ECONOMICS IN THE DEVELOPING WORLD

Tailor in Chad On average, each citizen in western Europe, the United States and Japan consumers 32 times more resources such as fossil fuels than people in the developing world.

Economic problems in the developing world include corruption, poor infrastructure, lack of skilled labor, political instability, weak protection of intellectual rights, and the possibility of contacts being canceled on a whim.

Relatively few people have reaped the rewards of economic prosperity. Many villagers have been left behind. Some peasant have actually been made worse off by environmental damages caused by unbridled growth.

Many villagers are ill-equipped to deal with the modern economic world. One small factory owner told Arthur Zich of National Geographic, "Farmers find it hard to survive in an industrialized society. Farmer want to work in the factories, but transition is difficult and few of them adjust. They have no skills. They lack education. They lack the attitude one needs to learn. They have no sense of time, of living by the clock."

In his book “The Fortune at the Bottom of the Pyramid”, C. K. Prahalad says that the poorest two thirds of the world’s population have $5 trillion in purchasing power.

Economic History in the Developing World

Sachs wrote: “The failure of the Third World to grow as rapidly as the First World is the result of a complex mix of factors, some geographical, some historical and some political. Imperial rule...left the conquered regions bereft of education, health care indigenous political leadership and adequate physical infrastructure.”

“Often, newly independent countries in the post-World War II period made disastrous political choices such as socialist economic models or a drive for self-sufficiency behind inefficient trade barriers. But perhaps most pertinent today, many regions that have been left further behind have faced special obstacles and hardships: diseases such as malaria, drought-prone climates in locations not suitable for irrigation, extreme isolation in mountains and landlocked regions, an absence of energy resources such as coal, gas and oil and other liabilities that have kept these areas outside the mainstream of global economic growth.”

The economies grew slowly after World War II.. There was little foreign investment. The gap between the rich and poor grew. There were large numbers of unemployed and under employed. In the countryside, peasants remained under the control of landowners.

With independence, governments controlled much of the revenues sources such as oil and local merchants obtained a lager percentage of the import-export trade. Large land owners were able to continue controlling much of the land. and were able to make handsome profits selling raw materials to Western countries.

In the 1960s and 70s, developing countries promoted self-reliance and regarded foreign investment as a form of imperialism and multinational corporations and as agents of evil.

The boom in the 1990s left many developing nations, about 25 of them in Africa, worse off. Foreign aid declined, debts increased, AIDS-HIV rates soared and the prices of important commodities dropped.

Developing countries suffered greatly as a result of economic crisis in 2008 and 2009 even though they had nothing to do with starting it. They suffered as demand for their exports dried up, investors didn’t want to invest, loan money dried up, and developing countries were more reluctant to provide aid.

Antole Kaletsky wrote in the Times of London, “Consumers in countries such as China, India, Brazil and Indonesia have been far less affected by the financial crisis. In fact consumer credit and mortgage markets in these countries are just beginning to develop, creating the conditions for powerful growth in consumer demand.”

See Colonialism, History

Emerging Economies Faring Better in Economic Downturn

Market in BamakoHenry Chu wrote in the Los Angeles Times in August 2011, “Look at the state of the economy from anywhere in America or Europe these days and all is gloomy: Governments deep in debt. Consumers reluctant to spend. Businesses afraid to hire. But gaze out from the vantage of some of the world's emerging economies and the picture gets brighter. Although few will pretend that their fates are immune to the ripples of a globalized economy, new players such as China, Brazil and India see their rising prosperity as less dependent on the credit cards of Western consumers. Their governments are also less burdened by debt, and they retain confidence that better days lie ahead.[Source: Henry Chu, Los Angeles Times, August 21, 2011]

Globalization means that people and economies are connected more than ever, but it doesn't necessarily mean that everyone swims or sinks together. The most dispiriting news these days comes out of the developed nations of the West. In the United States, the mix of high government debt, hostility to stimulus spending and diving consumer confidence raises fear that the country is entering an extended period of stagnation. Across the Atlantic, debt levels have spooked bond markets, forced humiliating bailouts and led to brutal cuts that call the European welfare state into question.

Across emerging economies, there is the feeling that a corner has been turned. In Asia, the demons of the 1998 financial crisis are being exorcised. From the cocky entrepreneurs of New Delhi to the Turkish businessmen fanning out across the Middle East and Central Asia, this time their fate seems to lie in their own hands.

Brazil is now an agricultural superpower and natural-resources giant, shipping vast quantities of commodities to China, the world's workshop. Both countries' domestic consumption levels are rising, enticing foreign investors, including Western companies, in search of opportunities no longer available at home. Their governments have more flexibility to act, unburdened by crippling debt levels.

Foreign Investment in the Developing World

In January 2011, Reuters reported, “Developing countries and economies in transition together attracted more foreign investment than developed countries in 2010 for the first time, a United Nations study showed. The report by the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) was further evidence that economic recovery is more robust in developing than in rich countries. Overall, flows of foreign direct investment (FDI) stagnated at almost $1.12 trillion in 2010 after $1.14 billion in 2009, but are still 25 percent below pre-crisis levels in 2005-2007, UNCTAD said in its latest global investment trends monitor. [Source: Jonathan Lynn, Reuters, January 17, 2011]

Foreign investors seek out countries with cheap labor, good basic infrastructure such as roads and airports, reliable sources of electricity and energy, trainable workforce and stable political conditions. The companies they invest in learn to operate under conditions with currency swings, buying local materials when the currency is weak, then stockpiling them to use when the currency recovers.

Foreign investors in developing countries have helped contribute to a rising standard of living for some even though their primary goal is to make profits not to improve the living standards of their workers. As workers skills improve, their wages rise and they begin to buy consumer goods for themselves. A middle class is generated.

More than $422 billion was invested in developing countries between 1988 and 1995. Much of the money was invested in Asia. Large parts of Africa and Latin America has been bypassed. Even though poverty worldwide has decreased slightly in recent years, it has increased slightly in the Caribbean, Latin America and sub-Sahara Africa.

Capital flight — the sudden flow of hard currency out of a country, particularly when economic problems crop up — is a serious problem in some developing countries.

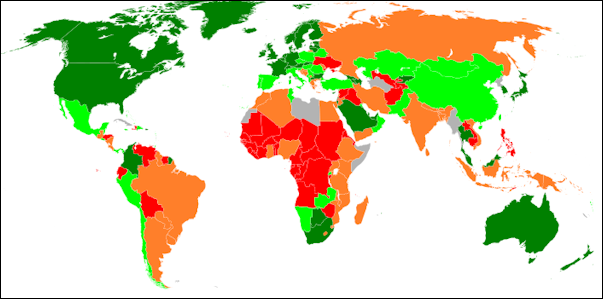

Ease of Doing Business Index in 2010

Foreign Companies in the Developing World

Nike, MTV, Disney and McDonald’s, are as well-known in the developing world as they are in the developed world. Shops in remote villages that often don't have milk, cheese, or butter always seem to have plenty of Coca-Cola, Pepsi and Orange Crush plus calenders and posters produced by these companies. Coke or Pepsi truck are sometimes among the few vehicles you see on the roads in remote areas. In some mountainous areas you see people carry basketfuls of Coke and Pepsi bottles on their backs on footpaths and trails.

McDonald’s, Kentucky Fried Chicken and Pizza Hut are franchises that are locally owned. Coke, Fanta and Pepsi are made by local bottlers. They provide badly needed jobs for the people and taxes for the government.

Unilever has been very successful marketing products like shampoo in small packets in the developing world. Nestle sells instant milk and baby formula.

General Electric is aiming to become a one-stop general store for developing world infrastructure, offering a wide range of things including jet engines, health care equipment, turbines, rail products, water oil and gas equipment, and even financial services. G.E. is taking this route in part because it sees more growth potential in the developing world than it does in the developed world and aims to create good relations with the countries it does business with by employing local people by doing things like shipping parts for locomotives and having them assembled locally.

Shoe manufacturers and textiles makers that rely on cheap labor are among the first industries to arrive. They mainly produce goods to be exported back to the country where the company is from or for the world market. These companies raise wages and living standards. While they have been accused of exploiting labor and damaging the environment in the United States and Europe they are welcome in emerging economies as engines for growth.

A study of Oxfam found that multinational retailers and grocery chains in their quest for ever lower prices for customers are driving down wages and lengthening work hours for millions of workers, the vast majority of them women.

Debt and Debt Relief in the Developing World

During the 1970s and 80, often with encouragement from the developed countries, developing countries borrowed large sums of money and incurred huge debts, in many cases going further in the hole as they took out more loans to meet their interest payments.

Poor countries often owe banks, governments and business in advanced countries billions of dollars. The debts are so large that the governments of these countries often pay more on the interest payments on these debts than they do for education, health care and infrastructure projects combined. Peasant farmers have been kicked off their land so that cash crops can be grown for export to earn money to pay off government debts.

Economist Jeffrey Sachs wrote in the New York Times, "About 700 million people — the very poorest — are held in debt bondage by the rich countries. The co-called Highly Indebted Poor Countries are a group of 42 financially bankrupt and destitute economies. They owe $100 billion in unpayable debt to the World Bank, the International Monetary Fund, development banks and governments, often reflecting the failures of past development loans...Many of those loans were made to tyrannical regimes to suit Cold War aims. Many simply reflect misguided ideas of the past."

Debt relief — simply wiping these debts off the books and excusing the debtor nations of paying them — is a major issue. Among those who have spoken out on the issue are Bono of U2. The debts for some countries have been relieved Not everyone thinks that debt relief is the answer. On the issue Deutsche Bank economist Norbery Walter said, "Opening agricultural markets in Europe and the United States may have provide more real help to these states."

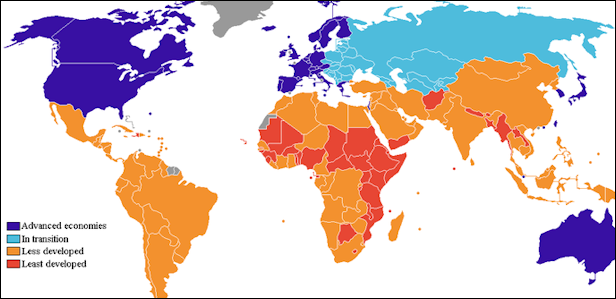

Developed and developing countries

Emerging Country Debt Attracting Investors

December 2011, AFP reported: “The bonds of emerging countries, which have been following sounder policies than the United States and eurozone, are attracting investors seeking to diversify risks as well as earn high returns. Today emerging markets represent 10-15 percent of the global debt market, up from six percent in 2000, and even big money managers such as PIMCO and BNY Mellon in the United States, or Swiss private bank Pictet have jumped into the game. [Source: Sophie Deviller, Agence France Presse, December 4, 2011]

"Since the summer and the United States lost its triple-A rating" from Standard & Poor's "there has been a very marked interest in this category of assets," said Herve Thiard, director of Pictet Paris. "At more than six percent on average, the return on emerging country debt is very attractive in dollars as well as local currencies -- it is more than three times that on US Treasury bonds" that are currently yielding around two percent, explained Brigitte Le Bris, head of fixed-income investment at Natixis Asset Management.

Brazilian bonds denominated in reals bring in returns of over 12 percent per year currently. Another plus, the fundamentals of these countries are generally more solid than for the United States or the eurozone, which the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development said is entering a slight recession.

In a major role-reversal, emerging countries have now started lecturing advanced countries about the need to balance budgets. "The weak growth and deep deficits in developed countries drove the need for a geographical diversification in favor of countries with growth and ... sound public finances," said bond specialist Ernesto Bettoni at BNP Paribas bank.

The International Monetary Fund says that emerging countries have on average public debts equivalent to 40 percent of gross domestic product compared to 90 percent for rich countries. That debt divergence is expected to widen further through 2015, noted Didier Lambert, a bond manager at JP Morgan Asset Management. Certain countries have been able to keep their debt level very low, such as Russia at 11.2 percent of GDP, thanks to its oil windfall.

While ratings agencies have been repeatedly downgrading their ratings of southern European countries and the top triple-A ratings eurozone countries are under threat, they have raised their ratings for emerging markets Last month, Standard & Poor's raised Brazil's rating one notch to BBB, citing in particular the ability of its economy to withstand the slowdown in the global economy. Since last year Thailand, Malaysia, the Philippines and Indonesia have also had their ratings upgraded.

"These countries are now better armed to battle against a crisis scenario," observed Le Bris."Inflationary pressures have been contained in most of the countries, except in Turkey or South Africa. Since 2008 central banks have raised rates and their currencies have appreciated, currency reserves have grown, budgets are globally in balance," she noted. "All these elements help them to better resist external shocks," said Le Bris.

Finally, emerging country bond markets have more players, which makes trading fluid, with local investors such as pension funds, insurance companies and central banks increasingly active.Bonds in local currencies are becoming accessible for foreign investors, such as in Mexico, Brazil and Colombia. China has yet to open up yuan-denominated debt to foreign investors, but is slowly opening up its currency. Since 2010 it has allowed foreign companies to issue debt in yuan. Well aware of heightened investor interest, leaders of the Group of 20 top economies have called on emerging markets to develop their local currency bond markets.

Resources in the Developing World

Resources were originally heralded as a great blessing and source of income. But they have turned out to be a curse. They encourage people to sit around and do nothing while money flows in with little effort and discourages them from developing a work ethic, entrepreneurship and manufacturing which all help an economy grow. A study of 97 developing countries by economists Jeffrey Sachs and Andrew Warner found that the more a country relied on natural resources the lower its rate of growth was.

The fate of many resources-rich countries is that a handful of politicians and well-connected businessmen become rich while the masses remain poor.

See Curse of Oil Wealth Under OIL PRICES, THE CURSE OF OIL WEALTH, WOMEN'S RIGHTS AND WAR factsanddetails.com

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, Yomiuri Shimbun, The Guardian, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated January 2012