijing has spent tens of billions of dollars on building solar and wind farms to reduce reliance on imported oil and gas and clean up its smog-choked cities. China accounted for about half of global investment in wind and solar in 2020. Still, coal is expected to supply 60 percent of its power in the near future.”

Coal and Chinese Life

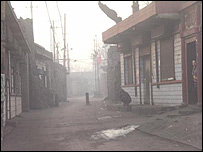

Coal was used at a rate of about 1.5 tons per person a year in the 2000s. It is used to generate power for factories and electric plants as well as cook meals and heat homes. China burns the stuff so fast railroads can not deliver it fast enough. Jerry Goodell wrote in Natural History magazine: “In China coal is everywhere. It’s piled up on sidewalks, pressed into bricks, and stacked neat the back doors of homes. It’s stockpiled into small mountains in open fields, and carted around behinds bicycles and wheezing locomotives. Plumes of coal smoke rise from rusty stacks on every urban horizon. Soot covers every windowsill and ruins the collar of every white shirt. The Chinese burn less coal per capita than America does but in sheer tonnage, they burn twice as much.”

Kenneth R. Weiss wrote in the Los Angeles Times: “A red truck arrived with a squeal of brakes and a swirling cloud of black dust. The driver peeled back a tarpaulin to reveal his cargo: coal to stoke one of the massive electricity plants in Shanxi province. The procession of dump trucks continued around the clock, leaking coal dust that piled up along the road like drifts of black snow. Squat cooling towers hissed like fumaroles. Slender smokestacks disgorged white-gray smoke carried east by the breeze, toward Beijing and beyond. In nearby Datong, a thick gray-brown haze clings to the city like a dark mist, obscuring the tops of high-rises. [Source: Kenneth R. Weiss, Los Angeles Times, July 22, 2012]

“A half-day's drive south is the ancient city of Linfen, identified by the World Bank six years ago as the most polluted city on Earth. The city, once known for its fruit and flowers, is now infamous for respiratory illnesses and the shroud of smog that regularly blots out the sun. When the sun does manage to poke through, it appears as a burnt orange fireball, reminiscent of Southern California's eerie skies during raging wildfires. Tendrils of soot extend across the Pacific.

Water and pulverized coal are formed into cakes and bricks at farms throughout China. Both peasants and city dwellers use these cakes for cooking and heating. In many places coal bricks are still delivered to people’s homes by tricycles or bicycles. One skinny 38-year-old coalman told The Times of London, “I just ride around with no fixed destination, just wherever people need coal to heat their homes.” Delivering coal is his winter job. He also works on a farm in the spring and summer.

Coal has enriched a few, provided hard, low-paying jobs for many but brought misery to many more in the form of dirty air and water and scarred landscapes. Poor scavengers rummage through hill-size slag heaps for usable chunks of coal to heat their own homes or sell. Describing one, Brook Larmer wrote in National Geographic, “High on one steep incline, nearly 500 feet up, a scavenger named Chang Mingdong trawls for usable fragments of coal, dodging fresh loads of rock careening down the embankment, sidestepping the coal embers smoldering beneath the surface.”

See Air Pollution, Environment, Nature

Coal Industry in China

The coal industry is a major employer in China. It is estimated that about 5.8 million people in China work in the coal sector. Large thermal power plants are situated in the northeast and along the east coast of China, where industry is concentrated, as well as in new inland industrial centers, such as Chongqing, Taiyuan, Xi'an, and Lanzhou. Coal mining employs 3 million people in China. There are about 30,000 legal coal mines in the country and the industry is growing rapidly. The 17,000 or so small mines account for a third of China’s coal output. There are thousands more illegal mines.

Shenhua is China’s largest coal producer and the world's biggest coal company. Based mainly in Inner Mongolia, it's production in 2006 was 150.5 metric tons, a 12.5 percent increase from the previous years, and is sales was 171.1 million metric tons, an 18.5 percent increase from the previous year. China Coal Energy is China’s second largest coal producer by revenue. Yanzhou Coal is another large coal company.

Coal-fired thermal electric generators in coal-burning plants produce about two-thirds of China’s electricity, compared to one-half in the United States. On average coal-fired power plants in China are more efficient than ones in the United States. China is trying to develop cheaper, smaller, easy-to-build power plants. Coal fired plants can be built quickly and with relative ease compared to a nuclear power plant or large dam project.

To reduce smog, the low chimneys of small thermal power generators are being replaced by the towering smokestacks of more efficient “supercritical” plants. Although China is building one a new coal-fired plant each week, most of them are more efficient than similar facilities in the UK. They are also better equipped to remove sulphur dioxide and other noxious gases. [Source: Jonathan Watts, The Guardian, November 15, 2009]

Coal was selling for $125 a ton in June 2022, up from $38 a ton in 2005 and $8.50 a ton in 2000. The price doubled in 2003. The price of coal rose from $40 a ton in 2005 to as high of $200 a ton in 2008. Coal delivered to southern China currently sold for $114 per ton in November 2010. Coal demand was expected to drop somewhat as the Three Gorges dam and five new nuclear power plants begin generating electricity in the mid 2000s. But that largely didn't happen as demand for energy in China has been so strong to keep its economy going. In Inner Mongolia, a $2 billion plant is being constructed that turns coal into gasoline.

Coal-Producing Regions in China

Coal-fired stove Coal comes from over two dozen sites in the north, northeast, and southwest; Shanxi Province is the leading producer. Recoverable reserves as of 2003, were estimated at over 126.2 billion short tons. Much of China’s coal comes from Shaanxi, Shanxi, Inner Mongolia and Hebei provinces. Xinjiang has an estimated 2.2 trillion tons of coal reserves. 40 percent of China’s total. The Junggar Basin in northern Xinjiang contains the largest coal reserves in China, with more 300 billion tons of ore.

The whole province of Shanxi is like a giant coal seam. Patrick Tyler of the New York Times, "Within a 300 mile radius” of Shanxi’s capital Datong “hundreds of thousands of coal miners are shredding subterranean seams thicker than ocean liners and hauling a black treasure to the surface to power the economic rise of China."Shaanxi Province, in Central China, once was the main coal source for power plants, but recent production and worker-safety problems there led the government to tap bigger coal deposits in Inner Mongolia. [Source: Michael Wines, New York Times, August 27, 2010]

The city of Linfen lies in the heart of Shanxi’s coal country. It is located in an area with 400 mines and billions of tons of proven reserves that account for half of Shanxi’s coal production. Not surprisingly it is also one of the most polluted cities in China, if not the in the world. Black, sooty dusts hangs in the air.

Inner Mongolia in China’s far north is now the number one region for coal production in China. Michael Wines wrote in the New York Times, “Mongolian coal production has exploded — up 37 percent to 637 million tons last year alone, with an additional 15 percent increase expected this year. Much of the coal is supposed to move to seaports on China’s east coast, to be shipped to big cities in the south. But pig-in-python style, even China’s brand-new freeway system cannot handle the volume.” The Wude coal field in Inner Mongolia is one of China’s largest coal fields, extending over an area of 15quare miles. There, trucks carry loads from the open pit mines. Scavengers in donkey carts pick up pieces of coal that bounce off the trucks. The air is filled with black dust and acrid sulfur dioxide fumes from the coal fires that burn below the surface.

Transporting Coal in China

Coal-producing area in Shaanxi The logistics of coal are a problem in China. Most of China’s coal deposits in the north, west and the interior of China while the industries are in the south and on the coast. Half of China’s railways capacity is used to transport coal. At peak times, 200-carriage trains pulled by powerful engines pass every 10 minutes on single rails through northern China, en route to ports and major power plants on the wealthy eastern seaboard.

China currently moves only 55 percent of its coal by rail, which is down from 80 percent a decade ago, as many coal users have been forced by inadequate rail capacity to haul coal in trucks instead. The trucks burn 10 or more times as much fuel per mile to haul a ton of coal.

One of the biggest challenges in China is moving coal from inland production areas to power stations and industries in the coastal regions. Most of it is moved by train. Sometimes there is so much coal to be moved there is danger of overwhelming the transportation system. The rail system devotes 40 percent of its capacity to moving coal but still can’t keep up with demand or supply enough railway cars to transport the coal. Bottlenecks in coal transportation have contributed to energy shortages.

Transporting the million s of tons of coal needed to keep China’s factories and power plants humming is struggle which strains the rail system and is vulnerable to bad weather. During the blizzard of 2008 coals shipments dwindled to half of what they are normally. As a result foreign exports were suspended and electricity was rationed in 17 provinces, most of them in the south. Even with energy conservation measures in place there were severe electricity shortages in the Guangdong area.In a typical example of the impact of the shortage of industry, a cement factory in Guangdong had no electricity between 7:00am and noon and 5:00pam and midnight. When they did get electricity it was 60 percent what they normally got.

Large amounts of coal produced around Datong are moved by rail to the northeast coastal port of Qinghuangdao and then moved by ship to industrial areas in the coastal province of Fujian and Guangdong. The rail line carries about 200 million metric tons a year. Another important rail line links the city of Houma in Shanxi to the ports of Rizhao and Qingdao in Shandong province and Lianyungang in Jiangsu Province.

Mines produce mountains of coal. The roads used by coal trucks are covered in black dust. In some places coal is delivered by trucks straight from mines to people’s homes. Coal prices rose to $53.29 a metric ton in May 2007 in part because of a backlog of ships waiting for coal at the coal station at Newcastle, Australia, with many of is the ships waiting to pick up coal to take to China. Export taxes on coking coal were raised to prevent coal needed at home to prevent power shortages from being exported.

Coal, the Environment and Health in China

Bringing coal to homes It is estimated that the use of cheap coal cost China $248 billion, the equivalent of 7.1 percent of GDP, in 2007 through environmental damage, strains on the health care system and manipulation of commodity prices. The figure was arrived at by the Energy Foundation and the WWF by taking into consideration things like lost income from those sickened by coal pollution.

Coal has been tied to a number of health problems. In towns like Gaojiagao in Shanxi it has been linked with a high number of birth defects such neural tube defects, additional fingers and toes, cleft pallets and congenital heart disease and mental retardation.

China's coal problems is a global problem. China burns more coal than America, Europe, and Japan combined. Julio Friedmann, an energy expert at the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory, near San Francisco, told The New Yorker, “The decisions that China and the U.S. make in the next five years in the coal sector will determine the future of this century.” [Source: Evan Osnos, The New Yorker, December 21, 2009]

See Separate Articles: AIR POLLUTION IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; AIR POLLUTION IN BEIJING AND CHINESE CITIES factsanddetails.com ; IMPACT OF CHINESE AIR POLLUTION ON HEALTH, THE ECONOMY AND EXPATS factsanddetails.com ; GLOBAL WARMING AND CHINA factsanddetails.com

Efforts to Cut Coal Use in China

In March 2017, China’s top economic planner said China would cut steel capacity by 50 million tonnes and coal output by more than 150 million tonnes in 2017 as part of China’s efforts to tackle pollution and curb excess supply. In a work report at the opening of the annual meeting of parliament, the National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC) said it would shut or stop construction of coal-fired power plants with capacity of more than 50 million kilowatts. [Source: Reuters, March 5, 2017]

“In its report, the NDRC said it would cut energy consumption per capita by 3.4 percent and curb carbon intensity by 4 percent in 2017 By 2020, the government has said it aims to close 100 million-150 million tonnes of steel capacity and 800 million tonnes of outdated coal capacity. The 2017 targets came after the world's top coal consumer and steel maker far exceeded its 2016 goals to eliminate 250 million tonnes of coal and 45 million tonnes of steel capacity. . Coal output fell 9 percent to 3.64 billion tonnes in 2016.

Reporting from the heart of coal country in Shanxi, Kenneth R. Weiss wrote in the Los Angeles Times: “ Under international pressure, China has cracked down on some of its dirtiest plants, mainly to reduce soot or pollutants like sulfur dioxide, which causes acid rain and aggravates asthma and heart disease. After the World Bank's rebuke, officials in Shanxi province closed some of the illegal coal mines in Linfen and its dirtiest coal-fired furnaces. Chen Mai Zhi, a stout middle-aged woman in black capri pants, said her headaches and dizzy spells have receded, but she still avoids wearing light-colored clothes and doesn't hang laundry outdoors because of the soot. Wang Shu Quing has also noticed a difference. The smokestacks bordering her cornfield just north of Linfen no longer cough up black smoke. "They did something inside to change it," Wang said. "Now you can see the smoke only once in a while."[Source: Kenneth R. Weiss, Los Angeles Times, July 22, 2012]

See Separate Articles COMBATING AIR POLLUTION IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; COMBATING GLOBAL WARMING IN CHINA factsanddetails.com

China’s Switch from Heating Coal to Natural Gas and Electricty

In June 2021, an official at China National Petroleum Corp (CNPC) said China plans to cut its coal use to 44 percent of energy consumption by 2030 and 8 percent by 2060 with a large portion of the reduction coming from the use of more natural gas to achieve its climate change goals. China is expected to increase the use of natural gas in its primary energy mix to 12 percent in 2030 from 8.7 percent in 2020, said Zhu Xingshan, senior director, Planning Department CNPC. He added that the share of natural gas in energy consumption is expected to increase "significantly" from 2030 to 2035. [Source: Reuters, June 24, 2021]

China, the world's largest energy consumer and biggest emitter of climate warming greenhouse gases, has vowed to bring its total carbon emissions to a peak before 2030 and to be carbon neutral by 2060. Natural gas is expected to be a key bridge fuel over the next two decades, CNPC has said. The energy giant expects coal to make up 44 percent, petroleum at 18 percent, natural gas at 12 percent and non-fossil fuel to make up 26 percent of the total energy mix in 2030. The estimates for 2060 were coal at 8 percent, petroleum at 6 percent, natural gas at 11 percent and non-fossil fuel at 75 percent of the total energy mix. China lowered the share of coal use in its primary energy mix to 56.8 percent in 2020, from around 68 percent at the beginning of the previous decade and expects this share to fall to below 56 percent in 2021.

Evan Osnos wrote in The New Yorker, in 2007 “a truckload of Beijing municipal workers turned up in my neighborhood and began unspooling heavy-duty black power lines, which they attached to our houses, in preparation for a campaign to replace coal-burning furnaces with electric radiators. Soon, the Coal-to-Electricity Project, as it was called, opened a small radiator showroom in a storefront around the corner, on a block shared by a sex shop and a vender of funeral shrouds. My neighbors and I wandered over to choose from among the radiator options. “Two-thirds of the price was subsidized by the city, which estimates that it has replaced almost a hundred thousand coal stoves since the project began, five years ago, cutting down on sulfur and dust emissions. I settled on a Marley CNLS340, a heater about the size of a large suitcase, manufactured in Shanghai. It had a built-in thermostat preprogrammed to use less electricity during peak day hours and then store it up at night, when demand was lower — a principle similar to the “smart meters” that American utilities plan to install in the next decade.” [Source: Evan Osnos, The New Yorker, December 21, 2009]

See Separate Article NATURAL GAS IN CHINA factsanddetails.com

Coal Diesel, Coal Liquification and Coal Gasification in China

China uses coal like oil to make liquid fuels and chemicals. The Chinese government is negotiated with the South African firm Sasol to build coal- to-oil plants that can produce 80,000 barrels of oil a day to China in the early 2010s. Oil production from coal-to-liquids (CTL) plants was an estimated 108,000 barrels per day and from methanol-to-liquids was around 500,000 barrels per day in 2019. China is attempting to monetize its vast coal reserves by converting some of it to cleaner-burning fuels and using them for bolstering energy security in the petroleum sector. At the end of 2016, Shenhua Group brought online the world’s largest CTL plant, Ningxia, with a capacity to produce more than 80,000 barrels per day of oil. China’s CTL plant capacity could triple in size between 2017 and 2023, barring project delays. Most of China’s methanol is sourced from coal, and the government is encouraging more conversion of methanol to fuel and petrochemicals. [Source: U.S. Energy Information Administration country analysis briefs, September 30, 2020]

Jonathan Watts wrote in The Guardian.” “Coal-to-liquid technology has a long history. It was developed in Nazi Germany and enhanced by apartheid-era South Africa to get around fuel embargoes. Japan, the US and several other nations also launched small-scale trials after the oil price shock of the early 1970s. Most experiments were abandoned due to environmental and cost concerns. China has launched two major coal-to-liquid projects. One, in Ningxia, is a tie-up with SASOL that uses the South African firm's gasification methods. The other facility, in Ordos, Inner Mongolia, and run by Shenhua, pioneers a direct liquefaction technique that “cracks” carbon with hydrogen extracted from water to produce clear diesel. Shenhua hopes to expand production fivefold, largely using coal from the nearby Shangwan mine. The main driver is cost. Shu Geping, the chief engineer at the plant, says the price of liquid coal is competitive when the cost of oil is over $40 a barrel. In the future, as production increases and the technology is improved, it will become even cheaper.” [Source: Jonathan Watts, The Guardian, November 15, 2009]

On efforts to build a cheaper coal gasifer in China Evan Osnos wrote in The New Yorker, “A pair of engineers took me to see their laboratory: a drab eight-story concrete building, crammed with so many pipes and ducts that it felt like the engine room of a ship. We climbed the stairs to the fourth floor and stepped into a room with sacks of coal samples lining the walls like sandbags. In the center of the room was a device that looked like a household boiler, although it was three times the usual size, and pipes and wires bristled from the top and the sides. It was an experimental coal “gasifier,” which uses intense pressure and heat to turn coal dust into a gas that can be burned with less waste, rather than burning coal the old-fashioned way. With a coal gasifier, it is far easier to extract greenhouse emissions, so that they can be stored or reused, instead of floating into the atmosphere. Gasifiers have been around for decades, but they are expensive — from five hundred million to more than two billion dollars for the power-plant size — so hardly any American utilities use them. The researchers in Xi’an, however, set out to make one better and cheaper.” [Source: Evan Osnos, The New Yorker, December 21, 2009]

When Albert Lin, an American energy entrepreneur on the board of Future Fuels,, set out to find a gasifier for a pioneering new plant that is designed to spew less greenhouse gas, he figured that he would buy one from G.E. or Shell. Then his engineers tested the Xi’an version. It was “the absolute best we’ve seen,” Lin told me. (Lin said that the “secret sauce” in the Chinese design is a clever bit of engineering that recycles the heat created by the gasifier to convert yet more coal into gas.) His company licensed the Chinese design, marking one of the first instances of Chinese coal technology’s coming to America.

Environmental Concerns with Coal Diesel and Gas Liquification in China

On the environmental impact of coal-to-liquid technology in China Watts wrote: "Environmental concerns will weigh against economic benefits. On the surface, the plant is impressively clean. There is no smell and in the glow of an Inner Mongolian sunset, white and pink smoke billows from its pipes. But for each tonne of the liquid, six and a half tons of water must be piped from an aquifer more than 70 kilometers away and more than three tons of carbon dioxide are released into the air. These are major concerns for a country that is already desperately short of water and increasingly criticized as the world's biggest emitter of greenhouse gases.” [Source: Jonathan Watts, The Guardian, November 15, 2009]

“Government researchers have been cautious about adopting this technology nationwide because liquid coal results in 50 percent to 100 percent more emissions than a comparable amount of oil. The prospect of millions of petrol tanks being filled with such a fuel has alarmed environmentalist groups. “Developing this technology on a big scale will lock China up even further in its unsustainable reliance on coal, which is the biggest cause of climate change,” said Yang Ailun, of Greenpeace.” In 2008, the government blocked several new proposals for coal liquefaction facilities. But this may be to ensure the monopoly of the state firm.

“Shu insists his new facility can be good for the environment because it is equipped to capture and condense carbon dioxide for possible storage. Beijing's policymakers are doubtful. They believe dumping carbon underground is expensive and risky for local environments. But under foreign pressure, they have identified more than 100 sites for potential storage. Ordos will lead the way, but it remains to be seen whether its scientists will be as successful with carbon storage as they have been with coal liquefaction.”

Debate Over Coal Use and Climate Change in China

In March 2021, Chinese President Xi Jinping announced a plan, endorsed by China’s Communist Party-controlled legislature, to reduce China’s emissions of carbon dioxide, which would peak before 2030, he said, and reach net carbon neutrality before 2060, A key part of the plan was reducing coal use, which set off a fierce debat on the issue within China.

Chris Buckley wrote in the New York Times: “The China National Coal Association issued a report proposing modest increases in its use for the next five years, reaching 4.2 billion metric tons by 2025, and also said China should create three to five “globally competitive world-class coal enterprises.” “The principal status of coal in our national energy system, and its role as ballast, will not shift,” the association said in an earlier position paper. [Source: Chris Buckley, New York Times, March 16, 2021]

“Provincial governments have recently proposed more new coal mines and power plants, while vowing that their projects will limit emissions. In answer to the call for a carbon peak, Shanxi Province, one of China’s biggest coal producing areas, announced plans for 40 “green,” efficient coal mines. Chinese officials in such areas also worry about losses of jobs and investment and the resulting social strains. They argue that China still needs coal to provide a robust base of power to complement solar, wind and hydropower sources, which are more prone to fluctuating. And many energy companies backing these views are state-owned behemoths that have easy access to political leaders. “Local governments see coal power as a robust energy shield,” Lu Zhonglou, a Chinese businessman who sold his coal mines a few years ago and still keeps an eye on the industry, said in a telephone interview. “You can’t write off coal too early.”

“But proponents of China’s green transition, including government advisers, argue that rapidly abandoning fossil fuels and shifting from old-school heavy industry will benefit growth, innovation, health and the environment. Some say China can ramp up wind and solar sources and reach a carbon peak much earlier than 2030, which would lower the costs and technological hurdles of reaching carbon neutrality. “A lot of heavy lifting is being left for the time after 2030,” said Lauri Myllyvirta, who monitors Chinese climate and energy policies as the lead analyst at the Center for Research on Energy and Clean Air in Helsinki. “The central contradiction between expanding the smokestack economy and promoting green growth appears unresolved.”

Chinese icoal-fired power plants usually run at about half full capacity. In 2021, the Chinese government said it would help them run at full capacity, raising concerns about greenhouse gas emissions and Beijing's climate pledges. The move was seen to prevent crippling power shortages that occurred in 2021 from happening again. AFP reported: The focus on energy security and economic growth was reiterated at a high-level meeting of China's State Council, chaired by Premier Li Keqiang. It was decided at the meeting that "coal supply will be increased and coal-fired power plants will be supported in running at full capacity and generating more electricity" to meet industrial and residential demand, according to Xinhua. The move comes weeks after President Xi Jinping told top policymakers to ensure that emissions reductions do not hurt economic growth and energy security — widely seen as a signal to limit restrictions on the coal sector. "We are pivoting back to the model of supporting the economy at all costs," said Li Shuo, a campaigner for Greenpeace China. [Source: AFP, February 16, 2022]

China’s Export of Coal-Fired Plant Technology

Internationally, China promotes and invest in a range of coal project in direct contradiction to pledge to reduce climate change gases. According to AFP: Globally, coal use accounts for 40 percent of emissions of carbon dioxide and began rising in 2017 after declining slightly from 2014 to 2016. More than two-fifths of the world’s electricity is generated by coal-fired power — nearly double the share of natural gas, and 15 times more than solar and wind combined. A quarter of coal plants in the planning stage or under construction outside China are backed by Chinese state-owned financial institutions and corporations, according to research by IEEFA, an energy finance think-tank based in Cleveland, Ohio. “Remove India from the picture, and the share of coal development supported by China rises to above a third.[Source: AFP-JIJI Japan Times, December 6, 2018]

“In Vietnam, Bangladesh and the Philippines, electricity generation shot up more than 20 percent from 2014 to 2017 — triple the global average — with China-backed coal powering a significant part of the increase.“Many of the recipients of China’s largesse — Egypt, Nigeria, Kenya, Senegal, Zimbabwe and half a dozen others — currently have little or no coal-fired power, and no coal to fuel future plants. “That means they will have to build import infrastructure, or even coal mines,” said said Christine Shearer, an energy analyst for CoalSwarm. Chinese banks and investment agencies have committed more than $21 billion to developing 31 gigawatts of coal-fired capacity in a dozen countries, and an additional $15 billion is on offer to support projects that would generate 71 GW in 24 nations, for a total of more than 101 GW, IEEFA found.

“Worldwide, there are nearly 2,500 coal-fired stations of 30 megawatts or larger in operation, with a combined capacity of about 2,000 GW, according to the Global Coal Plant Tracker. “A glut of new coal infrastructure would bury our chances of keeping global warming well below 2 C,” said Heffa Schuecking, director of Urgewald, an environmental NGO based in Germany that tracks the coal sector. “The Chinese government needs to stop bankrolling new coal plants both at home and abroad.” Any pathway to a 1.5-C world — even one that allows for “overshooting” the target and depends heavily on extracting carbon dioxide from the air — requires the near elimination of coal from the energy mix by midcentury, according to the U.N.

“China is not alone in peddling the most carbon-intensive of fossil fuels beyond its borders. As of last month, South Korea and its export credit agencies were positioned to back 12 GW of coal-fired power abroad, and Japan was behind another 10, according to a research note from Han Chen, international energy policy manager at the Natural Resources Defense Council. During the 2013-2018 period, South Korea and Japan financed 8 GW and 20 GW, respectively. But their shares were dwarfed by China’s, whose financing covered as much power generation as Japan and South Korea combined. The three East Asian rivals supported 90 percent of the 135 GW built since 2013 or in the pipeline.

Image Sources: Westport Schools; BBC; Environmental News; Tropical Island

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated June 2022