WA ETHNIC GROUP

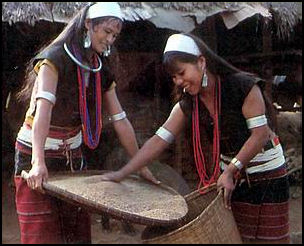

Wa villager in tradtional clothes

The Wa are a mountain people that live near the border of Chin and Myanmar in southwest Yunnan Province of China and the Shan State Myanmar. They live in a well defined homeland called A Wa Shan, in the southern part of the Nu Shan Mountains between the Mekong River (Lancang Liang) and the Salween River (Nu Liang). The Wa call themselves the Va, Pa rauk, and A va’all of which mean “a people who reside in the mountain.” Wa “means “people of the cave,” a reference to their legendary place of origin.

The Wa are also widely known as the Va as well as the Avo, Benren, Da ka va, Ka va, La, Le va, Pa rauk, Xiao ka va, Awa, Kawa, Lawa and Lua. They call themselves "Wa", "Baraoke", "Buraoke", "Awa", "Awo", "Awalai", "Lewa". Others call them "La", "Ben people", "Awa", "Kawa". They were called "Hala", "Hawa", and "Kawa" in history, which means "people living in mountains". The name "Wa" was fixed by the Chinese government in 1962. Most Wa in China live in the two Wa Autonomous counties of Ximen and Cangyuan in the Ava Mountains in western Yunnan Province. Most Wa in Myanmar reside in the Wa Hills in northeast Myanmar across the border from China's Yunnan province. [Source: Wang Aihe,“Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 6: Russia-Eurasia/China” edited by Paul Friedrich and Norma Diamond, 1994]

The Wa are known for their animal sacrifice ceremonies, their handwoven clothes and unique cooking methods. They hunted heads until a few decades ago and sometimes placed the heads of their victims in their rice fields as offerings to their rice god. They speak a Southeast Asian Mon-Khmer language that is similar to the language spoken by the De’angs and Bulang, small ethnic groups in Yunnan in China, but different from the Tibetan-Burman languages spoken by most of the southern Chinese ethnic groups.

The Wa had no written language until the Communist government gave them one after 1949. The still do not have a script for their own language. Some Wa keep records by cutting notches in sticks and convey messages by showing different objects. A chicken feather for example expresses urgency. Bananas, sugarcane and salt are offered to visitors as an expression of friendliness.

See Separate Articles: WA LIFE AND SOCIETY factsanddetails.com ; WA STATE AND THE UNITED WA STATE ARMY factsanddetails.com ; WA ETHNIC GROUP AND ILLEGAL DRUGS factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: “Stories from an Ancient Land: Perspectives on Wa History and Culture” by Magnus Fiskesjö (Berghahn, 2021), about Wa cosmology, xenology and sociality, and about fieldwork and participant intoxication; Amazon.com; “Maternal Souls Amidst Wooden Drum: The Was” by Wen Yiqun (Yunnan education publishing house,china, 1995) Amazon.com; “Peoples of the Greater Mekong: the Ethnic Minorities” by Jim Goodman and Jaffee Yeow Fei Yee Amazon.com ; “The Yunnan Ethnic Groups and Their Cultures” by Yunnan University International Exchange Series Amazon.com; “Writing with Thread Traditional Textiles of Southwest Chinese Minorities” by University of Hawaii Art Gallery Amazon.com “Ethnic Oral History Materials in Yunnan” by Zidan Chen Amazon.com; Separatism: “The United Wa State Party: Narco-Army or Ethnic Nationalist Party?” by Tom Kramer Amazon.com; “The Wa of Myanmar and China's Quest for Global Dominance” by Bertil Lintner Amazon.com; “Winning by Process: The State and Neutralization of Ethnic Minorities in Myanmar” by Jacques Bertrand, Alexandre Pelletier, et a Amazon.com; “Frontier Ethnic Minorities and the Making of the Modern Union of Myanmar: The Origin of State-Building and Ethnonationalism” by Zhu Xianghu Amazon.com; “Stalemate: Autonomy and Insurgency on the China-Myanmar Border” by Andrew Ong Amazon.com; “Rebel Politics: A Political Sociology of Armed Struggle in Myanmar's Borderlands” by David Brenner Amazon.com

Wa Region and Population

The total population of Wa is approximately 1.2 million, with A) 800,000 in Myanmar, nearly all of the in Shan State and Kachin State, in the northeastern part of the country; B) 400,000 in China, in western Yunnam Province: and C) around 10,000 in Thailand, mostly in the Chiang Rai area. The Wa have traditionally lived in the isolated mountain ranges in the border region between China and Myanmar. Most of their lands are poor. Capricious climatic conditions can produce floods and droughts. [Source: Wikipedia]

Historically, the Wa have inhabited the Wa States, a territory that they have claimed as their ancestral land since time immemorial. Situated is the southern part of the Nu Shan Mountains, between the Mekong and the Salween River, with the Nam Hka flowing across it, It is a rugged mountainous area with steep peaks that cut sharply through by numerous deep valleys with rivers and streams. The highest peak reaches 2,800 meters while the deepest valleys lie about 1,800 meters below that point. In the climate is subtropical and divided two seasons — a rainy one and a dry one — with annual average rainfall of 150 to 300 centimeters falling between June and October, and with an annual average temperature of 17° C, ranging from 0° to 35° C. [Source: Wang Aihe, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 6: Russia-Eurasia/China” edited by Paul Friedrich and Norma Diamond, 1994 ]

The Wa are one of the 135 officially recognized ethnic groups of Myanmar. One of the main ethnic groups in Shan State, they number around 800,000 (an estimate because no reliable censuses have been done in Myanmar, or at least made public) and make up only 0.16 percent of Myanmar’s total population and live mostly in small villages near Kengtung and north and northeastwards close to the Chinese border, as well as a small area east of Tachileik. The Wa Special Region 2 of the Northern Shan State or Wa State was formed by the United Wa State Army (UWSA) and the remains of the former Burmese Communist Party rebel group that collapsed in 1989. The UWSA more or less governs two separate areas called the Wa State within the Shan State of Myanmar, one bordering Thailand in southern Shan State and another bordering China in northeast Shan State. [Source: Wikipedia]

In China, the Wa mainly live in the mountain and hills areas of Cangyuan, Ximeng, Lancang, Menglian, Shuangjiang, Genma, Yongde, Zhenkang counties in southwestern Yunnan in A Wa Shan ( "Awa mountain area" between the Lancangjiang (Mekong River) and the Sa'erwenjiang (Salween River) in the south of the Nushan mountain chain. Cangyuan and Ximeng have the largest concentrations of Wa. About 50 percent of the total Wa population in China lives there. The Wa generally live together with the Hans, Dais, Blangs, De'angs, Lisus, and Lahus. [Source: Liu Jun, Museum of Nationalities, Central University for Nationalities, Science of China, China virtual museums, Computer Network Information Center of Chinese Academy of Sciences ~]

Ximeng and Cangyuan counties are the center the A Wa Shan,. The percentage of the Wa there was population was 88.3 in 1958 and 79 by 1978. In the six counties where they are found they live among peoples (mostly Dai, Lahu, and Han) and the percentage of the Wa population runs from 9 to 20. Wa can also be found in the Baoshan, Dehong, and Xishuangbanna areas of Yunnan. Ximeng, Cangyuan, Menglian and Langcang are situated in undulating mountain ridges some 2,000 meters above sea level. the region has a subtropical climate, okay soil and plentiful rainfall suitable for growing dry rice, paddy rice, maize, millet, buckwheat, potatoes, cotton, hemp, tobacco and sugarcane, as well as such subtropical fruits as bananas, pineapples, mangoes, papayas and oranges. [Source: china.org]

The Wa are the 26th largest ethnic group and the 25th largest minority out of 55 in China. They numbered 429,709 and made up 0.03 percent of the total population of China in 2010 according to the 2010 Chinese census. Wa populations in China in the past: 396,709 in 2000 according to the 2000 Chinese census; 351,974 in 1990 according to the 1990 Chinese census. A total of 286,158 were counted in China in 1953; 175,000 were counted in 1958; 200,272 were counted in 1964; 266,853 were counted in 1978 and 271,050 were, in 1982. [Sources: People’s Republic of China censuses, Wikipedia]

Origin of the Wa

Cangyuan, a Wa area in Yunnan in China

Much of what is known about Wa history has been determined from Wa oral histories and Chinese historical records. Based on Wa legends, scholars think that the Wa originated in the mountains where they now reside. Chinese historical records from 109 B.C. refer to tribes believed to be the ancestors of the Wa. Records from the Tang dynasty (618-907) refer to the Wa themselves. [Source: Wang Aihe,“Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 6: Russia-Eurasia/China” edited by Paul Friedrich and Norma Diamond, 1994]

There are several different legends about the origin of the Wa. According to the most common one the ancestors of the Wa came out from "Sigang Li", meaning they came out of a gourd or a cave in the mountain ( "Sigang" means a gourd or a cave in the mountain and "Li" means "to come out"). It is said that the gourd and the cave are in north Myanmar, not far from Simeng and Cangyuan Counties. God created Daguya and Yeli, who were the first ancestors of the Wa people; Daneng smeared his saliva on Yenumu, who later gave birth to the first Wa generation. [Source: chinatravel.com +++]

The Wa people are believed to be descendants of the "Baipu" people who according to Chinese historical records lived before the Qin period (221 BC- 26 BC). They were called "Wangman", "Guci" and "Kawa" in the Tang, Ming and Qing Dynasties respectively. Wa people in different places in Yunnan Province call themselves by different names. For example, those living in Ximeng, Menglian and Lancang Counties call themselves "Ah Wa" or "Le Wa"; those in Cangyuan, Shuangjiang and Gengma Counties call themselves "Ba Raoke" or "Bu Rao"; and those living in Yongde and Zhenkang Counties call themselves "Wa". Interestingly, these names all mean "the people living on the mountain." +++

Wa History

From the 11th century onward the Wa were ruled successively by the Dali Kingdom, Nazhhao Kingdom. and the Chinese Yuan, Ming and Qing Dynasties. The Wa established their homeland in the Wa Shan region and unified in part due to encroachment from the Han Chinese and other groups Feared as ferocious fighters, the Wa intimidated the British colonials, the Shan, the Chinese, other ethnic groups in Myanmar, drug lords and even Myanmar generals. The Wa were hired as mercenaries and fighters by the Koumingtan in the early 1950s and later by the Beijing-backed Communist Party of Burma.

According to the Chinese government: Between the Tang and Ming dynasties, the Wa mainly engaged in hunting, fruit collecting and livestock breeding. After the Ming Dynasty, agriculture became their main occupation, and they passed out of the primitive clan communes into village communes. However, development in various areas was not balanced. Over a long time in the past, the Vas living with the Hans, Dais and Lahus had had their culture and economy develop faster through interchanges. As a whole, however, development of the Va society was rather slow before liberation. This was due mainly to long-term oppression by reactionary ruling classes and imperialist aggression. There were three areas in terms of social development: The Ava mountainous area with Ximeng as the center and including part of Lancang and Menglian counties, inhabited by one-third of the total Va population. There, private ownership had been established, but with the remnant of a primitive communal system still existing. The area on the edges of Ava Moutnain, covering Cangyuan, Gengma and Shuangjiang counties and part of Lancang and Menglian counties, and the Va area in the Xishuangbanna Dai Autonomous Prefecture, where two-thirds of the Va people live. There, the economy already bore feudal manorial characteristics. In some areas in Yongde, Zhenkang and Fengqing, where a few Vas live with other ethnic peoples, the Va economy had developed into the stage of feudal landlord economy. [Source: china.org]

The Wa have traditionally had reputation for violence. Until after World War II, the area where they lived in Burma was avoid by British colonial officials, who referred to the Wa as “wild” and avoided any contact with them because of their practice of headhunting. During the colonial period, the area inhabited by Wa became a major source of opium; production of the narcotic markedly increased after Myanmar gained independence in 1949. [Source: Encyclopedia Britannica]

Cangyuan Cliff Painting

Cangyuan cliff paintings

The Cangyuan cliff paintings, said to have been produced by the ancestors of the Wa, are located mainly in the valleys of the Mengdonghe River among Ruliang Mountain, Bamboo Mountain and Gongnong Mountain in Congyuan county of Yunnan Province. Since 1962, eleven painting spots have been discovered in Menglai, Dinglai, Mankan, Heping, Mangyang, Mengxing in the mid-northern Cangyuan County. Most of them were painted on pieces of vertical cliffs tens of meters above the ground. [Source: Liu Jun, Museum of Nationalities, Central University for Nationalities ~]

The main subjects of the cliff paintings are: human images, animal images, pictures of village, and pictures of hunting, offering sacrifice and dancing. The style is simple and unsophisticated and the images provide clues to the lifestyle of people that created them. The human body is expressed by triangles without facial features, but the limbs were painted with different postures, often expressing movement and action. Activities such as dancing can be figured out from the different postures of the limbs. Animals have vague body and head features but their identify can be determined by things like the shape and size of horns, tails, feet and ears. Most of the paintings are reddish brown in color. The pigments of the painting are a mix of red iron ore, shellac and blood of animals. According to preliminary study and analysis of experts, oldest works date back to Neolithic Stone Age, and are more than 3000 years old. ~

See XISHUANGBANNA, SOUTHERN YUNNAN, THE MEKONG IN CHINA AND THE DAI AND WA Separate Article factsanddetails.com

Development of the Wa Under the Communists in China

According to the Chinese government: “In December 1949, the Wa, together with other ethnic groups in Yunnan Province, were liberated. In 1951, the central government sent a delegation to the Ava mountainous areas to help the Va people solve urgent problems in production and daily life, and to settle disputes among tribes. The Menglian Dai-Lahu-Va Autonomous County was set up in 1954 and the Cangyuan Va Autonomous County in 1955. They were followed by the founding of Ximeng Va Autonomous County in 1964 and the Cangyuan Va Autonomous County in 1965. In the course of practicing regional autonomy, many Va cadres were trained, paving the way for implementing the Communist Party's united front policy, for further winning over and uniting with the patriots from the upper strata of the Vas, and for carrying out social reform in Va areas. [Source: china.org.cn]

“Different steps and methods were adopted by the government in social reform, taking the unbalanced socio-economic development in various areas into consideration. In Zhenkang and Yongde the Vas, together with local Hans, carried out land reform and abolished the system of feudal exploitation and oppression. Then they carried out socialist reform in agriculture. In most of the areas in Ximeng, Cangyuan, Shuangjiang, Gengma and Menglian, exploiting and primitive backward elements were reformed in gradual steps through mutual aid and cooperation, with government support, so as to pass into socialism.

“Two important economic measures were taken in the Va areas to improve production and people's life. One was to provide the poor Va peasants with food and seeds, draught cattle and farm tools, while helping them build irrigation projects to extend rice paddy fields. The other was to set up more state trading organizations to expand state trade. These measures brought changes to local production and daily life, enabling the people to do away with usury and exploitation by landlords. Through transforming mountains, harnessing rivers and extending paddy fields, the Va people in the Ximeng area changed their primitive cultivation methods.

urbaniized Wa

“In pre-liberation days, eight out of 10 Va people were half-starved. For several months in a year they had to eat wild vegetables and wild starchy tubers. Their ordinary meal was thick gruel cooked with vegetables. However, by 1981 they owned 1,600 hectares of paddy fields, achieving good yields. In some fields the output per hectare came to 7.5 tons. Industry was unheard of in the Ava mountainous areas in the past. Now there are hydro-power stations, tractor stations and locally-run workshops producing and repairing farm tools, smelting iron and processing food. The first generation of workers has come into being.

“Industrial and agricultural development brought marked changes to the commerce, transport and communications, culture and education and health of the Va people. A case in point is Yanshi Village in Cangyuan County. There wasn't a presentable house except those owned by the village head. Now it has grown into a rising township, with a bank, a health center, primary and middle schools, a farm tool plant and tailors' shops as well as many stores. The village has become an economic and cultural center.

“Many new schools have been set up in the Va areas. Nine out of 10 Va children are at school. Cultural centers, film projection teams and bookstores broaden the knowledge of the Va people and enrich their life. Every county in the Ava mountainous area has hospitals. Over the past 30 years and more a new atmosphere of unity has prevailed in the Va areas. The old enmities, resulting from abduction of oxen and headhunting, have been replaced by mutual help in production and construction through mediation. Clan warfare which was common in pre-liberation days, seldom takes place.”

Wa State in Myanmar

The Wa have carved out a virtual independent nation for itself in eastern Myanmar called the Wa State and have the largest nonstate army in Asia. For centuries, they resisted rule by outsiders, including the Chinese and the British, and and have continued to do so against the Myanmar government, whether it be democratically elected or a military junta. As of the early 2020s, when the as Myanmar's military government was fighting a brutal civil war and waging brutal campaigns against a number of armed ethnic and Burman opponents, the Wa were relatively secure in the rugged hills bordering China, expanding their influence over Shan State, Myanmar's biggest region, largely financed with money from the drug trade.. Wa State has been headed since 1995 by Bao Youxiang, chairman of the ruling United Wa State Party (UWSP) and a veteran of guerrilla warfare and opium smuggling. [Source: Denis D. Gray, Nikkei, August 12, 2022]

The Wa State embraces an area of about 35,000 square kilometers, roughly equal to the size of the Netherlands. The Wa population in the two areas of Wa State are estimated to be 400,000 to 500,000. Wa State is an autonomous self-governing polity. It has its own political system, administrative divisions and army. However, the Wa State government recognises Myanmar's sovereignty over all of its territory, and the Burmese government does not consider Wa State's political institutions to be legitimate. The 2008 Constitution of Myanmar officially recognises the northern part of Wa State as the Wa Self-Administered Division of Shan State. The Wa State is a a one-party socialist state ruled by UWSP, which split from the Communist Party of Burma (CPB) in 1989, Wa State is divided into three counties, two special districts, and one economic development zone. The administrative capital is Pangkham, formerly known as Pangsang. [Source: Wikipedia]

See Separate Article WA STATE AND THE UNITED WA STATE ARMY factsanddetails.com

Wa Language and Names

Wa knot manuscript

The Wa language belongs to the Wa-Deang branch of the Mon-Khmer group of the Austro-Asiatic language family. This is different from most other southern Chinese ethnic groups, which speak language that belong to the Tibeto-Burman branch of the Sino-Tibetan family of languages. The Wa language is very close to De'ang (spoken by the De'ang or Palaungs, who reside in Yunnan, China and in Myanmar) and Bulang (spoken by the Bulang or Blang, who reside in Yunnan, China). The Wa language is divided into three or four dialects, which include "Baraoke", "Awa" and "Wa". The Wa language is closely related to the language of the Dai ethnic group, from which 10 percent of the Wa words are borrowed.

The Wa people previously had no written language. They kept records and accounts by woodcutting, bean counting, rope knotting, and engraving bamboo strips. Each strip ranged from half an inch to an inch in width. They passed messages by using material objects. For example, sugarcane, bananas and salt signified friendship, chilies meant anger, cock feathers denoted urgency and gunpowder and bullets indicated the intention of clan warfare. [Source: china.org.cn]

The first written language created for the Wa was developed by British missionaries for the purpose of propagating Christianity and was not widely used. In the 1950s, after the People’s Republic of China was founded, the Chinese government a created new written language for the Wa that was not utilized much either. Many in China Wa speak Chinese and use the written Chinese language. [Source: chinatravel.com +++]

The Wa have employed a naming system in which father's and son's names are linked. This system has traditionally appeared at the transition period from matrilineal clan system to patrilineal clan system.

Wa Religion

Many Wa still embrace their traditional animist religion. In China, the Wa used to have a reputation for being deeply religious feeling. Research in the 1950s found that 30 percent of Wa wealth was spent on for religious activities and 60 days a year was devoted to the worship of their gods. Even stomach aches and skin itching were believed to be caused by gods. [Source: Ethnic China *]

The Wa people view themselves as the caretakers of the world, because they were the first people on Earth. Animist Wa believe that things like weather and disease are caused by natural spirits of the water, trees, mountains. Ancestor worship is practiced. Wa believe that the deceased become spirits that can bring bad fortune or good fortune depending on how they are treated. Villages usually have a religious expert called a moba who presides over rituals and takes care of healing. Traditionally festivals and events like weddings, births and funerals have been marked with animal sacrifices and chicken bone divinations.

A few Wa are Buddhists or Christians. In Cangyuan and Shuangjiang counties, Wa influenced by the Dais, have embraced Theravada Buddhism. Christianity spread into some areas mainly as the result of the efforts of European missionaries. Wa dead have traditionally been buried inside the village near the family house or outside in the common cemetery of the clan or village in coffins made from a hollowed tree split down the middle. They are buried with a piece of silver or coins and tools and other objects which the Wa believe can be taken to the afterlife.

Wa Traditional Religion

The Wa have traditionally believed that each object or natural phenomena has its own spirit and that people, through rituals and ceremonies, can summon these spirits for their own benefit. They also believe that the different illnesses are caused by different gods, spirits and demons that can be appeased with different ceremonies. When they buy horses or cows, they conduct special ceremonies;. If they don’t do this, the Wa believe, the soul of the animal will not come with them, but will remain with the previous owner. *\

The Wa have traditionally believed that each object or natural phenomena has its own spirit and that people, through rituals and ceremonies, can summon these spirits for their own benefit. They also believe that the different illnesses are caused by different gods, spirits and demons that can be appeased with different ceremonies. When they buy horses or cows, they conduct special ceremonies;. If they don’t do this, the Wa believe, the soul of the animal will not come with them, but will remain with the previous owner. *\

The supreme Wa god is Mujij, whose five children created the heaven, the earth, lightning, earthquakes and the Wa. Other important Wa gods are: Agu, the God of the Water; Dawu, God of the Wind; and Dawa, God of the Trees. Sacrifices have traditionally been a big part of Wa religious life. It has been argued that one reason for this has been that agricultural productivity and natural disasters were common and sacrifices were done in hopes of securing good luck to boost harvest and ward off disasters. *\

The Wa believe that all mountains, rivers and other natural phenomena have own their deities. They associate ghosts, gods and spirits with their ancestors. They call the sun god "Li", the moon god "Lun", plant god "Pen", animal god "Neng", air god "Nu" and water god "Ah-yong". The Wa people think that ghosts, gods and spirits, big or small, should have their own duties and responsibilities and can't manage others' business. If something unfortunate happens to a person, he has to give offerings to a particular ghost or god in charge of it for blessings. [Source: chinatravel.com +++]

The Wa believe that people die because their ancestors call their soul. After death, a shaman is summoned to teach to the soul the route to their ancestors land. The soul, the Wa believe, needs a few days to slowly abandon the body. Dor that reason they fed the corpse with a straw placed in the mouth for a few days. A place is left for the dead in the family house in case the dead wants to come back to visit. *\

Wa Sacred Forest and Baptism Myth

Many ethnic groups in southwest China and Southeast Asia maintain sacred forests near their villages. These forests are usually have a deep meaning to the life of the village and its inhabitants. These forests have traditionally been protected by taboos, such as not cutting the trees, not allowing domestic animals inside, forbidding pollution from human or animal urine or excrements and prohibiting jokes and outsiders. [Source: Ethnic China *]

Among the Wa sacred forests are treated in different ways depending on the place they inhabit. In places where the head hunting activities were once practiced, they were considered place were the deities of the village resided. Among the Wa of Ximeng, in the past, village often had several sacred forests: some for different clans, some for different functions, such as expelling the devils or disposing of hunted heads.

One part of the Wa creation myth has similarities with the baptism of Jesus in the Jordan River. story in the Bible. According to a Wa myth, as related by Wei Deming, many, many years ago, when the human beings took their first steps on the earth, the were like fetuses that never grew up even when they got old. These fetus-people could not talk, could not see, and could not hear. One day, Yenamu, one of the female ancestors of the Wa, lead the people to a river, where they bathed and washed their heads. After that the people opened their eyes to see, and their ears to hear and their souls awoke. This myth also shows the importance of heads to the Wa and explains why they hunted heads and expressed affection to lovers by combing their hair. [Source: Wei Deming. “Wa zu wenhua shi” (“History of the Culture of the Wa”). Yunnan minzu chubanshi. Yunnan Nationalities Press, *]

Wa Head Hunting and Sacrifices

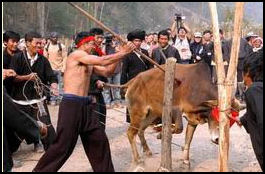

Sacrifice

Headhunting was associated with magical rites performed to ensure the fertility of the land. Heads taken either from outsiders or enemy villages were given as a sacrifice to the grain spirit. There were special ceremonies for offering the head to the grain god, which was typically kept in an agricultural field. Then there was another ritual performed when the head was moved to where heads from past rituals were kept (See Rituals Below). [Source: Wikipedia]

Traditional villages had shrines where a buffalo was sacrificed once every year at a special Y-shaped post. Blood, meat and skin were given as offerings and then divided up among village members. Animals have also been traditionally sacrificed at celebrations such as marriages and funerary rituals among the traditional spirit-worshiping Wa,. Rhese practices still endure among Christian Wa. However, Buddhist Wa have different traditions.

Lafou was the god of head hunting. There are several myths that offer different explanations and stories behind the origin of headhunting but all of them consider the activity as an offering to the gods. Headhunting is believed to have ceased completely in the Chinese part of the Wa region when the Communists came to power in 1949, but was still practiced by some groups in Myanmar after that. News of head hunting raids appeared in the newspapers into the 1960s and headhunting is thought to have continued into the 1970s. Now only chickens, pigs and cows are sacrificed. The human sacrifices have been replaced by the cow sacrifice. The most important Wa ceremonies are those that involve the worship of sacred drums. [Source: Ethnic China *]

Heads were kept in the “Wooden Drum House” before being placed on a stake with other heads captured in previous years. Villages hung human head every year to ensure a good harvest. The head of a bearded man was considered the ultimate sacrificial offering. Wa shamans believed the growth of a beard would greatly increase crop yields. Among the Wa of Ximeng, in the past, some sacred forests were reserved for the disposal of hunted heads. These sacred forests were considered the home of the great god Muyiji and was regarded as highly sacred. In the past, the Wa performed special ceremonies after a head was taken. Before the ceremony the head was kept for a year in the House of the Drum. Afterwards the head was disposed of in a sacred forest, usually inside a bamboo basket, a hollow trunk or in a stone.

During the headhunting ceremony the head was placed on a bamboo stake was about two meters high and 30-40 centimeters of diameter. When it was disposed of in the sacred forest ot was often placed in a hollowed wooden trunk and covered with a stone. Sometimes a face was carved on the outer surface of the trunk, signaling there was a head inside. Near these trunks were usually stones carried there for the sacrifice a female pig, conducted when the head was moved to the forest. The heads sometimes were placed on a round stone with the skull placed in a concave part of the upper surface of the stone

Wa Ceremonies, Sacrifices and Headhunting Rituals

The Wa have traditionally used their own calendar with a new year that begins in December and four main annual celebrations: 1) the service to the water spirit in New Years Day, in which many animals are sacrificed and new bamboo water piper are built for drinking water; 2) the “dragging the wooden drum,” in which a big tree is cut in the first and dragged to the village to make a drum; 3) the hunting of a human head to appease the grain god; and 4) the sacrifice of four oxen to transport the spirit of the head to the forest. The Wa are famous for their wooden drum dance Wa girls do a “hair-swaying dance. During the oxen sacrifices villages slice of pieces of meat from dozens of living oxen. These customs were banned in the 1950s by the Chinese government. Some have been revived in recent years but due to the loss of many moba in the Cultural Revolution the revival has been spotty.

Wang Aihe wrote in the “Encyclopedia of World Cultures”: The Wa conducted sacrificial rituals and chicken-bone divinations for family or individual affairs such as sickness, birth, building houses, weddings or funeras. At the beginning their year (December in the Western calendar), they used to conduct the service to the water spirit, in which the whole village sacrificed animals and built a new bamboo water pipe for drinking water. [Source: Wang Aihe, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 6: Russia-Eurasia/China” edited by Paul Friedrich and Norma Diamond, 1994 |~|]

Wa Sacrifice Posts

The "dragging the wooden drum" was a ten-day-long ritual in which all the men of the village cut a big tree from the forest and made a huge drum out of it. This drum was used for important rituals and emergency military actions. The headhunting ritual was sacrifice to the grain spirit. The head came from either from outsiders or enemy villages. The purpose of the oxen sacrifices was to transport the previous year's head from the "Wooden Drum House," where it had been kept, to the "spirits forest" outside of the village, where all the previous heads were put on top of wooden stakes, which stood together as a wood. Called "cutting the tail of the oxen," this ritual lasted seventeen days, during which time the whole village raced to tear the flesh off from a dozen to dozens of live oxen, one after another, with knives. In addition to the headhunting that has been prohibited since the 1950s, all the other rituals were also prohibited as "superstitions" during the Cultural Revolution in the 1960s and 1970s. In the 1980s, some of the rituals and divinations were revived, but since many old moba died during the Cultural Revolution without bringing up a younger generation, much tradition was lost and revived rituals are fairly different from the old ones, having lost a lot of old practices, functions, and interpretations, and having added new ones of their own. |~|

Wa Festivals

The Sowing Seeds Festival is held in the "Qiai" month of the Wa calendar, that is, March of the solar calendar. In this festival, the Wa people gather to sacrifice an ox. The event is usually hosted by the owner of the ox. After the owner butchers the ox by thrusting an iron sword into its heart, its flesh is divided evenly into many parts, which are used by the villagers as offerings to worship their ancestors. The bones of the ox, symbolizing wealth, belong to its owner. After worshipping their ancestors and having lunch, the Wa people begin to sow rice seeds. [Source: chinatravel.com +++]

The "Bengnanni" Festival, the equivalent of Wa New Year, is held on the last day in the last month of the Wa calendar. It is a time to bid farewell to the past and welcome new arrivals. Before dawn, all the young and middle-aged men gather in the house of the village headman, with a pig and a cock killed as sacrificial offerings. Each family, holding a basin of glutinous rice and a piece of baba (rice cake) on a bamboo table, pays a New Year call to the headman and worship ghosts, gods and their ancestors. After that, all the Wa people give babas to one another, greeting with words of blessings. At dawn, after presenting offerings to their sacred tree, the Wa people go hunting and fishing, praying for good luck in the new year. +++

The Wa celebrate a torch festival in which participants light torches in front of their houses and set large fires in their village squares. The festival honors a woman who leaped into a fire rather make love with a king. Before the village torch is lit people gather around it and drink rice wine.

The so-called "pulling the wooden drum" is an activity in which Wa villagers go the forest and cut a tree trunk for a drum, pull it into the village and make a drum with it to replace the old drum. It is usually held in the eleventh Chinese lunar month (the first month in Wa calendar), which is equivalent to December of the solar calendar. The time of the pulling wooden drum is decided in the meeting of leaders of the village and the main sacrifice offerer (the person who bears the cost of the activity and the cattle sacrificed). Often several water buffalo, oxen or cattle are sacrificed and butchered.

See See Pulling the Drum Under WA PEOPLE LIFE AND SOCIETY factsanddetails.com

New Rice Festival

The New Rice Festival is the Wa’s grandest festival. Celebrating the harvest and the taste new rice, it is held at different times in different places because the rice if ready for harvesting at different times due to different climate. Different villages or even households often hold it at different times however it is usually celebrated in the seventh or eighth lunar month of the Chinese calendar (the ninth or tenth month in Wa calendar). The date is determined according to the maturity situation of grain or the day corresponding to one of the 12 symbolic animals of an elder who has recently died. The purpose of the festival is to invite ghosts of ancestors to return home, taste the new rice with family members, and enjoy good times together. Families ask their ancestors' souls in heaven to protect their descendants, bring the family happiness and deliver good weather for the crops. So that the Wa in different places could celebrate the "New Rice Festival" together, in 1991, Cangyuan Wa Autonomous County and Ximeng Wa Autonomous County decided together to fix the date of the "New Rice Festival" to the 14th day of the Wa’s eighth lunar month. [Source: Liu Jun, Museum of Nationalities, Central University for Nationalities, Science of China, China virtual museums, Computer Network Information Center of Chinese Academy of Sciences]

The New Rice Festival usually lasts three days. In the middle of the eighth month of the lunar calendar when paddies are just ripe, all the Wa families go to the paddy fields to pick some fresh paddies at the time announced by the village headman. When returning home, they put some paddies in the prepared barn or bamboo basket, and pound the rest to be husked rice grains, which are soon cooked. After that, they place seven bowls of rice with meat and seven bowls of wine as offerings on the table, inviting the spirits of their ancestors and the gods in charge of the heaven, earth, mountains, and grains to enjoy their harvests. Then they burn seven pieces of incense. At the end of the rite, all the family members eat the seven bowls of rice. In the evening, Most of the people gather to enjoy the festival, singing and dancing until dawn. On the second day, all the young people go out to repair the old roads and bridges or build new ones, making ready for carrying bags of fresh paddies into the village. On the third day, the Wa people, continue to enjoy the festival with more singing and dancing. The young men and women often take this opportunity to seek out a mate. [Source: chinatravel.com +++]

Often Wa families celebrates the New Rice Festival independently. They make their own wine and prepare meat and delicacies are prepared. A branch of grain is hung on the door welcome the spirit of the dead back home. A shaman chants special words while the rice is offered to gods and ancestors. After the ceremony is finished, members of the family taste the new rice starting with the shaman and the old. Then the host opens the door to tell neighbors the news that they are celebrating the festival, and people come to congratulate him with all kinds of presents. The host butcher a chicken, pig or even cattle to entertain guests. Everyone celebrates the happiness of good harvest with joyous songs. ~

Image Sources: Nolls China website, Joho maps

Text Sources: 1) “Encyclopedia of World Cultures: Russia and Eurasia/ China”, edited by Paul Friedrich and Norma Diamond (C.K.Hall & Company, 1994); 2) Liu Jun, Museum of Nationalities, Central University for Nationalities, Science of China, China virtual museums, Computer Network Information Center of Chinese Academy of Sciences, kepu.net.cn ~; 3) Ethnic China *\; 4) Chinatravel.com; 5) China.org, the Chinese government news site china.org | New York Times, Lonely Planet Guides, Library of Congress, Chinese government, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, Wikipedia, BBC, CNN, and various books, websites and other publications.

Last updated September 2022