AYMAN RAI AL-ZAWAHIRI

Dr. Ayman Rabi al-Zawahiri Dr. Ayman Rabi al-Zawahiri is an Egyptian doctor and the current leader of Al-Qaida. He was the head of Islamic Jihad in Egypt, which merged with Al-Qaida in 1998, and was involved in assassination of Egyptian President Anwar Sadat. Zawahiri helped Osama bin Laden found Al-Qaida in 1988 and was widely viewed as bin Ladens’s right hand from their years together in Afghanistan and Sudan up until bin Laden’s death in 2011. Zawahiri is well educated and comes from a religious-intellectual family. In the minds of some he has was the real brains behind Al-Qaida while bin Laden was its mascot and spiritual leader.

Al-Zawahiri is a surgeon by training. Born into an upper middle class family of doctors and scholars, he was brought up in Maadi, a fashionable neighborhood in Cairo. His father was a pharmacology professor. One grandfather was the grand imam of Al-Azhar University, Sunni Islam's supreme seat of learning. The other grandfather was a university president. An uncle was leading figure in the Arab League.

Al-Qaida expert Peter Bergen wrote in Time: “Zawahiri, a cerebral Egyptian surgeon who joined his first jihadist cell at age 15, is as much the force behind al-Qaeda as his more famous friend Osama bin Laden. When the two first met in Pakistan in 1986, al-Zawahiri made a powerful impression on the younger, inexperienced Saudi millionaire. Within a couple of years, bin Laden was funding al-Zawahiri's militant group Al Jihad, while Egyptian militants close to al-Zawahiri were helping bin Laden found al-Qaeda. [Source: Peter Bergen, Time, April 30, 2006]

Zawahri's whereabouts is unknown, although he has long been thought to be hiding in Pakistan somewhere in that country’s tribal belt near the border of Afghanistan. Washington is offering a $25 million reward for any information leading to his capture or conviction. He may be dead.

See Separate Article AYMAN RAI AL-ZAWAHIRI AND AL-QAIDA factsanddetails.com

Zawahiri’s Family

Al-Azhar Mosque Lawrence Wright wrote in The New Yorker: Five miles south of the chaos of Cairo is a quiet middle-class suburb called Maadi. A consortium of Egyptian Jewish financiers, intending to create a kind of English village amid the mango and guava plantations and Bedouin settlements on the eastern bank of the Nile, began selling lots in the first decade of the twentieth century...The center of this cosmopolitan community was the Maadi Sporting Club. Founded at a time when Egypt was occupied by the British, the club was unusual for admitting not only Jews but Egyptians. Community business was often conducted on the all-sand eighteen-hole golf course, with the Giza Pyramids and the palmy Nile as a backdrop. [Source: Lawrence Wright, The New Yorker, September 16, 2002]

“In 1960, Dr. Rabie al-Zawahiri and his wife, Umayma, moved from Heliopolis to Maadi. Rabie and Umayma belonged to two of the most prominent families in Egypt. The Zawahiri (pronounced za-wah-iri) clan was creating a medical dynasty. Rabie was a professor of pharmacology at Ain Shams University, in Cairo. His brother was a highly regarded dermatologist and an expert on venereal diseases. The tradition they established continued into the next generation; a 1995 obituary in a Cairo newspaper for one of their relatives, Kashif al-Zawahiri, mentioned forty-six members of the family, thirty-one of whom were doctors or chemists or pharmacists; among the others were an ambassador, a judge, and a member of parliament.

“The Zawahiri name, however, was associated above all with religion. In 1929, Rabie's uncle Mohammed al-Ahmadi al-Zawahiri became the Grand Imam of Al-Azhar, the thousand-year-old university in the heart of Old Cairo, which is still the center of Islamic learning in the Middle East. The leader of that institution enjoys a kind of papal status in the Muslim world, and Imam Mohammed is still remembered as one of the university's great modernizers. Rabie's father and grandfather were Al-Azhar scholars as well.

Umayma Azzam, Rabie's wife, was from a clan that was equally distinguished but wealthier and also a little notorious. Her father, Dr. Abd al-Wahab Azzam, was the president of Cairo University and the founder and director of King Saud University, in Riyadh. He had also served at various times as the Egyptian ambassador to Pakistan, Yemen, and Saudi Arabia. His uncle was a founding secretary-general of the Arab League. "From the first parliament, more than a hundred and fifty years ago, there have been Azzams in government," Umayma's uncle Mahfouz Azzam, who is an attorney in Maadi, told me. "And we were always in the opposition." At seventy-five, Mahfouz remains politically active: he is the vice-president of the religiously oriented Labor Party. He was a fervent Egyptian nationalist in his youth. "I was in prison when I was fifteen years old," he said proudly. "They condemned me for making what they called a 'coup d'état.' " The memory brought an ironic smile to his face. In 1945, Mahfouz was arrested again, in a roundup of militants after the assassination of Prime Minister Ahmad Mahir. "I myself was going to do what Ayman has done," he said.

Zawahiri’s Early Family Life

Maadi neighborhood of Cairo Lawrence Wright wrote in The New Yorker: “At a time when public displays of religious zeal were rare — and in Maadi almost unheard of — the couple was religious but not overtly pious. Umayma went about unveiled. There were more churches than mosques in the neighborhood, and a thriving synagogue. Children quickly filled the Zawahiri home. The first, Ayman and a twin sister, Umnya, were born on June 19, 1951. [Source: Lawrence Wright, The New Yorker, September 16, 2002]

“Obese, bald, and slightly cross-eyed, Rabie al-Zawahiri had a reputation as a devoted and slightly distracted academic, beloved by his students and by the neighborhood children. "He knew only his laboratory," Mahfouz Azzam told me. Zawahiri's research occasionally took him to Czechoslovakia, at a time when few Egyptians travelled, because of currency restrictions. He always returned laden with toys for the children. He sometimes found time to take them to the movies...In the summer, the family went to a beach in Alexandria. Life on a professor's salary was constricted, especially with five ambitious children to educate. The Zawahiris never owned a car until Ayman was out of medical school. Omar Azzam remembers that Professor Zawahiri kept hens behind the house for fresh eggs and that he liked to distribute oranges to his children and their friends. "Everyone was astonished," Omar said. " 'Why all these oranges?' He'd say, 'They're better than vitamin-C tablets.' He was a pharmacology expert, but he was opposed to chemicals."

"The whole activity of Maadi revolved around the Maadi Sporting Club," Samir Raafat, the historian of the suburb, told me one afternoon as he drove me around the neighborhood. "If you were not a member, why even live in Maadi?" The Zawahiris never joined, which meant, in Raafat's opinion, that Ayman would always be curtained off from the center of power and status. "He wasn't mainstream Maadi; he was totally marginal Maadi," Raafat said. "The Zawahiris were a conservative family. You would never see them in the club, holding hands, playing bridge. We called them saidis. Literally, the word refers to someone from a district in Upper Egypt, but we use it to mean something like 'hick.' "

Ayman Rabi al-Zawahiri’s Early Life

Horse in Maadi Lawrence Wright wrote in The New Yorker: “Ayman and a twin sister, Umnya, were born on June 19, 1951. The twins were extremely bright, and were at the top of their classes all the way through medical school. A younger sister, Heba, also became a doctor. The two other children, Mohammed and Hussein, trained as architects...Omar Azzam, the son of Mahfouz and Ayman's second cousin, says that Ayman enjoyed cartoons and Disney movies, which played three nights a week on an outdoor screen. [Source: Lawrence Wright, The New Yorker, September 16, 2002]

“At one end of Maadi is Victoria College, a private preparatory school built by the British. During the nineteen-sixties, it was one of the finest schools in the country, and English was still the language of instruction...Zawahiri, however, attended the state secondary school, a modest low-slung building behind a green gate, on the opposite side of the suburb. "It was the hoodlum school, the other end of the social spectrum," Raafat told me. The educational standards were far below those of Victoria College. "The two schools never even played sports against each other," he said. "One was very Westernized, the other had a very limited view of the world. A lot of people will tell you that Ayman was a vulnerable young man. He grew up in a very traditional home, but the area he lived in was a cosmopolitan, secular environment. You have to blend in or totally retrench."

“Ayman's childhood pictures show him with a round face, a wary gaze, and a flat and unsmiling mouth. He was a bookworm and hated contact sports — he thought they were "inhumane," according to his uncle Mahfouz. From an early age, he was devout, and he often attended prayers at the Hussein Sidki Mosque, an unimposing annex of a large apartment building; the mosque was named after a famous actor who renounced his profession because it was ungodly. No doubt Ayman's interest in religion seemed natural in a family with so many distinguished religious scholars, but it added to his image of being soft and otherworldly.”

“Although Ayman was an excellent student, he often seemed to be daydreaming in class. "He was a mysterious character, closed and introverted," Zaki Mohamed Zaki, a Cairo journalist who was a classmate of his, told me. "He was extremely intelligent, and all the teachers respected him. He had a very systematic way of thinking, like that of an older guy. He could understand in five minutes what it would take other students an hour to understand. I would call him a genius."

“Once, to the family's surprise, Ayman skipped a test, and the principal sent a note to his father. The next morning, Professor Zawahiri met with the principal and told him, "From now on, you will have the honor of being the headmaster of Ayman al-Zawahiri. In the future, you will be proud." Indeed, that incident was never repeated. "He was perfect in everything," Ayman's cousin Omar told me. "In his last year in school, his twin sister used to study so much, but Ayman was not doing the same. One of our cousins said, 'You will see the result. Ayman will get better grades than she.' And it happened."

“Ayman often showed a playful side at home. "When he laughed, he would shake all over — yanni, it was from the heart," Mahfouz says. But at school he held himself apart. "There were a lot of activities in the high school, but he wanted to remain isolated," Zaki told me. "It was as if mingling with the other boys would get him too distracted. When he saw us playing rough, he'd walk away. I felt he had a big puzzle inside him—something he wanted to protect."

Zawahiri Becomes a Jihadist

Muslim Brotherhood Emblem When he was 15 Al-Zawahiri formed a jihadist cell made up of high school students who opposed the Egyptian government. He continued his militant activities while earning his medical degree, later merging his cell with other militants to form Islamic Jihad. In the 1970s, Al-Zawahiri organized demonstrations at his medical school demanding separate classes for men and women.With Egyptian Islamic Jihad he organized and armed cells opposed to the government of Anwar al-Sadat. "We were a group of students from Maadi High School and other schools," Zawahiri said of his days as a young radical, when he was put on trial for conspiring in the assassination of Sadat in 1981.

Lawrence Wright wrote in The New Yorker: “The members of his cell usually met in one another's homes; sometimes they got together at a mosque and then went to a park or to a quiet spot on the tree-lined Corniche along the Nile. In the beginning, there were five members, and before long Zawahiri became the emir, or leader. "Our means didn't match our aspirations," he conceded in his testimony. But he never seemed to question his decision to become a revolutionary. "Bin Laden had a turning point in his life," Omar Azzam points out, "but Ayman and his brother Mohammed were like people in school moving naturally from one grade to another. You cannot say those boys were naughty guys or playboys, then turned one hundred and eighty degrees. To be honest, if Ayman and Mohammed repeated their lives, they would live them the same way." [Source:Lawrence Wright, The New Yorker, September 16, 2002]

“Under the monarchy, before Nasser's assumption of power, the affluent residents of Maadi had been insulated from the whims of the government. In revolutionary Egypt, they suddenly found themselves vulnerable. "The kids noticed that their parents were frightened and afraid of expressing their opinions," Zawahiri's former schoolmate Zaki told me. "It was a climate that encouraged underground work." Clandestine groups like Zawahiri's were forming all over Egypt. Made up mainly of restless or alienated students, they were small and disorganized and largely unaware of each other. Then came the 1967 war with Israel. The speed and the decisiveness of Israel's victory in the Six-Day War humiliated Muslims who had believed that God favored their cause. They lost not only their armies and territory but also faith in their leaders, in their countries, and in themselves. For many Muslims, it was as though they had been defeated by a force far larger than the tiny country of Israel, by something unfathomable — modernity itself. A newly strident voice was heard in the mosques, one that answered despair with a simple formulation: Islam is the solution.

“The clandestine Islamist groups were galvanized by the war, and, as Nasser had feared, their primary target was his own, secular regime. In the terminology of jihad, the priority was to defeat the "near enemy" — that is, impure Muslim society. The "distant enemy" — the West — could wait until Islam had reformed itself. For the Islamists, this meant, at a minimum, imposing Sharia on the Egyptian legal system. Zawahiri also wanted to restore the caliphate, the rule of Islamic clerics, which had formally ended in 1924, after the dissolution of the Ottoman Empire, but which had not exercised real power since the thirteenth century. Once the caliphate was reëstablished, Zawahiri believed, Egypt would become a rallying point for the rest of the Islamic world. He later wrote, "Then, history would make a new turn, God willing, in the opposite direction against the empire of the United States and the world's Jewish government."

Zawahiri and Sayyib Qutb

Sayyib Qutb Al-Zawahiri was greatly influenced by Sayyib Qutb, an Egyptian writer most active in the 1960s who insisted there that jihad be conducted offensively against the enemies of Islam. Qutb argued that Muslim governments that did not implement true sharia law were fair game for such offensives and wanted secular Middle Eastern governments excommunicated from the Muslim community. That process of declaring other Muslims to be apostates, an idea promoted by Qutb, is known as takfir. It would become a key al Qaeda doctrine.

"Qutb was the most prominent theoretician of the fundamentalist movements," Zawahiri later wrote in a brief memoir entitled "Knights Under the Prophet's Banner," which first appeared in serial form, in the London-based Arabic newspaper Al-Sharq al-Awsat, in December, 2001. "Qutb said, 'Brother push ahead, for your path is soaked in blood. Do not turn your head right or left but look only up to Heaven.' " [Source: Lawrence Wright, The New Yorker, September 16, 2002]

Lawrence Wright wrote in The New Yorker: “Ayman al-Zawahiri heard again and again about the greatness of Qutb's character and the terrible things he endured in prison. The effect of these stories can be gauged by an incident that took place one day in the mid-sixties, when Ayman and his admiring younger brother Mohammed were walking home from the mosque after dawn prayers. Hussein al-Shaffei, the Vice-President of Egypt and one of the judges in the 1954 roundup of Islamists, "offered to give them a ride," Omar Azzam recalls. "We would all have been proud to have the Vice-President give us a ride — even to be in a car! But Ayman and Mohammed refused. They said, 'We don't want to get this ride from a man who participated in the courts that killed Muslims.' "

"The Nasserite regime thought that the Islamic movement received a deadly blow with the execution of Sayyid Qutb and his comrades," Zawahiri wrote in his memoir. "But the apparent surface calm concealed an immediate interaction with Sayyid Qutb's ideas and the formation of the nucleus of the modern Islamic jihad movement in Egypt." The same year Qutb was hanged, Zawahiri helped form an underground militant cell dedicated to replacing the secular Egyptian government with an Islamic one. He was fifteen years old.

Zawahiri as a Revolutionary Medical Student in the Early Sadat Years

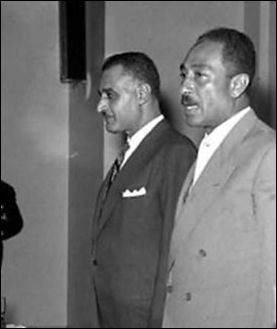

Nasser and Sadat Lawrence Wright wrote in The New Yorker: Nasser died of a heart attack in 1970. His successor, Sadat, desperately needed to establish his political legitimacy, and he quickly set about trying to make peace with the Islamists. Saad Eddin Ibrahim, a dissident sociologist at the American University in Cairo and an advocate of democratic reforms, who was recently sentenced to seven years in prison, told me last spring, "Sadat was looking around for allies. He remembers the Muslim Brothers. Where are they? In prison. He offers the Brothers a deal: in return for their political support, he'll allow them to preach and to advocate, as long as they don't use violence. What Sadat didn't know is that the Islamists were split. Some of them had been inspired by Qutb. The younger, more radical ones thought that the older ones had gone soft." Sadat emptied the prisons, without realizing the danger that the Islamists posed to his regime.The Muslim Brothers, who were forbidden to act as a genuine political party, began colonizing professional and student unions. By 1973, a new band of young fundamentalists had appeared on campuses, first in the southern part of the country, then in Cairo. They called themselves Al-Gama'a al-Islamiyya — the Islamic Group. Encouraged by Sadat's acquiescent government, which covertly provided them with arms so that they could defend themselves against any attacks by Marxists and Nasserites, the Islamic Group, which was uncompromising in its militancy, radicalized most of Egypt's universities. Soon it became fashionable for male students to grow beards and for female students to wear the veil. [Source: Lawrence Wright, The New Yorker, September 16, 2002]

“Zawahiri claimed that by 1974 his group had grown to forty members. In April of that year, another group of young Islamist activists seized weapons from the arsenal of a military school, with the intention of marching on the Arab Socialist Union, where Sadat was preparing to address the nation's leaders. The attempted coup d'état was very much along the lines of what Zawahiri had been advocating: rather than revolution, he favored a sudden, surgical military action, which would be far less bloody. The coup was put down, but only after a shootout that left eleven dead.

Eventually, in the late seventies, the various underground groups began to discover each other. Four of these cells, including Zawahiri's, merged to form Egyptian Islamic Jihad. Their leader was a young man named Kamal Habib. Like Zawahiri, Habib, who had graduated in 1979 from Cairo University's Faculty for Economics and Political Science, was the kind of driven intellectual who might have been expected to become a leader of the country but turned violently against the status quo. Arrested in 1981 on charges related to the assassination of Sadat, he was released from prison after serving a ten-year sentence. In Cairo earlier this year, Habib told me, "Most of our generation belonged to the middle or the upper-middle class. As children, we were expected to advance in conventional society, but we didn't do what our parents dreamed for us. And this is still a puzzling issue for us. For example, Ayman finished his degree as a doctor, specializing in surgery, and set up a clinic in a duplex apartment that he shared with his parents in Maadi. Anybody else would have been happy with this. But Ayman was not happy, and this led him into trouble."

Zawahiri graduated from medical school in 1974, then spent three years as a surgeon in the Egyptian Army, posted at a base outside Cairo. In February, 1978, he married Azza Nowair, the daughter of a prominent Cairo family, at the Continental-Savoy Hotel, which had slipped from colonial grandeur into dowdy respectability. According to the wishes of the bride and groom, there was no music, and photographs were forbidden. "It was pseudo-traditional," Schleifer recalls. "Lots of cups of coffee and no one cracking jokes."

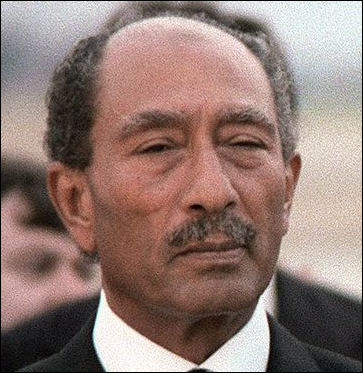

Zawahiri and the Assassination of Sadat

Sadat Zawahiri was outraged by Sadat’s signing of the 1979 peace treaty with Israel and clamp down on Islamists, that included a ban on the niqab at universities, that followed the rise of Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini in Iran. Lawrence Wright wrote in The New Yorker: “Zawahiri envisioned not merely the removal of the head of state but a complete overthrow of the existing order. Stealthily, he had been recruiting officers from the Egyptian military, waiting for the moment when Islamic Jihad had accumulated enough strength in men and weapons to act. His chief strategist was Aboud al-Zumar, a colonel in the intelligence branch of the Egyptian Army and a military hero of the 1973 war with Israel. Zumar's plan was to kill the most powerful leaders of the country and capture the headquarters of the Army and the state security, the telephone-exchange building, and the radio-and-television building. From there, news of the Islamic revolution would be broadcast, unleashing — he expected — a popular uprising against secular authority all over the country. It was, Zawahiri later testified, "an elaborate artistic plan." [Source: Lawrence Wright, The New Yorker, September 16, 2002]

“One of the members of Zawahiri's cell was a daring tank commander named Isam al-Qamari. Zawahiri, in his memoir, characterizes Qamari as "a noble person in the true sense of the word. . . . Most of the sufferings and sacrifices that he endured willingly and calmly were the result of his honorable character." Although Zawahiri was the senior member of the Maadi cell, he often deferred to Qamari, who had a natural sense of command — a quality that Zawahiri notably lacked. "Qamari saw that something was missing in Ayman," said Yasser al-Sirri, an alleged member of Jihad — he denies any affiliation with the group — who took refuge in London after receiving a death sentence in Egypt. "He told Ayman, 'No matter what group you belong to, you cannot be its leader.' "

“According to Zawahiri's memoir, Qamari began smuggling weapons and ammunition from Army strongholds and storing them in Zawahiri's medical clinic in Maadi. In February of 1981, as the weapons were being transferred from the clinic to a warehouse, police arrested a man carrying a bag loaded with guns, along with maps that showed the location of all the tank emplacements in Cairo. Qamari, realizing that he would soon be implicated, dropped out of sight, but several of his officers were arrested. Zawahiri inexplicably stayed put. The evidence gathered in these arrests alerted government officials to a new threat from the Islamist underground. That September, Sadat ordered a roundup of more than fifteen hundred people, including many prominent Egyptians — not only Islamists but also intellectuals with no religious leanings, Marxists, Coptic Christians, student leaders, and various journalists and writers. The dragnet missed Zawahiri but captured most of the other Islamic Jihad leaders.

“However, a military cell within the scattered ranks of Jihad had already set in motion a hastily conceived plan: a young Army recruit, Lieutenant Khaled Islambouli, had offered to kill Sadat during an appearance at a military parade. Zawahiri later testified that he did not learn of the plan until nine o'clock on the morning of October 6, 1981, a few hours before it was scheduled to be carried out. One of the members of his cell, a pharmacist, brought him the news at his clinic. "In fact, I was astonished and shaken," Zawahiri told interrogators. In his opinion, the action had not been properly thought through. The pharmacist proposed that they do something to help the plan succeed. "But I told him, 'What can we do?' " Zawahiri told the interrogators. He said that he felt it was hopeless to try to aid the conspirators. "Do they want us to shoot up the streets and let the police detain us? We are not going to do anything." Zawahiri went back to his patient. When he learned, a few hours later, that the military exhibition was still in progress, he assumed that the operation had failed and that everyone connected with it had been arrested.

“The parade commemorated the eighth anniversary of the 1973 war. Surrounded by dignitaries, including several American diplomats, President Sadat was saluting the troops when a military vehicle veered toward the reviewing stand. Lieutenant Islambouli and three other conspirators leaped out and tossed grenades into the stand. "I have killed the Pharaoh!" Islambouli cried, after emptying the cartridge of his machine gun into the President, who stood defiantly at attention until his body was riddled with bullets.

Arrest and Trial of Zawahiri

Underground prison cell in

Egyptian SS headquarters Lawrence Wright wrote in The New Yorker: “It is still unclear why Zawahiri did not leave Egypt when the new government, headed by Hosni Mubarak, rounded up seven hundred suspected conspirators. In any event, at the end of October Zawahiri packed his belongings for another trip to Pakistan. He went to the house of some relatives to say goodbye. His brother Hussein was driving him to the airport when the police stopped them on the Nile Corniche. "They took Ayman to the Maadi police station, and he was surrounded by guards," Omar Azzam told me. "The chief of police slapped him in the face — and Ayman slapped him back!" Omar and his father, Mahfouz, recall this incident with amazement, not only because of the recklessness of Zawahiri's response but also because until that moment they had never seen him resort to violence. After his arrest and imprisonment, Zawahiri became known as the man who struck back. [Source: Lawrence Wright, The New Yorker, September 16, 2002]

“Under interrogation, Zawahiri admitted that "Dr. Isam" was actually Qamari, and he also confirmed that Qamari had supplied him with weapons. Qamari was still unaware that Zawahiri was in custody when he called the Zawahiri home and made a date for the two of them to meet at the Zawya Mosque in Embaba. The police arrested Qamari when he arrived at the mosque. In Zawahiri's memoir, the closest he comes to confessing this betrayal is an oblique reference to the "humiliation" of imprisonment: "The toughest thing about captivity is forcing the mujahid, under the force of torture, to confess about his colleagues, to destroy his movement with his own hands, and offer his and his colleagues' secrets to the enemy." Qamari was given a ten-year sentence. "He received the news with his unique calmness and self-composure," Zawahiri recalls. "He even tried to comfort me, and said, 'I pity you for the burdens you will have to carry.' " Perversely, after Zawahiri testified against Qamari and thirteen others, the authorities placed the two of them in the same cell. Qamari was later killed in a shootout with the police after escaping from prison.

“Zawahiri was defendant No. 113 of more than three hundred militants accused of aiding in the assassination of Sadat, and of various other crimes as well — in Zawahiri's case, possession of a gun. Nearly every notable Islamist in Egypt was implicated in the plot. (Zawahiri's brother Mohammed was sentenced in absentia, but the charges were later dropped. The youngest brother, Hussein, spent thirteen months in prison before the charges against him were dropped. Lieutenant Islambouli and twenty-three others were tried separately, and five of them, including Islambouli, were executed.)”

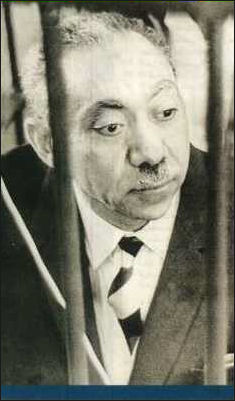

Zawahiri Rails Against Jews and Americans From His Prison Cage

Lawrence Wright wrote in The New Yorker: “The defendants, some of whom were adolescents, were kept in a zoolike cage that ran across one side of a vast improvised courtroom set up in the Exhibition Grounds in Cairo, where fairs and conventions are often held. International news organizations covered the trial, and Zawahiri, who had the best command of English among the defendants, was designated as their spokesman. [Source: Lawrence Wright, The New Yorker, September 16, 2002]

“Video footage that was shot during the opening day of the trial, December 4, 1982, shows the three hundred defendants, illuminated by the lights of TV cameras, chanting, praying, and calling out desperately to family members. Finally, the camera settles on Zawahiri, who stands apart from the chaos with a look of solemn, focussed intensity. Thirty-one years old, he is wearing a white robe and has a gray scarf thrown over his shoulder. At a signal, the other prisoners fall silent, and Zawahiri cries out, "Now we want to speak to the whole world! Who are we? Who are we? Why they bring us here, and what we want to say? About the first question, we are Muslims! We are Muslims who believe in their religion! We are Muslims who believe in their religion, both in ideology and practice, and hence we tried our best to establish an Islamic state and an Islamic society!" The other defendants chant, in Arabic, "There is no god but God!"

Zawahiri continues, in a fiercely repetitive cadence, "We are not sorry, we are not sorry for what we have done for our religion, and we have sacrificed, and we stand ready to make more sacrifices!"... The others shout, "There is no god but God!"... Zawahiri continues,"We are here — the real Islamic front and the real Islamic opposition against Zionism, Communism, and imperialism!" He pauses, then: "And now, as an answer to the second question, Why did they bring us here? They bring us here for two reasons! First, they are trying to abolish the outstanding Islamic movement . . . and, secondly, to complete the conspiracy of evacuating the area in preparation for the Zionist infiltration."...The others cry out, "We will not sacrifice the blood of the Muslims for the Americans and the Jews!"

“The prisoners pull off their shoes and raise their robes to expose the marks of torture. Zawahiri talks about the torture that took place in the "dirty Egyptian jails . . . where we suffered the severest inhuman treatment. There they kicked us, they beat us, they whipped us with electric cables, they shocked us with electricity! They shocked us with electricity! And they used the wild dogs! And they used the wild dogs! And they hung us over the edges of the doors" — here he bends over to demonstrate — "with our hands tied at the back! They arrested the wives, the mothers, the fathers, the sisters, and the sons!"...The defendants chant, "The army of Muhammad will return, and we will defeat the Jews!"... The camera captures one particularly wild-eyed defendant in a green caftan as he extends his arms through the bars of the cage, screams, and then faints into the arms of a fellow-prisoner. Zawahiri calls out the names of several prisoners who, he says, died as a result of torture. "So where is democracy?" he shouts. "Where is freedom? Where is human rights? Where is justice? Where is justice? We will never forget! We will never forget!"

Zawahiri Tortured in Prison

Montasser al-Zayat, an Islamist attorney who was imprisoned with Zawahiri, told The New Yorker; "When the security forces brought people here, they took off their clothes, handcuffed them, blindfolded them, then started beating them with sticks and slapping them on the face..."Ayman was beaten all the time — every day...They sensed that he had a lot of significant information." Zayat wrote a damning biography of his former friend and colleague, "Ayman al-Zawahiri as I Knew Him," whose publications was stopped by pressure from Zawahiri's supporters. For years, he has been the main source for information about Zawahiri and the Islamist movement in Egypt. "I didn't know him before we were brought here, but we were able to talk through a hole between our cells," Zayat said. "We discussed why the operations failed. He told me that he hadn't wanted the assassination to take place. He thought they should have waited and plucked the regime from the roots through a military coup. He was not that bloodthirsty." [Source: Lawrence Wright, The New Yorker, September 16, 2002]

Lawrence Wright wrote in The New Yorker: Zayat, among other witnesses, maintains that the traumatic experiences suffered by Zawahiri during his three years in prison transformed him from a relative moderate in the Islamist underground into a violent extremist. They point to what happened to his relationship with Isam al-Qamari, who had been his close friend and a man he greatly admired. Immediately after Zawahiri's arrest, officials in the Interior Ministry began grilling him about Qamari's whereabouts. In their relentless search for Qamari, they threw the Zawahiri family out of their house, then tore up the floors and pulled down the wallpaper looking for evidence. They also waited by the phone to see if Qamari would call. "They waited for two weeks," Omar Azzam told me. Finally, a call came. The caller identified himself as "Dr. Isam," and asked to meet Zawahiri. A police officer, pretending to be a family member, told "Dr. Isam" that Zawahiri was not there. According to Azzam, the caller suggested, " 'Have Ayman pray the magreb' "the sunset prayer" 'with me.' And he named a mosque where they should meet."

“The head of the Interior Ministry's anti-terrorism unit at the time, Fouad Allam, supervised the hunt for Qamari” and “interrogated almost every major Islamic radical since 1965, when he interrogated Sayyid Qutb. I asked Allam about Zawahiri's manner when he talked to him. "Shy and distant," he said. "He didn't look at you when he talked, which is a sign of politeness in the Arab world." Allam maintains that none of the prisoners were tortured. "It's all a legend," he told me — one designed to discredit the regime and enhance the standing of the Islamists. But Kamal Habib, who spent ten years in Egyptian prisons, and whose hands are spotted with scars from cigarette burns, maintains that Zawahiri's tales of torture are true. "The higher you were in the organization, the more you were tortured," he told me. "Ayman knew a number of the military officers who were directly involved in the assassination. He was subjected to severe torture."

“Zawahiri later testified in a case brought by former prisoners against the intelligence unit that conducted the prison interrogations. His allegations of torture were substantiated by forensic medical reports, which noted evidence of six injuries from assaults with "a solid instrument." He was also supported by the testimony of one of the intelligence officers, who said that he had seen Zawahiri, "his head shaved, his dignity completely humiliated, undergoing all sorts of torture." The officer went on to say that he had been in the interrogation room when another prisoner was brought in. The officers demanded that Zawahiri confess to complicity in the assassination plot in front of his fellow-conspirator. When the prisoner said, "How can you expect him to confess when he knows that the penalty is death?" Zawahiri reportedly replied, "The death penalty is more merciful than torture."

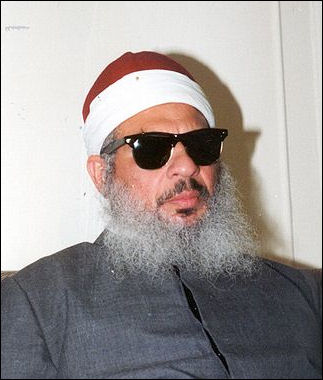

Zawahiri, Islamic Jihad and Sheikh Omar Abdel Rahman

Omar Abdel-Rahman Al-Zawahiri was a founder and head of Islamic Jihad in Egypt. The group came together in the late seventies, when he various underground groups began to discover each other, and four of these cells, including the one Zawahiri founded when he was 15, merged to form Egyptian Islamic Jihad. Their first leader was a young man named Kamal Habib. Islamic Jihad opposed to the government of Anwar al-Sadat and was aware of the plot to assassinate Sadat but was not directly involved it.

The goal of Islamic Jihad was to overthrow the civil government of Egypt and impose a theocracy that might eventually become a model for the entire Arab world. In an anti-terrorism speech, U.S. president George Bush even mentioned the group by name Two other high ranking Al-Qaida members: Fahmi Nasr (a.k.a. Mohammed Salah) and Tariq Anwar were leaders of Egyptian Islamic Jihad. But at the time Zawahiri was in prison in Cairo, years of guerrilla warfare had left the group shattered and bankrupt.

Lawrence Wright wrote in The New Yorker: While Zawahiri was in prison, he came face to face with Egypt's best-known Islamist, Sheikh Omar Abdel Rahman, who had also been charged as a conspirator in the assassination of Sadat. A strange and forceful man, blinded by diabetes in childhood and blessed with a stirring, resonant voice, Rahman had risen in Islamist circles because of his eloquent denunciations of Nasser. After Nasser's death, Rahman's influence grew, especially in Upper Egypt, where he taught theology at the Asyut branch of Al-Azhar University and developed a loyal following among Islamist students. [Source: Lawrence Wright, The New Yorker, September 16, 2002]

Rahman “became a spiritual adviser to Al-Gama'a al-Islamiyya, the Islamic Group, which was then on its way to becoming the largest student association in the country. Some of the young Islamists were financing their activism by shaking down shopkeepers and small-business owners, many of whom were Christians. The theology of jihad requires a fatwa — a religious ruling — to justify actions that would otherwise be considered criminal. Sheikh Omar obligingly issued fatwas that allowed attacks on Christians and the plunder of jewelry stores, on the justification that a state of war existed between Christians and Muslims.

“Although the members of the two leading militant organizations, the Islamic Group and Islamic Jihad, shared the common goal of bringing down the Sadat government, they differed sharply in their ideology and their tactics. Sheikh Rahman preached that all humanity could embrace Islam, and he was happy to spread this message. Zawahiri profoundly disagreed. Distrustful of the masses and contemptuous of any faith other than his own stark version of Islam, he preferred to act secretly and unilaterally, until the moment his group could seize power and impose its totalitarian religious vision.

In the Cairo prison, members of the two groups had heated debates about the best way to achieve a true Islamic revolution, and they quarrelled endlessly over who was the best man to lead it. In one argument, according to Montasser al-Zayat, Zawahiri pointed out that Sharia states that the emir cannot be blind. Rahman countered that Sharia also decrees that a prisoner cannot be emir. The rivalry between the two men became extreme. Zayat claims that he tried to persuade Zawahiri to moderate his attacks on Rahman, but Zawahiri refused to back down.

Radicalized Zawahiri Released from Prison in 1984

Lawrence Wright wrote in The New Yorker: “Zawahiri was released in 1984, a hardened radical. Saad Eddin Ibrahim, the American University sociologist, spoke with Zawahiri after his release, and noted that he may have had an overwhelming desire for revenge. "Torture does have that effect on people," he told me. "Many who turn fanatic have suffered harsh treatment in prison. It also makes them extremely suspicious." Torture had other, unanticipated effects on these extremely religious men. Many of them said that after being tortured they had had visions of being welcomed by saints into Paradise and of the just Islamic society that had been made possible by their martyrdom. [Source: Lawrence Wright, The New Yorker, September 16, 2002]

“Ibrahim had done a study of political prisoners in Egypt in the nineteen-seventies. According to his research, most of the Islamist recruits were young men from villages who had come to one of the cities for schooling. The majority were the sons of middle-level government bureaucrats. They were ambitious and tended to be drawn to the fields of science and engineering, which accept only the most qualified students. They were not the alienated, marginalized youth that a sociologist might have expected. Instead, Ibrahim wrote, they were "model young Egyptians." Ibrahim attributed the recruiting success of the militant Islamist groups to their emphasis on brotherhood, sharing, and spiritual support, which provided a "soft landing" for the rural migrants to the city. Zawahiri, who had read the study in prison, disagreed, Ibrahim told me. In their conversation, Zawahiri said to him, "You have trivialized our movement by your mundane analysis. May God have mercy on you."

“Zawahiri decided to leave Egypt, worried, perhaps, about the political consequences of his testimony in the case against the intelligence unit. According to his sister Heba, who is a professor of oncology at the National Cancer Institute at Cairo University, he thought of applying for a surgery fellowship in England. Instead, he arranged to work at a medical clinic in Jidda, Saudi Arabia. At the Cairo airport, he ran into his friend Abdallah Schleifer. "Where are you going?" Schleifer asked. "Saudi," said Zawahiri, who appeared relaxed and happy. The two men embraced. "Listen, Ayman," Schleifer said. "Stay out of politics." "I will," Zawahiri replied. "I will!"

“Zawahiri arrived in Jidda in 1985. At thirty-four, he was a formidable figure. He had been a committed revolutionary and a member of an Islamist underground cell for more than half his life. His political skills had been honed by prison debates, and he had discovered in himself a capacity — and a hunger — for leadership. He was pious, determined, and embittered.”

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, The Guardian, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, AFP, Wall Street Journal, The Atlantic Monthly, The Economist, Global Viewpoint (Christian Science Monitor), Foreign Policy, Wikipedia, BBC, CNN, NBC News, Fox News and various books and other publications.

Last updated July 2012