CHINESE SOCIETY AND COMMUNISM

In China the authority of the state and maintenance of social stability have precedence over the well being of individuals and individual rights. Chinese are taught in the education system and often told by their parents to devote their energies and talents for the good of China not for their personal glory or money.

In China the authority of the state and maintenance of social stability have precedence over the well being of individuals and individual rights. Chinese are taught in the education system and often told by their parents to devote their energies and talents for the good of China not for their personal glory or money.

Communist society has not been a classless society. Under Mao, it was essentially divided into three tiers: 1) the privileged elite that ran the country; 2) the urban, educated professional class; and 3) the blue-collar industrial workers and farmers. The most basic social divisions were between the peasants, mostly subsistence farmers bound to the land, and urban people who worked in factories and in the bureaucracy

The government has the ability to mobilize large numbers of people quickly. The military is called in to help offer relief after major earthquakes or floods. Neighborhood watch teams make sure parents don’t have too many children and keep an eye out for terrorists.

There is an understanding in China that you can do most anything, say anything and wear anything as long as you stay out of politics and don’t try to organize people. Chinese that have overstepped the bounds have ended up in jail or had to sit through self-criticism meetings and admit faults they really didn't have.

Jane Macartney wrote in the Times of London that a prevailing, underlying fear pervades the system in China: “Fear of trouble, fear of reprisals, fear of fines, fear of a blot on your records, fear of consequences, often vague and undefined.”

Good Websites and Sources: Book: Civil Discourse, Civil Society and Chinese Communities by Randy Kluver, John Powers/books.google.com ; Book: Studies in Chinese Society by Arthur Wolfe, Emily Ahern, Emily Martin/books.google.com ; Wikipedia article Wikipedia ; Library of Congress loc.gov/cgi-bin ; Sources on Chinese Society newton.uor.edu ; Mao on Classes in Chinese Society marxists.org ; Disparity of Income bbc.co.uk ; Chinatown Connection chinatownconnection.com ;

Links in this Website: CHINESE SOCIETY, CONFUCIANISM, CROWDS AND VILLAGES Factsanddetails.com/China ; CHINESE SOCIETY AND COMMUNISM Factsanddetails.com/China ; CHINESE PEOPLE Factsanddetails.com/China ; CHINESE PERSONALITY AND CHARACTER Factsanddetails.com/China ; CHINESE PERSONALITY TRAITS AND CHARACTERISTICS Factsanddetails.com/China ; REGIONAL DIFFERENCES IN CHINA Factsanddetails.com/China ; FAMILIES, MEN AND YOUNG ADULTS Factsanddetails.com/China ; RELIGION, FOLK BELIEFS AND DEATH ( Main Page, Click Religion) Factsanddetails.com/China

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: "Why China Leads the World: Talent at the Top, Data in the Middle, Democracy at the Bottom" by Godfree Roberts Amazon.com; "From the Soil: The Foundations of Chinese Society" by Xiaotong Fei , Gary G. Hamilton, et al. Amazon.com; “China in Ten Words” by Yu Hua, translated from the Chinese by Allan H. Barr (Pantheon) Amazon.com; “The Individualization of Chinese Society” by Yunxiang Yan Amazon.com; “Religion in Chinese Society: A Study of Contemporary Social Functions of Religion and Some of Their Historical Factors” by C.K. Yang Amazon.com; “Gods, Ghosts, and Gangsters: Ritual Violence, Martial Arts, and Masculinity on the Margins of Chinese Society” by Avron Boretz Amazon.com; “Understanding Chinese Society” by Xiaowei Zang Amazon.com; “Understanding Chinese Society: Changes and Transformations” by Eileen Yuk-ha Tsang Amazon.com; “Chinese Society in the Eighteenth Century” by Susan Naquin and Evelyn S. Rawski Amazon.com; “A History of Chinese Civilization” by Jacques Gernet Amazon.com

Chinese Society in the Mao Era

After the establishment of the People's Republic in 1949, the uncertainty and risks facing small-scale socioeconomic units were replaced by an increase in the scale of organization and bureaucratization, with a consequent increase in predictability and personal security. The tens of millions of small enterprises were replaced by a much smaller number of larger enterprises, which were organized in a bureaucratic and hierarchical manner. Collectivization of land and nationalization of most private businesses meant that families no longer had estates to pass along. Long-term interests for families resided primarily with the work unit (collective farm, office, or factory) to which they belonged. [Source: Library of Congress]

“Mobility in most cases consisted of gaining administrative promotions within such work units. Many of the alternate routes to social mobility were closed off, and formal education continued to be the primary avenue of upward mobility. In villages the army offered the only reasonable alternative to a lifetime spent in the fields, and demobilized soldiers staffed much of the local administrative structure in rural areas. For the first time in Chinese history, the peasant masses were brought into direct contact with the national government and the ruling party, and national-level politics came to have a direct impact on the lives of ordinary people. The formerly local, small-scale, and fragmented power structure was replaced by a national and well-integrated structure, operating by bureaucratic norms. The unpredictable consequences of market forces were replaced by administrative allocation and changing economic policies enforced by the government bureaucracy.

“The principal transformation of society took place during the 1950s in a series of major campaigns carried out by the party. In the countryside, an initial land reform redistributed some land from those families with an excess to those with none. This was quickly followed by a series of reforms that increased the scale of organization, from seasonal mutual aid teams (groups of joint support laborers from individual farming households), to permanent mutual aid teams, to voluntary agricultural cooperatives, to compulsory agricultural cooperatives, and finally to large people's communes. In each step, which came at roughly two-year intervals, the size of the unit was increased, and the role of inherited land or private ownership was decreased. By the early 1960s, an estimated 90 million family farms had been replaced by about 74,000 communes. During the same period, local governments took over commerce, and private traders, shops, and markets were replaced by supply and marketing cooperatives and the commercial bureaus of local government. In the cities, large industries were nationalized and craft enterprises were organized into large-scale cooperatives that became branches of local government. Many small shops and restaurants were closed down, and those that remained were under municipal management.

“In both city and countryside, the 1950s saw a major expansion of the party and state bureaucracies, and many young people with relatively scarce secondary or college educations found secure white-collar jobs in the new organizations. The old society's set of formal associations — everything from lineages (clans), to irrigation cooperatives, to urban guilds and associations of persons from the same place of origin, all of which were private, small-scale, and usually devoted to a single purpose — were closed down. They were replaced by government bureaus or state-sponsored mass associations, and their parochial leaders were replaced by party members. The new institutions were run by party members and served as channels of information, communication, and political influence.

Social Differentiation in Maoist China

Work units (danwei) belong to the state or to collectives. State-owned units, typically administrative offices, research institutes, and large factories, offer lifetime security, stable salaries, and benefits that include pensions and free health care. Collectives include the entire agricultural sector and many small-scale factories, repair shops, and village- or township-run factories, workshops, or service enterprises. Employees on the state payroll enjoy the best benefits modern China has to offer. The incomes of those in the collective sector are usually lower and depend on the performance of the enterprise. They generally lack health benefits or pensions, and the collective units usually do not provide housing or child-care facilities. In 1981 collective enterprises employed about 40 percent of the nonagricultural labor force, and most of the growth of employment since 1980 has come in this sector. Even though the growth since 1980 of individual businesses and small private enterprises, such as restaurants and repair services, has provided some individuals with substantial cash incomes, employment in the state sector remains most people's first choice. This reflects the public's recognition of that sector's superior material benefits as well as the traditional high prestige of government service.

Work units (danwei) belong to the state or to collectives. State-owned units, typically administrative offices, research institutes, and large factories, offer lifetime security, stable salaries, and benefits that include pensions and free health care. Collectives include the entire agricultural sector and many small-scale factories, repair shops, and village- or township-run factories, workshops, or service enterprises. Employees on the state payroll enjoy the best benefits modern China has to offer. The incomes of those in the collective sector are usually lower and depend on the performance of the enterprise. They generally lack health benefits or pensions, and the collective units usually do not provide housing or child-care facilities. In 1981 collective enterprises employed about 40 percent of the nonagricultural labor force, and most of the growth of employment since 1980 has come in this sector. Even though the growth since 1980 of individual businesses and small private enterprises, such as restaurants and repair services, has provided some individuals with substantial cash incomes, employment in the state sector remains most people's first choice. This reflects the public's recognition of that sector's superior material benefits as well as the traditional high prestige of government service.

‘security and equality" have been high priorities in modern China and have usually been offered within single work units. Because there is no nationwide insurance or social security system and because the income of work units varies, the actual level of benefits and the degree of equality (of incomes, housing, or opportunities for advancement) depend on the particular work unit with which individuals are affiliated. Work units are responsible for chronic invalids or old people without families, as well as for families confronted with the severe illness or injury of the breadwinner. Equality has always been sought within work units (so that all factory workers, for example, received the same basic wage, or members of a collective farm the same share of the harvest), and distinctions among units have not been publicly acknowledged. During the Cultural Revolution, however, great stress was placed on equality in an abstract or general sense and on its symbolic acting out. Administrators and intellectuals were compelled to do manual labor, and the uneducated and unskilled were held up as examples of revolutionary virtue.

“In the mid-1980s many people on the lower fringes of administration were not on the state payroll, and it was at this broad, lower level that the distinction between government employees and nongovernment workers assumed the greatest importance. In the countryside, village heads were collectivesector workers, as were the teachers in village primary schools, while workers for township governments (and for all levels above them) and teachers in middle schools and universities were state employees. In the armed forces, the rank and file who served a three- to five-year enlistment at very low pay were considered citizens serving their military obligation rather than state employees. Officers, however, were state employees, and that distinction was far more significant than their rank. The distinction between state and collective-sector employment was one of the first things considered when people tried to find jobs for their children or a suitable marriage partner.

Security, Lack of Responsibility and Going Through the Motions

Maoist rule fostered a widespread culture of dependency. People had few worries and made few decisions and rarely had to fend for themselves because the government took care of everything for them: housing, education, employment, material goods and even mates. Marriages were often arranged by work committees. People didn’t have to look for jobs themselves. Today, many people feel shocked and betrayed by the way things they were entitled to under Mao system have been taken away. See Welfare, Government

Everything was guaranteed in the Maoist system. Everyone had a job and access to social services, child care, adult education and even lunch. One woman told National Geographic, "We had our jobs, a home, and food. What bothered us was being shut in and not being able to speak our minds freely.”

The government regulated everything from the content of newspapers to the production of toothpaste and made almost all economic decisions. Some people went through their whole lives without having to make a major decision about the lives or their future. "In the old days everything was decided for us," one man told the Washington Post. "It was easy because we did not have to choose. Now we find we have make decisions on our own; and freedom of opinion brings along a lot more responsibility."

"You learn at an early age," one man told National Geographic, "that in many instances absolutely nobody believes what the government is saying. At a political meeting a party member will talk. He'll know what he's saying is nonsense. And he'll know that you know."

Equal in Poverty and Social Obligations in China

In the old days Chinese were indoctrinated to believe they were better off than people elsewhere in the world and they believed this because there was little evidence to contradict it because Chinese had little exposure to the outside world through the media.

Nobel Prize winning poet Joseph Brodsky described life in the Communist era as "equal in poverty". There the was no private property, inherited wealth, or great income disparities.

One intellectual told National Geographic, "There was a uniformity to life. Everyone was more or less equal. Everyone lived more or less OK, or equally badly, but no one was rich. Everyone dreamed about freedom, and this united them. People could recognize each other, who they were, with just a couple of words. This created a certain ambiance, a quality of human relations. It wasn't wonderful, but it was familiar."

Even today many would rather see everyone poor than see a few lucky rich ones who make everyone else jealous.* Alessandra Stanley wrote in the New York Times, "There was no shame in poverty when only criminals and party officials were rich. Obscurity was noble when professional achievement was bound up with political compromise.

Life was also shaped by social obligations. Many people have bad memories of working for voluntary work patrols in which they were forced to participate. Students and soldiers helped in harvest. In some places, one day every year people helped sweep up the city for no money.

Opportunities and Competition in China

In China there is a cultural pattern stressing individual achievement and upward mobility. These are best attained through formal education and are bound up with the mutual expectations and obligations of parents and children. There is also a social structure in which a single, bureaucratic framework defines desirable positions, that is, managerial or professional jobs in the state sector or secure jobs in state factories. [Library of Congress]

“In the Mao era banned migration, lifetime employment, egalitarian wage structures, and the insular nature of work units were intended by the state, at least in part, to curtail individual competition. Nevertheless, some jobs are still seen as preferable to others, and it is urbanites and their children who have the greatest opportunities to compete for scarce jobs. The question for most families is how individuals are selected and allocated to those positions. The lifetime tenure of most jobs and the firm control of job allocation by the party make these central issues for parents in the favored groups and for local authorities and party organizations.

“In the early and mid-1950s, the problem was not acute. State offices were expanding rapidly, and there were more positions than people qualified to fill them. Peasants moved into cities and found employment in the expanding industrial sector. Attempts to manage the competition for secure jobs were among the many causes of the radical, utopian policies of the period from 1962 to 1976. Among these, the administrative barriers erected between cities and countryside and the confinement of peasants and their children to their villages served to diminish competition and perhaps to lower unrealistic expectations. Wage freezes and the rationing of both staples and scarce consumer goods in cities attempted to diminish stratification and hence competition.

“Tensions were most acute within the education system, which served, as it does in most societies, to sort children and select those who would go on to managerial and professional jobs. It was for this reason that the Cultural Revolution focused so negatively on the education system. Because of the rising competition in the schools and for the jobs to which schooling could lead, it became increasingly evident that those who did best in school were the children of the "bourgeoisie" and urban professional groups rather than the children of workers and peasants. The Maoist policies on education and job assignment were successful in preventing a great many urban "bourgeois" parents from passing their favored social status on to their children. This reform, however, came at great cost to the economy and to the prestige and authority of the party itself.

Neighborhood Committees in China

On a local level the Communist Party bureaucracy has been made up of millions of neighborhood committees which have to answer to the next level up, the street or village committees. In the cities, several street committees make up a district committee which in turn are under the jurisdiction of the Municipal People's government or the Regional People's government. All of these committees follow guidelines laid out by the national government. To keep their members in line, the local committees often use social pressure in the form of face-losing criticism.

On a local level the Communist Party bureaucracy has been made up of millions of neighborhood committees which have to answer to the next level up, the street or village committees. In the cities, several street committees make up a district committee which in turn are under the jurisdiction of the Municipal People's government or the Regional People's government. All of these committees follow guidelines laid out by the national government. To keep their members in line, the local committees often use social pressure in the form of face-losing criticism.

Neighborhood committees in urban areas have made sure the poor are fed, the elderly are looked after, petty crimes are brought to justice, one-child polices are adhered to, and family disputes — mostly between wives and mothers-in-laws — are settled. For the most part the streets in cities are safe. Some residents feel so safe they bring their beds outdoors in the summer.

A typical neighborhood committee controls three blocks and contains about 1,000 households. The leader and his or 30 or so "group leaders" are in charge of hanging party propaganda posters, leading weekly meetings of the local party cell, where new polices and rules are announced. Retired women often hold the job. They are sometimes called "bound feet detectives" because of their shuffling feet and busybody attitude. [Source: Wall Street Journal]

Neighborhoods are kept in line with “building bosses” and their helpers, “door watchers,” who keep an eye on what is going on in almost every house. Informers are everywhere. Communist-era proverb: "One Chinese watches a thousand; a thousand Chinese watch one."

Work Units in China

Most Chinese also have had to answer to "community units" or "work units" (“dawei”) in their place of work, whether it be a factory, hospital, commune or public works project. In the old days, these organizations exerted control on almost every aspect of an individual's life: they gave out ration cards, arranged day care, supplied train tickets, chose which doctors and hospitals people wented to, decided who gets housing, set salaries and recruited party members. The lives of some people are still controlled by work units but not as many as before.

Work units have been the main channels in Communist China for distributing social benefits and exerting social control. Even today they keep files on their members and often have to be consulted about personal matters such as travel or children, and are able to pressure people by reducing wages and bonuses, by denying promotions and transfers, or by taking away the job completely.

In the old days, work units and neighborhood committees controlled marriages, divorces, pregnancies and birth control. To get married, a couple needed permission from a local board and a letter from an employer stating that a person was single. In some cases, employers would use their authority to solicit a bribe or demand some concession before the form was submitted. In most cases the employers provided the paper work but the couples felt inconvenienced and embarrassed asking for permission.

In the Mao era, people lived in assigned housing in state dormitories, communes and factory quarters and bought food and clothing with rationed coupons.

Decline of Neighborhood Committees and Work Units

Chinese society demands much less conformity in political views and personal lifestyles than it used to, especially in the Mao era. One of thee biggest changes had been the gradual erosion of the population registration system, which tied people to their places of birth, preventing internal migration and even tourism.

Chinese society demands much less conformity in political views and personal lifestyles than it used to, especially in the Mao era. One of thee biggest changes had been the gradual erosion of the population registration system, which tied people to their places of birth, preventing internal migration and even tourism.

Neighborhood committees and work units no longer exert the control on people's lives they once did. Their powers began to diminish in the 1980s in rural areas with the rapid collapse of communes and the giving of land and decision-making power to farmers. Work units began collapsing in the cities in the 1990s as state-owned industries began going bankrupt or were shut down or restructured.

There are still an estimated 500,000 neighborhood committee cadres. The leaders are paid around $250 a month. These days their duties include helping the unemployed find jobs, organizing anti-crime efforts, keeping track of childbearing women, and helping married couples stay together. From time to time, the leaders are called on to do things like count Falun Gong members.

There is now some discussion about making the neighborhood committees small welfare agencies and hiring college graduates instead of retired women.

See State White-Collar Workers in the Mid-2000s, Labor, Economics

Spiritual Civilization in China

In the late 1990s, the government under Jiang Zemin launched a “spiritual Civilization” campaign in which people were encouraged to be more cultured and shed their bad habits. Described by Steven Mufson in the Washington Post as "one part Leninist ideology, one part Miss Manners," it covered everything from spiting in public to reuniting the motherland and advised people to pay their taxes, avoid too much raw or cold foods, take frequent showers, cut one’s fingernails and perform good deeds.

As part the campaign the airwaves were filled with moralizing lectures; billboards listed the "Nine Commandments" beginning with "Love Your Country"; husbands were told to help around the house; and children were told cook "soft and mushy" meals for their elders. Some places even banned swearing and impolite behavior and created "civilized citizen" pledges.

Shanghai launched a "Seven Nos" campaign (no spitting, no jaywalking, no cursing, no destruction of greenery, no vandalism, no littering and no smoking). An effort was also made to clean up the city's public toilets. Businessmen encouraged their employees not to use phrases such as "Don't have it," "Can't you see I'm busy," and "Hurry up and pay."

In Dalian, citizens were promised cash rewards for reporting rude taxi drivers; travelers were fined for spitting; scavengers were banned from bagging doves and pigeons in the central squares; and soccer fans were told to tone down their insults of players on opposing teams.

As part of the "One Million Party Members Care" campaign a hotline was set up in Beijing for complaints of sloppy house repairs, sanitation problems, shoddy goods and problems with urban life.

Model Towns and Model Citizens in China

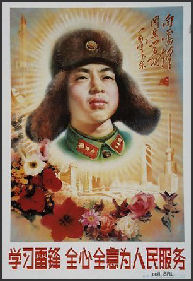

Lei Feng. Model Citizen

In the “spiritual civilization” campaign the government set up of model towns filled with placards that read: “Follow Regulations,” “Love Your Country, Love Your City,” and “Be a Model Citizen.” The citizens were expected to attend twice-weekly ideology classes in which people were informed about “clean” and “dirty” habits. Those who were caught gambling, arguing with neighbors or failing to put their garbage in the proper plastic bag were required to wear yellow vests that advertised their shame. Households that followed all the rules were rewarded with tax exemptions and plaques on their houses that stated they were a “New Wind Family.”

The "spiritual civilization" campaign also honored "everyday heros” and “model citizens” such as Xu Hu, a Shanghai plumber who fixed leaky toilets for free; Li Guon, a well-driller who helped poor villages in the Gobi Desert find water; and Li Suli, a bus conductor who arrived early to work to wash her bus and charmed passengers with her smiles and friendly advice. Other model citizens included a cancer patient who got out of bed the day after an operation an swept all the floors in the hospital, and a bank manager who helped monks at a temple load 10 tons of coins on a truck and take it a bank where the monks opening a high-interest account.

Jiang also stressed “guoqing” ("Chinese-ness) and launched a "Three Stresses" campaign: highlighting a need for theoretical study, political awareness and good conduct. The program was criticized as a waist of time and energy.

Harmonious Society and the Eight Virtues and Eight Shames

Hu Jintao made “building a harmonious society” — a reference to spreading the wealth from the haves to have nots and correcting the injustices of Chinese society and combating widespread corruption — a top priority. How serious and successful he is has not yet been determined. In the hinterlands the Communist Party has done little to respond to injustices (See Protests and Demonstrations, Government).

Speeches by party leaders emphasize unity and harmony but in society there is more individuality and personal freedom because people have more money and more options than they used to.

Hu has promoted the idea that the solutions to China’s problems lie in a return to Marxist and Mao ideology and Confucian values, and sees Chinese culture as providing it own moral direction, with perhaps a storng dose of nationalism thrown in for good measure. A line from the song that has accompanied the harmonious society campaign goes: “It’s most glorious to love the motherland, a great sin to harm her.”

Many are not exactly sure what all this means but some think it is a green light to some forms of dissent that allow citizens to let off steam. The Hu government has held public hearings on some controversial matters, allowed more freedom of the press and expression on the Internet and refused to wield a heavy hand when protests break out in part to let people vent their frustrations while the government maintains a firm grip on power.

In step with his plan to make China a more harmonious place and combat greed and corruption. Hu issued “Eight Virtues and Eight Shames”: 1) Love the motherland, do not harm it; 2) Serve don’t deserve people; 3) Uphold science, don’t be ignorant and unenlightened; 4) Work hard, don’t be lazy; 5) Be united and help each other, don’t benefit at the expense of others; 6) Be honest, not profit-mongering; 7) Be disciplined and law-abiding, not chaotic and lawless; 8) Know plain living and hard struggle, do not wallow in luxuries.” The message has been placed on billboards, featured on the front pages of newspapers and repeated over and over on television and radio.

China’s Issues Higher 'Moral Quality' for its Citizens

In October 2019, in conjunction with secretive conclave of high-ranking officials in Beijing to discuss China’s future direction, China's Communist Party issued a set guidelines to its citizens to improve their "moral quality" included instructions on dressing appropriately, avoiding online pornography and how much to spend on a rural weddings. AFP reported: “The government published its "Outline for the Implementation of Citizen Moral Construction in the New Era" — which advises readers how to use the internet, raise children, celebrate public holidays and behave while travelling abroad. The guidelines from the Central Commission for Guiding Cultural and Ethical Progress calls for building "Chinese spirit, Chinese values, and Chinese power". [Source: AFP, October 30, 2019]

“The texts urge citizens to avoid pornography and vulgarity online, and follow correct etiquette when raising the flag or singing the national anthem. Public institutions like libraries and youth centres must carry out "targeted moral education" to improve people's ideological awareness and moral standards, according to the rules. The guideline also stresses patriotism and loyalty to the motherland. "People who have a servile attitude to foreign countries, damage national dignity and sell national interests must be disciplined according to the law," it says.

A separate set of behavioural guidelines published this week targeted China's rural areas, and urged local governments to weed out "bad customs". These included abuse of the elderly as well as the practice of extravagant weddings and funerals, according to Zhang Zhiyong, an official from the commission. Zhang said the most important thing for "rural civility" is the construction and improvement of ideology and morality. "We must strengthen marital education for young people, and put to full use the Communist Youth League, women's federations, and other group organisations," said Zhang.

“State broadcaster CCTV said that the custom to spend a lot on weddings and provide a house and gifts for a new bride — often beyond the means or poorer rural families — was "putting pressure on unmarried males". “China's decades-long one-child policy has resulted in a massive gender gap, and Beijing is anxious about the potential social impact of millions of unmarried men in the countryside. Zhang called for official organisations to be more closely involved in the lives of rural villagers.

“The rules were published as Beijing holds The Fourth Plenum of the Party's Central Committee, a closed-door meeting of high-ranking officials where the country's roadmap and future direction is discussed. Beijing produced a list of 58 national "moral models" who exemplify patriotism and "lofty morality" for the celebration of China's 70th national holiday on October 1. The latest round of moral guidelines update an earlier set published in 2001. "Money-worship, hedonism, and extreme individualism have grown," according to the 2001 guidelines. Eighteen years later, the refreshed guidelines listed the same offences — and described them as "still outstanding".

Twelve Core Socialist Values Songs and Dances

The Chinese Communist Party’s 12 "core socialist values" was divided into three hierarchically-organized categories: nation, society, citizen. Written using 24 Chinese characters and enshrined in 2012 at the 18th Communist Party Congress, the 12 are freedom, equality, patriotism, dedication, prosperity, democracy, civility, harmony, justice, rule of law, integrity and friendship. “At a high-level meeting in early 2014, President Xi Jinping called on officials to take every opportunity to propagate the core socialist values in culture, education and other aspects of society. “Make them all-pervasive, just like the air,” he said. Critics scoff at the inclusion of democracy, freedom and rule of law on the list.

After four of the values were set to songs and dances, Kiki Zhao wrote in the New York Times’s Sinosphere: “The 12 “core socialist values” are memorized by schoolchildren, featured in college entrance exams, printed on stamps and lanterns, and splashed on walls across China. Now they have made their way into 20 song-and-dance routines that the authorities in Hunan Province plan to promote to the country’s millions of “square dancers,” the mostly middle-aged and older women who gather in public squares to perform in unison. At a news conference kicking off the campaign a dozen women in white pants and yellow tunics bounced and twirled to the lyrics of one of the songs: “Freedom, equality, helping one another! Patriotism, dedication, everyone loves it!” “This is to spread our core socialist values in a way that the public loves to see and hear,” said Li Hui, director of the Hunan Culture Department, according to local television. “In this happy melody, the 24 characters are memorized.” [Source: Kiki Zhao, Sinosphere, New York Times, September 1, 2016]

“The department has trained 15,000 teachers who will instruct people in schools, factories, businesses and both urban and rural communities on how to perform the routines, collectively titled “Let’s All Dance.” The Hunan authorities also plan to invite teachers from other provinces to learn the dances. Tang Zuobin, an official at the Hunan Culture Department, said in a telephone interview on Thursday that the province was preparing 10,000 textbooks accompanied with videos of the dances for distribution across China. He said the department had undertaken the project under the direction of the Ministry of Culture.

“Mr. Tang said that the popularity of square dancing made it an ideal vehicle for the propagation of the core socialist values. In Hunan, he said: “As long as there’s a square, there are square dances. Lots of people participate in square dances, and we want to give them more opportunities to dance.” Lei Tao, manager of the Hunan Dama Club (“dama” means “aunties”), said in an interview that his group, which has about 20,000 members, overwhelmingly women ages 45 to 70, had heard about the project and planned to start practicing the routines soon.

“But not everyone in China has embraced the idea of either square dancing or the core socialist values. There have long been complaints in China about square-dance music blaring near people’s homes. In 2014, residents in Wenzhou, in Zhejiang Province, bought their own sound system to broadcast warnings to square dancers about violating noise pollution laws. “It’s so tiring to be a Chinese, when a dance has to demonstrate core socialist values,” a person going by the name of Shanapu wrote on Weibo. “Do we need to demonstrate these when we go to the toilet, too?” Many other online commenters have mocked the routines as a form of “loyalty dance,” performed during the Cultural Revolution to show fealty to Mao Zedong.” “Let’s sing. Let’s jump,” go the lyrics to one the songs. “We all enjoy prosperity and democracy! This is a good time with justice and the rule of law!”

Beijing’s Harmonious Families Award Becomes More Materialistic

In February 2012, All-China Women's Federation” the city’s oldest, and most important, women’s organization in China, said that to be eligible for their new "Capital Harmonious Family" award, a family living in Beijing should own a library of at least 300 books, have an Internet connection and subscribe to at least one newspaper. It also said it was good if the family traveled frequently, ate out regularly and practiced a low-carbon lifestyle. Adam Minter of Bloomberg wrote:It was an elitist turn for an organization that was established in March 1949 to support the Communist Party, the rights and equality of women, and strong families. In the Confucian tradition, harmony in the home is considered a prerequisite to achieving harmony in society. So, in the early 1950s, the ACWF established the “Five Good Families” award for model families that exhibited five virtues, such as “marital harmony” and unwavering support of the party.[Source: Adam Minter, Bloomberg News, February 9, 2012]

In 2007, the Beijing branch of the ACWF renamed the honor the Capital Harmonious Family award to comply with President Hu Jintao’s comprehensive vision for building a harmonious society that promotes economic and social equality. It has been a popular, even iconic competition; the thousands of families who have won it enjoy more prestige and respect from their neighbors. Over the decades, the criteria for winning the award have changed to reflect both the party’s objectives and the tenor of the times. In 1986, when China was in the early flush of its economic reform, families that sought the award had to “be good at daring to reform ." When China was trying to enforce its “one child” population-control policies, the criteria changed to include “be good at family planning.”

“For a population that has become acclimated to thinking of its model families as paragons of personal and civic virtue, hearing them now defined in unambiguously material terms set off tempers. “They are selecting families that enjoy life among the upper and corrupt classes,” wrote Little Loach, the handle of a user on Tencent Weibo, China’s second-most popular microblog. “Not harmonious families.” Han Xiao, another Tencent Weibo user, wrote a more affecting response: “While those who struggle at the bottom of society worry about their livelihoods, or are busy paying the medical bills of the old and the cost of raising children, people with excellent living conditions are showing off that they can surf the Internet — through so-called competitions.” A poll on Sina Weibo, China's most popular microblog, recorded that 81 percent of the respondents rejected the new criteria entirely.

Despite tremendous economic gains over the past 30 years, few Beijing families can afford the cosmopolitan lifestyle the ACWF outlined. Party officials, however, are often perceived as affluent, living beyond the means of those not in, or connected to, government. Li Xu, a Tencent user, expressed the sentiment of many Chinese microbloggers when he wrote: “Everyone, and even every family, has a singular definition of happiness. After all, harmony, in its true state, is a natural thing. Why should it be limited by criteria? Don’t encourage society to despise the poor and curry favor with the rich.

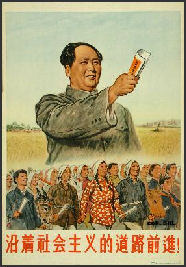

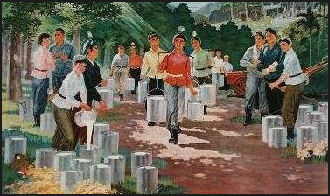

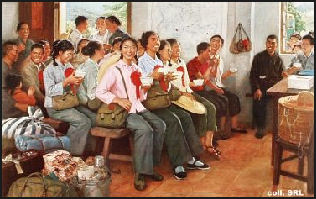

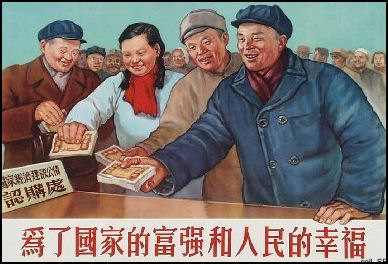

Image Sources: Posters, Landsberger Posters http://www.iisg.nl/~landsberger/. Photo: Cgstock http://www.cgstock.com/china

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated September 2021